Scientists Open a Massive Cave in the Appalachians – And Turn Pale When They Meet a Hidden Bigfoot Tribe

The drill screamed into the mountain until, suddenly, it didn’t.

Three hundred feet down into solid Appalachian limestone, the massive bit had chewed through rock like it was born for nothing else. Then, in an instant, it dropped into nothing—spinning freely in empty space. The rig shuddered, then went still.

On the ridgeline, where a cold October wind knifed across the bare ground, the entire team fell silent.

Dr. Elias Thorne lifted his hand and cut the motor. The abrupt quiet felt deafening after the metallic roar, and for a heartbeat there was nothing but the wind and the faint ticking of cooling machinery.

They had found it.

After eighteen months of ground‑penetrating radar surveys, seismic mapping, grant writing, and bureaucratic battles with the National Park Service, the “anomaly” they had been chasing was no longer just lines on a screen.

Beneath the mountains of eastern Kentucky, the void was real.

Thorne, a paleoanthropologist whose career was built on fossils and fragments, not living mysteries, stared at the narrow bore hole in the rock. His heart hammered against his ribs hard enough that he could feel it through the layers of fleece and Gore‑Tex.

“This is it,” he said quietly, though everyone on the ridge already knew.

It was what they had come for.

They had no idea what else was waiting for them in the darkness below.

The Impossible Hollow

The Appalachian Mountains are among the oldest ranges on Earth. Their bones are worn and rounded, their peaks softened by time. On the surface, there was nothing remarkable about this particular ridge—just another fold of forested stone in a landscape full of them.

On satellite maps, though, it had looked different.

The initial radar pass, scheduled routinely for unrelated mineral studies, had shown a faint but curious signature: a hollow, not a little pocket or cave, but a vast chamber where solid rock should have been.

Follow‑up scans made the hair on the backs of necks stand up.

The data suggested an enclosed cavern system deep beneath the surface, sealed for at least ten thousand years, maybe far longer. No obvious entrances. No surface depressions. Just a buried, empty space the size of a sports stadium in a place where no known karst system existed.

There were legends, of course.

This was Appalachia.

Talk of “hollow hills” and “the people under the mountain” runs through old stories like roots through soil. Folklore is cheap, though. Funding is not. Thorne’s pitch to the university board had nothing to do with ghosts.

He’d called it a “closed paleoenvironmental cavity with potential for unique evolutionary and geological data.”

In simpler terms: a sealed time capsule.

He assembled a cross‑disciplinary expedition: geologists to read the stone, biologists to study whatever had survived inside, atmospheric scientists to make sure the air wouldn’t kill them, a historian specializing in pre‑Columbian America to interpret any human traces, and two veteran cave‑rescue specialists to get everyone in and out alive.

For a year and a half, they planned, scanned, and argued.

Now, with the drill bit hanging in empty space and the bore hole breathing cool, damp air, there was only one question left:

What, exactly, had they opened?

First Look Into the Dark

“Camera’s going down.”

Dr. Sarah Chen, the lead geologist, knelt by the bore hole, her gloved hands steady as she lowered a fiber‑optic scope into the black. A cable snaked from the winch beside her to a rugged monitor at her knees.

Everyone crowded in, breath steaming in the cold air.

“Depth… three hundred six feet,” she narrated, eyes glued to the screen. “Breaking into void now… okay, I’ve got wall… moisture… mineral deposits…”

Static, then a grainy image resolved: rough stone glistening with condensation, the shaft opening into some wider space below. As Chen adjusted the angle, the image widened.

“Temperature fifty‑eight degrees Fahrenheit,” she said. “Humidity very high. Definitely circulating atmosphere down there.”

“Any sign of collapse?” one of the structural engineers asked.

Chen shook her head slowly, still watching the screen.

“No. And—” She sucked in a breath. “My God, Elias. This cavity is enormous. I’m getting reflections suggesting a primary chamber at least stadium‑sized.”

It was what the radar had hinted at. Seeing it—even in fuzzy, low‑light grayscale—was something else entirely.

The rest of the day became a blur of procedure.

They drew air samples through the bore, feeding them into portable gas analyzers. The readings came back… surprisingly benign. Oxygen levels were within normal range. There were trace amounts of methane and an unusual spike in ozone—odd, but not immediately alarming.

Under normal circumstances, a sealed underground space that size should have been a stagnant tomb for air: depleted oxygen, built‑up carbon dioxide, possibly toxic gases.

This wasn’t.

Something was moving the atmosphere down there.

Structural engineers examined the bore hole, measured stress points, argued briefly, then signed off: the rock was stable enough to widen, at least for a limited access shaft.

By dawn, erosion bits and micro‑charges had carved the narrow drill hole into a vertical shaft just wide enough for a person in a harness.

Thorne volunteered to go first.

He always had.

Descent Into the Unknown

The rope hissed softly through the belay device as Thorne lowered himself into the shaft, boots braced against the rough limestone. Above, the circle of gray sky receded until it was no bigger than a coin.

Beneath his gloves, the rock told its own story.

Layer after layer of limestone bore the characteristic smoothing of ancient water. Ripples frozen in stone. Embedded shells from seas that had vanished millions of years before humans existed. But there was no known river at this depth now. No mapped aquifer big enough to carve a void like this.

That alone would have made this expedition worth the trouble.

Harnessed above him on the rope line were Chen, biologist Dr. Marcus Webb from Georgetown, and the two cave‑rescue specialists—a wiry woman named Alvarez and a broad‑shouldered man called Hines—whose job it was to make sure none of the academics died of inexperience.

As they descended, the shaft widened imperceptibly.

The air grew warmer, not colder, and carried a faint scent Thorne could only describe as “alive”—something beyond the mineral tang of typical caves.

After forty minutes, his boots touched solid ground.

He unclipped from the rope and stepped aside to give the others room to land.

When Chen’s headlamp flicked on, the beam cut through the darkness ahead. For a second, all Thorne saw was gray rock.

Then the world opened.

He was standing on the rough stone bank of an underground river.

It flowed fast and dark, twenty to thirty feet wide, vanishing into the black at both ends of the visible stretch. The cavern around it was enormous. Their headlamps couldn’t find the far wall. Above, the ceiling soared into a void spiked with monumental stalactites as fat as tree trunks.

Water whispered over stone in an endless murmur that seemed to come from everywhere at once.

Webb’s voice echoed strangely in the vast space.

“This is impossible,” he said, almost reverently. “At this depth, with no surface vents, the air should be dead. Instead, it smells like…” He inhaled again. “Like rain. Like a forest after a storm.”

He wasn’t wrong.

Thorne had noticed it too—the faint, impossible hint of organic life in the air. The smell of wet earth and vegetation, not just stone.

He swept his headlamp slowly across the cavern.

The beam picked out more than just natural formations.

On the far side of the river, barely distinguishable at first from the surrounding rock, were shapes that didn’t belong in a purely geological story.

Angles. Lines. Edges too straight, too regular.

Structures.

“Elias.” Chen’s voice was tight. “You need to see this.”

She’d knelt by the water’s edge, a thermometer probe extended into the current.

“Water temperature is sixty‑two degrees. That’s about what we’d expect for groundwater in this region.” She tapped her instrument. “But ambient air is warmer—sixty‑six, sixty‑seven. There’s a heat source down here somewhere that isn’t the river.”

She swung her own headlamp further along the shore.

The light caught on stone.

Not the random tumble of broken rock, but a pattern: blocky shapes neatly stacked, fitted together so precisely there was barely a hair’s width between them.

“Are those…” She trailed off.

“Worked stones,” Thorne finished for her.

They moved closer as a group, feet finding tentative purchase on slick rock. The “structure,” if that was what it was, jutted into the shallows: flat‑topped stones arranged in a deliberate platform, their edges worn but still clearly intentional.

No mortar, no cement. Just dry‑stone masonry of the sort humans had used for millennia—a craft older than writing.

“Could this be human?” one of the cave specialists asked quietly.

“If it is,” Thorne said, voice low, “it’s older than anything we have a record of in this region. There’s no known culture with underground stonework like this in Appalachia.”

The historian topside would argue that later. Right now, it didn’t matter. Human or not, the stonework meant one thing:

Someone had been here.

Or still was.

Signs in Stone and Circuitry in the Rock

For the next two hours, the team did what scientists do when faced with the unknown.

They measured.

They mapped.

They recorded.

The worked stones continued along the riverbank, sometimes forming low retaining walls, sometimes crumbling into half‑buried steps. In places, the rock surfaces bore markings that made Thorne’s pulse jump: long, shallow incisions arranged in geometric patterns.

Most were hexagonal—honeycomb‑like shapes with radiating lines. They resembled nothing in the Native American petroglyph catalogues he knew. They looked less like representational art and more like some form of abstract notation.

Language, maybe. Or star maps. Or something else entirely.

Webb, meanwhile, had crouched beside a patch of faintly glowing moss on the damp stone, his handheld scanner humming.

“This isn’t any cave biota I recognize,” he said. The soft blue‑green halo from the moss threw eerie light across his face. “The luminescence is too strong for normal cave adaptation. And early genetic markers aren’t matching anything in our databases.” He glanced up, eyes bright. “Whatever this is, it’s not just another mold.”

Before Thorne could respond, Chen’s radio crackled at her shoulder.

“Surface to base,” came a tinny voice through the static. “We’re seeing something strange in the seismic data.”

“Go ahead,” Chen answered, stepping aside.

The reply was slow, measured, and not a little unnerved.

“We’re picking up minor tremors from beneath your current position. They’re small—nothing to worry about structurally—but they’re rhythmic. Regular. The same signal every four minutes, thirty‑seven seconds. It looks… artificial.”

Chen’s gaze met Thorne’s in the lamplight.

“Natural seismic events don’t do that,” she said simply.

He knew.

Earthquakes are chaotic. Rock shifts where it must, not on a schedule.

If something below them was shaking the ground at precise intervals, it wasn’t geology.

It was something else.

“Copy,” Thorne told the radio. “We’re going deeper.”

Deeper In

They followed the river.

It curved away from their entry point, flowing through a narrower passage into a second chamber. This one was smaller by comparison, but still vast enough to swallow a cathedral.

Here, the glowing moss was thicker.

It coated stone outcroppings and slid like phosphorescent frost along the walls, casting a dim, otherworldly glow that made their electric headlamps suddenly seem harsh and foreign.

For the first time, they flicked their lights down to half‑power.

In the natural glow, the cavern felt less like a hole in the earth and more like a place that had grown on purpose.

And that’s when they heard it.

Not water. Not the distant drip of mineral‑rich droplets forming stalactites.

Something else.

A low, resonant tone that seemed to rise from the stone itself—too deep to be a voice, too steady to be random. It thrummed in Thorne’s chest more than in his ears, like standing too close to a massive engine.

The cave‑rescue specialists went instantly alert, hands brushing the gear on their belts.

“What is that?” Webb whispered.

The sound came again, longer this time, like a note being held and then released. It carried with it a subtle vibration in the air, as if the entire chamber was humming.

Then, ahead of them, the water moved.

Not gently, not the way a current licks at rock, but with the distinct displacement of something large shifting its weight.

Then another movement.

And another.

Thorne threw up a hand automatically, the signal drilled into field teams worldwide: Stop. No one move.

His heart pounded so hard he could feel each beat in his throat.

Something was in the river.

Multiple somethings.

They stood perfectly still, their headlamps angled down, beams skimming low over the water.

The glow of the moss picked out ripples. Shadows. Bulk.

Thorne swallowed hard, lifted his headlamp a fraction, and let the light crawl further out into the center of the river.

The beam caught fur.

Wet, matted, reddish‑brown fur wrapped around a massive, upright form.

He swung the light slightly to the left.

Another.

And another.

As the others raised their own lamps, cones of light intersected and brightened, pushing back the gloom.

The scene that resolved made Thorne’s blood run cold.

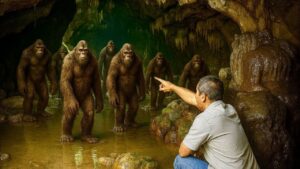

Face to Face

There were six figures clearly visible in the shallows, their water‑darkened fur clinging to powerful bodies. Beyond the reach of the headlamps’ glare, more shapes hinted at a larger group—seven, eight, maybe more.

They stood upright in the river, bipedal, their posture eerily human. But everything about their proportions was wrong if you expected human bodies.

They were too tall—most at least seven feet, some closer to eight.

Their shoulders were impossibly broad. Arms hung long enough that their hands reached mid‑thigh or lower. Thick fur, soaked and dripping, framed torsos that were simply larger than human skeletons could support without collapsing.

Thick necks. Barrel chests. The outline of heavy, dense muscle.

And their faces—

Thorne knew in an instant these were no misidentified bears. No men in suits. No tricks of light.

The faces were neither fully human nor fully ape, but something in between. Heavy brow ridges jutted over deep‑set eyes. Noses were wide and flat. Mouths were broad, lips capable of subtle movement. Hair framed cheeks and jaws like beards.

But the eyes.

The eyes were not animal.

They were focused, moving, tracking. They were aware.

The one in the center was larger than the rest. It stood a few feet ahead of the others, clearly the point of contact, clearly—if his primate studies meant anything—the leader.

It met Thorne’s gaze across the water.

In that locked look, Thorne understood with a clarity that left no room for denial: he was being assessed.

Measured.

Perhaps judged.

Beside him, Sarah Chen made a strangled sound, somewhere between a gasp and a sob. Marcus Webb stood rigid, breath shallow, the part of his mind that loved clean data struggling to reconcile the impossible forms in front of him with everything he thought he knew about the family tree of hominids.

One of the cave specialists murmured a prayer under his breath.

Everything in Thorne—all the ancient, primitive wiring beneath his educated cortex—screamed one command:

Run.

But he did not run.

He forced himself to think like a scientist. Like a guest in someone else’s home.

Slowly, deliberately, he lowered himself into a crouch, making his profile smaller, less threatening. His raised hand stayed out, fingers spread in a universal signal of “stop,” this time meant for his own team.

Behind them, on the surface, seismic sensors had recorded rhythmic tremors from below.

Now Thorne understood why.

They hadn’t drilled into an empty geological curiosity.

They had drilled into someone’s living room.

The Tribe

For long seconds, no one moved.

The tribe in the water—because that was what they were, Thorne’s mind supplied, a tribe—stood silent, their chests rising and falling with slow, steady breaths.

As his eyes adjusted further, Thorne began to see details that theory had never prepared him for.

The leader wore something around its neck.

At first, he assumed it was just tangled fur. Then his scientist’s eye caught structure: a band of woven material, possibly plant fiber, from which hung small objects that looked like carved bone or antler.

Ornamentation.

Decoration.

Culture.

Another individual, just to the leader’s left, held something in its right hand. Its fingers were long and thick but dexterous, curling easily around the object.

Not a club. Not a random rock.

A tool.

Thorne could see, even from a distance, the careful shaping along the stone’s edge, the way it had been hafted onto a handle wrapped with what might be hide or sinew.

He had spent his career cataloguing stone tools crafted by beings long vanished. Now he was looking at one held by something very much alive.

These were not animals that had stumbled into the cave and stayed.

They were people.

Hairier, taller, older in lineage than Homo sapiens, but people.

His mind raced.

Gigantopithecus, Webb had said behind him, voice barely above a whisper. The extinct giant ape of Asia, known only from teeth and jaw fragments in the fossil record, gone for three hundred thousand years.

“They’re not extinct,” Chen said, barely audible. “They’re right there. They’ve been isolated. For how long?”

We have legends, Thorne thought distantly, remembering Appalachian tales of Bigfoot and Sasquatch told in low voices on front porches. Wild men in the hills. Tall, hairy shapes in the fog.

Folklore had always been a convenient bucket to dump uncomfortable truths into.

What if some of those stories weren’t fantasies at all, but cultural memories of encounters with cousins who had retreated out of sight rather than be wiped out?

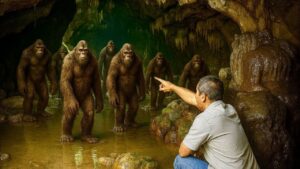

The leader moved.

Every muscle in Thorne’s body stiffened.

The massive figure raised one hand, slow and deliberate. It pressed that hand against its chest, fingers splayed, in a gesture that was startlingly familiar.

Then it extended its arm toward Thorne, palm forward, fingers spread.

The cave, the river, the glowing moss, the pounding in his ears—all of it seemed to narrow around that simple motion.

A greeting.

Recognition.

An invitation to communicate.

Thorne’s throat tightened. His eyes stung unexpectedly.

Everything he’d ever taught his students about human uniqueness, about singularity, about being the only tool‑using, culture‑bearing primate line left on Earth, cracked and shifted.

With excruciating slowness, mirroring the creature’s movements exactly, he lifted his own hand.

He pressed it to his chest.

Then extended it, palm out.

The leader’s eyes tracked the motion.

Its mouth opened slightly, revealing teeth that were neither fully carnivore nor herbivore. When it vocalized, the sound that came out was not a roar or a mindless bellow.

It was structured.

Complex.

A layered sequence of tones and rhythms that made the hair rise on Thorne’s arms. It wasn’t a language he could translate, but his brain recognized pattern when it heard it.

Behind the leader, the others remained motionless. Their eyes flicked between their leader and the humans, waiting.

For what, Thorne didn’t know.

For his answer, maybe.

For a decision.

Two Worlds Collide

This wasn’t how it was supposed to go.

The expedition protocols they’d written back on campus had anticipated all kinds of risks: unstable rock, bad air, toxic spores, flash floods in underground rivers.

None of them had considered intelligent, tool‑using inhabitants.

“Elias,” Chen said, voice shaking, “what do we do?”

The question rang through his mind like the tremor from the seismic monitors.

What do you do when you drill into a hidden world that has every right to exist without you?

He took in the scene again, forcing himself to catalogue it as best he could while adrenaline fogged his thoughts.

Behind the line of figures in the river, the rocky shore rose into the faintly lit outlines of more structures. Lean‑to‑like shelters made of stacked stone and carefully broken stalactites, their overhangs forming dry spaces clearly used as sleeping or gathering areas. Above those, the cavern wall was covered with carved symbols in dense bands—hundreds of them, layered like sentences, like histories.

They weren’t just surviving down here.

They were living.

They had shelter, organization, a clear social structure. They had art. They had jewelry. They had tools. They had some form of language.

And they had just been invaded.

Thorne’s mind sprinted through potential futures, none of them good.

If they reported exactly what they had found, this place would be overrun.

Government agencies. Military. Academic institutions. News crews. Hunters. Conspiracy theorists.

Some would come with noble intentions: to study, to understand, to “protect.” Others would come with cameras or guns or both. But even the most well‑meaning intrusion would tear this world apart.

Exposure is a kind of violence.

“Elias.” Chen’s whisper sharpened. “They’re moving.”

The tribe in the water had shifted.

Not forward. Not in attack.

Sideways.

They spread out, forming a line across the width of the river, bodies spaced just far enough apart to make their blocking intent clear.

You will go no further.

The leader remained in the center. Its gaze never left Thorne’s face.

In those dark eyes, Thorne saw something that chilled him more than any roar could have.

Calculation.

They were thinking through him in exactly the way he was thinking through them.

Then the leader bent.

It moved slowly, telegraphing its intention, as if it understood that sudden movement from something its size might trigger panic.

Its hand dipped into the river and came up cradling a stone.

Not just any stone.

The same flaked, hafted hand axe Thorne had seen before.

The creature lifted it a little higher, letting the humans see it clearly. Then it lowered its arm and placed the tool with deliberate care on a flat rock at the edge of the water.

The message was multi‑layered and painfully clear.

We have tools.

We have weapons.

We are not defenseless.

“We’re not the only dangerous ones in the room,” Webb breathed.

Thorne’s mind spun back through time again. Ten thousand years of estimated isolation suddenly seemed less certain. What if they hadn’t been fully sealed? What if there had been breaches before? Tunnels, collapsed and re‑closed. Encounters with humans passed down as warnings in both species.

We have our legends of “wild men” and “Bigfoot.”

What legends did they have about us?

The leader made another sound, sharper this time. A command.

The others turned in unison and began to move away, deeper into the cave system, vanishing, one by one, into the gloom beyond the range of the moss light.

Only the leader remained.

It raised its hand again.

This time, it pointed.

First at the humans.

Then up, toward the tunnel they had descended.

Then at itself, and toward the darkness behind it where its people had gone.

The gesture, combined with that intense, unwavering stare, left no room for misinterpretation.

You go your way.

We go ours.

Thorne felt the weight of that choice settle on his shoulders.

If they pushed forward now, trying to see more, to map, to measure, to extract samples, there would be consequences. The tribe had made that plain. And even if they somehow survived that immediate confrontation, the damage their very presence would do—through microbes, through noise, through fear—would ripple through this underground society.

If they turned back, they would be leaving behind the greatest discovery in the history of anthropology.

Answers to questions about human evolution, about the breadth of the hominid family tree, about cognition and culture, stood in the water in front of him, looking him in the eye.

“Elias,” Chen whispered, urgency and fear braided together. “We need to go. Now.”

He thought of fossil skulls in museum drawers. Of debates about Neanderthals and Denisovans and extinct ape lineages. Of academic careers built on fragments of bone.

Then he thought of the woven necklace around the leader’s neck.

Of the tool laid down like an offering or a warning.

Of eyes that had watched them from the moment they entered the chamber.

“We leave,” he said hoarsely.

He pressed his hand to his chest one more time. Then, keeping his movements slow, pointed toward the entrance tunnel.

The leader watched him.

For a second—just one—Thorne felt something pass between them. Not quite understanding, but something like mutual recognition.

In another world, another time, they might have sat around a shared fire, trading tools, stories, myths.

In this one, they were strangers meeting in the dark.

The leader turned without another sound and followed its people into the depths, its massive form swallowed by shadow.

The chamber was suddenly, startlingly empty.

The only proof that anything had stood there at all was the hand axe on the rock, water still dripping from its edge.

The Hardest Decision

They didn’t run.

Every instinct screamed at them to scramble up the rope as fast as possible, but panic gets people killed underground. Hines and Alvarez kept the team moving at a controlled pace, clipping into the rope one by one, hands careful on the ascenders.

They didn’t speak until they were halfway up the shaft.

When Thorne finally hauled himself over the lip of the opening into sharp, cold daylight, the sun felt wrong on his skin. Too bright. Too exposed.

The surface team surged toward them, questions firing.

“What did you see?”

“How big is it?”

“Any life down there?”

“Did the tremors stop?”

Thorne held up a shaking hand.

“Give us a minute,” he said.

He walked away from the shaft until he found a flat rock and sat heavily, elbows on his knees. Sarah Chen sank down beside him, face pale. Webb hovered nearby, eyes unfocused, mouth opening and closing wordlessly.

“What do we tell them?” Chen asked finally, voice barely more than air.

Thorne stared at the freshly cut shaft, at the scar they had drilled into the mountain’s skin.

He thought of the line of tall, fur‑clad bodies in the water below. Of the leader’s hand pressing against its chest. Of the nicotine‑stained conference rooms where officials would sit around tables and decide what to do with such knowledge.

If he told the truth, this ridge would become the center of the universe.

Fences would go up.

Black SUVs would arrive.

Contracts would be written that no one outside classified circles would ever see.

They would come with good intentions, some of them. To study. To “protect.” To learn.

But human curiosity is a tidal wave.

Anything fragile in its path gets swept away.

If he lied—if he suppressed the data, falsified the reports, sealed the shaft and walked away—he would be burying the single most important anthropological discovery of his lifetime.

No one would ever hear the complex, layered vocalizations he’d heard in that chamber. No one would ever trace the sharp edge of that hand axe and know it had been shaped by living hands, not ancient ones.

“We seal it,” he said at last.

Webb stared at him.

“You’re talking about burying the biggest discovery in our field,” he said, anger and grief warring in his tone.

“I’m talking about not turning their home into a zoo,” Thorne replied.

He forced his voice to stay level.

“We broke into their world. They let us leave. They even told us how far we were allowed to go. We don’t get to reward that restraint by bringing an invasion down on them.”

Chen nodded slowly.

“They’ve survived this long because we didn’t know about them,” she said. “Because the mountains hid them.”

“Exactly.” Thorne looked at the shaft one more time. “If we expose them, we might as well sign their death sentence.”

The argument that followed was short, intense, and bitter.

Science is built on sharing knowledge, not burying it. They all knew that. But science, in its best form, is also built on ethics.

Some truths, they realized, can destroy the thing they describe simply by being revealed.

Three days later, the site was gone.

On paper, at least.

The borehole was collapsed and buried under tons of rock. The official report cited “catastrophic structural instability” in the cavity and a “natural collapse” during preliminary exploration. The ground‑penetrating radar data that showed the full extent of the hollow was wiped, corrupted in what the logbooks called an “equipment malfunction.”

The expedition packed up and left the ridge.

The mountains settled back into their old silence.

The Secret Beneath the Ridge

Thorne kept the truth.

Not in peer‑reviewed journals or conference presentations, but in private notebooks and encrypted files. In diagrams he scribbled late at night and hid in a safe deposit box. In the rough sketch of a hand extended, palm out, he found himself drawing absent‑mindedly on napkins.

He kept it in his nightmares, too—the ones that jolted him awake, sweating, back in that glowing chamber, a line of tall shapes watching him from across black water.

He knew what the official story would eventually become.

He could already hear it in the way some of his own team talked about the expedition when others were listening.

“Cavity turned out to be too unstable.”

“Just a big, empty space.”

“Nothing but stalactites and bats.”

The world had no shortage of mysteries. It would move on. The ridge would blend back into the vast, green anonymity of the Appalachian chain.

But sometimes, late at night, when the hum of his refrigerator sounded a little too much like that deep, resonant note in the cave, Thorne would close his eyes and see them again.

The towering silhouettes, fur slicked dark with river water.

The woven band around a thick neck.

The hand axe, sharp edge catching the moss light.

The eyes—so like his own in their calculation—that had met his across the gulf between their species.

He would wonder what stories they told of the day the ceiling of their world shook and a hole opened, and strange, pale creatures in bright gear descended on ropes.

If they warned their young about the “people from above” the way humans warned theirs about shadows in the woods.

He hoped, more than he’d ever hoped for tenure or grants or prestige, that they had gone on with their lives.

That the gardens he glimpsed in the faint glow deeper in the cavern still flourished.

That the carvings on the walls continued to grow with new lines, new histories.

That the deep, rhythmic tremors the surface team had recorded were not an omen of collapse, but the pulse of some cultural practice—drumming, perhaps, or ritual—that would continue, unbroken, in the dark.

Because there are some tribes, he had come to believe, who are meant to remain in shadow.

Not because they are lesser.

But because the bright, hungry light of the surface world is more dangerous than the dark.

Some discoveries would change textbooks.

This one, if unleashed, could erase an entire people.

So he made the only choice he felt he could live with.

He gave them back their silence.

And left the mountains to keep their secret.