German Women Pows Lived On Only Bread Crumbs For 5 Months — When Cowboys Set The Table, They Refused

The Table in Texas

June 18th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas.

The heat arrived before anything else. It pressed down on the wooden tables, on the gravel beneath our shoes, on the backs of our necks where sweat gathered and refused to dry. Texas heat didn’t rush or shout; it settled in slowly, confidently, as if it knew it belonged here.

.

.

.

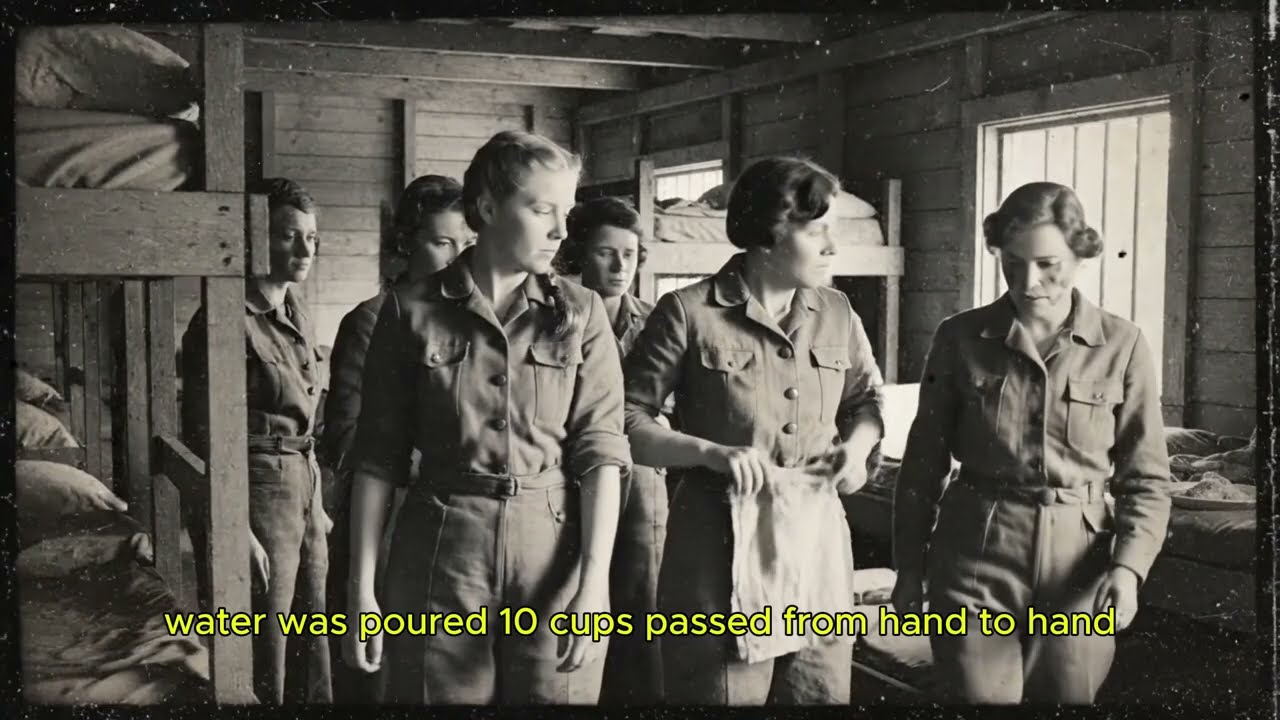

We were marched into the open-air mess area just before noon. No walls, no ceiling, just long wooden tables, rough benches, and a serving line set up under a tin awning that shimmered in the unforgiving sun. I remember feeling the smell before anything else. Not the typical stench of a prison—sweat, disinfectant, and the ever-present scent of fear. This was different.

The smell was rich and warm, like something cooking slowly, carefully. Hot fat, soft bread, a faint curl of smoke drifting upward. It settled on us like a weight, reminding the body of something it had long forgotten—comfort.

My stomach tightened, but not from hunger. No, this was confusion. I looked around, feeling the tension rising in me. This was not what a prisoner’s meal was supposed to look like. The tables were being set. Real tables. And chairs. Real wooden chairs, not the benches we had gotten used to, but chairs with backs. Chairs you’d see at a Sunday dinner, not at a prisoner of war camp. The scene before me felt like a dream, one I couldn’t quite place, but I knew it didn’t belong in this place.

Across the yard, men in denim shirts moved back and forth, setting up the tables. One spread a white cloth across a surface and smoothed it with both hands, as if it mattered. White. I blinked hard, convinced my eyes were deceiving me. But no, it was real. Another table followed, then another. Plates appeared. Ceramic plates. Forks and knives followed. Real utensils. No one had ever fed us with plates, with silverware. The very idea felt foreign, unreal.

A murmur passed through the women around me. No one spoke out loud, but the word was clear in everyone’s mind: meat. Meat. We hadn’t seen meat in months. The ration lines in Europe had stripped us of any hope of ever tasting something as simple as a slice of pork or a beef stew. Meat had become a luxury. It had become a memory.

At first, no one moved. My body, conditioned by five months of captivity, stood frozen. I wasn’t sure what this was—this wasn’t supposed to be a meal. Prisoners didn’t eat like this. Not in Germany, not in France, not anywhere we’d been. Meals were supposed to be an obligation, not an invitation.

And yet here we were, staring at tables set with plates and glasses of water, at food that smelled so good it made my body react before my mind could catch up. We were all hungry, but this was not hunger. It was something deeper—fear. Fear that this was a trick, that they would use our hunger against us. Fear that the food would be a part of something larger, something meant to humiliate us.

Then one of the cowboys—the men in hats and sun-creased faces—walked toward us and stopped a few steps away. He did not raise his voice. He did not smile broadly or frown. He simply gestured toward the tables. He waited.

There was no rush, no impatience. Just an invitation. Still, we stood frozen. My legs felt like they were made of lead, my body unsure whether to trust what it saw. In Germany, the thought of sitting at a table as a prisoner, to be served food, was unthinkable. The idea of being treated like an equal—no matter how small the gesture—had been removed from our minds long ago.

One of the women beside me whispered, barely audible, “For them. It must be for them.” I wanted to believe her. I needed to believe that. This could not be meant for us.

And yet, it was. Plates appeared before us. Real plates. Forks. Knives. Water. The smell of warm bread filled the air. The chairs were empty, waiting for us, but still, no one moved. The air hung thick with a strange tension, like a moment suspended between fear and possibility. It was then that I realized what was happening.

The Americans weren’t testing us. They weren’t trying to trick us. They were simply living their values. They had learned to offer something not because it would be demanded of them, but because they understood the power of restraint.

The moment lingered. We still didn’t move. And then, with no command, one of the soldiers stepped forward. He pulled a chair back just a few inches and stepped aside. He didn’t speak. He didn’t need to.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, I stepped forward. My legs were stiff, hesitant, but my feet found their way to the table. The chair was waiting. I didn’t hesitate now. I sat down.

It wasn’t dramatic. No one looked at me. The men stood back, giving me space. Their movements were effortless. There was no scrutiny, no judgment. They were not watching for fear. They were watching for normality. For someone to make a choice that belonged to them. No one forced us to sit. No one told us to eat.

And so, we did. We ate, but not quickly. We ate slowly, with care, each of us digesting not just the food but the experience. The bread was soft, warm, comforting. The meat—real meat—was tender. The potatoes, the vegetables, the water, all of it was simple, generous, and entirely unexpected.

I ate without thinking at first, but then something in my chest began to loosen. My body—starved, neglected—reacted as if it were finally being seen again, not as a prisoner, but as a person. I ate without shame, without fear, for the first time in months.

And that’s when I realized. The power wasn’t in the food. It wasn’t in the tablecloth or the utensils or the meat. It was in the act of sitting down to eat without being humiliated, without the threat of punishment. It was in being treated as if you were worth something, simply for being human.

After a while, the moment began to fade. No one rushed. The cowboys moved back, standing off to the side, chatting among themselves, leaning against posts, relaxing as if this was just another day. I looked at the table, the empty plates, the crumbs, and I understood something deeper than hunger.

This wasn’t a gesture. It wasn’t charity. It was something ingrained. It was what a country does when it understands that strength isn’t measured by cruelty, but by restraint. And this was a country that knew it didn’t need to break its enemies to win.

As I sat there, savoring the final bite, I understood what I had witnessed. America, at its core, wasn’t about dominance—it was about confidence. The confidence to feed even those you considered your enemy, not out of pity or need for gratitude, but because you had the strength to do so without fear.

That simple, ordinary act of sharing a meal had defeated me in a way no army ever could. It had made me see that the greatest power of all was not in taking, but in giving. That was the moment I realized what had happened. It wasn’t just the food that had nourished me—it was the humanity behind it.

And as I sat back, watching the others slowly finish their meals, I realized that this moment, so simple, would stay with me for the rest of my life. Because it wasn’t just a meal. It was a lesson, a lesson that America had shown in quiet, unspoken confidence, and one that I would never forget.

When I left this place, when I walked away from the barbed wire and the barracks, I carried something with me far more valuable than any food I had ever eaten. I carried the memory of a country that understood what true strength was. And as I looked back over the years, I would come to understand that it wasn’t just a victory in war that America had won—it was a victory in the human spirit.

A victory in kindness.