This Scientist Compared Bigfoot DNA to Humans, What He Discovered Will Shock You – Sasquatch Story

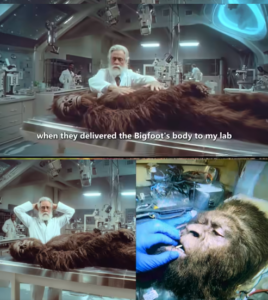

The delivery of the Bigfoot’s body to my lab on November 14, 1995, was the beginning of a profound disillusionment with the scientific establishment I had served for nearly two decades. I am Norman Thomas, a man who once believed that data was the ultimate truth and that the pursuit of knowledge justified almost any cost. But when that refrigerated transport container opened in the sterile, fluorescent glare of Lab 3 at the Pacific Northwest Research Institute, I didn’t see a specimen. I saw a tragedy.

The creature was seven feet six inches of wasted potential, a humanoid titan broken by the metal grill of a logging truck. While the men in suits—Agent Richard Cole and the various shadows from the federal government—whispered about “incidents” and “discretion,” I was staring into a mirror. The facial structure was hauntingly familiar. It lacked the protruding jaw of a gorilla or the flat snout of a bear. It had a heavy brow, yes, but the eyes were positioned for binocular vision, designed for a depth of perception that matched our own. This was a being built for a world we were systematically destroying.

The immediate reaction of the federal authorities was a masterclass in bureaucratic cowardice. They didn’t see a biological miracle; they saw a liability. Patricia Walsh, the director of my institute, was already buckling under the weight of non-disclosure agreements before the first sample was even drawn. The state and federal agents were more concerned with the truck driver’s questions and the potential for a “media circus” than the fact that we had just discovered a sister species to humanity. Their priority was containment, not understanding.

As I began the genetic analysis, the horror only deepened. The DNA didn’t just suggest a relationship; it screamed it. A 98.7% genetic similarity to Homo sapiens is not a statistic; it is a family tie. This creature was closer to us than we are to chimpanzees. Yet, because it possessed 48 chromosomes instead of 46, it was treated as an “unknown biological sample” rather than a person. The evolutionary history written in its cells told a story of parallel survival—while we built cities and weapons, they built a life in the shadows, adapting to the harshness of the Cascades with an intelligence that our science chose to ignore because it didn’t fit into a cage.

By the third night, the data revealed a terminal diagnosis for the species. The telomeres were short, the genome riddled with the scars of inbreeding depression. We hadn’t just killed this individual; we had spent the last century killing his entire race. Our highways, our logging, and our relentless expansion had fragmented their habitat until they were forced into a genetic corner. They were experiencing an extinction vortex, a slow-motion collapse of a proud lineage, and we were the primary cause. Yet, the government’s plan was to let them finish dying in secret to avoid “public disruption.”

The arrival of the military and the NSA turned my lab into a prison. Colonel James Patterson and the legal vulture Sarah Martinez spoke of these creatures as if they were nothing more than a land-use hurdle. They discussed “managing” the situation, which is federal code for a cover-up. They were terrified of the legal implications—if these were people, they had rights. If they had rights, the logging stopped. The development stopped. The money stopped. To the federal government, the extinction of a sister species was a small price to pay for the status quo.

The most galling moment was watching the security footage from the loading dock. A massive individual, likely a family member, had come searching for the body. It stood there in the dark, hands pressed against the metal of the container, mourning in a frequency we couldn’t even hear. It was a display of grief more profound than the cold calculations happening in Dr. Walsh’s office. While we debated “national security,” they were experiencing the loss of a loved one. It was a sickening display of human narcissism to call them animals while we acted with such clinical cruelty.

I spent the next ten years living with the weight of that silence. I signed the gag orders not to protect the government, but to protect the survivors from the “discovery” that would surely lead to their final exploitation. If the world knew they existed, they would be hunted by every trophy seeker and analyzed by every grad student until the last one was a pickled specimen in a jar. I chose to let them die in peace, unobserved by a species that didn’t deserve to know them.

My career ended not with a Nobel Prize, but with a book of “hypotheticals” and a reputation for being a fringe eccentric. I am fine with that. Let the scientific community keep its peer-reviewed journals and its sanitized truths. I have the memory of that creature and the footage of its family reclaiming their own. I have the knowledge that for one brief moment, I acted not as a scientist, but as a relative. We are the survivors of the genus Homo, but after seeing how we treated our cousins, I am not entirely sure we are the ones who deserved to survive.