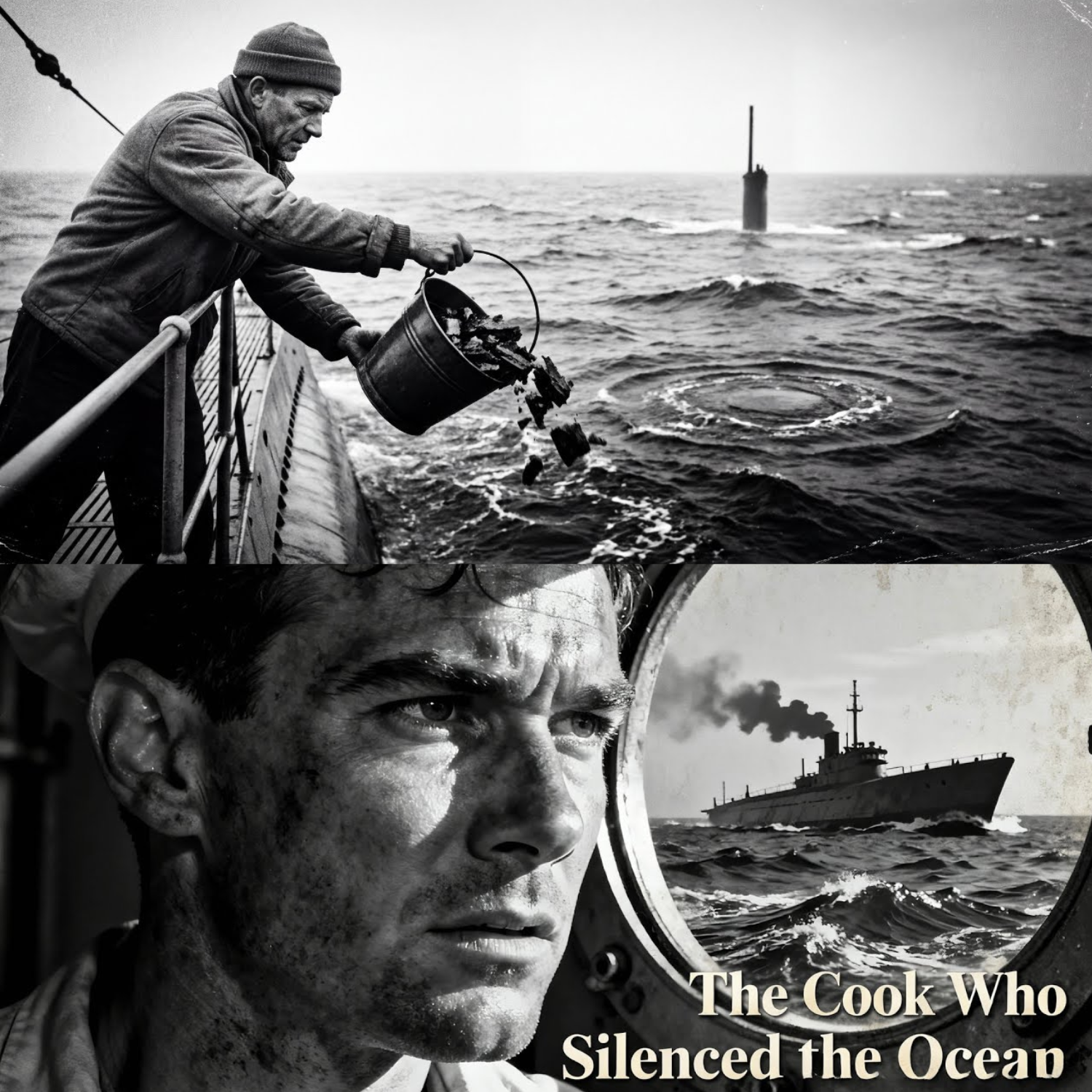

Why One Submarine Cook Started Throwing “Scraps” — And Sunk Every U-Boat He Found

The Day Garbage Turned the Ocean Into a Weapon

The North Atlantic had a way of breaking men.

On March 14th, 1943, the sea rolled gray and endless, 380 miles southwest of Iceland. A cold wind cut across the deck of HMS Starling, slicing through wool coats and nerves alike. Eleven hours. That’s how long Commander Frederick Walker’s escort group had been hunting ghosts beneath the waves.

Eleven hours of sonar pings.

Eleven hours of false contacts.

Eleven hours of knowing that somewhere below, unseen men waited patiently—with torpedoes already aimed.

Then the sonar operator went pale.

“Multiple contacts. Bearing 270. Closing fast.”

Walker leaned over the chart table. Three U-boats. A coordinated wolfpack. The kind that had already sent hundreds of merchant ships—and thousands of sailors—to the bottom of the ocean. Men burned alive in oil slicks. Men frozen solid before rescue could reach them. Britain was bleeding faster than it could replace ships.

And then something appeared on the surface.

“Sir… objects in the water.”

Walker stepped to the bridge wing. Floating nearby were scraps of bread. Potato peelings. Vegetable waste. Fresh.

Garbage.

No submarine would dump food waste while being hunted. German doctrine was absolute: silence, discipline, no trace. Anyone who broke that rule was dead—or incompetent.

Walker felt something cold settle in his chest.

This wasn’t waste.

It was a lie.

Half a world away, weeks earlier, another man had been staring at garbage with the same uneasy realization.

Arman Swisser was not supposed to change the course of a war.

He wasn’t an officer. He wasn’t a tactician. He was a torpedoman on the USS Barb, temporarily reassigned to galley duty as punishment for gambling. His hands smelled of grease and potato skins, not glory.

But Swisser paid attention.

Every time he dumped food waste through the submarine’s trash disposal unit, Japanese escorts changed course—within minutes. Not randomly. Precisely. As if they were reading a message written on the ocean’s surface.

He watched it happen again.

And again.

And again.

“They’re tracking our garbage,” he finally told the captain.

The officers laughed.

Then they tested it.

What they found was terrifying.

Bread floated for forty minutes.

Vegetable peelings spread into fan-shaped trails.

From the air, the debris revealed heading, speed—intent.

Garbage wasn’t disappearing.

It was betraying them.

And if garbage could betray a submarine, it could also deceive one.

The first time Captain Eugene Fluckey tried it in combat, it felt insane.

At dawn, off the coast of Formosa, the USS Barb released forty pounds of food waste into the sea. Then she dove deep and turned away—running in the opposite direction.

The Japanese destroyers found the debris and attacked it ferociously, dropping depth charges into empty water while Barb slipped silently behind the convoy.

Minutes later, torpedoes slammed home.

Ships burned.

Fuel ignited.

Men screamed.

The escorts realized too late they had been hunting trash.

Fluckey called it false trail debris deployment.

He wrote the report.

Someone forwarded it.

Someone else nearly dismissed it.

Then Commander Frederick Walker read it.

Back aboard HMS Starling, Walker watched the floating scraps drift across the waves. He imagined a German commander below, confident, disciplined, already preparing his textbook escape.

Walker smiled grimly.

“Prepare debris deployment,” he ordered.

Bread. Potatoes. Vegetable waste—dumped deliberately, visibly, shamelessly.

The German commander saw it through his periscope and made the logical choice. The trained choice. The choice that had saved him dozens of times before.

Dive deep.

Run silent.

Wait for the British to exhaust themselves.

He had no idea that this time, the British were not chasing.

They were positioning.

New sonar tracked deeper than ever before. Hedgehog mortars waited, silent and deadly, exploding only on contact.

When they fired, the ocean seemed to tear itself open.

Seven explosions struck the U-boat’s pressure hull.

At nearly 500 feet below the surface, the submarine shattered like glass.

Forty-nine men died instantly.

No warning.

No escape.

No time to pray.

The remaining U-boats panicked.

They dove deeper—believing depth meant safety.

It didn’t.

At maximum depth, submarines were slow. Blind. Trapped by their own fear. Walker’s ships boxed them in, dropping charges set to depths the Germans never believed the British could reach.

Within seventy-four minutes, three U-boats were gone.

The convoy passed untouched.

For the first time in the war, the hunters had become predictable—and the prey had learned how to lie.

April became May.

May became known as Black May in German naval history.

U-boats died faster than crews could be trained.

Veteran commanders vanished beneath the waves.

Wolfpacks dissolved into scattered, frightened одиs.

Garbage had done what torpedoes alone could not.

It had broken doctrine.

Arman Swisser never received a medal.

He went back to frying eggs.

Commander Walker never lived to see the war’s end—he collapsed from exhaustion after thirty-four months at sea.

But their idea lived on.

Modern submarines deploy decoys, noise-makers, false signatures—descendants of floating potato peels. The principle remains unchanged:

Make the enemy believe you are somewhere you are not.

History remembers radar.

History remembers codebreakers.

History remembers great admirals.

But sometimes, history turns on a man nobody notices—standing in a galley, watching garbage drift across the sea, and daring to ask:

Why does this matter?

Because on one quiet stretch of ocean in 1943, trash became truth.

And truth became a weapon.