Autistic Black Boy Called ‘Slow’ by Classmates, Until He Solved the Math Olympiad in Minutes

.

.

The Invisible Genius: The Story of Eli Turner

Eli Turner saw mathematics everywhere. In the rhythm of footsteps echoing down Jefferson Middle School’s hallways, in the intricate patterns of light filtering through cafeteria windows, and even in the geometric precision of crumpled paper balls that his classmates mercilessly threw at him. Those classmates called him slow and said his brain was broken, but Eli was quietly solving problems that would stump even their teachers. He filled grocery receipts with proofs that belonged in university textbooks, proofs that no one but Eli understood.

No one knew about Vector King—the mysterious online mathematician helping professors crack impossible theorems. No one knew that when Dylan Morrison tripped Eli in gym class or erased his equations before turning them in, Eli was calculating probability patterns, finding solace in numbers that never mocked or betrayed him. But in three weeks, everything would change. Eli Turner was about to walk into the state math Olympiad and do something extraordinary.

The cafeteria at Jefferson Middle School buzzed with the familiar chaos of lunchtime. Trays clattered against tables, laughter bounced off the walls, and conversations overlapped into an indistinguishable hum that would have been deafening to anyone not used to it. The smell of reheated pizza mingled with industrial cleaning supplies and the faint sweetness of chocolate milk, creating an atmosphere unique to school lunchrooms everywhere.

In the far corner, away from clusters of chattering students, 14-year-old Eli Turner sat alone at a table meant for six. His dark eyes focused intently on the notebook spread before him, pencil moving in precise strokes across the page. The patterns emerging weren’t doodles or random sketches to pass the time; they were mathematical sequences, each line building upon the last in a complex dance of numbers and symbols that would have stumped most high school seniors, possibly even college students.

Eli’s hand moved with practiced ease, his mind translating abstract concepts into visual representations that made perfect sense to him, even if no one else could see their beauty. The equation he worked on dealt with prime number distributions, something he’d been puzzling over since he woke that morning. The way numbers related to each other fascinated him endlessly. Where others saw random digits, Eli saw patterns, relationships, stories waiting to be told through mathematical proofs.

His pencil scratched softly against the paper. The sound was lost in the cafeteria’s chaos but rhythmic and soothing to his ears.

“Look at him,” a voice carried over from a nearby table where the basketball team usually sat. “Sitting there staring at his book like always, but he doesn’t even understand what he’s writing.”

Another voice joined in, louder this time, belonging to Marcus, one of Dylan Morrison’s friends. “My dad says people like him are just slow. Takes them forever to process stuff. That’s why he never talks in class.”

“Yeah, and he does that weird thing with his hands when he’s thinking,” added another student, demonstrating by flapping his hands mockingly. “Total freak behavior.”

Eli’s pencil paused for just a moment. He heard every word, processed every cruel inflection, cataloged each voice for future avoidance. His hands, which did indeed move when he was deep in thought, helping him process complex ideas, stayed deliberately still on the table. He’d learned long ago that reacting only made things worse.

Instead, he adjusted his worn hoodie, pulling it slightly forward to create a smaller field of vision, and continued working on his equations, finding comfort in the predictability of numbers where human behavior offered none.

The hoodie itself was a deep navy blue, purchased three years ago from a thrift store and now soft from countless washes. It had become something of a security blanket for Eli. The weight of it on his shoulders provided a gentle, consistent pressure that helped him stay grounded in overwhelming environments like this one. The front pocket held three pencils—always three—sharpened to the exact same length each morning before school.

“Hey, Turner.” The voice was louder now, directed specifically at him. It was Dylan Morrison himself, standing up from his table and walking over with the confident swagger of someone who’d never been told no in his life. Dylan was everything Eli wasn’t: loud, popular, athletic, with perfectly styled blonde hair and clothes that still had creases from being freshly purchased. His father was a real estate developer. His mother was on the school board. And Dylan himself was the star of the basketball team despite being in eighth grade.

Eli didn’t look up, hoping ignoring Dylan would make him lose interest and walk away. But Dylan didn’t operate on normal social rules. He thrived on attention, and Eli’s lack of response only seemed to encourage him.

“I’m talking to you, Turner,” Dylan said, now standing directly beside Eli’s table. “What are you even writing? Let me see.”

Before Eli could react, Dylan’s hand shot out and grabbed the notebook, lifting it up to examine it with exaggerated confusion.

“What is this garbage?”

“Trying to look smart. Please give it back,” Eli said quietly, his voice barely above a whisper. Speaking to Dylan, to anyone really, took enormous effort. The words felt heavy in his mouth, difficult to push past the barrier of his lips.

“Please give it back,” Dylan mimicked in a high-pitched voice, causing his friends to laugh from across the cafeteria.

“Come on, Turner. Use your words.”

“Oh, wait. You can’t, can you? Because your brain doesn’t work right.”

The bell rang just then, its sharp electronic tone cutting through the tension. Dylan dropped the notebook back on the table, making sure to crumple one of the pages in the process.

“See you in math class, Slowpoke,” he said, walking away with his friends trailing behind like loyal puppies.

Eli carefully smoothed out the crumpled page, his fingers gentle as if he were handling something precious. The equation was still legible, the logic still sound, but the disruption to his routine, the invasion of his space, left him feeling unsettled and raw.

He packed up his materials slowly, making sure everything was in its proper place in his backpack. Each item had a specific pocket, a specific orientation. The organization helped him feel like he had some control in a world that often felt chaotic and unpredictable.

The hallways were crowded with students rushing to their next classes. Eli waited by his locker, counting to 60 before joining the flow. He learned that waiting exactly one minute after the bell meant the hallways were still busy enough that he could blend in, but not so packed that he’d have to deal with unexpected physical contact. He walked close to the wall, his hand occasionally brushing against the painted concrete blocks for orientation.

Math class was in room 237, second floor, third door on the right, past the water fountain. Eli had memorized the route on the first day of school, counting the steps, noting the landmarks: 17 steps to the stairwell, 22 steps up, 43 steps to the classroom door. The predictability of it calmed his nerves slightly.

Ms. Alvarez was already at the front of the classroom when he entered, writing today’s objectives on the whiteboard in her neat, careful handwriting. She was young for a teacher, maybe late 20s, with thick black hair pulled back in a ponytail and warm brown eyes that seemed to see more than most adults bothered to notice. She wore a purple cardigan today over a white blouse and small silver earrings that caught the light when she moved.

“Good afternoon, Eli,” she said warmly as he passed her desk. She always greeted him specifically, never grouping him in with a general “good afternoon class.” It was a small gesture, but it meant something to him.

Eli nodded in response and made his way to his usual seat: third row, second seat from the window, not too far front to draw attention, not too far back to seem disengaged. The desk was scratched and worn, initials of previous students carved into its surface, but it was his desk, the one he’d sat at since the first day of school months ago.

Other students filed in, the noise level increasing with each arrival. Dylan entered with his usual fanfare, high-fiving friends and making jokes loud enough for everyone to hear. He made a point of walking past Eli’s desk, accidentally knocking his pencil to the floor.

“Oops,” Dylan said with false sincerity. “Hey Turner, since you’re so slow at everything else, maybe you can slowly pick that up.”

A few students laughed. Others looked away uncomfortably. Sarah, a quiet girl who sat two rows over, actually rolled her eyes at Dylan’s behavior, though she didn’t say anything.

Eli bent down to retrieve his pencil, his movements deliberate and calm, giving no satisfaction of a reaction.

“That’s enough, Dylan,” Ms. Alvarez said sharply, not even looking up from her preparation.

“Take your seat.” Dylan shrugged and sauntered to his desk in the back row where he could continue his commentary with minimal supervision.

Ms. Alvarez finished writing on the board and turned to face the class.

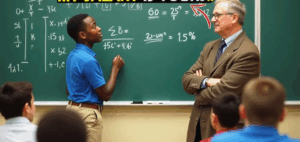

“All right, everyone, settle down,” she called out as the second bell rang. “Today, we’re working on quadratic equations. I know some of you find this challenging, but remember, there’s always more than one way to solve a problem.”

She began the lesson with an explanation of the standard form, writing ax2+bx+c=0 on the board and explaining each component.

Eli already knew this, had known it for years. He’d taught himself quadratics when he was 11, finding an old algebra textbook at a yard sale and working through it during the summer his father was first diagnosed with cancer. Math had been an escape then, a world where problems had solutions, where everything followed logical rules.

“Let’s start with a volunteer,” Ms. Alvarez said after her explanation, writing a new equation on the board: 2×2+8x+6=0. “Who can tell me the first step in solving this?”

Several hands shot up immediately. Dylan was among them. His arm stretched high with the confidence of someone who never doubted his place in the world.

“Dylan,” Ms. Alvarez called, though Eli could see the slight hesitation in her expression.

“You factor it.”

“Obviously,” Dylan said with a smirk, glancing around to make sure everyone appreciated his quick response.

“Good start. Can you show us how?”

Dylan strutted to the board, picked up the marker with a flourish that seemed practiced, and began writing. He started confidently enough, but Eli could see the error coming before Dylan even made it. He was going to forget to factor out the common factor first, which would make the rest of his work unnecessarily complicated.

Sure enough, halfway through, Dylan’s work became muddled. He’d written 2×2+8x+6=2x×2x+3, which wasn’t even close to correct. The class waited in awkward silence as Dylan stared at his work, clearly knowing something was wrong but not sure what.

“Actually,” Ms. Alvarez said gently, “let’s think about this step by step. What’s the first thing we should look for?”

“I don’t know,” Dylan said defensively. “This is stupid anyway. When are we ever going to use this in real life?”

As he returned to his seat, he made sure to knock against Eli’s desk again, harder this time. Eli’s carefully arranged pencils rolled across the surface.

“Eli,” Ms. Alvarez said suddenly, “Would you like to try the problem?”

The room seemed to hold its breath. Every head turned to look at him. Eli felt the weight of their stares like physical pressure on his skin, his chest tightened, his breathing becoming shallow.

He could solve it in seconds, could show three different methods, explain why Dylan’s approach failed, and demonstrate the elegant beauty of mathematical relationships. But the thought of standing up there, feeling all those eyes on him, having to speak loud enough for everyone to hear—it was almost paralyzing.

“I’ll… I’ll try,” he said quietly, his voice barely above a whisper.

He stood up slowly, each movement careful and measured. The walk to the board felt endless, like moving through thick syrup. The fluorescent lights seemed too bright, the whispers of his classmates too loud.

When he picked up the marker, his hand trembled slightly—not from nerves about the math, but from the overwhelming sensory input and social pressure.

“Come on, Turner. We don’t have all day,” Dylan called out from the back. “Is your brain still buffering? Still loading? Maybe try turning it off and on again.”

The laughter that followed was sharper this time. More students joined in. Someone made a computer error sound. Another student whispered something about special ed, just loud enough for Eli to hear.

His hand froze mid-equation. The numbers that usually comforted him suddenly felt distant, unreachable behind the wall of mockery and sensory overload.

“Dylan Morrison, principal’s office. Now,” Ms. Alvarez commanded, her usually gentle voice carrying an edge of steel that made several students sit up straighter.

“It was just a joke,” Dylan protested. But he was already gathering his things under Ms. Alvarez’s unwavering stare.

“God, nobody can take a joke anymore.”

“Office now,” Ms. Alvarez repeated, pointing to the door.

That was the moment Dylan passed Eli at the board. He whispered just loud enough for him to hear, “Freak, you’re going to regret this.”

After Dylan left, the room fell into an uncomfortable silence.

Eli stood at the board, marker still in hand, the incomplete equation staring back at him. His hand shook more visibly now, the marker making small clicking sounds against the board.

Ms. Alvarez walked over and stood beside him, not touching, just present, her cardigan giving off a faint scent of vanilla that was oddly comforting.

“Take your time, Eli,” she said softly, her voice meant just for him. “Or if you’d prefer, you can finish it at your seat. Whatever makes you comfortable.”

Eli nodded gratefully and practically fled back to his desk.

Once seated in his familiar spot with his things arranged just so around him, the fog in his mind began to clear.

He completed the problem in his notebook in under 30 seconds. But he used a method that wouldn’t be taught until advanced algebra.

First, he factored out the common factor of 2, getting 2(x2+4x+3)=0. Then he factored the quadratic in parentheses to get 2(x+1)(x+3)=0, making the solutions x=−1 and x=−3.

But he didn’t stop there. Below that, he showed two alternative methods: completing the square and using the quadratic formula. Each one executed with perfect precision.

The mathematical symbols flowed from his pencil like music notes in a symphony only he could hear.

Ms. Alvarez walked by his desk during independent work time and her eyes widened when she saw his notebook. She leaned down, careful not to get too close. She’d learned that Eli preferred a certain amount of personal space and whispered, “This is beautiful work, Eli. You see math differently than others. That’s not a weakness. It’s a gift, a rare one.”

She paused, seeming to consider something.

“Can you stay after class for just a moment? I have something I’d like to discuss with you.”

Eli nodded, though the prospect of staying after class, of breaking his routine, made his stomach clinch with anxiety.

The rest of the class passed in a blur of practice problems that Eli completed in the first five minutes, leaving him 25 minutes to work on more interesting problems in the margins of his notebook. He derived a proof for the quadratic formula itself, something that wouldn’t typically be covered until pre-calculus, and then began exploring what would happen with quadratics in complex number systems.

When the bell rang, students rushed out, eager for their next class or, for the lucky eighth graders with last period study hall, to start their semi-freedom.

Eli packed up slowly, methodically, each item going into its designated spot in his backpack.

“Eli,” Ms. Alvarez said once they were alone, “I’ve been watching your work all semester. What you do with numbers—it’s extraordinary.”

Eli focused on the floor tiles, counting the black specks in the white laminate: seven in the tile nearest his foot, twelve in the next one.

“There’s a competition,” Ms. Alvarez continued. “The state math Olympiad. It’s in three weeks. I’d like to nominate you to represent Jefferson Middle School.”

Eli’s head snapped up, his eyes wide with something between terror and surprise.

“I can’t,” he said immediately.

“Why not?”

“Because… because everyone will be watching. And Dylan…” Eli stopped, unable to articulate the crushing weight of social expectation, the exhaustion of being perceived, the fear of exposure.

“I understand it’s scary,” Ms. Alvarez said gently. “But Eli, you have a gift that deserves to be shared. You don’t have to hide it.”

“They’ll laugh,” Eli whispered, his voice cracking slightly.

“Maybe some will,” Ms. Alvarez admitted. “But others might be inspired. Others might see what I see—a brilliant young mathematician who happens to process the world differently. That’s not something to be ashamed of.”

She wrote something on a sticky note and handed it to him.

“This is my cell phone number. Talk to your mom about it tonight. The decision is yours, but I want you to know that I’ll support you either way. And Eli, I’ll make sure Dylan doesn’t interfere. You have my word on that.”

The walk home felt longer than usual. Eli’s mind churned through possibilities, probabilities, potential outcomes.

The math Olympiad meant standing in front of judges, other students, parents. It meant being seen, really seen, not just as the weird, quiet kid, but as someone attempting something significant.

The thought made his chest tight with anxiety.

The apartment building came into view. Its faded red brick familiar and comforting.

Mrs. Rodriguez was sitting on the front stoop watching her grandchildren play. She waved at Eli and he gave a small wave back, appreciating that she never tried to force conversation.

Inside, the apartment was quiet and dim, the afternoon sun filtering through old curtains his mother had sewn herself from fabric bought on clearance. The smell of coffee lingered from his mom’s morning routine, mixing with the faint scent of the lavender candle she always kept burning. His father had given it to her on their last anniversary before he got sick, and she’d been carefully burning it in small increments ever since, making it last.

Eli dropped his backpack by the door in its designated spot, exactly six inches from the wall, parallel to the door frame, and went straight to the kitchen.

The note was where it always was, held to the refrigerator by a magnet shaped like a sunflower that his father had bought at a gas station during their last family road trip.

“Leftover pasta in the fridge. Home by 7. Love you, baby. Mom.”

Below that, she’d added, “P.S. Ms. Alvarez called. We’ll talk tonight.”

So, she already knew.

Eli felt a mixture of relief and apprehension.

He heated up the pasta exactly two minutes in the microwave, stirring once at the one-minute mark, and took it to his room.

His bedroom was the one space in the world that truly felt like his.

The walls were covered with mathematical proofs and theorems, some copied from textbooks in his precise handwriting, others original work that would have impressed college professors.

Above his desk, he taped up a picture of Srinivasa Ramanujan, the self-taught Indian mathematician who revolutionized number theory despite having almost no formal training. Next to it was a photo of Katherine Johnson, the NASA mathematician whose calculations had been critical to the success of US space flights.

His desk, a scratched wooden hand-me-down from a neighbor who was moving, was organized with military precision. Pencils lined up by size in a repurposed coffee mug, erasers stacked in a small tower, papers sorted into color-coded folders he’d bought at the dollar store.

The organization wasn’t just preference; it was necessity. When the world felt chaotic and overwhelming, having this one space where everything was exactly where it should be helped him breathe.

He pulled out a stack of grocery receipts from the drawer, their backs blank and waiting. Paper was a luxury they couldn’t always afford, but Danielle always saved receipts for him, knowing he needed surfaces to work out his thoughts. She’d even started shopping at three different stores to maximize the number of receipts she could collect, though she’d never told Eli this.

Tonight’s problem was from a number theory textbook he’d borrowed from the library. The maximum checkout was three weeks, and he was already on his second renewal.

The problem dealt with the Goldbach conjecture, one of the oldest unsolved problems in mathematics: every even integer greater than two could be expressed as the sum of two primes.

It had been verified for numbers up to enormous values but never proven universally.

Eli wasn’t trying to prove it. He wasn’t that ambitious. But he was exploring patterns in the prime pairs, looking for relationships that others might have missed.

His pencil flew across the receipt paper, numbers flowing like water.

This was where he felt most himself, where the confusion and cruelty of the social world faded away, leaving only the pure logic of mathematics.

Time ceased to exist when he was working like this.

The angle of sunlight through his window changed. The sounds from the street outside shifted from after-school chaos to dinnertime quiet.

But Eli noticed none of it.

He was deep in the world of numbers. Where everything made sense, where he wasn’t weird or slow or different. He was just another explorer in the infinite landscape of mathematics.

The sound of keys in the lock pulled him from his trance. He glanced at the clock. 7:23 p.m.

His mom was late, which usually meant the dinner rush had been busier than expected or someone had called in sick and she’d had to cover.

He quickly gathered his receipts, organizing them carefully in chronological order of when he’d solved each part, and tucked them into a folder labeled “Gold Explorations.”

The conversation with his mother had gone better than Eli expected.

Danielle hadn’t pushed or pressured, just held his hand across their small kitchen table and said, “Baby, you’ve been hiding your light under a bushel your whole life. Maybe it’s time to let it shine.”

By morning, Eli had made his decision.

He would compete.

Three weeks passed in a blur of preparation.

Mr. Patel, the retired professor Ms. Alvarez had mentioned, turned out to be a gentle man in his 70s with white hair and kind eyes behind thick glasses.

He met with Eli every afternoon at the public library—not to teach him math, as Eli needed no help there—but to prepare him for the experience of competition. They practiced working problems while Mr. Patel made deliberate distractions, helping Eli build his focus against external chaos.

Now, standing outside Jefferson Middle School’s gymnasium on a Saturday morning, Eli felt his breakfast threatening to come back up.

The familiar space had been transformed.

What was usually filled with basketball hoops and bleachers now held rows of individual desks, each one precisely spaced, each with a small placard bearing a competitor’s name and school.

A massive digital scoreboard had been installed on the far wall, currently dark but waiting to display rankings and scores for everyone to see.

The parking lot was filling with cars far nicer than anything usually seen at Jefferson Middle.

Eli watched from beside his mother’s ancient Honda Civic as families emerged from SUVs and luxury sedans. Parents in expensive clothes ushered children who looked like miniature professionals, some wearing blazers with school crests, others in pressed khakis and polo shirts with logos from prestigious private schools.

Eli looked down at himself: dark jeans from Walmart, a plain blue t-shirt, and his trusty navy hoodie.

The hoodie that had been his armor for three years now felt thin and inadequate against the weight of these stares.

Danielle noticed his discomfort and squeezed his shoulder gently.

“You belong here,” she said firmly. “Don’t let anyone make you think otherwise.”

They walked toward the entrance together, Eli counting his steps as always.

“Three from the car to the sidewalk, 47 from the sidewalk to the main doors.”

Inside, the gymnasium was buzzing with nervous energy.

Parents clustered in groups, their conversations a low hum of college admissions, tutoring programs, and academic camps that cost more than Danielle made in three months.

The registration table was staffed by parent volunteers wearing matching purple t-shirts with “State Math Olympiad” printed in gold letters.

The woman checking Eli in had perfectly manicured nails and a smile that didn’t quite reach her eyes when she saw his school name.

“Jefferson Middle,” she said, her tone suggesting she’d bitten into something sour.

“Table 32. Parents must remain in the designated viewing area.”

She handed Eli a competitor packet and pointed vaguely toward the sea of desks.

Danielle walked him as far as she was allowed, then stopped at the rope barrier separating the competition floor from the spectator section.

“I’ll be right here,” she promised.

Every second, Eli nodded and made his way through the maze of desks, trying not to notice the looks from other competitors. Some were curious, others dismissive, a few almost pitying.

Table 32 was in the middle section—not prestigious enough for the front rows reserved for previous winners and top seeds, but not banished to the back with the first-time schools. Nobody expected to place that high.

He sat down carefully, arranging his materials just so.

Three pencils perfectly sharpened to the same length. Two erasers, one pink, one white. His lucky calculator—the one his father had used in college—held together with tape on one corner where it had been dropped years ago.

The desk was different from the ones at school, newer, more stable, with a smooth surface unmarked by years of student graffiti.

“You’re from Jefferson?”

The voice startled him.

A girl stood beside his desk, maybe 15, with long black hair pulled into a perfect ponytail and wearing a blazer with Preston Academy embroidered on the pocket.

This was Lena Chararma.

Eli recognized her from the program packet.

Three-time regional champion headed to the national competition last year.

“Yes,” Eli managed, his voice barely audible.

Lena studied him with dark, intelligent eyes.

“I’ve heard about you. Ms. Alvarez called my coach, asked for advice about preparing someone special. You’re the one who solves college-level problems for fun.”

Eli didn’t know how to respond to that, so he just nodded slightly.

“Interesting,” Lena said, and for once, the word didn’t sound like an insult. “Good luck today. You’ll need it.”

She paused, then added more quietly, “The problems here aren’t like school math. They’re designed to break you. Don’t let them.”

She walked away to her own desk, table three, front row, defending champion position, leaving Eli to process the interaction.

It was the first time another student at one of these things had talked to him like an equal rather than a curiosity.

More competitors filed in, the noise level rising steadily.

Eli pulled his hood up, trying to create a bubble of calm in the chaos.

He could hear fragments of conversation around him: discussions of math camps and private tutors, complaints about problems from previous years, speculation about what topics might appear.

One boy at a nearby table was literally reviewing flashcards with formulas as if this were a history test requiring memorization rather than problem solving.

Then he heard a familiar unwelcome voice.

“No way. Turner’s actually here.”

Dylan Morrison was standing by the viewing area rope, having come to watch the competition for extra credit in Ms. Alvarez’s class.

Several other Jefferson Middle students were with him, including Marcus and some others who regularly participated in Eli’s daily humiliation.

“Yo, Turner,” Dylan called out loud enough for half the gym to hear. “Try not to freeze up when they start the timer.”

“Oh, wait. Your brain probably needs extra time to buffer, right?”

Several people turned to look. Some competitors snickered at the comment.

Eli felt heat rise to his face, his hands starting to do the small flapping motion he tried so hard to control in public.

He pressed them flat against the desk, counting prime numbers in his head: 2, 3, 5, 7, 13.

“That’s enough,” a stern voice said.

Mr. Patel appeared beside Dylan wearing one of the purple volunteer shirts.

“Young man, you need to keep your voice down or leave.”

Dylan smirked but lowered his voice to a level that wouldn’t get him ejected.

He and his friends found seats in the bleachers where they could maintain a clear view of Eli.

Their phones were already out to record what they clearly expected to be a disaster.

“Competitors, please take your seats. The gymnasium’s PA system will begin in five minutes.”

Eli closed his eyes, running through the calming exercises Mr. Patel had taught him.

Breathe in for four counts. Hold for four. Out for four.

Visualize the problems as shapes, patterns, friends rather than enemies.

Remember that numbers don’t judge. Don’t laugh. Don’t care about your clothes or your skin color or the way your brain works differently.

Welcome to the state math Olympiad.

Dr. Patricia Hoffman, from the State University Mathematics Department, stepped to the microphone.

“Today’s competition will consist of four rounds, each progressively more difficult. Scores will be displayed on the board after each round.

“No calculators for the first two rounds. Partial credit for showing work. Time limits strictly enforced.”

Eli had heard all this before from Mr. Patel, but hearing it officially made his stomach clench tighter.

“Round one will begin now. You have 45 minutes. Good luck.”

The volunteers distributed papers face down on each desk.

Eli stared at the blank back of the page, his heart hammering so hard he was sure everyone could hear it.

Around him, competitors sat poised, pencils ready.

When the buzzer sounded, the synchronized sound of papers flipping filled the gym.

Eli turned his paper over and read the first problem, then read it again.

The words seemed to swim on the page, the letters rearranging themselves into meaningless patterns.

This wasn’t like the practice problems Mr. Patel had given him. This was different, harder, designed to trick and trap.

From the bleachers, he could hear Dylan’s stage whisper.

“Look, he’s already stuck on the first one.”

Eli forced himself to breathe, to focus.

He read the problem a third time, and suddenly, like a key turning a lock, it clicked.

It wasn’t actually that hard.

It was just disguised to look hard.

They’d wrapped a relatively simple number theory problem in complex language and unnecessary information.

Once he saw through the camouflage, the solution was almost elegant.

His pencil began to move slowly at first, then with increasing confidence.

He showed each step of his work clearly, the way Mr. Patel had insisted, even though he could see the answer immediately.

The second problem was geometry, using triangles within triangles to create an optical illusion that hid the true relationships.

Eli drew additional lines, creating a proof that revealed the hidden pattern.

By the third problem, he’d found his rhythm.

The gymnasium noise faded to background static.

Dylan’s voice became irrelevant white noise.

There were only the problems in him, dancing together in mathematical harmony.

His unconventional approaches—visualizing numbers as colors and shapes, seeing equations as musical patterns—gave him perspectives that traditional training might have obscured.

Problem four nearly stopped him.

It was a combinatoric question involving probability that seemed to have no clear entry point.

Eli stared at it for five precious minutes, his confidence wavering.

Then he remembered something from the online forums, a discussion with a professor in Germany about non-standard approaches to counting problems.

He tried that method and, like magic, the problem unraveled.

“Fifteen minutes remaining,” Dr. Hoffman announced.

Eli looked down at his paper.

He’d completed six of eight problems with strong starts on the other two.

Around him, he could hear erasers working frantically, pencils scratching, occasional sighs of frustration.

One girl two tables over was crying quietly.

A boy in a Preston Academy blazer had his head in his hands.

He returned to problem seven, which dealt with sequences and series.

The standard approach would take too long.

But if he applied a technique from calculus, something definitely not expected for middle school students, he could solve it in half the time.

He did so carefully, explaining his reasoning so the judges would understand he wasn’t just guessing.

Five minutes.

Problem eight would have to remain partially unsolved.

Eli wrote what he knew, outlined the approach he would take given more time, and made an educated guess at the final answer based on the patterns he had identified.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was better than leaving it blank.

“Time, pencils down.”

The collective exhale from 63 competitors was audible.

Volunteers moved efficiently through the rows, collecting papers.

Eli sat back, suddenly exhausted, as if he’d run a marathon rather than sat at a desk for 45 minutes.

His hand was shaking slightly, and he could feel sweat making his t-shirt stick to his back.

“There will be a 15-minute break while we score round one,” Dr. Hoffman announced. “Refreshments are available in the lobby.”

Eli didn’t move.

He knew if he stood up now, if he had to navigate the crowd and the social dynamics of the break, he’d never make it back for round two.

Instead, he pulled out his water bottle, filled exactly to the line he’d marked with permanent marker, and took small measured sips.

“That was brutal,” someone said behind him.

Two competitors from a suburban school were comparing notes.

“Did you get problem four?”

“I tried using the standard formula, but gave me a negative probability, which makes no sense.”

“Same. I think it was a trick question.”

Eli wanted to tell them about the non-standard approach to explain how the problem was actually beautiful once you saw it correctly, but the words wouldn’t come. They never did with strangers, especially in situations like this.

Danielle appeared at the rope barrier as close as she was allowed to come.

She caught Eli’s eye and mouthed, “You okay?”

He nodded, managing a small smile.

She blew him a kiss and returned to her seat where she’d been sitting rigidly for the entire round. Her hands clasped so tightly her knuckles were white.

The 15 minutes felt both endless and far too short.

Then volunteers were distributing new papers and round two was beginning.

These problems were harder, as promised.

They required not just mathematical knowledge, but creative thinking, the ability to see connections between seemingly unrelated concepts.

Eli attacked the problems with newfound confidence.

The first round had shown him he belonged here, that his different way of thinking was an asset rather than a liability.

When a problem about prime numbers appeared, he actually smiled.

This was his territory, the landscape he’d been exploring on grocery receipts for years.

His pencil flew across the page, proofs flowing like water.

He used techniques he’d learned from online discussions, approaches he developed himself during long nights when sleep wouldn’t come and only numbers could quiet his racing mind.

One problem required thinking about infinity.

Most students would struggle with the abstract concept.

But Eli had been contemplating infinity since he was 10, trying to understand where his father had gone when the cancer finally won.

“Look at him go,” someone whispered nearby.

“He’s already on problem five.”

This time the comment wasn’t mocking. It was impressed, maybe even a little worried.

Eli didn’t let it distract him.

He was in the zone now, that rare state where his autism wasn’t a barrier but a superpower, allowing him to hyperfocus with an intensity that neurotypical minds couldn’t match.

Round two ended with Eli completing all eight problems, though he wasn’t entirely confident about his answer to problem six.

During the break, volunteers posted scores on the digital board.

The gymnasium went quiet as everyone searched for their placement.

Eli had to read the list three times before he believed what he was seeing.

Lena Chararma, Preston Academy, 87 points.

Eli Turner, Jefferson Middle, 85 points.

David Chun, Riverside Prep, 83 points.

Second place.

Out of 63 competitors, including students from schools with specialized math programs and expensive tutors, he was in second place.

A murmur rippled through the crowd.

People were turning to look at him, really look at him for the first time—not with pity or mockery, but with genuine surprise and growing respect.

In the bleachers, Dylan’s mouth was hanging open, his phone forgotten in his hand.

“No way,” Marcus said loud enough to hear.

“There’s no way Turner is in second.”

The scores were verified by three independent judges.

Mr. Patel said mildly, having positioned himself near the Jefferson Middle contingent, “There’s no mistake.”

Samantha was there, too.

Eli noticed for the first time.

She must have come with the extra credit group.

But instead of sitting with Dylan and his crew, she was on the opposite side of the bleachers.

When she caught Eli’s eye, she smiled and gave him a small thumbs up.

He found himself smiling back, the first genuine smile he’d shown in public in months.

“Congratulations,” a voice said beside him.

Lena had walked over from her table.

“Your solution to problem four was elegant. I overheard the judges discussing it. They hadn’t seen that approach before.”

“Thank you,” Eli managed, his voice stronger than usual.

Something about

Lena’s matter-of-fact acceptance made talking easier. “The next two rounds are different,” she warned quietly. “They’re not just about solving problems. They’re about handling pressure. Some people crack when they see their name on the board, when they realize everyone’s watching. Don’t be one of them.”

She returned to her seat, leaving Eli to ponder her words. As if to illustrate her point, the boy who’d been in third place after the first round was now at the bathroom, apparently being sick from nerves. A girl who’d been in the top ten was crying at her desk while her parents hugged her. Danielle caught Eli’s attention from the viewing area. She was crying too, but they were tears of joy and pride. She pressed her hand to her heart and then pointed at him—their secret signal from when he was little, meaning I love you, without words.

Round three began after lunch, which Eli didn’t eat. His stomach was too knotted, his mind too focused. The problems were, as Lena had warned, brutal. They combined multiple concepts, required seeing patterns that weren’t immediately obvious, demanded not just knowledge, but intuition.

One problem seemed impossible until Eli realized it was actually about music theory disguised as mathematics—the relationships between frequencies in harmonic sequences.

Another required understanding fractals, which he’d studied on his own after becoming fascinated with the Mandelbrot set.

Each problem was a puzzle wrapped in an enigma designed to find not just who knew math, but who truly understood it.

Halfway through the round, something shifted in the gymnasium’s atmosphere.

Word had somehow spread beyond the competition.

Local news crews were setting up cameras near the entrance.

A reporter was interviewing Dr. Hoffman about the surprise competitor from Jefferson Middle.

Eli tried to ignore it all to maintain his bubble of focus, but the weight of observation was becoming oppressive.

His hands started flapping again—the stimming motion he couldn’t always control when overwhelmed.

He forced them still, but that made his legs start bouncing instead.

Numbers began swimming on the page.

His breathing became shallow and quick.

Then he heard it—a soft, rhythmic tapping.

He looked up to see Samantha at the barrier tapping out a pattern on the rope.

It was the same pattern she taught him during their library study sessions.

A grounding technique she used for her own anxiety.

“Tul, top, pulp,” over and over, steady as a heartbeat.

Eli matched his breathing to the pattern.

His hands stilled.

The numbers came back into focus.

He returned to the problems with renewed determination, solving two more before time was called.

He’d managed six of eight this time, but they were solid solutions.

Each one showing the kind of deep mathematical understanding that separated true mathematicians from people who were just good at arithmetic.

During the break before the final round, the scores were updated.

Eli Turner, Jefferson Middle, 239 points.

Lena Chararma, Preston Academy, 239 points.

David Chun, Riverside Prep, 220 points.

Tied for first.

The gymnasium erupted in excited chatter.

This never happened at states.

There was always a clear leader by round three.

The judges huddled in conference, apparently discussing how to handle the unprecedented situation.

Dylan and his friends were silent now, their mockery replaced by stunned disbelief.

A woman with a television camera on her shoulder approached Eli’s desk.

“Can we get a quick interview? This is an amazing story.”

“Unknown student from an underfunded school challenging the established.”

“No,” Eli said, the word coming out harsher than intended.

“Please, no,” Mr. Patel intervened, gently but firmly moving the camera crew away.

“The young man needs to focus on the final round. Perhaps after.”

But the damage was done.

Eli could feel everyone watching him now.

The weight of their expectations, their curiosity, their disbelief pressed down on him like a physical force.

His safe bubble of mathematical focus was shattered.

The gym felt too bright, too loud, too full of people who saw him as a story rather than a person.

The final round problems were distributed.

Eli’s hands shook as he turned the paper over.

The first problem might as well have been written in ancient Sumerian for all the sense it made to his overwhelmed brain.

He tried to breathe to find his calm, but panic was building in his chest like a storm.

From the bleachers, he heard Dylan’s voice deliberately pitched to carry.

“Look, he’s choking. Told you he couldn’t handle real pressure.”

That should have made things worse.

But instead, something crystallized in Eli’s mind.

Dylan was wrong.

Dylan had always been wrong.

Every cruel comment, every mockery, every attempt to make Eli feel small and broken—they were all wrong.

Because Eli wasn’t broken.

His brain just worked differently.

And that difference was exactly what allowed him to see solutions others missed.

He thought about his father, who’d spent his last months doing math puzzles with Eli in the hospital, saying, “When they doubt you, let the answer speak for itself.”

He thought about his mother working double shifts but still finding energy to encourage his gift.

He thought about Ms. Alvarez who saw potential where others saw problems.

He thought about Mr. Patel, patient and kind, teaching him to navigate a world that wasn’t built for minds like his.

He even thought about Samantha, brave enough to offer friendship when it would have been easier to stay silent.

They all believed in him.

More importantly, for the first time in his life, Eli believed in himself.

He picked up his pencil and really looked at the first problem.

It was complex, yes, but complexity was just another pattern waiting to be understood.

He began breaking it down piece by piece, like taking apart a clock to see how the gears fit together.

The solution emerged slowly, each step building on the last.

The second problem was about graph theory, something most middle schoolers never encountered.

But Eli had explored online, debating with university students about optimal pathways and node connections.

He drew the graph, identified the critical points, and found the elegant solution hiding beneath the complicated surface.

By problem three, he was back in his flow state.

The gym faded away.

Dylan’s voice became meaningless noise.

The cameras didn’t exist.

There were only numbers, patterns, and the beautiful logic that connected them all.

Fifteen minutes remaining.

Eli had completed four of the five problems.

The fifth was a monster—a proof that required connecting concepts from algebra, geometry, and number theory in ways that would challenge graduate students.

But as he stared at it, something clicked.

He’d seen something similar in a paper by Terence Tao, the famous mathematician.

Not the same problem, but the same underlying structure.

He began writing his proof—unconventional, but rigorous.

He used mathematical induction in a way that would make traditionalists cringe but was undeniably valid.

He connected seemingly unrelated theorems, building bridges between mathematical islands that most people didn’t even know existed.

Five minutes.

His proof wasn’t quite complete, but the structure was there.

The logic sound.

He added a final line explaining where the proof would go given more time, showing he understood not just the mechanics but the deeper mathematical truth.

“Time, pencils down.”

This time, the silence that followed was profound.

Everyone seemed to sense that something significant had just happened.

Eli sat back, completely drained.

His pencil rolled off the desk, but he didn’t have the energy to pick it up.

The wait for final scores felt eternal.

Judges huddled over papers, occasionally calling each other over to look at particular solutions.

Dr. Hoffman was examining one paper with particular intensity, occasionally shaking her head in what looked like amazement.

Finally, after 40 minutes that felt like 40 hours, Dr. Hoffman took the microphone.

“Before we announce the final scores, I want to say something.

“In 20 years of running this competition, I’ve rarely seen such innovative problem solving.

“Some of today’s solutions show not just mathematical knowledge, but true mathematical thinking—the kind that advances our field.”

She paused, building tension.

“In third place, with 310 points, David Chun from Riverside Prep.”

Polite applause.

David looked pleased with his placement.

“In second place, with 347 points, Lena Chararma from Preston Academy.”

Lena smiled, apparently unsurprised.

She’d won three years in a row and knew what her score meant.

“And in first place, with 351 points, representing Jefferson Middle School, Eli Turner.”

The gymnasium exploded.

Not just polite applause, but genuine cheering, mostly from people who didn’t even know Eli but recognized they’d witnessed something special.

Danielle was sobbing openly, her hands pressed to her face.

Samantha was on her feet, clapping so hard her hands must have hurt.

Even some of the Preston Academy parents were applauding, recognizing exceptional achievement when they saw it.

But the sweetest sound was the silence from Dylan’s section of the bleachers.

He sat frozen, his phone hanging limply in his hand, his worldview shattered by undeniable proof that he’d been wrong about everything.

The scoreboard flickered as the updated rankings appeared, and a collective gasp rippled through the gymnasium.

Eli Turner’s name glowed in digital amber right beside Lena Chararma’s, both showing 239 points.

Tied for first place.

The unknown boy from the underfunded school had caught up to the three-time regional champion.

Cameras clicked frantically as photographers rushed to capture the historic moment.

Eli felt each flash like a physical assault on his senses.

The bright lights left floating spots in his vision.

His hands began their familiar flapping motion before he forced them still, pressing his palms flat against his desk.

The numbers on his scratch paper blurred as his breathing became shallow and rapid.

“This is unprecedented,” Dr. Hoffman announced, her voice carrying a mixture of surprise and excitement.

“In 15 years of state math Olympiad competitions, we’ve never had a tie going into the final rounds.”

From the bleachers, Dylan Morrison’s voice cut through the murmur of amazement.

“No way that’s real. He must have cheated somehow.”

But even Dylan’s cronies weren’t laughing anymore.

The evidence was undeniable.

Three rounds, three different sets of judges, all confirming that Eli Turner from Jefferson Middle School was matching the best young mathematician in the state point for point.

Danielle sat rigid in the viewing area.

Her hands clasped so tightly her knuckles had gone white.

She’d taken the afternoon off from the diner, losing money they desperately needed.

But she wouldn’t have missed this for anything.

During the break, her phone had buzzed with a text that made her stomach drop.

The landlord demanding this month’s rent by Friday or eviction proceedings would begin.

Three days.

They had three days to come up with money they didn’t have.

She deleted the message quickly, not wanting even the possibility of Eli seeing it.

Her boy had enough pressure without knowing their housing situation was hanging by a thread.

“Competitors, please return to your seats for round four,” Dr. Hoffman announced.

“As we have a tie for first place, this round will be particularly significant.”

Eli made his way back to his desk, noticing how different the atmosphere had become.

Competitors who had dismissed him earlier now watched him with weary respect.

Parents whispered and pointed.

A group of teachers from Preston Academy huddled together, apparently discussing how Jefferson Middle had produced such talent without any advanced programs.

As he sat down, a younger competitor at the adjacent desk, probably a sixth grader competing for the first time, leaned over slightly.

“That was amazing,” the kid whispered. “You’re like a legend already.”

Before Eli could respond, something clattered onto his desk.

A pencil had rolled off the desk behind him, landing precisely on his paper.

Then another, then several sheets of blank paper somehow scattered across his workspace, messing up his carefully arranged materials.

“Oh, sorry,” said a boy Eli didn’t recognize, wearing a Riverside Prep blazer.

“Total accident! So clumsy of me.”

The boy’s eyes darted toward the bleachers where Dylan sat, and Eli understood immediately.

Dylan had found someone to do his dirty work, probably promising something in return.

Money, popularity, protection from bullying at their own school.

Eli’s anxiety spiked.

His materials were in disarray.

His pencils were out of alignment.

His scratch paper was crumpled.

The chaos made his skin crawl, made his thoughts scatter like startled birds.

He could feel the meltdown building, the overwhelming urge to flee, to hide, to escape this place where everything was wrong and loud and hostile.

Then he heard it—a soft rhythmic tapping.

“Tul, top, p-top.”

He looked up to see Samantha at the barrier, her hand moving in the pattern they practiced during their library sessions.

It was her grounding technique, the one she used for her own anxiety when her stutter got bad.

The one she taught him when words became too difficult.

Eli matched his breathing to the pattern.

In and out, hold, out.

His racing heart began to slow.

With deliberate movements, he reorganized his materials.

Three pencils aligned perfectly.

Scratch paper smoothed and stacked.

Calculator positioned at exactly the right angle.

By the time the fourth round problems were distributed, his workspace was restored to order and with it a fragile sense of calm.

“Begin,” Dr. Hoffman announced.

The first problem hit Eli like a slap.

It was complex beyond anything from the previous rounds, involving multiple mathematical disciplines woven together in a way that seemed designed to confuse rather than challenge.

For a moment, panic threatened to resurface.

Then he remembered something his father had said during one of their last hospital visits.

“When a problem seems impossible, Eli, break it into pieces. Solve each piece, then see how they fit together.”

Eli began dissecting the problem, identifying each component.

There was number theory here, yes, but also graph theory, a touch of topology, even some abstract algebra.

Individually, each piece was manageable.

The challenge was seeing how they interconnected around him.

He could hear other competitors struggling.

Someone two rows over was crying quietly.

A girl from Preston Academy had put her head down on her desk.

Even Lena, he noticed with a quick glance, was frowning in concentration, her usual confidence replaced by intense focus.

Problem two was even worse.

It seemed to be about probability, but the more Eli worked on it, the more he realized it was actually about patterns in chaos theory.

This wasn’t middle school math or even high school math.

This was the kind of problem discussed in graduate seminars.

But Eli had encountered chaos theory online in a discussion with a professor from MIT about weather prediction models.

He applied those same principles here and slowly the solution emerged.

Halfway through the round, the pressure in the room had become almost tangible.

The temperature had risen from so many stressed bodies in one space.

Someone had opened the emergency exit for air, letting in the sound of traffic and distant sirens.

Parents in the viewing area were no longer chatting.

They watched their children with expressions of concern and helpless anxiety.

Danielle’s phone buzzed again.

Another text from the landlord, this time with a photo of an eviction notice he was preparing to file.

She turned the phone face down, her jaw clenched.

Not now.

She couldn’t deal with this now.

Eli needed her to be strong, to be present, to believe in him without the shadow of their financial crisis showing on her face.

“Twenty minutes remaining,” Dr. Hoffman announced.

Eli had completed three of the six problems with partial solutions for two others.

The sixth problem remained untouched, a monster of a question that seemed to require knowledge of mathematical concepts he’d never encountered.

He stared at it, his mind racing through everything he’d learned online and off, searching for any connection, any foothold.

Then something clicked.

The problem looked impossible because it was written to obscure its true nature.

It was actually a logic puzzle disguised as advanced mathematics.

Once he saw through the camouflage, the solution was almost elegant in its simplicity.

His pencil flew across the paper, sketching out a proof that would have made his online mathematics friends proud.

Five minutes.

Eli looked at his work.

Five problems solved completely, one partially.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was solid.

More importantly, his solutions showed deep understanding, not just mechanical problem solving.

He’d used techniques from multiple disciplines, drawn connections that weren’t immediately obvious, demonstrated the kind of mathematical thinking that separated true mathematicians from people who were just good at arithmetic.

“Time, pencils down.”

The collective exhale from 63 competitors sounded like a deflating balloon.

Eli’s hand was cramping from writing so intensely, and his shirt was damp with sweat despite the cool air from the open door.

He looked up to find numerous eyes on him.

Competitors trying to gauge how he’d done based on his expression.

During the break, volunteers updated the scoreboard.

The gymnasium fell silent as the numbers appeared.

Eli Turner, Jefferson Middle, 341 points.

Lena Chararma, Preston Academy, 338 points.

David Chun, Riverside Prep, 310 points.

First place alone at the top.

The murmur that ran through the crowd was different this time.

Not surprise, but recognition.

This wasn’t a fluke or luck.

Eli Turner was genuinely, undeniably, brilliantly talented.

“No,” Dylan said loudly from the bleachers.

“No way. This is impossible. He’s autistic. He can’t even talk properly. There’s no way he’s beating Lena Sharma.”

“Mr. Morrison,” Vice Principal Roberts, who had been observing from a back corner, stood up sharply.

“One more outburst and you’ll be removed from the premises.”

But the damage was done.

Dylan had said out loud what some people were thinking.

How could this kid, this different kid, this Black autistic kid from the poor side of town be winning?

It challenged too many assumptions, broke too many stereotypes.

Eli felt the weight of those stares, those whispered conversations, those disbelieving expressions.

His chest tightened.

The gymnasium suddenly felt too small, too hot, too full of people who saw him as a curiosity rather than a person.

Eli needed to get out to find somewhere quiet, too.

Lena had walked over to his desk.

She didn’t look angry about losing her lead.

Instead, she looked impressed.

“That solution to problem four,” she said quietly, “using chaos theory—that was brilliant.

I’ve been doing competition math for six years, and I’ve never seen anyone approach a problem like that.”

“You understood it?” Eli asked, his voice barely audible.

“I’m going to be studying it for weeks,” Lena admitted.

“You don’t just solve problems, do you? You see them differently, like they’re alive or something.”

She paused, then added even more quietly.

“Don’t let them get to you.

Dylan Morrison, the parents who think you don’t belong here, any of them.

You’ve already proven them wrong.

The last round, it’s going to be public on the big screen.

Everyone watching every stroke of your pencil.

It’s designed to break people, but I don’t think you’re breakable.”

The gymnasium had been transformed for the final round.

A massive projection screen had been set up at the front with special cameras positioned over each of the top five competitors’ desks.

Every pencil stroke would be visible to the entire audience.

It was mathematical performance as spectator sport.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Dr. Hoffman announced, “for the final round, the top five competitors will solve problems in real time with their work projected for all to see.

This tests not just mathematical ability, but also grace under extreme pressure.”

Eli’s desk was now in the front row, positioned between Lena and David Shun.

Behind them sat the fourth and fifth place competitors, both from expensive preparatory schools.

The remaining competitors had become audience members, their competition over but their interest intense.

The crowd had grown, too.

Word had spread beyond the competition.

Local news crews had arrived, setting up cameras along the sides of the gymnasium.

Parents, who had been casual observers, were now recording everything on their phones.

The atmosphere was electric with anticipation.

Danielle had managed to move to the front row of the viewing area.

Despite some grumbling from parents who’d been sitting there earlier, she ignored their disapproving looks, focusing entirely on Eli.

She could see the tension in his shoulders, the way his hands trembled slightly as he arranged his materials for the fifth time.

“The final round consists of five problems,” Dr. Hoffman explained.

“Each competitor will have their work projected in real time.

You’ll have one hour.

The problems increase in difficulty with the final problem worth double points.”

She paused dramatically.

“Additionally, if we still have a tie after this round, we have prepared a special tiebreaker problem from the International Mathematical Olympiad Archives—something that has stumped even seasoned mathematicians.”

Eli closed his eyes, running through Mr. Patel’s calming exercises.

Breathe in for four.

Hold for four.

Out for four.

Visualize the problems as friends, not enemies.

Remember that mathematics doesn’t judge, doesn’t laugh, doesn’t care about anything except logic and truth.

“Competitors ready?” Dr. Hoffman asked.

“Begin.”

The first problem appeared on Eli’s paper and simultaneously on the giant screen, his desk camera capturing every detail.

For a horrifying moment, his mind went completely blank.

The entire gymnasium was watching him think, watching him struggle, waiting for him to either triumph or fail spectacularly.

From the bleachers, Dylan’s voice carried despite the supposed silence.

“Look, he’s freezing already.”

This time, it wasn’t Vice Principal Roberts who responded.

It was Samantha standing up in the middle of the crowd, her voice clear despite her usual stutter.

“Shut up, Dylan.

Just shut up and let him work.”

The gymnasium went silent, shocked by the outburst from the usually quiet girl.

Samantha’s face went red, but she remained standing, staring defiantly at Dylan.

A few people actually applauded her courage.

That moment of unexpected support broke through Eli’s mental freeze.

Samantha had stood up for him in public despite her own anxiety.

The least he could do was solve this problem.

He looked at it again and suddenly saw it clearly.

It was a number theory problem disguised as geometry.

Once he recognized the true nature, his pencil began moving.

On the big screen, the audience watched a solution unfold.

Unconventional, creative, beautiful in its elegance.

The second problem was pure algebra, but with a twist that would trap anyone following standard methods.

Eli had encountered something similar in a discussion with Vector King forum members about non-standard mathematics.

He applied those principles here.

His solution flowing across the page in neat lines of logic.

By the third problem, Eli had found his rhythm.

The gymnasium, the cameras, the audience—they all faded into background static.

There were only the problems in him, engaged in a familiar dance.

His unusual visualization methods—seeing numbers as colors, equations as musical patterns—gave him perspectives that traditional training might have obscured.

On the screen, the audience could see his work in real time, and whispers of amazement rippled through the crowd.

He wasn’t just solving the problems.

He was approaching them in ways that made professors in the audience lean forward with interest.

“Is he using Ramanujan’s theorem?” someone whispered.

“That’s graduate level mathematical thinking. How does a middle schooler even know about that?”

The fourth problem nearly stopped him.

It was a combinatorics question of such complexity that even writing out all the conditions took half a page.

Eli stared at it, his mind racing through possibilities.

Then he remembered something—a paper he’d read online about game theory and its applications to combinatorial problems.

He began applying those principles, building a solution that was unorthodox but undeniably correct.

Beside him, Lena was working with fierce concentration.

Her own solutions appearing on the adjacent screen.

She was keeping pace with him point for point, their different approaches to the same problems creating a fascinating contrast for the mathematically literate in the audience.

“Fifteen minutes remaining,” Dr. Hoffman announced.

The fifth problem was the monster worth double points and designed to separate the exceptional from the merely excellent.

It required synthesizing concepts from across multiple mathematical disciplines, seeing connections that weren’t immediately apparent, and having the courage to pursue unconventional approaches.

Eli read it once, twice, three times.

It seemed impossible even for him.

He could hear shuffling from the audience, sense their anticipation on the screen.

His hesitation was visible to everyone.

Then something his father once said echoed in his mind.

“When everyone expects you to fail, you’ve got nothing to lose by trying something extraordinary.”

Eli began writing.

“Not a standard solution, but something entirely different.”

He was building a proof using mathematical induction combined with graph theory, creating bridges between concepts that most people didn’t even realize were connected.

It was the kind of solution that would either be brilliant or completely wrong.

There was no middle ground.

His pencil moved faster now, racing against time.

The proof grew more complex, more beautiful, more audacious with each line.

In the audience, several mathematics professors were on their feet trying to follow his logic on the big screen.

Five minutes.

Eli’s proof wasn’t complete, but the structure was there.

The logic sound.

He added a final paragraph explaining where the proof would go given more time, demonstrating that he understood not just the mechanics, but the deeper mathematical truth underlying the problem.

“Time. Pencils down.”

The gymnasium erupted in applause before Dr. Hoffman could even call for quiet.

It wasn’t just polite clapping.

It was genuine appreciation for having witnessed something special.

Even some of the Preston Academy parents who’d been skeptical of this unknown competitor were applauding.

Eli sat back, completely drained.

His hand was shaking from the intense writing, and he felt like he’d run a marathon rather than sat at a desk for an hour.

On the screens, his solutions remained displayed.

Five different windows into a mind that worked unlike any other.

The judges huddled for what felt like hours but was actually only 20 minutes.

They called each other over repeatedly, pointing at specific solutions, having animated discussions about scoring.

Dr. Hoffman was examining Eli’s final proof with particular intensity, occasionally shaking her head in what looked like amazement.

Finally, she took the microphone.

“Before we announce the final scores, I need to say something.

In 20 years of running this competition, I’ve rarely seen such innovative problem solving.

The approaches we’ve witnessed today, particularly in the final round, demonstrate not just mathematical knowledge, but true mathematical thinking—the kind that advances our field.”

She paused, building tension.

“The scores for the final round alone were exceptionally close.

The difference between first and second place came down to the partial credit awarded for the final problem.”

The scoreboard flickered to life.

Final round scores:

Eli Turner: 93 points.

Lena Chararma: 91 points.

David Chun: 82 points.

Which means…

Dr. Hoffman continued, “Our final standings for the state math Olympiad are…”

The main scoreboard updated.

Final standings:

Eli Turner, Jefferson Middle, 434 points.

Lena Chararma, Preston Academy, 429 points.

David Chun, Riverside Prep, 392 points.

The gymnasium exploded.

Not just applause, but actual cheering.

People on their feet, cameras flashing like strobe lights.

Eli sat frozen, unable to process what had just happened.

He’d won.

He’d actually won.

Danielle was crying openly, not caring who saw.

Samantha was jumping up and down, clapping so hard her hands must have hurt.

Mr. Patel had a satisfied smile like he’d known this would happen all along.

Ms. Alvarez was hugging other Jefferson Middle teachers.

All of them crying and laughing simultaneously.

And in the bleachers, Dylan Morrison sat in stunned silence.

His phone hanging limply in his hand.

His entire worldview shattered by undeniable proof that everything he believed about Eli Turner was wrong.

Lena was the first to reach Eli, extending her hand with a genuine smile.

“That final proof was genius,” she said simply.

“You’ve changed how I think about mathematics.”

As more people crowded around to congratulate him, Eli felt overwhelmed but also something else—proud.

For the first time in his life, he’d shown the world who he really was, and the world had recognized his worth.

The aftermath of Eli’s victory was immediate and overwhelming.

As he stood frozen at his desk, still processing what had just happened, Dr. Hoffman approached with a wireless microphone and a warm smile.

Behind her, the camera crew that Mr. Patel had earlier turned away was setting up again.

Their lens pointed directly at him like the eye of some massive unblinking creature.

“Eli, that was an extraordinary performance,” Dr. Hoffman said, her voice carrying through the gymnasium speakers.

“Would you mind sharing a few words about your experience today?”

Eli looked at the microphone like it might bite him.

His mouth opened, closed, opened again.

No words came.

The gymnasium, which had been buzzing with excitement, began to quiet as people waited for him to speak.

The silence stretched, becoming uncomfortable, then painful.

Someone coughed.

A baby cried in the back row of bleachers.

Dylan’s laugh, sharp and mocking, cut through the quiet.

“I…” Eli started, his voice cracking.

He cleared his throat, tried again.

“I just… I like math.”

A few people chuckled, not unkindly.

Dr. Hoffman’s smile grew softer, more understanding.

She was about to speak, perhaps to rescue him from the moment.

When Mr. Patel stepped forward, his purple volunteer shirt slightly rumpled from the long day.

“If I may,” he said gently, taking the microphone with practiced ease.

“What Eli has accomplished today goes beyond just liking math.

This young man has been contributing to advanced mathematical discussions for over two years, though most of you wouldn’t know it.”

He paused, glancing at Eli as if asking permission.

Eli, still overwhelmed but trusting Mr. Patel, gave a small nod.

His hands had started their familiar flapping motion, but for once, he didn’t try to stop them.

“Online, in mathematical forums where professors and graduate students gather to discuss complex problems, Eli is known by another name: Vector King.”

The reaction was immediate and dramatic.

Several people in the audience gasped.

A man in a University of State sweatshirt actually stood up, his mouth hanging open.

Even Lena’s composed expression cracked, showing genuine surprise.

Near the back, a woman dropped her phone, the clatter echoing in the sudden silence.

“Vector King!” the man in the university sweatshirt called out, his voice carrying disbelief and excitement.

“The Vector King who solved the modified Collatz conjecture problem that stumped our entire graduate seminar.”

Mr. Patel nodded, a hint of pride in his expression.

“The very same.

For two years, some of the brightest mathematical minds in the world have been unknowingly learning from a 14-year-old boy from Jefferson Middle School.”

The camera crew was practically vibrating with excitement.

The reporter, a young woman with perfectly styled hair and an ambitious gleam in her eye, pushed forward through the crowd.

This was no longer just a feel-good story about an underdog winning a math competition.

This was something bigger, more significant.

The kind of story that could make a career.

“Eli, is this true? You’re really Vector King?”

She thrust the microphone toward him, nearly hitting him in the face.

Eli managed to nod, his hands flapping more intensely now.

The revelation of his online identity felt like being stripped naked in front of everyone.

That had been his safe space where he could be valued purely for his mind without any of the social complications that came with face-to-face interaction.

Now, even that sanctuary had been breached.

“This is incredible,” the reporter continued, her words coming rapid-fire.

“A teenager from an underfunded school secretly helping solve university-level problems.

How did you learn all this?

Do you have special tutoring?

What do your parents think?

Have you been contacted by universities?”

The questions came too fast, overlapping, creating a wall of sound that made Eli’s head spin.

He took a step back, then another, his breathing becoming shallow and quick.

The gymnasium lights seemed to brighten, the crowd noise intensified, everything becoming too much.

“That’s enough,” Danielle’s voice cut through the chaos like a blade.

She had made her way through the crowd and now stood beside her son, not touching him.

She knew he wouldn’t want that with all these people watching, but positioning herself as a shield between him and the aggressive reporter.

“My son needs space.”

“Mrs. Turner, just a few questions.”

“I said enough,” Danielle’s tone brooked no argument.

Carrying the authority of someone who’d faced down worse than ambitious reporters.

“You want to talk to us? You go through proper channels right now.

My boy needs to breathe.”

She turned to Eli, her voice dropping to the gentle tone she used when he was overwhelmed.

“Count with me, baby. Prime numbers like we practiced together quietly.”

They counted: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11.

The familiar pattern calmed Eli’s racing heart.

Gave his mind something to focus on besides the chaos around him.

From across the gymnasium, a woman in an expensive suit had been watching the scene with interest.

She wore a badge identifying her as Dr. Sarah Blackwood from the Mathematical Acceleration Institute, one of the most prestigious summer programs in the country.

She approached slowly, respectfully, waiting for Eli to regain his composure.

“Mrs. Turner, Mr. Turner,” she said, her voice calm and professional.

“When you’re ready, I’d very much like to speak with you both about an opportunity.”

Meanwhile, the online mathematics community was exploding with the news on mathforums.net where Vector King was legendary.

The revelation sparked hundreds of posts within minutes.

“Vector King is 14 years old. This explains why his solutions always had such unique perspectives.”

“I’m a PhD candidate, and this kid helped me understand apolgy. I’m rethinking my life choices.”

“Jefferson Middle School doesn’t even have an advanced math program. How is this possible?”

Back in the gymnasium, Dr. Blackwood had managed to guide Eli and Danielle to a quieter corner away from the cameras and crowds.

She pulled out a folder from her briefcase, extracting an official-looking document embossed with gold lettering.

“Eli,” she said, addressing him directly with respect, not the condescension many adults used with teenagers.

“I’ve been watching your performance today with great interest, even more so now that I know you’re Vector King.

We’ve actually been trying to identify and contact you for months.”

She opened the folder revealing program brochures filled with images of students working on whiteboards covered in equations, attending lectures in beautiful auditoriums, collaborating in state-of-the-art facilities.

“I’d like to offer you a full scholarship to our summer program.

It’s an eight-week intensive where you would work with some of the brightest young mathematical minds in the country, mentored by leading mathematicians, including two Fields Medal winners.”

Danielle’s eyes widened.

She knew about the program.

She’d looked it up once, dreaming of possibilities for Eli before seeing the $20,000 price tag.

“A full scholarship,” Dr. Blackwood confirmed.

“Tuition, room and board, materials, even a stipend for personal expenses.