How One Apache’s “Crazy” Footprint Trick Exposed a Hidden Japanese Base in the Jungle

The Footprint That Broke Japan’s Best Jungle Deception (New Guinea, May 15, 1943)

May 15th, 1943—New Guinea.

The jungle canopy turned the afternoon sun into scattered coins of gold, flashing briefly on wet leaves before vanishing again into green darkness. The air was thick enough to drink. Every step on the muddy trail sounded wrong—too loud, too wet, too final—as if the forest itself recorded everything that moved through it.

Sergeant James Whitehorse crouched low and held his hand above a shallow dent in the mud.

To the five soldiers behind him, it looked like nothing. A rain mark. A worn spot. A mistake of the earth. After seventeen patrols that had ended the same way—back to camp with empty hands and the familiar ache of failure—no one expected this one to be different. Intelligence had insisted for months that a Japanese supply depot existed somewhere in the Finisterre Range: a hidden node feeding the enemy’s jungle war. But every mile of this place looked identical: roots, vines, shadow, and silence.

Whitehorse didn’t see “nothing.”

He saw a lie.

And one tiny flaw in that lie was about to unravel four months of Japanese deception—deception so sophisticated it had fooled reconnaissance aircraft, ground patrols, and even local informants.

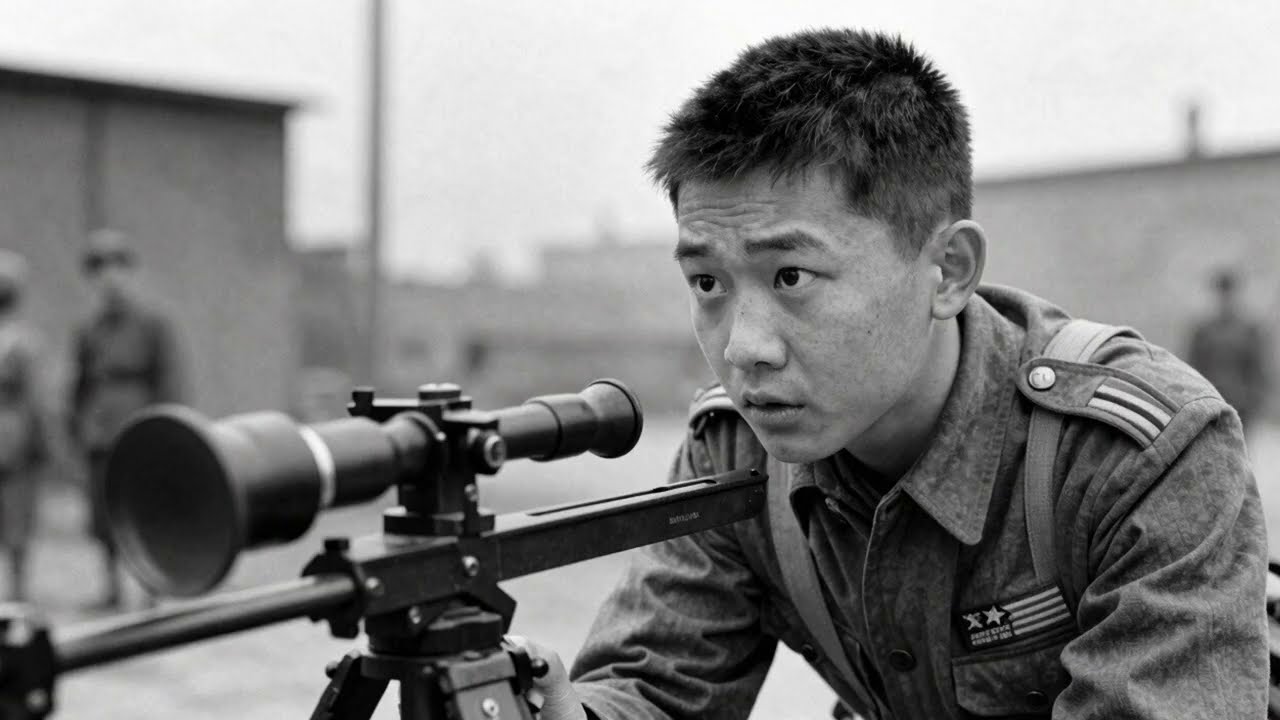

A Tracker Recruited for What the Jungle Couldn’t Hide

Whitehorse had arrived in the Southwest Pacific only six weeks earlier, one of a small group of Native American soldiers recruited specifically because the Army had finally admitted something uncomfortable:

In jungle warfare, technology wasn’t enough. Maps lied. Aerial photos lied. Even radios lied.

But the ground—if you knew how to listen—couldn’t.

Whitehorse was the son of a cattle rancher from the Fort Apache Reservation in Arizona. He’d grown up learning to read the earth the way other boys learned to read books. His grandfather—called by the Apache something that translates roughly as he who sees what others miss—had drilled one belief into him: every living thing leaves a story behind. Bent grass, shifted pebbles, scuffed bark, soil packed in the wrong direction—each was a sentence.

The war in the Pacific had turned concealment into an art form. Japanese forces were masters of camouflage. In New Guinea’s rainforests, they built underground facilities capable of housing hundreds of soldiers, invisible from the air and nearly impossible to find on foot. They didn’t just hide; they designed what the enemy would see.

Allied intelligence had intercepted radio traffic suggesting a major supply depot existed in a twenty-square-mile box of jungle—nearly impenetrable. Twenty-three patrols in fourteen weeks found nothing.

Captain Richard Morrison had led nine of them personally.

A West Point graduate, Morrison had studied the clean geometry of warfare: lines of advance, supply routes, decisive terrain. But nothing in his education prepared him for an enemy that didn’t “defend” so much as dissolve into the landscape. He watched Whitehorse with a mix of hope and skepticism—the same look a drowning man gives a rope he isn’t sure will hold.

Whitehorse stayed motionless for almost two minutes, eyes scanning the forest floor in a pattern that seemed random to everyone else.

Then he stood and faced Morrison with an expression that held certainty—and something close to amusement.

“Someone walked backward through here,” he said. “Stepping into existing prints to hide their passage.”

Morrison felt his pulse jump. “Backward?”

Whitehorse nodded. “And they made a mistake.”

The Mistake That No One Was Supposed to See

Whitehorse knelt again and waved Morrison down beside him. In the mud, the footprint was faint—but the sergeant treated it like evidence in a courtroom.

“When a person walks normally,” he explained, “the heel strikes first. That’s where the deepest impression is—back of the print.”

He pointed. Then shifted his finger forward.

“When someone walks backward trying to step into tracks,” he continued, “weight shifts. The toe becomes the deepest point because that’s what they’re watching to place their foot.”

The print showed toe-first pressure—yet it “pointed” as if the person had been walking away from the mountains toward Allied positions.

It was a staged message: Traffic flows out, not in. Nothing important is up there. Stop looking.

Private Tommy Chen, a Chinese American soldier from San Francisco who served as interpreter, leaned in close as if he expected the mud to explain itself. He’d grown up in a city where tracking meant following streetcars and headlights. What Whitehorse described sounded almost supernatural.

“How can you be sure it’s not just… how he walks?” Chen asked.

Whitehorse didn’t argue. He walked forward along the trail and, over the next thirty yards, found six more prints. Each carried the same signature: reversed pressure points. Not one or two—an intentional pattern.

“No one walks like this naturally,” Whitehorse said. “This is work. Someone is trying very hard to make you believe the wrong direction.”

Morrison ordered the patrol to spread out in a defensive perimeter while he radioed battalion headquarters.

Lieutenant Colonel Patrick Hayes, the battalion commander, listened with cautious interest. Hayes was a veteran of North Africa. He had learned the hard way that war punishes anyone who ignores unusual intelligence. He authorized Morrison to follow the trail but insisted on reinforcements: another squad and a radio team.

While they waited, Whitehorse kept reading the forest—and found something worse.

Vegetation along the trail had been trimmed in ways that looked natural at first glance, but created clear sight lines at regular intervals. Not a random animal path. Not accidental. A maintained corridor designed to appear abandoned while being used routinely.

Corporal David Sullivan, a farm boy from Iowa, frowned. “So what does that mean?”

“It means they’re not hiding,” Whitehorse said. “They’re performing.”

They weren’t merely concealing a base. They were actively shaping Allied behavior.

Following the Lie Deeper into the Mountains

By the time reinforcements arrived three hours later, Whitehorse had identified a dozen more backward prints and mapped what he believed were multiple routes converging deeper inland.

Sergeant Robert Tanaka—Japanese American, attached as translator—studied Whitehorse’s observations with rising excitement. Tanaka had interrogated prisoners and studied Japanese doctrine. This level of deception, he said, matched special engineering units trained to construct and protect hidden facilities.

The expanded patrol moved inland as daylight bled toward evening. Whitehorse led them along a route that seemed to violate common sense: following “tracks” that suggested movement away from the interior—only to use that contradiction as proof they should go in.

The jungle thickened. The ground turned treacherous. Morrison worried they were being pulled into a trap. But every time doubt rose, Whitehorse found another clue: a cut tree repositioned to block an obvious path; rocks placed to make a route appear impassable; vegetation patterns just a little too uniform to be wild.

That night they camped in a small clearing Whitehorse declared safe because it lacked the “managed” feel of the deception corridor. Men slept lightly, listening to the jungle’s endless noise and the deeper quiet underneath it—the quiet that meant they were close.

Dawn brought rain—hard tropical sheets that turned the forest floor into streams.

Morrison feared the tracks would wash away.

Whitehorse wasn’t worried. “I’m not following footprints anymore,” he said. “I’m following the deception.”

Once you understood the trick, the signs multiplied.

The First Hard Evidence: A Crate That Was Planted Wrong on Purpose

Shortly after noon on the second day, Private First Class Michael O’Brien—ex-construction worker from Boston—almost tripped over a piece of metal half-buried in mud. It was part of a Japanese ammunition crate, markings still visible.

But Whitehorse’s attention wasn’t on the metal. It was on its placement.

Someone had buried it here, away from any logical supply route, positioned to imply Japanese movement to the east rather than the west—another false arrow for Allied patrols.

Tanaka examined the markings and identified the contents: 75mm shells, ammunition associated with Type 88 anti-aircraft guns.

That mattered because intelligence had reported no Japanese anti-aircraft positions in this region.

If they were hauling that ammunition, they were protecting something worth protecting.

The Garden That Pretended to Be Wild

On the third day, the backward footprints were gone, erased by rain. Whitehorse navigated by the same invisible handwriting: unnatural order disguised as chaos.

Then they found a garden.

A clearing fifty feet across, edible plants growing in neat rows—except someone had tried to make it look wild. Vines woven through crops. Dead leaves scattered strategically. Weeds allowed to grow in “natural” clusters that were anything but natural.

It was camouflage by theater design: make it messy so it looks untouched.

Hayes ordered extreme caution. A concealed garden meant they were near an occupied position—possibly within a few hundred yards. Two more platoons were on the way, but hours out.

The patrol moved forward with weapons ready, nerves stretched tight.

Whitehorse whispered to Morrison, “We’re being channeled. Guided. Someone wants us to walk a certain line.”

The question was whether the Japanese knew they were here—or whether this was simply how the deception system worked.

The answer arrived in a scream.

The Trap That Was Too Old to Be a Trap

Sergeant First Class William Drake stepped on what looked like solid ground and dropped into a concealed pit. His cry cut off as he hit eight feet below—onto sharpened bamboo stakes.

The patrol froze, expecting gunfire.

None came.

Drake was hauled out bleeding, badly lacerated but alive. Whitehorse examined the pit and said something that changed the shape of the mission:

“This trap is old,” he said. “Months. Not maintained.”

The bamboo showed weathering inconsistent with active defenses. Someone had dug it and then—astonishingly—stopped caring.

Morrison asked what that meant.

“It means they’ve been here long enough to get comfortable,” Whitehorse said. “They don’t expect anyone to come this deep.”

Tanaka added another detail: the pit had been dug with precision tools. Straight edges. Uniform depth. Engineers.

Morrison made a hard choice. He would take Drake back to meet reinforcements and guide them in. Whitehorse would continue forward with a small recon element—five men—moving slowly and reporting every thirty minutes.

Dangerous. But Morrison trusted Whitehorse to avoid detection.

The Breath of the Mountain

The recon team moved like ghosts. They found more gardens. A stream subtly diverted so water flow pointed away from the interior. And then, near evening, O’Brien spotted something almost invisible: a shimmer above a cluster of rocks, like heat haze.

But this wasn’t heat. It was airflow.

Whitehorse approached and felt the stones with his fingertips. Real rock—arranged around a metal pipe protruding a few inches, capped with something shaped and painted to resemble stone.

A ventilation shaft.

Within twenty minutes they found four more, distributed to disperse airflow and avoid detection. Whatever lay beneath them was large enough to need serious ventilation—and sophisticated enough to hide it.

Whitehorse radioed Morrison. Reinforcements were closing. Hayes authorized a full company-strength probe with artillery on standby.

Find the entrance. Do not enter until overwhelming force is ready.

The Hillside That Opened Like a Door

They searched until darkness, spiraling outward from the vents, finding nothing. So they made an observation post overlooking the area.

That night, Corporal Sullivan noticed something wrong with a hillside two hundred yards away: vegetation shifted slightly—too localized for wind, too deliberate for nature.

Whitehorse studied it through binoculars for ten minutes.

“The hillside is artificial,” he said. “A camouflage structure.”

But it wasn’t just hiding the entrance.

It was the entrance.

Shortly after midnight Morrison and the main force arrived. Engineers and intelligence officers moved into position. Radio silence. No lights. Everyone watched the hillside as dawn seeped gray through the trees.

Then the impossible happened.

The hillside opened—smoothly, almost casually. A section of “earth” covered in vegetation swung outward on concealed hinges, revealing a tunnel mouth wide enough to drive a truck through.

Two Japanese soldiers stepped out and stretched like men starting a routine day.

Hayes waited, counting personnel, watching patterns. Seventeen soldiers entered or left over the next hours—relaxed, unalarmed.

Then a column of civilians emerged: fourteen men and women, thin and exhausted, carrying bundles of roots and vegetation under loose supervision.

Tanaka’s voice tightened. “Local villagers,” he said. “Forced labor.”

That changed everything.

Hayes decided to wait until civilians returned, then seal the entrance and force surrender—avoiding a direct assault that might kill the very people they needed to save.

At 0500 the next morning, loudspeakers broadcast a surrender demand in Japanese: surrounded by overwhelming force, resistance futile, civilians will not be harmed.

Fifteen minutes of silence.

Then the camouflaged door opened, and a Japanese officer stepped out with hands raised.

Lieutenant Teeshi Yamamoto, commander of the depot. He wanted terms for civilian safety first.

Negotiations took three hours. Civilians were released. Japanese soldiers would disarm and exit in order.

What came out of that tunnel stunned everyone: not thirty or forty men, but ninety-seven personnel—engineers, communications specialists, supply troops, security—operating underground for seven months.

Inside, the facility ran more than four hundred feet into the mountain: chambers carved from living rock, stockpiles sufficient to support a regiment for months, a radio center capable of reaching far across the theater, and maps of other hidden sites.

In Yamamoto’s journal, intelligence officers found the final sting:

He had recorded seventeen Allied patrols that had come within a quarter mile of the entrance—watched them pass, confident in his deception.

One entry described the backward footprints explicitly.

He hadn’t anticipated meeting someone trained to read the lie itself.

Because no deception is perfect.

Somewhere, somehow, the earth keeps a receipt.

And on May 15th, 1943, one faint footprint—wrong in exactly the right way—brought a hidden mountain to life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1GXgETwxLG4