The air in Chicago was crisp, tinged with the golden hues of autumn. Michael Jordan, now 61, moved through Washington Park with a quiet grace that belied his legendary status. He wore a black puffer jacket, jeans, and a cap pulled low—an attempt at anonymity that never quite worked in the city he once electrified. But today, Michael wasn’t seeking crowds or cameras. He needed a moment of peace, a chance to reflect on a life lived above the rim and beyond expectation.

As he sat on a weathered bench beside a small pond, his mind drifted to memories of roaring crowds, game-winning shots, and the weight of six championship rings. Yet, as the wind nipped at his cheeks, Michael’s thoughts were interrupted by the sight of a man sitting on the grass some yards away. The man’s clothes were tattered, his face marked by hardship and cold. He huddled beneath a thin blanket, shivering, with a battered backpack and a makeshift shelter of cardboard propped against a tree.

Most people would have looked away. But Michael, remembering his own humble beginnings in Wilmington, North Carolina, felt a pull he couldn’t ignore. He stood, adjusted his cap, and approached the man, his imposing frame casting a long shadow across the grass.

“Hey man,” Michael said softly, his North Carolina accent warm and familiar. “You look like you could use some help. It’s getting cold out here.”

The man looked up, his eyes weary but kind, a faint scar running across his cheek. “I’m fine, sir,” he replied, his voice rough with fatigue. “Just trying to stay warm.”

Michael noticed the man’s hands—calloused and dirty, but with a small tattoo on his forearm, partly hidden by the sleeve of his jacket. It was the unmistakable image of a man in midair, dunking a basketball, the number 23 inked beside it. Michael’s heart skipped a beat. He recognized the pose instantly: his own iconic free-throw line dunk from the 1987 Slam Dunk Contest.

“That’s a nice tattoo,” Michael said, gesturing to the man’s arm. “Looks familiar.”

The man glanced at his tattoo, a faint smile crossing his face. “Yeah,” he said, “it’s you, isn’t it? Michael Jordan. I’m a big fan—or I was.”

Michael knelt beside him, extending a hand. “I’m Michael,” he said. “What’s your name, brother?”

The man shook his hand, his grip weak but sincere. “Terrence. Terrence Brooks.”

Without hesitation, Michael shrugged off his jacket and handed it to Terrence. “Here. You need this more than I do.”

Terrence took the jacket with trembling hands, his eyes filling with tears. “Thank you, Mr. Jordan,” he whispered. “You don’t know what this means. I—I don’t deserve this.”

Michael shook his head. “Everyone deserves a little help,” he said. “But I gotta ask—why that tattoo? What’s the story behind it?”

Terrence gazed at the pond, the wind ruffling what remained of his hair. “I got this tattoo in 1987,” he began. “I was twenty, just a kid from Chicago. I was a ball boy at the All-Star Weekend that year. I watched you take off from that free-throw line—like you were flying. I’d never seen anything like it. The whole place went crazy. I felt like I was part of something bigger.”

He paused, voice trembling. “I was good at basketball, too. Got a scholarship to a small college because of it. That dunk, that moment—it gave me hope. Made me believe I could make it, too.”

Michael listened, his heart swelling with pride but also a growing sadness.

“But things didn’t work out,” Terrence continued. “I got injured my sophomore year—tore my ACL. Lost my scholarship, had to drop out. I tried to keep going, worked odd jobs, but life kept knocking me down. My wife left. I lost my house. I’ve been on the streets for five years now. But I kept this tattoo, Mr. Jordan. It reminds me of a time when I believed in myself—because of you.”

Michael’s throat tightened as he remembered that dunk, the moment that changed his life—and, he realized now, Terrence’s too. “I’m so sorry, Terrence,” he said, his voice thick with emotion. “I had no idea. But you’re not done, man. You’re still here, still fighting. That means something.”

Terrence wiped his eyes, managing a small smile. “You really think so?”

“I know so,” Michael replied, determination flashing in his eyes. “And I’m going to help you get back on your feet. That’s a promise.”

Michael didn’t stop at giving Terrence his jacket. He called a friend who ran a local shelter and arranged for Terrence to have a warm bed, meals, and access to job training programs. Through his foundation, he set up a small fund to cover Terrence’s expenses for the next six months, giving him the stability he needed to rebuild.

Over the following months, Terrence transformed. He got a job at a local community center, coaching kids in basketball—teaching them the lessons he’d learned from watching Michael all those years ago. Michael visited often, bringing Terrence to a Hornets game and even inviting him to a Bulls alumni event, where Terrence reconnected with the sport that once gave him hope.

“Michael Jordan didn’t just give me a jacket,” Terrence often told the kids he coached. “He gave me my life back.”

For Michael, the encounter with Terrence was a turning point. It reminded him of the power of his legacy—the way a single moment could ripple through someone’s life, even decades later. It deepened his commitment to helping those in need, ensuring that his legacy wasn’t just about championships, but about the lives he touched off the court.

In 2025, Michael continued his work with the Hornets and his foundation, carrying Terrence’s story in his heart as a reminder of why he did what he did. Terrence Brooks became a mentor to at-risk youth in Chicago, crediting Michael for showing him the true meaning of resilience.

“Michael Jordan was my hero in 1987,” Terrence said, “and now he’s my hero in 2024.”

This story isn’t just about a kind gesture in a park. It’s about the power of connection, the strength of redemption, and the way a single moment from the past can come back to change everything. Michael Jordan didn’t just help a homeless man—he rediscovered a piece of his own legacy, and turned a moment of hardship into a lifetime of hope.

Trump claims a Michael Jordan tattoo is evidence of Venezuelan gang membership

An internal Trump administration document claims that having a Michael Jordan “Jumpman” tattoo and wearing “high-end urban street wear” makes you a likely member of the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua (TDA) gang. The document was recently made public in a federal court case. The case is contesting the Trump administration’s deportations of over 200 Venezuelan noncitizens it deems to be TDA members, without any due process, to a notorious prison in El Salvador.

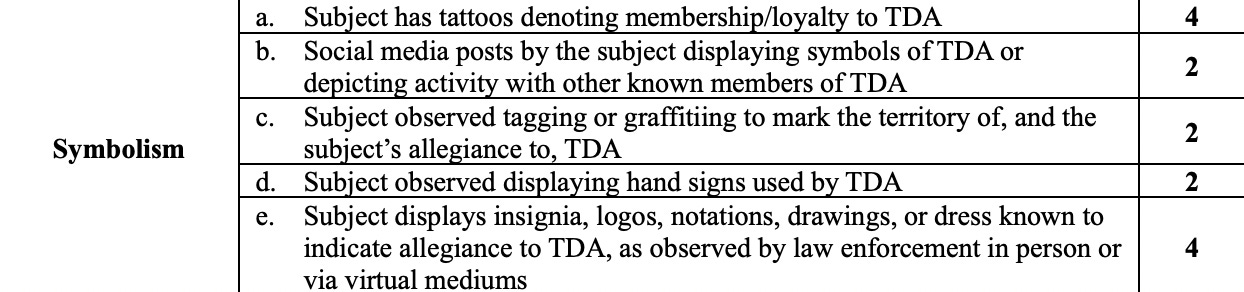

The document, titled “ALIEN ENEMY VALIDATION GUIDE,” creates a point system to determine whether a Venezuelan over 14 years of age is a TDA member. Anyone scoring eight points or higher “are validated as members of TDA.” Those scoring six or seven can be deemed members of TDA depending on the “totality of the facts.”

Some of the scoring system is based on court records. For example, being found by a court to have violated “federal or state law…for activity related to TDA” is worth 10 points. Any court document “identifying the subject as a member of TDA” is worth five points.

But people can also be assigned points based on “Symbolism.” Someone with “tattoos denoting membership/loyalty to TDA” is assigned four points.

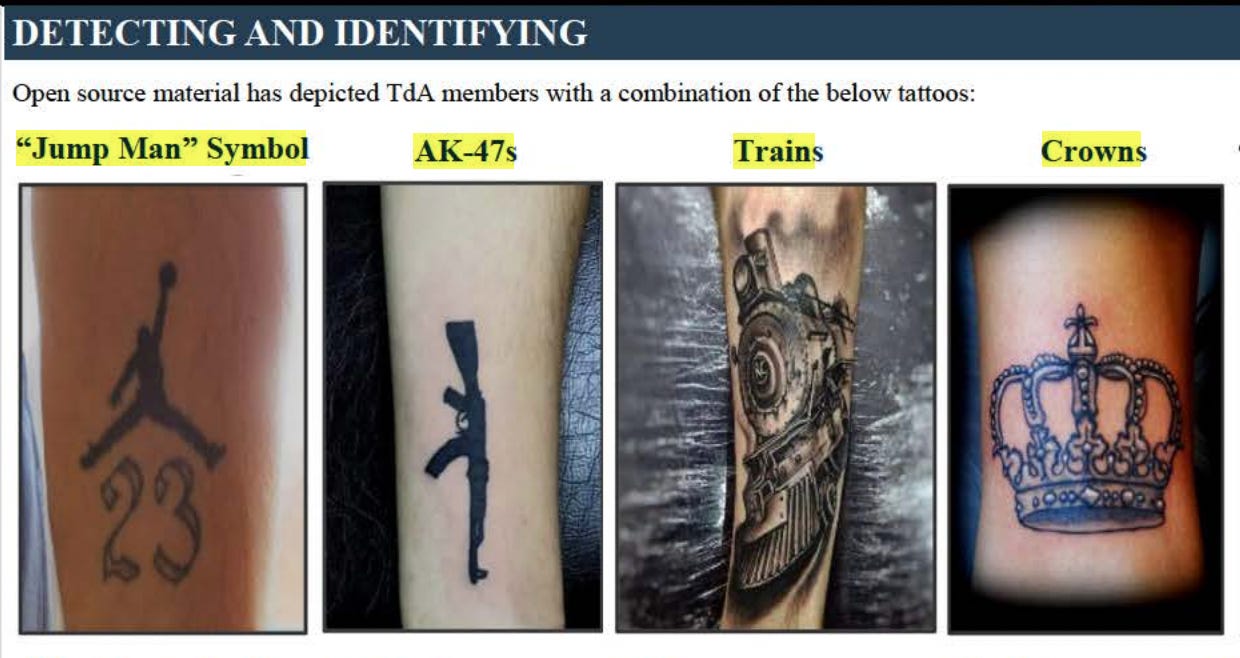

A separate Department of Homeland Security (DHS) document, also filed in federal court, on “detecting and identifying” TDA members, lists the tattoos it claims are associated with TDA. Among them is Jordan’s “Jumpman” logo, over his number for the Chicago Bulls, 23.

Of course, many people with Jordan tattoos are not gang members but simply fans of one of the greatest basketball players in history. Notably, the image in the DHS document is not of a gang member but a Jordan fan.

Other tattoos that the DHS claims are associated with TDA gang membership, including crowns, trains, stars, and clocks, are all symbols popular with the general public.

Nevertheless, a crown, star, or Jordan tattoo, according to the court documents, is worth four points. Someone can earn another four points for “dress known to indicate allegiance to TDA.” What “dress” indicates TDA allegiance? According to the DHS document, it includes “high-end street wear,” “Michael Jordan jerseys,” and Jordan sneakers.

Under this criteria, LeBron James, who has a crown tattoo and, like many NBA players, dresses in high-end street wear before games, would be “validated” as a member of TDA. (James would be spared deportation to El Salvador because of his American citizenship.)

Other “symbols” that seem more specific fall apart under scrutiny. For example, the DHS document claims the tattoo “Real Hasta La Muerte,” which means “Till Death,” indicates allegiance to TDA. But “Real Hasta La Muerte” is the title of a popular album by Anuel, a Puerto Rican reggaeton artist.

That is why other federal government documents obtained by USA Today warn that tattoos are an unreliable way of determining gang allegiances. A 2023 document from U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s El Paso Sector Intelligence Unit notes that “Chicago Bulls attire, clocks, and rose tattoos are typically related to the Venezuelan culture and not a definite (indicator) of being a member or associate of [TDA].” No tattoo establishes membership in TDA because TDA “doesn’t require its members to get tattoos.”

Even if the Trump Administration had a system to accurately identify TDA gang members, it lacks the legal authority to deport them without due process. The Trump Administration claims it has authority under a 1798 law, the Alien Enemies Act. That law, however, is “a wartime authority that allows the president to detain or deport the natives and citizens of an enemy nation.” It can be invoked only in the context of a “declared war” or “invasion” by “any foreign nation or government.” The United States is not at war with Venezuela and the 200 people, whether or not they are gang members, did not “invade” the United States on behalf of Venezuela.

As a result, a federal court has imposed a temporary restraining order (TRO) enjoining the Trump administration from continuing summary deportations. The Trump administration has appealed the decision to the Supreme Court.

Many Venezuelans were deemed gang members because of their tattoos

Several of the people who were detained and sent to El Salvador without due process do not appear to be gang members at all. According to family members and lawyers of numerous detainees, many do not have a criminal record or any affiliation with TDA, but were sent to El Salvador because of their tattoos.

Among the detainees is former professional soccer player Jerce Reyes Barrios. In 2024, Reyes Barrios participated in “antigovernment demonstrations in Venezuela.” According to a statement by Reyes Barrios’ lawyer, he was detained during a demonstration and tortured with electric shocks and suffocation. After he was released, Reyes Barrios, who does not have a criminal record in Venezuela, fled to the U.S. and was detained at the border by immigration authorities in September. In December, he applied for asylum. According to his lawyer, Reyes Barrios was accused of being affiliated with TDA because of his tattoos, which include “a crown sitting atop a soccer ball,” which is similar to “the logo for his favorite soccer team Real Madrid.”

Another detainee is Neri Alvarado Borges. According to his family, Alvarado, who came to the U.S. in late 2023, has no connection to TDA, Mother Jones reported. Alvarado was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in February, and told his boss that an ICE agent said he had been picked up because of his tattoos, which include “an autism awareness ribbon with his brother’s name on it.” Alvarado told his family that he explained his tattoos to an ICE official, who decided he had “nothing to do with” TDA, but another official decided to keep Alvarado detained. He was later sent to El Salvador.

Andry Jose Hernandez Romero also appears to have been sent to El Salvador because of his tattoos, which include the words “mom” and “dad” with crowns above them. Hernandez, who works as a make-up artist, was detained in August 2024 at a port of entry because of his tattoos, according to an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filing posted on X by Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council. Hernandez maintained that he was not affiliated with TDA.

Another detainee was sent to El Salvador despite having legal refugee status, the Miami Herald reported. E.M., who the Herald did not name for safety purposes, was granted refugee status along with his girlfriend in January after they fled Venezuela in fear of government persecution. Upon arrival in the U.S., E.M. was asked about his tattoos, which include a crown and a soccer ball, and was detained on suspicion of being associated with TDA, despite having no criminal record in Venezuela and already having undergone an extensive background check.

One detainee, Frengel Reyes Mota, was sent to El Salvador despite having no criminal record in Venezuela, no tattoos, and no affiliation with TDA, according to his family, the Miami Herald reported. Reyes Mota, who came to the U.S. with his wife and child in 2023, has an ongoing asylum case. In February, he went to an ICE office for a “required check-in,” where he was placed in custody for suspicion of being affiliated with TDA, his family told the Herald. According to the Herald, a DHS document that claims Reyes Mota may be associated with TDA acknowledges that he does not have a criminal record, and incorrectly uses “someone else’s last name in several parts of the document.”

“We’re better than this”

Some of these men, who were deported to El Salvador with no due process, may have been used to create propaganda promoting the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown.

Last week, Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem posted a video from the prison in El Salvador where the United States is sending deportees. Noem was touring the facility and meeting with El Salvador’s president to discuss increasing deportation flights to the country. Dozens of shirtless, tattooed inmates stood silently facing the camera in a cell behind Noem as she warned anyone coming into the U.S. illegally that “this is one of the consequences you could face.”

Critics have accused Noem of using her tour of the notorious prison as an opportunity to create propaganda, exploiting its inmates as props. The executive director of the Latin American Working Group, a human rights organization, told The Guardian that the prison visit “was a typical gross and cruel display of political theater that we have come to expect from the Trump administration.”

A former spokesperson for DHS under the Biden administration responded to Noem’s video on X: “No American—Republican or Democrat—should accept DHS using [a Salvadoran prison] to sidestep the Constitution. Stripping due process is un-American, full stop. We don’t protect our country by abandoning the principles that define it. We’re better than this.”

In times of war, distributing images and videos of prisoners of war as propaganda — like the video Noem posted — would be a violation of the Third Geneva Convention.