What Happened to Nazi Germany’s Giant U-Boat Pens Built to Survive 1,000 Bombs After WW2?

May 8th, 1945. The port city of Lauron, France, falls silent for the first time in five years. The last German garrison commander signs the surrender documents with trembling hands. Outside, Allied soldiers march cautiously through the rubble strewn streets, their boots crunching on broken glass and spent shell casings.

But towering above the devastation stand structures that seem untouched by the apocalypse that just consumed Europe. Massive concrete fortresses, each the size of a city block, their roofs 16 ft thick, designed to withstand direct hits from the heaviest bombs the Allies could drop.

These are the Yubot pens, the underwater cathedrals that sheltered Hitler’s most feared weapon, the submarine fleet that nearly strangled Britain into submission. The war is over. Nazi Germany is defeated. But these monuments to industrial warfare remain, scattered along the Atlantic coast from Norway to France. Some tower eight stories high.

Others stretch for over a,000 ft in length. Together they represent over 8 million cub meters of reinforced concrete, more than was used to build the Hoover Dam. The Allies dropped thousands of bombs trying to destroy them during the war. They failed. Now with peace declared, a new question emerges. The war was over. But a new mystery was just beginning.

What really happened to these indestructible fortresses after the guns fell silent? Between 1940 and 1944, Nazi Germany constructed these massive yubot bunkers across occupied Europe with fanatical determination. The largest complexes were built in France at Breast, Lauron, San Nazair, Lar Rochelle and Bordeaux.

In Norway, they carved pens into the sides of fjords at Bergen and Tronheim. In Germany itself, massive facilities rose in Hamburg, Braymond, and Keel. Each bunker could shelter between eight and 30 submarines simultaneously, protecting them from Allied air raids, while crews rested and engineers performed repairs.

The Nazis poured the concrete day and night, using over half a million slave laborers and prisoners of war. Many died in the construction, buried in the foundations, or crushed by falling debris. By 1944, these pens could service the entire operational Yuboat fleet, nearly 400 submarines in complete safety from aerial attack.

The British tried everything to destroy them. In 1943, the Royal Air Force developed the Tallboy bomb, a 12,000lb earthquake bomb designed specifically to crack these concrete monsters. Imagine the scene. Waves of Lancaster bombers appearing over the French coast. Their bomb bays carrying these massive weapons. The tall boys fell like meteors punching through the air at near supersonic speeds.

They struck the bunker roofs with the force of localized earthquakes. The ground shook for miles. Concrete dust erupted in vast clouds. But when the dust cleared, the bunkers remained. The roofs showed craters and scars, but the structure held. The submarines inside were safe. Later, the British developed the even larger Grand Slam, a 22,000lb monster.

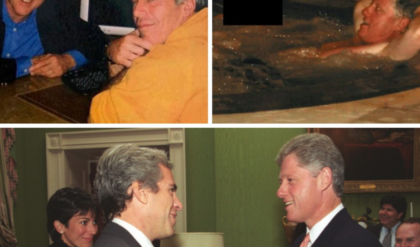

These bombs could penetrate 20 ft of concrete. But the bunker roofs were designed with multiple layers, sacrificial outer shells that would absorb the blast before the bomb reached the main structure. The Nazis had built them too well. Now it’s June 1945, one month after surrender. American engineers stand inside the yubot pen at breast, staring up at the vaulted concrete ceiling.

Their flashlights cut through the darkness, illuminating massive steel doors and the empty pens where submarines once floated. The water in the pens is black and still, reflecting nothing. The air smells of diesel fuel, seawater, and decay. These engineers have orders to assess the damage and determine what to do with these structures.

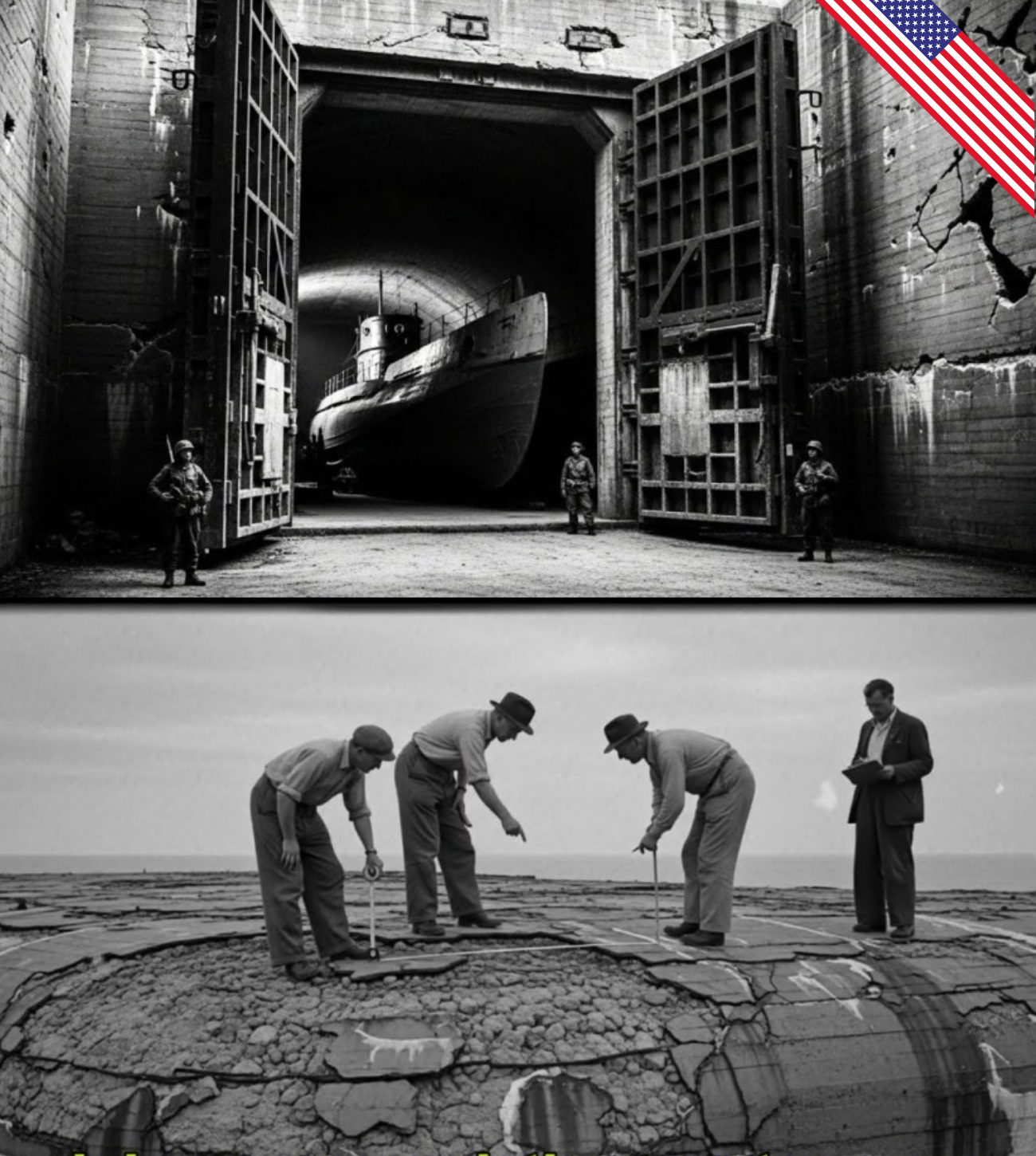

They walk through corridors designed to withstand direct bomb hits, past machinery rooms, with equipment stripped bare by retreating Germans, through barracks that once housed thousands of submariners. They take measurements. They photograph everything. They write reports. And in those reports, they reach a disturbing conclusion.

Conventional demolition won’t work. The bunkers are too massive, too reinforced. Destroying them would require more explosives than many military operations during the war itself. The French want them gone immediately. These bunkers represent 5 years of occupation, of forced labor, of watching their ports turned into Nazi fortresses.

In Laurant, the mayor pleads with Allied authorities to demolish the pens that dominate his city’s waterfront. The entire city center was destroyed by Allied bombing trying to hit these bunkers. Yet the bunkers survived while thousands of French homes were reduced to rubble. The bitter irony is inescapable. But the engineers shake their heads.

They show the mayor calculations, drawings, explosive requirements. To demolish the Kaman bunker complex in Laurian would require hundreds of tons of explosives planted in precisely calculated positions detonated in a carefully orchestrated sequence. The cost would be astronomical. The risk of uncontrolled collapse that could damage surrounding areas is too high and even then success is not guaranteed.

So the bunkers remain through 1945 and into 1946. Allied authorities debate their fate. The British Navy proposes using the pens at Sanair for their own submarines. The suggestion causes outrage in France. The French government firmly rejects any continued military use of structures built by slave labor during the occupation.

Meanwhile, nature begins to reclaim the abandoned fortresses. Seawater seeps into the lower levels. Rust blooms on the massive steel doors. Pigeons nest in the ventilation shafts. Graffiti appears on the walls. Crude messages from soldiers and curious locals who venture inside. By 1947, the scrap metal dealers arrive. If the bunkers themselves cannot be destroyed, at least their contents can be salvaged.

Teams of workers weighed into the flooded pens, cutting apart the machinery the Germans left behind. Imagine the scene. Workers with acetylene torches, the blue white flames reflecting off dark water, cutting through massive steel cranes that once lifted yubot engines. They dismantle the rail systems that transported torpedoes.

They tear out electrical panels, piping, ventilation systems. Anything metal has value in post-war Europe, where steel is desperately needed for reconstruction. The workers fill trucks with scrap, hauling away the mechanical guts of the bunkers, leaving only the concrete shell. But some bunkers serve new purposes.

In Bordeaux, the French Navy quietly begins using the submarine base for their own vessels. Despite earlier protestations about military reuse, practical necessity wins. The base is simply too valuable to abandon. By 1948, French submarines are tying up in the same pens where German yubot once sheltered. The irony is noted by few and mentioned by fewer.

In Hamburg, the British occupation authorities convert parts of the Frink 2 bunker into emergency housing. Imagine families living in compartments designed for storing torpedoes. Children playing in corridors where German submariners once walked. The concrete walls that protected submarines from bombs now protect civilians from the rain and cold.

By 1950, over 300 people are living inside this former Yubot pen. Their laundry hanging from lines strung across the massive interior spaces. The Norwegian pens present a different problem. The bunker at Bergen was partially carved into solid rock, a hybrid structure of natural granite and reinforced concrete. The Norwegian government looks at it and sees only one solution. Seal it.

In 1948, engineers use explosives to collapse the entrance tunnels. Thousands of tons of rock and concrete crash down, blocking access to the interior chambers. But they cannot destroy the bunker itself. It’s literally part of the mountain now. So they bury it, build over it, pretend it doesn’t exist. For decades, the bunker will lie hidden beneath parking lots and warehouses, a secret void in the heart of Bergen.

In 1949, something unexpected happens at the La Palace bunker in Lar Rochelle. French engineers inspecting the structure discover that the roof, despite withstanding countless bomb strikes during the war, has begun to deteriorate, not from bombs, but from the sea air. The concrete is slowly degrading, the rebar inside corroding and expanding, causing cracks to spread through the massive roof sections.

The problem is the concrete mixture itself. The Nazis, desperate for speed during construction, used seawater mixed with the concrete in violation of proper engineering practice. Now 5 years later, the salt is destroying the structure from within. Repairs begin. A bizarre situation where the French are now maintaining the very bunkers they wanted destroyed.

But allowing them to collapse naturally would be catastrophic. Each bunker sits on valuable waterfront land near residential areas. An uncontrolled collapse could kill dozens. The 1950s bring a new use for some bunkers. The Cold War. At breast, the French military converts sections of the Yubot pens into storage facilities for naval equipment and ammunition.

The same thick concrete that protected yubot from Allied bombs will now protect French military supplies from potential Soviet attack. Access is restricted. Guards patrol the entrances. For the next four decades, these sections of the bunkers become classified military zones. What exactly is stored inside remains unclear. Rumors circulate among breast residents, nuclear weapons, chemical agents, submarines for France’s new nuclear deterrent force.

The truth remains locked behind those massive concrete walls. But other bunkers are simply abandoned. The pen at Keel, partially destroyed during the final days of the war, becomes a dumping ground for rubble. For years, trucks arrive daily, pouring construction waste and debris into the ruined sections. By 1955, parts of the complex are buried under mountains of broken concrete and twisted rebar from other demolished buildings.

The city is literally using one ruin to bury others. In Sanair, the Allies experimented with a radical solution. In 1946, British engineers brought in experimental munitions, attempting to crack the bunker’s roof with newly developed shaped charges. They detonated over 50 tons of explosives in a series of carefully planned blasts.

The explosions shook the entire city. Windows shattered half a mile away. When the smoke cleared, the engineers surveyed the damage. They had succeeded in creating several large craters in the outer roof, but the main structure held. The bunker had survived again. Decade by decade, the bunkers persist.

The 1960s see new interest in these structures. As France’s economy booms, developers eye the prime waterfront real estate occupied by the massive concrete blocks. Proposals emerge. convert them into shopping centers, office buildings, parking garages. But every proposal confronts the same problem. The bunkers are too large, too solid, too expensive to modify.

Converting them would cost more than building new structures from scratch, so they sit massive gray monuments to a war that grows more distant with each passing year. Then in 1968, something remarkable happens at the Keraman bunker in Lauron. The city desperate for industrial space decides to convert part of the complex into a shipyard facility.

Workers install new equipment, modern cranes, welding stations. The same pens that once sheltered yubot now service fishing trollers and merchant vessels. The thick concrete walls that withstood Allied bombs now serve as perfect windbreaks for delicate repair work. The conversion is successful. Other cities take notice. Perhaps these indestructible fortresses could serve peaceful purposes after all.

The 1970s bring an unexpected development. Tourism. As the war generation ages and memories shift from rage to curiosity, people begin to see these bunkers differently. In 1972, a group of historians in San Nazair convinces the city to open part of the submarine base for guided tours. They clean out one section, install lighting, createformational displays.

The first tours are small, tentative, but word spreads. By 1975, thousands of visitors annually walk through the echoing chambers, staring up at the massive roof, imagining the submarines that once floated here. The tours are somber, educational, controversial. Some locals protest, arguing the bunkers should not be glorified.

Others see an opportunity to teach younger generations about the war, about the cost of fascism, about the suffering of the forced laborers who built these structures. But many bunkers remain hidden, forgotten. In Hamburg, entire sections of the Yubot pens lie sealed and unexplored. Their entrances bricked over in the late 1940s and never reopened.

What’s inside them? Old machinery, abandoned submarines, human remains. Nobody knows. The records from the final days of the war are incomplete. In the chaos of surrender, much was lost or destroyed. These sealed chambers hold secrets that may never be revealed. The 1980s bring an environmental crisis. Inspectors discover that several bunkers are leaking diesel fuel and other chemicals into the surrounding water.

Decades of use as naval facilities have left the pens contaminated. The thick concrete walls that made the bunkers indestructible also make them nearly impossible to clean. Standard decontamination procedures don’t work. The pens are too large, the water too deep, the residue too pervasive. Cleanup efforts begin at several sites costing millions of franks.

Workers in protective suits weighed through contaminated water, pumping out toxic sludge accumulated over 40 years. In 1986, a German historian makes a disturbing discovery in the archives. Construction records for the bunkers include lists of the forced laborers who built them, thousands of names, French resistance members, Soviet prisoners of war, Jews from across occupied Europe, political prisoners from a dozen countries.

The historian begins compiling a complete record, tracking down survivors, collecting testimonies. The stories are horrific. Workers forced to labor 20-hour shifts pouring concrete. men who collapsed from exhaustion and were left where they fell, buried in the very structures they were building. The bunkers are not just military installations.

They are mass graves. This discovery changes everything. By the 1990s, memorial plaques begin appearing at bunker sites. Small ceremonies are held, attended by the dwindling number of survivors and their families. The bunkers become officially recognized as sites of Nazi crimes, places where slave labor built monuments to tyranny.

In Laurent, a permanent exhibition opens inside the Keraman complex, documenting both the military history and the human cost of construction. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 brings new revelations. East German records long sealed reveal that several Ubot were never destroyed after the war. In 1946, the Soviets secretly transported three captured yubot to Lenengrad, studying German submarine technology to improve their own fleet.

These submarines were eventually scrapped in the 1960s, but for decades they remained operational, training Soviet naval officers in facilities that eerily mirrored the German pens they once called home. The year 1991 sees an ambitious proposal at the Sat Nazair bunker. A French businessman suggests converting the entire complex into an interactive museum and cultural center.

The plan is massive. remove contamination, install modern systems, create exhibition spaces inside the pens themselves, build a roof garden at top the 16 ft thick concrete roof. The project takes 8 years and costs over 20 million. But in 1999, the Escal Atlantic Museum opens, transforming the bunker into one of France’s most visited historical attractions.

Visitors walk through recreated ship interiors, learn about transatlantic travel, and confront the dark history of the structure itself. The transformation is complete. A weapon of war becomes a tool for education. But not all bunkers receive such care. The pen at Keel, partially buried under rubble in the 1950s, is completely demolished in 1997.

Engineers spend three years methodically cutting the structure into manageable pieces using modern explosives and cutting techniques unavailable in 1945. The demolition costs over 15 million Deutsche marks proving that the postwar engineers were right. Destroying these bunkers is phenomenally expensive.

The Keel demolition is one of the largest controlled demolition projects in European history. When it’s finally complete, over 300,000 tons of concrete have been removed, crushed, and hauled away. As the new millennium arrives, a strange renaissance occurs. The bunker at Bordeaux, used by the French Navy for decades, is decommissioned in 2010.

The military moves out. The city debates demolition. But a group of artists and cultural organizers proposes something radical. turn it into a digital art center. The proposal seems absurd, these cold, dark spaces filled with art installations. But in 2013, the Basand Lumiere opens, projecting massive digital artworks onto the interior walls of the submarine pens.

Images of Van Go’s paintings, 40 ft tall, swirl across concrete that once echoed with the sounds of torpedo loading. The contrast is jarring, profound, strangely moving. Hundreds of thousands visit annually. Today, in 2024, the bunkers remain scattered across Europe, each with its own fate. The Keraman complex in Lauron still serves as an industrial shipyard.

Its original purpose barely modified. The San Nazair bunker hosts museums and cultural events. The lalis structure sits partially abandoned, partially used for storage. Its massive bulk dominating the Lar Rochelle waterfront. In Norway, the Bergen bunker remains sealed beneath the city, its chambers dark and empty, accessible only through restricted tunnels known to a handful of maintenance workers.

The Bremen bunker, one of the largest, presents an ongoing dilemma. Too expensive to demolish, too contaminated to safely repurpose. It sits behind fences slowly degrading. Urban explorers sometimes break in, posting videos of the eerie interior spaces online. The videos show flooded chambers, collapsed sections, graffiti covering walls where German naval charts once hung.

Nature is slowly reclaiming this bunker as water seeps through cracks in the concrete and vegetation takes root in accumulated debris. Recent technological advances have allowed historians to explore previously inaccessible sections. In 2019, a team using ground penetrating radar discovered sealed chambers in the Hamburg bunker spaces that were walled off during the final days of the war and never reopened.

The radar images showed large voids containing metallic objects. Are they abandoned machinery, weapons, submarines that were sealed inside rather than surrendered? Funding is being sought to carefully excavate these spaces, though the technical challenges are immense. The environmental legacy of these bunkers continues to emerge.

In 2021, inspection teams at several French bunkers discovered that groundwater flowing through cracks in the foundations has carried contamination far beyond the structures themselves. Diesel fuel, heavy metals, and other toxic substances have spread through the underlying soil and into nearby waterways.

Cleanup efforts are ongoing, but the scale of contamination suggests remediation could take decades and cost hundreds of millions of euros. Some bunkers face unexpected threats. Rising sea levels caused by climate change are affecting the Lar Rochelle bunker built close to sea level. During high tides and storms, seawater now floods lower sections that remained dry for 70 years.

Engineers are studying whether climate change will eventually make some coastal bunkers unstable or uninhabitable. Though the irony of structures designed to withstand bombs being threatened by rising water is lost on no one. The last living forced laborers who built these bunkers are now in their 90s and hundreds.

Their testimonies recorded by historians over the past decades provide the only direct link to the construction years. They describe the brutal conditions, the inadequate food, the arbitrary punishments, the deaths that occurred almost daily. They speak of mixing concrete with bare hands that cracked and bled, of working through winter with insufficient clothing, of watching fellow prisoners collapse and die.

Their stories ensure that these structures will never be seen as mere engineering achievements, but as monuments to suffering. Modern Germany has confronted this legacy directly. In 2018, the German government officially recognized the Yubot bunkers as sites of war crimes and allocated funding for memorial projects at each location. Educational programs now bring school groups to the bunkers, teaching them about forced labor, resistance, and the human cost of Nazi military ambition.

The programs are mandatory for many German students, ensuring that new generations understand what these concrete monsters represent. The bunkers have also become unexpected assets for climate research. The massive concrete structures, largely unchanged since the 1940s, provide baseline data for studying concrete degradation in marine environments.

Scientists examining the bunkers have learned valuable lessons about long-term concrete durability. Information now being used to design modern coastal infrastructure. The Nazis built these structures to last a thousand years. They’re providing data that will help engineers build better for the next hundred. Today, if you stand on the waterfront at Laurant and look at the Keraman bunker complex, you see a massive gray fortress stretching nearly half a mile along the coast.

Its walls are scarred by unsuccessful bomb strikes. Its roof, visible from certain angles, shows the craters where tall boys and grand slams impacted. Rust streaks run down the concrete from corroding rebar, but the structure stands as solid as the day it was completed. Ships still use the pens. Workers still enter through the massive steel doors.

The bunker has outlived the regime that built it, outlived most of the men who constructed it, outlived the purpose for which it was designed. These indestructible fortresses were meant to ensure Nazi victory. Instead, they became monuments to Nazi defeat, to the futility of war, to the persistence of memory. They cannot be erased.

They cannot be forgotten. They remain scattered across Europe, too massive to destroy, too significant to ignore. They stand as permanent reminders that some things once built, cannot be undone. That history, like reinforced concrete, is stubborn and enduring. That the past, no matter how much we might wish it buried, will not easily crumble and fade