Engineers Called a 1,000-Pound Cannon “Pilot Suicide” — Until It Stopped a 2,000-Ton Warship

The Flying Cannon: How a “Suicide Box” Changed the Pacific War Forever

At 9:17 a.m. on a humid morning in early 1942, a twin-engine bomber skimmed just 50 feet above the Pacific, salt spray slapping its aluminum skin. Inside the cockpit, silence reigned—not for lack of words, but because everything that mattered had already been decided. Ahead, a Japanese destroyer sped through the water at over 30 knots, its guns and anti-aircraft barrels trained skyward. From the ship’s bridge, the American bomber looked like a mistake: too low, too slow, too close. And yet, it kept coming.

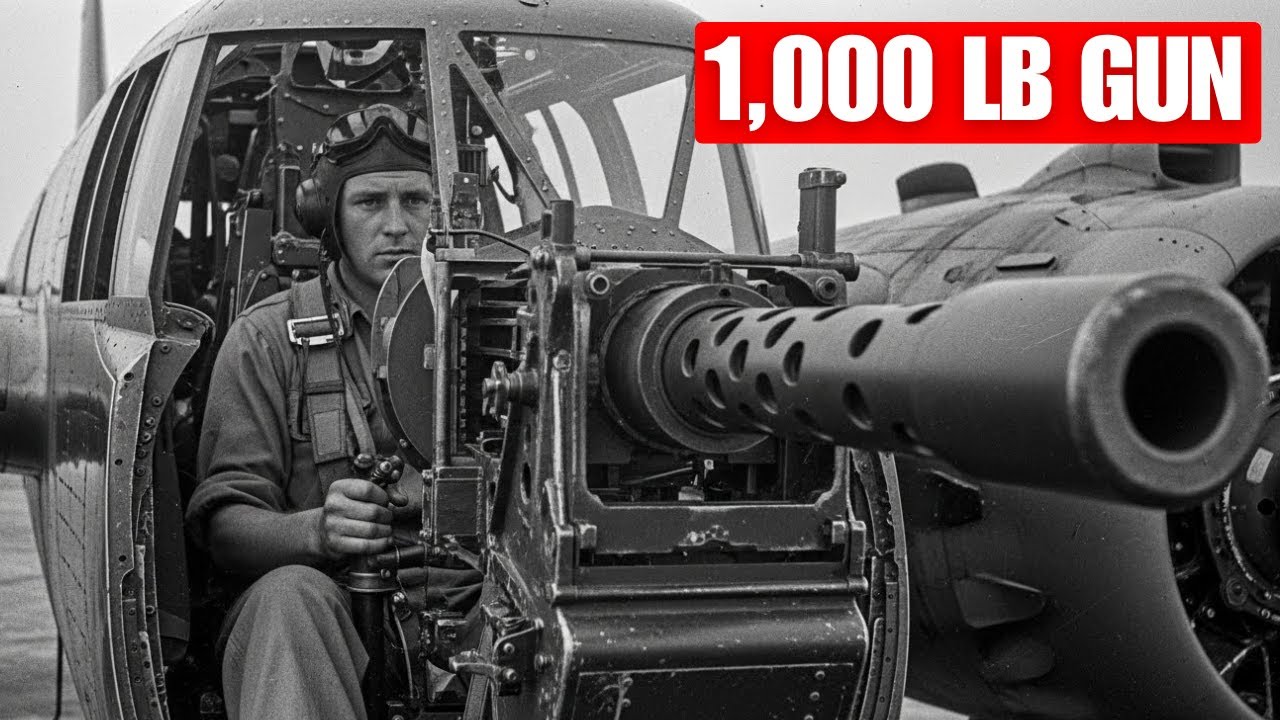

Bolted inside the nose of that bomber was something that shouldn’t have existed—a 75mm field cannon, the same weapon used to smash bunkers and tanks, weighing nearly 1,000 pounds. Every engineer who saw the plans called it “pilot suicide.” The math seemed irrefutable: the recoil alone could tear off the nose, stall the aircraft, black out the pilot, or fold the wings. The danger wasn’t the enemy—it was the trigger.

Yet, on that morning, the bomber did not climb, did not turn away, did not open bomb bay doors as doctrine demanded. Instead, it dropped lower, aiming straight at the destroyer’s bow. Closing speed: 400 mph. Japanese gunners opened fire, tracers ripping upward, flak bursting around the plane. One direct hit would have erased the bomber instantly. Still, it held its line.

Inside, the pilot had no bombsight, no computer, no radar—just a fixed ring sight and nerve. To aim the gun, he had to aim the plane itself. At roughly 800 yards, the machine guns fired first, blinding the ship’s bridge and gunners. For a brief moment, the wall of fire weakened. The destroyer filled the windshield. The pilot made a micro adjustment, lifting the nose to aim at the waterline beneath the forward turret—where the boilers lived, where one hit could change everything. The shell was loaded. The pilot squeezed the trigger.

For an instant, the bomber seemed to stop in midair. The recoil slammed through the fuselage, smoke filled the cockpit, the airframe shuddered. This was the moment engineers had predicted disaster. But the wings held. The shell crossed the water in less than a second, struck above the waterline, punched through steel, detonated inside the ship. Power failed, steam erupted, and the destroyer began to lose speed. The bomber roared overhead, engines shaking, wings still attached. The impossible had just happened.

When Doctrine Fails

At 20,000 feet above the Solomon Sea, the theory looked perfect: tight formations, calm air, bomb bay doors opening on schedule. Below, Japanese convoys sliced through the water. Precision bombing was supposed to be the future. But the bombs fell for 45 seconds—plenty of time for a destroyer to travel half a mile. The bombs hit the ocean, not the ships. The Japanese captains simply turned the wheel, and survived.

The Nordon bombsight, a technological marvel, worked against stationary targets. Against a moving warship, it was almost useless. Pilots weren’t failing—the system was. Bombing runs followed the manual, but misses were measured in football fields. American air power could not stop the “Tokyo Express”—Japanese destroyers delivering troops and supplies to island garrisons night after night. Morale collapsed along with the math.

General George Kenney arrived in the Southwest Pacific and brought skepticism, not new manuals. He saw the reports and threw them away. Hitting a moving destroyer from 20,000 feet, he said, was like dropping a marble from a skyscraper into a coffee cup dragged by a sprinting cat. The longer the bomb fell, the more time the enemy had to maneuver and survive. Kenney asked not how to improve accuracy, but how to remove time from the equation. The answer: get closer. Closer meant lower. Lower meant danger.

The Birth of the Gunship

Low altitude put bombers inside every ship’s anti-aircraft envelope. It traded safety for nerve, but collapsed the timeline. At 50 feet above the water, there was no 45-second delay—there was impact almost immediately. The manual said this was suicidal. The numbers said losses would be catastrophic. But the alternative was losing the campaign, island by island.

Kenney didn’t know what the weapon would be, only what it couldn’t be—another high-altitude bomb. It had to hit now, hard, and deny the enemy time to think. Someone on a Pacific airfield asked: what if the airplane didn’t drop anything at all? What if it fired artillery?

The Army’s 75mm M4 field cannon fit the bill. Designed for concrete and armor, it weighed nearly 1,000 pounds, never meant to fly. Engineers said “no.” The recoil impulse would decelerate the plane violently, collapse lift, break the nose. The B-25 Mitchell was sturdy, but not built for this. Reports warned of “pilot suicide.”

But out in the Pacific, the problem was not theoretical. Japanese destroyers were unloading troops in daylight. American air power was helpless. Kenney understood: a perfect aircraft that cannot solve the problem is useless. He didn’t argue the equations. He accepted them, then accepted the consequences.

Building the Monster

Modifications began in sweat-soaked hangars. The B-25’s glass nose was cut off, replaced with blunt steel to hold the cannon. Mechanics bolted lead into the tail to balance the weight. The navigator’s station disappeared. The bombardier’s role vanished. In his place stood the cannoneer, whose job was to load 15-pound shells at combat speed. Test pilots said it handled like a “dump truck with wings.”

The first ground tests were tense. The recoil system was the only thing standing between the pilot and disaster. On the first live-fire test, the plane shuddered violently, smoke filled the nose, but the wings held. The shell hit exactly where aimed. The math had been wrong—not because the engineers were careless, but because reality is messier than equations. The idea was no longer insane. It was proven.

The New Way of War

The B-25 was now a weapon demanding a new kind of flying. The 75mm cannon was fixed. To aim, the pilot had to point 20 tons of airplane directly at the target, hold steady through turbulence and fear, and trust his hands. At low altitude, a mistake measured in fractions of a second was fatal.

Crews practiced diving at shipwrecks, learning how the sight picture changed with speed. Effective range on paper was thousands of yards. In combat, pilots learned they had to close to under 1,000 yards—sometimes close enough to see sailors on deck. This was not bravery as a personality trait. This was trained nerve, built through repetition and fear management.

The attack profile: descend to wave height, use terrain or cloud cover to mask approach, accelerate, line up, suppress deck guns with machine gun fire, fire the cannon, recover from recoil. If you survived, do it again. The rate of fire was slow—three rounds per pass if the cannoneer was strong and lucky.

Inside the cockpit, communication was rhythmic: load, ready, fire, clear, load, ready, fire. No room for hesitation. Any delay meant more exposure.

Japanese gunners adapted quickly. When they saw a bomber coming in low, they assumed torpedoes and turned the ship head-on, presenting the narrowest target. That instinct became a trap. By turning, destroyers aligned their most vulnerable spaces—boilers, engines, magazines—directly into the cannon’s path.

The Real Test

The first targets were barges—wooden hulls, minimal armament. Against bombs, they often survived. Against the cannon, one shell erased them. The psychological effect was immediate. Pilots returned shaken by the destruction. Word spread. The “suicide box” was now called the “hammer,” the “can opener,” the “lil monster.” Crews volunteered because it worked.

More guns were added—heavy .50 calibers clustered around the cannon. The “Commerce Destroyer” was born. Every barge destroyed meant fewer troops, less ammo, less food. In jungle warfare, logistics are everything.

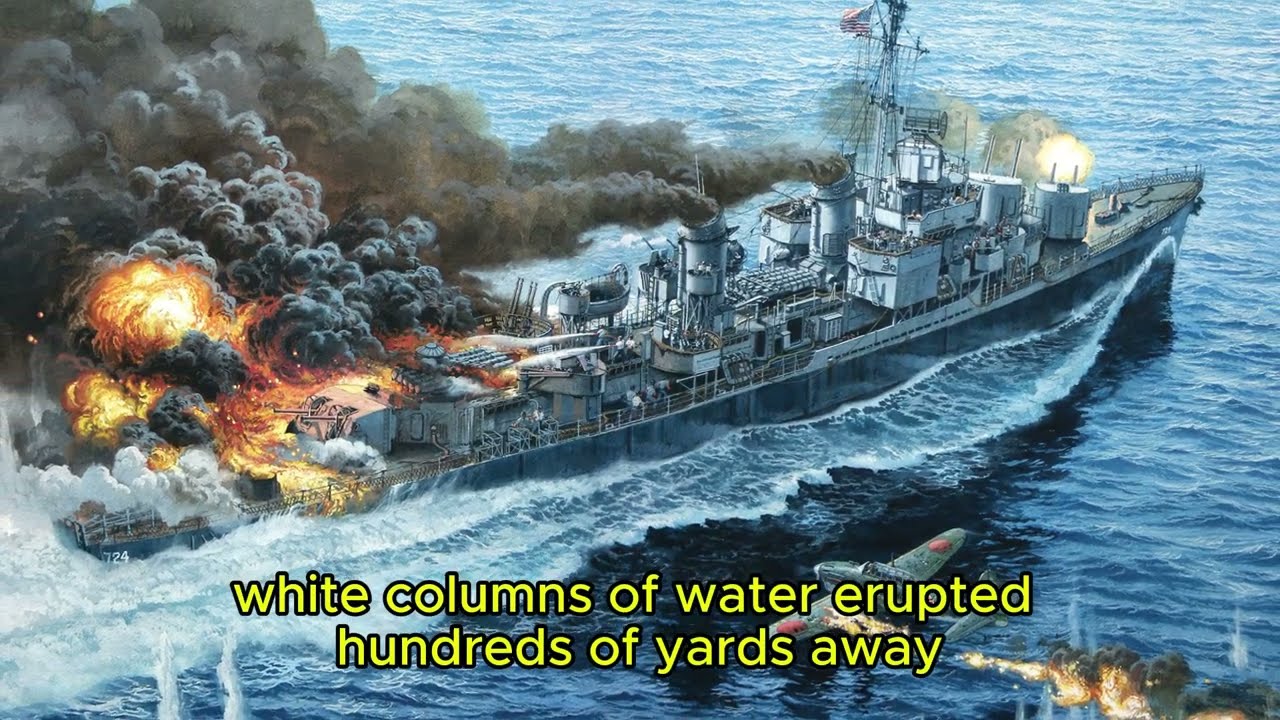

But the true test was destroyers. Late 1942, over the Bismarck Sea, a Japanese convoy moved south—transports guarded by fleet destroyers. The bombers descended through cloud gaps, leveled out at 50 feet. Japanese gunners opened fire. The lead destroyer turned head-on, sealing its fate. At 600 yards, the cannoneer loaded the shell, slapped the pilot’s shoulder. The destroyer filled the windshield. The pilot aimed at the waterline, fired.

The plane shuddered. The shell punched through steel, detonated inside the machinery spaces. Power failed. The destroyer was dead in the water. The second pass struck the stern, triggering secondary explosions. Within minutes, the convoy was chaos—burning transports, crippled escorts, oil slicks stretching for miles.

The Strategic Shift

This was not elegance. It was brutality applied with precision. The destroyer was not sunk by a battleship or submarine, but by an airplane firing a weapon that should never have flown. As the bombers turned for home, radios crackled with disbelief, laughter, relief. Behind them, smoke marked the water where doctrine had failed.

The surface ship was no longer king. Speed no longer guaranteed safety. Steel could be reached from the air in ways no one had prepared for. Japanese commanders changed behavior—daylight movement disappeared, convoys waited for darkness, routes bent closer to coastlines, speeds slowed. Every adjustment carried a cost. Supplies began arriving late, incomplete, or not at all.

The cannon did not just sink ships. It forced decisions. And decisions create friction. Japanese destroyers were now reacting instead of acting. The initiative had shifted.

Allied air planners noticed the change. Recon flights saw fewer ships by day. Radio intercepts hinted at rescheduled runs. The ocean was shrinking. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea made the shift undeniable. Aircraft attacked at wave height. Gunships suppressed defenses. Skip bombing followed. Transports were torn open. Destroyers crippled. In one engagement, an entire reinforcement effort was annihilated.

Legacy and Lessons

The impact was not just tactical, but strategic. The cannon forced logistical strangulation. An island army without food does not fight. An airfield without fuel does not fly. A garrison without ammo does not hold. Every ship that failed to arrive weakened the entire defense network.

Air power was no longer just about attrition from above. It became a tool of denial. Deny movement, deny resupply, deny choice. Once commanders expect losses, they act differently—more cautiously, more slowly. And war favors the side applying pressure.

The cannon was not perfect—heavy, demanding, dangerous. Losses still occurred. But effectiveness does not require perfection. It requires leverage, and leverage is what this weapon provided.

By late 1942 and into 1943, B-25 gunship variants entered full service. Tactics evolved—suppression, skip bombing, coordinated runs. The Pacific War became less about single battles and more about sustained pressure. Supply lines frayed. Islands became liabilities.

By 1944, the 75mm cannon was already becoming obsolete. Rockets arrived—lighter, faster, easier to aim. The big gun faded into surplus yards. But if the cannon had truly been a mistake, it would have disappeared. Instead, its legacy lived on. Two decades later, the AC-47 and AC-130 gunships circled targets, raining fire from the sky. The concept was the same—only the technology caught up.

The Moral Tension

Were the engineers wrong? Their calculations were sound. They protected crews from catastrophe. But war does not reward caution equally. General Kenny was not ignoring science—he was weighing different deaths: the loss of aircraft versus the slow death of a campaign.

Innovation does not come from comfort. It comes from failure. And failure compresses decisions until risk becomes acceptable. The cannon’s career was short, but its impact was not. It broke the illusion that surface ships were safe from low-level air attack. It forced behavioral change. It bought time. It strangled supply lines. It altered expectations. And expectations decide wars long before treaties do.

So here is the question: If you were an engineer in 1942, looking at those stress charts, would you have approved this aircraft? The story of the flying cannon is not about perfect ideas. It’s about people willing to act when perfection fails. And that truth is still uncomfortable.