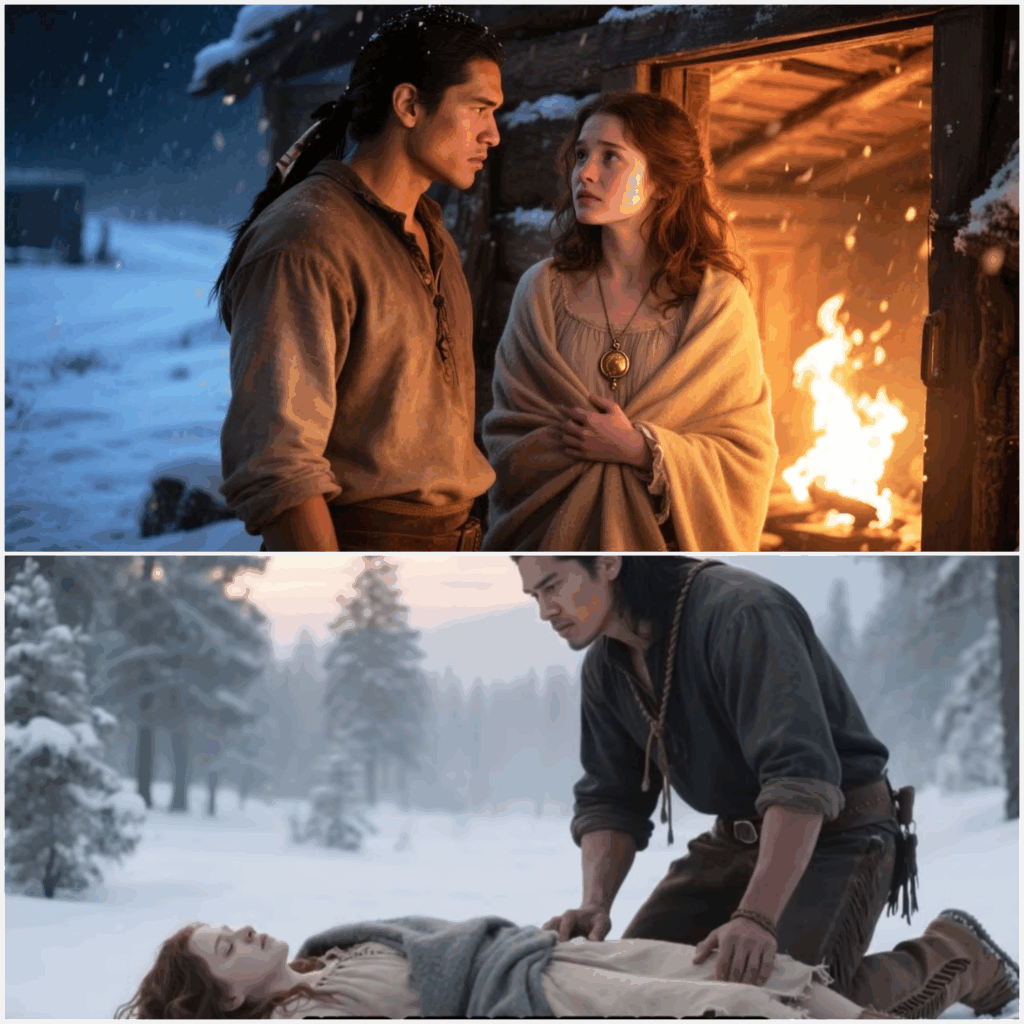

I Can’t Control Myself Around You — The Apache Warrior Took the Lost Woman to His Fire

.

.

I Can’t Control Myself Around You — The Apache Warrior Took the Lost Woman to His Fire

The wind came sharp off the ridgeline, laced with the bitter bite of pine smoke and snow. It whistled through the seams of the canvas bunkhouse, cold as regret. Lucy Monroe stepped out into the still-dark morning, her boots crunching hard frost as she pulled her shawl tighter across her shoulders. The sky was the color of old bruises—deep violet with a rim of sickly gold at the edges, promising another sunless day.

The Hollow Ridge mining camp sat like a blister on the mountains’ edge—a scatter of tents, two ramshackle cabins, and a weather-warped church. Twenty-seven men, four women, and not a soul among them with clean hands. Lucy had counted them. She always counted. She was eighteen and already carried the weary manner of someone older. Life had taught her to walk softly, speak rarely, and never meet a man’s eyes longer than needed. The only thing that had kept her safe this long was being useful and invisible. She cooked, hauled water, swept out the chapel tent before Reverend Briggs droned his sermons about fire and sin.

Her mother had died of fever when Lucy was ten, back in Kansas. The man who took her in, George Harland, called himself her stepfather but acted more like a creditor. He was a mule skinner by trade, a drunk by habit, and a coward by nature. He’d dragged her west, chasing fortune through gold dust and broken promises.

That morning, Lucy spotted George speaking with Merrick Sloan, the mine foreman. Tall and thick-shouldered, Sloan carried himself like a man who believed the land owed him something. His black coat flapped in the wind as he leaned in close to George, voice low, smile crooked like a snake’s tail. Lucy ducked behind the cook tent and watched them from the corner of her eye. The way they stood, the way George wouldn’t quite meet his gaze, made something go cold in her stomach.

Later, George found her hauling firewood. “Put on your blue dress,” he said without looking her way, his voice rough but not loud. That was always worse. “Wash your face. Tie your hair back proper. We’ve got company tonight.” She stood frozen. “Who?” His eyes flicked toward her, flat and gray. “Don’t ask me that again.”

That evening, the sky hung low with snow. Inside the supply tent, lit by two oil lamps and heavy with smoke, Merrick Sloan sipped from a glass of brandy and watched Lucy like she was a prize calf up for auction. “You’re a quiet little thing,” he said. “That’s good. A man needs quiet when he comes home.” George said nothing. He hadn’t touched the drink Sloan poured him. He only nodded, hands clasped between his knees. “I can give her a roof,” Sloan continued. “Food, protection—and I hear you’ve got some timber rights need settling.” George grunted. That was as close as he’d come to a blessing.

Lucy didn’t speak. Her throat had closed up tight. The blue dress itched at her neck. Her mother had stitched the hem years ago, back when things were gentler, back when there was still music in the house.

Later that night, in the bunkhouse with the other women already asleep, Lucy packed what she could fit in a small cloth bundle: her mother’s locket, a wool shawl with one torn corner, a small tin cup, a pocketknife barely sharp enough to slice bread. The camp was quiet as she slipped through the shadows. She kept low, stuck to the trees beyond the tents, boots crunching softly over ice-crusted snow. The cold bit through the dress within minutes. Her breath came quick and white, and she didn’t dare look back. She didn’t know where she was going, only that she was going. She followed an old game trail east, climbing higher along the ridge, past the treeline where the woods grew thick with black spruce and silence.

Owls called once. A fox watched her from beneath a ledge, and vanished. The cold grew worse. Her shawl turned stiff. Her hands stung. Still, she pressed on. She came to a boulder with a hollow at its base, half-sheltered from the wind, and crawled inside. Her body shook with cold. Her teeth clacked so hard it hurt. She pulled her knees to her chest, wrapped herself tight, and clutched the locket close. She didn’t pray, not exactly, but she whispered her mother’s name once like a promise. Then sleep came—a kind of sleep that felt like falling through snow. Slow, endless, silent.

Far above her on the ridge, someone watched. He didn’t move right away, just stood there, boots sunk deep in snow, dark eyes scanning the trail she’d left behind. His hair was tied back with a strip of leather. A bow rested across his shoulder. Reed Greyhawk had seen a thousand footprints in the snow. None like hers, none with that kind of desperation. And when he saw the locket she clutched in frozen fingers, the small brass circle worn smooth by years, he knew. That red thread tied to it was no accident. It was a sign, and it had found its way home.

Lucy stirred before her eyes opened. For a moment, she felt nothing. No cold, no pain, no sense of time or place, only the slow return of sensation, the weight of her limbs, the ache in her feet, and the sharp sting of air against cracked lips. Then came the smell of smoke and pine, and something bitter like dried sage burned too close to the fire. She blinked. The world swam into focus. A low ceiling of rough-cut logs, shadows moving gently across it. Her cheek pressed against fur, real fur, thick and musky. A fire crackled nearby. Someone moved just out of view, slow and steady.

She sat up too quickly, and the world tilted. A voice came, quiet but firm. “Don’t.” Lucy froze. Her heart thudded like hooves on hard ground. The man stepped into view. Tall, broad-shouldered, dressed in layered buckskin and wool, his hair black and tied back. His eyes, dark and unreadable, met hers with calm, but no welcome. “You need rest,” he said. Lucy opened her mouth, then closed it. Her throat was too dry for words. “Who… who are you?” she managed. He crouched near the fire, added another piece of wood. “Name’s Reed.” His voice had a rough edge like bark stripped from old wood.

He poured warm water into a tin cup and handed it to her. Lucy’s hands trembled as she took it. The warmth stung her palms. She drank slowly, carefully, until the cup was empty. Reed moved to the back of the small shelter, a hunting lodge built into the rock itself. One opening served as a door, covered with a heavy wool curtain. Two deer hides were stretched near the fire, and in the corner sat a bundle of gear—a bow, a quiver of arrows, a coil of rope.

She looked down. Her boots had been removed. Her feet were wrapped in cloth—clean, warm, and scented with something earthy. A blanket covered her legs. Whoever this man was, he’d cared enough to keep her alive. “Where am I?” she asked, her voice rough as gravel. “High Ridge, south face,” he said simply. “Storm came in last night. You would have died out there.” Lucy looked into the fire. She wanted to argue, wanted to say she could have made it, but her body knew the truth. Every bruise, every cut said so.

“Why’d you help me?” she asked quietly. Reed turned, crouched again, and held something in his hand. “Her locket. This was around your neck,” he said. She reached for it instinctively. He didn’t stop her. “You know what this is?” he asked. She looked at the locket. The red thread looped through its chain had faded to rust, but it was still tied in a specific knot. “My mother’s,” she said. “She wore it always.” “Your mother Apache?” Lucy blinked. “No… I don’t think so. She never said.” Reed’s gaze didn’t soften, but it changed—a flicker of something behind his eyes, memory perhaps, or recognition.

“My grandmother used to tie thread like this,” he murmured. “To remember those taken, or lost, when silence settled thick as snowfall.” The fire cracked once, sharp and sudden. Reed stood, moved to stir something in a clay pot resting near the coals. The scent of meat and wild herbs drifted into the air. Lucy’s stomach turned on itself. He glanced over his shoulder. “You hungry?” She nodded. He ladled stew into a small wooden bowl and brought it to her. She took it with a quiet thank you and ate slowly. The broth was thin but warm. Bits of rabbit, wild carrot, and something green she didn’t know.

“You’re not from the camp,” she said after a few bites. “No. Do you live here?” He nodded. “Off and on. Alone.” Another nod. Lucy set the bowl down. “I’m sorry I brought trouble.” “You didn’t,” he said, then paused. “Yet.” She looked up sharply. “So, you ran,” he added, tone neutral. “Your boots were city-made, dress torn at the hem, frostbite starting in both feet. You left fast.” Lucy didn’t answer. “I’m not asking,” he said, “just saying.” She pulled the blanket tighter. “I couldn’t stay.” He didn’t press. Instead, he stood and moved to the curtain, pulling it back just enough to look outside. Wind howled beyond the stone. Snow fell sideways. “You’ll need to stay until the storm passes,” he said. “Two days, maybe three.” She nodded. “Thank you.” Reed turned. “You don’t owe me.” But Lucy wasn’t so sure. In her world, nothing came free.

Later, as the storm deepened and night pressed in, she lay beneath the heavy furs, listening to the wind scream against the mountain side. Reed sat near the fire, carving something from a piece of wood. He hadn’t spoken in hours, and yet she felt safer than she had in years. Before sleep took her, she whispered one last thing. “Why do you live out here?” He didn’t look up. “Same reason you ran,” he said. “Some places ain’t safe for people like us.” And the fire burned on.

The snow let up on the third morning, but the cold dug in deeper, like it had made up its mind to stay. Outside the shelter, the world had turned bone white and silent. No wind, no tracks, just stillness. Inside, the fire had burned low. Reed stirred the embers, coaxing new flame from the coals. Lucy watched his every movement, how he moved without sound, how nothing he did was wasted. She was beginning to understand his language wasn’t built of words.

“You always live alone?” she asked softly. Reed glanced her way. “Mostly.” She hesitated. “Doesn’t it get lonely?” He didn’t answer, just added more wood to the fire. That was answer enough.

They shared breakfast—salted venison, hard bread, pine tea. The tea tasted like chewing on a tree branch, but it warmed her chest and cleared her head. She sipped slowly, watching the way Reed kept glancing toward the entrance. “You expecting someone?” she asked. He shook his head. “Always expect something.” Lucy tucked her knees beneath her. “My stepfather wouldn’t look for me, not unless someone offered him coin to do it.” Reed didn’t respond, but the flicker in his eyes said he understood the kind of man George Harland was without needing details.

After the meal, Reed stepped outside to check his snares. Lucy, left alone in the shelter, ran her hands along the grain of the wooden floor, rough but solid. She studied the items he kept tucked into shelves, bundles of dried herbs, a gourd full of what smelled like bear fat, strings of beads, feathers, a carved bone flute. Each object felt like a piece of a life she’d never been shown before. A life not written in books, not shouted from pulpits. Something older, quieter.

Reed returned with a brace of rabbits and a dusting of snow across his shoulders. “Show you something,” he said, tossing the rabbits onto the skinning rack. He led her out past the rocks, up a narrow trail between fir trees, frosted like wedding lace. The trail ended at a clearing with a small pool, frozen around the edges, steam rising from the center. “Hot spring,” he said. “Been here longer than any name ever given it.” Lucy stepped close, kneeling to touch the warm water. “It’s beautiful.” He nodded. “Used to come here with my mother. She said, ‘The water remembers.’” “Remembers what?” He looked toward the trees. “Whatever’s left unsaid.”

They stood there a while, not speaking, just breathing, just listening to the forest stretch and groan under the weight of winter. Back at the shelter, Reed showed her how to prepare rabbit meat, how to twist sinew into thread, how to identify the healing roots he kept stored in a clay jar marked with red ochre. “That one is for fevers,” he said, pressing a knuckle gently against a root shaped like a curled finger. “Willow bark for pain. Yarrow to stop bleeding.” Lucy listened, repeating the names softly. She wanted to remember.

That night she offered to help with dinner. Reed handed her a flat stone, a handful of wild tubers, and a battered carving knife. “You stir the pot too early,” he said, half-smiling, “you burn the bottom.” She grinned. “I’ll try not to disgrace your stew.” “Too late,” he murmured, and turned to clean the rabbits.

They worked side by side, not needing to fill the space with chatter. The fire crackled. Snow fell outside in slow, slanting sheets. As they ate, Lucy spoke quietly. “When I was little, my mother used to sing while she cooked. Songs I didn’t know the words to.” “What kind of songs?” “The far ones. Foreign, not English, not even like hymns. I asked once what they meant. She just said, ‘Old things.’” Reed looked up. “You remember any?” Lucy hummed a few bars. The tune was light and lilting. Reed’s face changed. He didn’t smile, but his gaze grew far away. “My aunt used to sing that,” he said finally.

Lucy’s breath caught. “Was your aunt…?” He nodded. “Apache. My mother, too. My father was Mexican. He left before I was born. I never knew.” Lucy whispered about her mother. She died when I was ten. She didn’t talk much about before. Reed studied her face. “You carry her voice. That’s enough.” She blinked hard, the words landing deeper than she’d expected.

Later that night, after Reed had settled onto his bedroll and the fire burned low, Lucy sat awake. She reached into her bundle and pulled out the locket, opened it again. Inside was the same worn thread tied in a loop. She ran her thumb along it, wondering what it meant, what it connected her to. She glanced over at Reed. He was still, breathing slow. A man carved from silence. She spoke into the quiet. “Why do you trust me?” A long pause, then, “I don’t.” Lucy smiled a little. “Fair.” Another pause. “But you’re not lying,” he added. “Not to me. That counts for something.” She leaned back against the wooden wall, eyes fluttering shut. And somewhere in the hush between heartbeats and snowfall, a strange peace settled over them both.

The next morning, the sky opened blue and cloudless, as if winter had spent itself in the night. The snow sparkled like crushed glass under the pale sun. Reed stepped out early to check traps, leaving Lucy alone with the slow-burning fire and the quiet throb of her thoughts. She had slept lightly, the kind of sleep where dreams ran just beneath the surface, like pulse beneath ice. In one of them, her mother had stood at the doorway of their old house, humming that same tune, her hands wrapped around a bowl of something steaming. Lucy woke with the scent still lingering.

She stirred the fire and noticed a small leather pouch sitting on the flat rock beside her blanket. She hadn’t seen it before. Carefully, she untied the rawhide cord and opened it. Inside was a fine gray powder, fragrant and earthy, mixed with tiny shavings of cedar bark. A sliver of bone lay nestled among it. She held it up to the light. It wasn’t just ash. It was ceremonial.

Reed returned not long after, boots wet with melted snow and three hares strung over his shoulder. He paused when he saw her holding the pouch, then set the game down and knelt beside the fire. “You left this,” Lucy said softly. “I did.” “What is it?” He didn’t answer right away. He reached into the pouch and took a small pinch of the ash, then sprinkled it over the coals. The fire flared gold for a breath, then returned to steady red. “It’s called chi ash,” he said. “Spirit ash, burned herbs, cedar, pieces of our dead. We keep it for ceremony, for memory.” Lucy stared at the remaining ash in her hand. “You’re giving this to me?” Reed looked at her steady. “It’s not a gift. It’s a recognition.” She swallowed hard, unsure what to say. “Why me?” He didn’t look away. “Because you stayed when you could have run again. Because you listen. Because the fire doesn’t lie.” Lucy closed the pouch carefully, reverently. Her hands trembled just a little.

That afternoon, they sat near the edge of the clearing where the sun warmed a patch of stone. Reed carved something from antler while Lucy wove a small cord from rabbit sinew, learning the motion from memory and watching his hands. “You always make things?” she asked. He nodded, “Keeps the ghosts quiet.” “Does it work?” He gave the smallest smile. “Sometimes.” She watched the way the light caught in his hair, the way his fingers moved with purpose. There was something quiet in her chest, a warmth not from the fire or the sun, but from knowing she was no longer invisible.

She hesitated, then said, “Reed… I can’t stop thinking about what you said. That the thread in my locket might be from your people. That my mother might have been one of you.” He nodded once. “Is there a way to know?” “Not with words,” he said. “Not always. But with songs. With how a hand moves over earth, with how someone speaks to fire.” She looked down at her palms. “That’s not much to go on.” “It’s enough.”

That night, as Reed cleaned the hides and Lucy stirred the stew, a wind picked up through the trees, bending them like dancers. The lodge creaked, sparks snapped, and in the hush that followed, Lucy spoke again. “Would your people accept someone like me?” Reed didn’t answer for a long time. When he did, it was slow, careful. “They don’t accept outsiders easy. Not anymore. Too many have come with fire and promise and left graves behind.” Lucy flinched. She understood. She was from that world. But he continued, “If someone carries the blood, if they carry memory, even if they don’t know it yet, that’s different.” She looked up, “I want to learn. I want to remember.” He met her gaze. “Then you will.”

Later, after the stew and the silence had both settled, Lucy sat by the fire with her knees drawn up, her fingers playing with the ash pouch. “I keep trying to forget who I was before,” she whispered. “Back at the camp, I was quiet, obedient. I thought that was how I’d survive. I let myself be small.” Reed turned toward her, his face lit only by the firelight. “And now?” “I don’t know. I’m still scared. But here with you, I don’t feel like I have to be small anymore.” He said nothing. But after a moment, he reached into the dirt beside him and began to draw. His finger moved slowly, pressing lines into the soft ground. A circle, then a figure, then a flame inside the figure’s chest. He looked up. “This is you.” She leaned forward, studying it. “Why a flame?” “Because you didn’t beg,” he said quietly. “You burned.” Lucy swallowed against the tightness in her throat. “Reed…”

He stood, brushing the dust from his hands and walked to the doorway. For a long while, he said nothing, only stared out at the trees bending in the wind. Then he said, voice low and even, “I can’t control myself around you.” The words hit her like the snap of firewood. She rose slowly, her hands stilling at her sides. “What do you mean?” He didn’t turn. “When you laugh, when you sit by the fire and look at me like you see more than a shadow, I forget how long I’ve been alone. I forget why I chose it.” He turned then, his eyes dark, but not cold. “I don’t mean I’ll hurt you. It’s not like that. It’s just… when I’m near you, I want to be more than what I’ve been.” Lucy stepped closer, barely breathing. “Then be.” He searched her face as if trying to memorize it. Then nodded once.

That night they didn’t touch. They didn’t need to. But between them the fire burned brighter than it ever had.

.

play video: