Japanese Women POWs Braced for Execution at Dawn — Americans Brought Them Breakfast Instead

“A Breakfast Instead of Death: How American Soldiers Changed the Fate of Japanese POW Women”

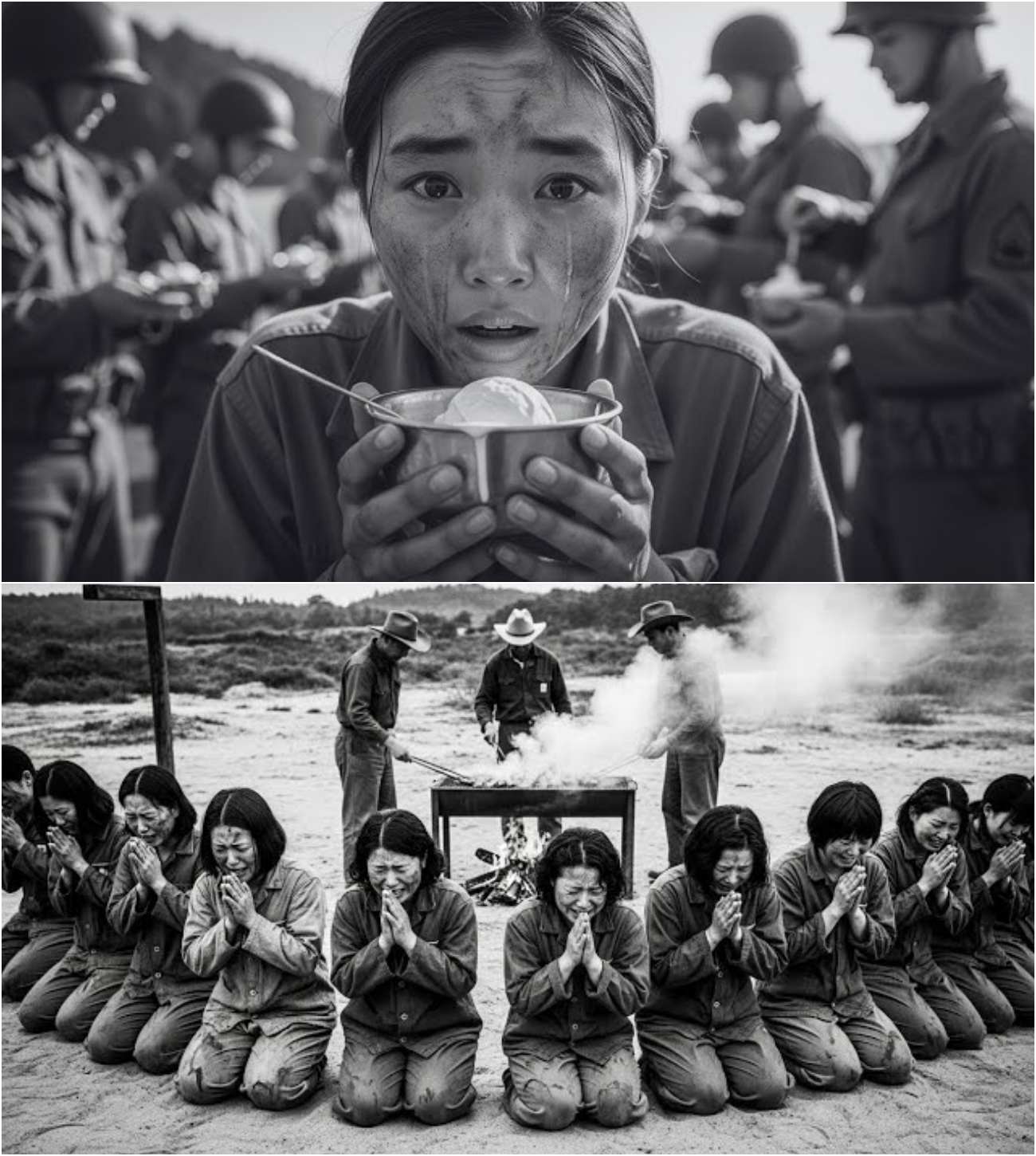

April 12, 1945. In the muddy, makeshift compound outside Baguio, Philippines, 24 Japanese women prisoners of war knelt in the dirt, their hands clasped in silent prayer. They were not praying for salvation. They were praying for death.

For the last three weeks, these women had lived in constant fear. Captured during the final stages of the war in the Philippines, they had been abandoned by their country, forced into hiding, and caught in a desperate struggle for survival. As American forces closed in, the women had expected their fate to be swift and brutal: execution at the hands of the enemy. Their minds were filled with images from propaganda films and radio broadcasts, showing American soldiers as merciless monsters who showed no mercy, no humanity.

But what happened next shattered everything they had been taught to believe.

As the sun rose on that fateful morning, they heard the heavy, purposeful footsteps of American soldiers approaching their compound. The women closed their eyes, steeling themselves for the end. But when the gates opened, the soldiers did not bring rifles or bayonets. Instead, they brought food crates, medical supplies, and blankets. The women froze in shock. The death they had expected was replaced by something far more unsettling—kindness.

This moment, when 24 women from a captured enemy force were treated with compassion by the very soldiers they had been taught to fear, is a story barely told in history. The names of these women are not in major textbooks. Their faces are not dramatized in films. Yet, their experience is a profound reminder of the persistence of human decency, even in the darkest hours of war.

To understand the gravity of this moment, we must first understand the women’s mindset, shaped by years of brutal military propaganda. Japanese military culture in 1944 was unyielding in its stance on surrender. The Senzhenkun, the military code, emphasized one key rule: “Do not live to experience shame as a prisoner.” Japanese soldiers were trained to take cyanide capsules or to use grenades on themselves rather than surrender. For women in military service, the stakes were even higher—surrender was seen as the ultimate disgrace.

By March 1945, as American forces pushed deeper into the Philippines, the Japanese defensive positions were collapsing. Among the Japanese forces were a small group of women—nurses, administrative staff, and communication officers—who had found themselves cut off from the main army. They were hidden in the hills, surviving on foraged roots and contaminated water. Starving and exhausted, these women had resigned themselves to the belief that death was the only escape from their suffering.

Sergeant Macho Tanaka, a 31-year-old nurse, kept a diary throughout this time. On March 28th, she wrote, “We have no food, no medicine. Fumo is burning with fever. At night we hear American patrols passing nearby. Each night I think tomorrow they will find us. Tomorrow it ends.”

On April 1st, 1945, their capture came not with violence but with exhaustion. An American patrol discovered them in a collapsed warehouse. Private First Class Robert Chen, an interpreter, recalled the scene in a later interview: “They were huddled together like frightened animals. Their uniforms were torn. Some were barefoot. When they saw us, they didn’t run. They just closed their eyes and started praying. I thought they were praying for mercy. Later, I realized they were praying for death.”

The women were transported to a temporary detention compound on the outskirts of Baguio. It wasn’t a traditional POW camp—there were no established facilities, just a guarded perimeter, a few tents, and a basic water source. Their rations were minimal—rice porridge, occasionally supplemented with dried fish. They were convinced this meager food was a cruel joke, designed to fatten them up before their execution.

For the first week, the women barely touched their rations. Their belief in the propaganda that Americans were merciless killers overshadowed everything else. They were convinced that any kindness shown was part of a twisted game meant to lull them into a false sense of security before the real punishment began. As Fumiko Sato, one of the nurses, recalled later, “We thought they were playing with us like cats with mice. We waited each day for the game to end.”

Then, on April 12th, everything changed.

Captain William Morrison, a 34-year-old history teacher from Portland, Oregon, and a seasoned combat veteran, was assigned to inspect the compound. What he saw that morning broke through the emotional armor he had built during the war. These were not enemy soldiers. They were starving, frightened women who looked as though they had already died inside. He could see the fear in their eyes—their belief that mercy was not possible.

Morrison made a decision that would change everything.

Turning to his supply sergeant, he ordered, “Get me breakfast. Real breakfast. Everything we’ve got.” Within an hour, the soldiers returned with crates of fresh bread, canned meats, fruit cocktail, coffee, and chocolate bars. As the crates were opened in the middle of the compound, the first thing that struck the women was the smell. A smell they hadn’t experienced in months. Fresh bread, the savory scent of cooked meat, the sweetness of fruit.

As one of the women, Sergeant Mitcho, approached the crates, she picked up a can of corned beef and examined it closely. She turned to Captain Morrison, asking through the interpreter if the food was poisoned. Morrison opened the can with his knife, took a bite, and handed it back to her. “Tell her it’s real,” he said. “Tell her they’re not going to die today.”

At that moment, the dam broke. The women surged forward, not frantically, but with a deliberate calm, as if savoring the act of eating something that might vanish at any moment. Some of the women ate right there in the dirt, while others brought food back to the sick women who couldn’t stand. For them, the food was more than just sustenance—it was a symbol of survival. Private Yuki Harada, only 19 years old, picked up a chocolate bar and held it as if it were a sacred object. She later recalled, “I thought I was dreaming. I thought I had died and this was some kind of afterlife.”

In the days that followed, the transformation was both physical and psychological. The women began to regain strength. Their faces, once gaunt and hollow, filled with color. They began to eat regularly, and the tension that had gripped them began to ease. They started to trust their captors, seeing the Americans not as their enemies, but as human beings capable of compassion.

Captain Morrison didn’t stop at food. He requisitioned medical supplies and ensured that the women received proper care. He had no obligation to do so; the women were technically prisoners of war, subject to military regulations. But Morrison recognized something fundamental: they were human beings, not just the “enemy.”

The psychological shift was more gradual, but equally significant. Lieutenant Yoshiko Nakamura, the highest-ranking officer among the women, had spent years in the military, conditioned to uphold the honor of the emperor and lead her troops with unwavering discipline. But what was honor when your enemy fed you? What was discipline when your own military had abandoned you?

The truth of the situation was undeniable. The women had been lied to for years. They had been taught that the Americans were monsters, that they would be tortured and murdered without mercy. But here they were, being treated with respect, receiving medical care, and eating food they had never imagined they would receive from their captors. This wasn’t just a change in their circumstances—it was a change in their understanding of the world.

For the American soldiers, the encounter also presented a moral dilemma. These were the same soldiers who had lost brothers, cousins, and friends to the Japanese war machine. But they also recognized that these women were not the faceless enemies they had been led to believe in propaganda. They were people, just like the soldiers they had left behind at home.

By the end of April, something extraordinary had developed at the compound—not friendship, not quite that—but recognition. These women were no longer enemies. They were people who had been forced into a war they didn’t choose. The guards had begun teaching them English, and the women had started teaching the soldiers Japanese phrases. They shared stories, played cards, and even learned each other’s songs. It was a quiet, incremental process of healing—one that transcended language barriers, military uniforms, and national borders.

When the war in the Philippines ended, and the Japanese women were finally repatriated, the impact of their experience stayed with them. They had been captured by the enemy, but the enemy had shown them something more powerful than victory: humanity.

As the women returned to Japan, they carried the memory of the kindness they had been shown—of being treated as human beings rather than enemies. They shared this story with their families, explaining how the Americans had fed them, healed them, and treated them with dignity, despite the war and the animosity between their countries.

Their story is a testament to the power of compassion in the darkest hours of war—a reminder that even in total conflict, humanity can survive, and sometimes, it is the simple act of offering food and kindness that makes all the difference.