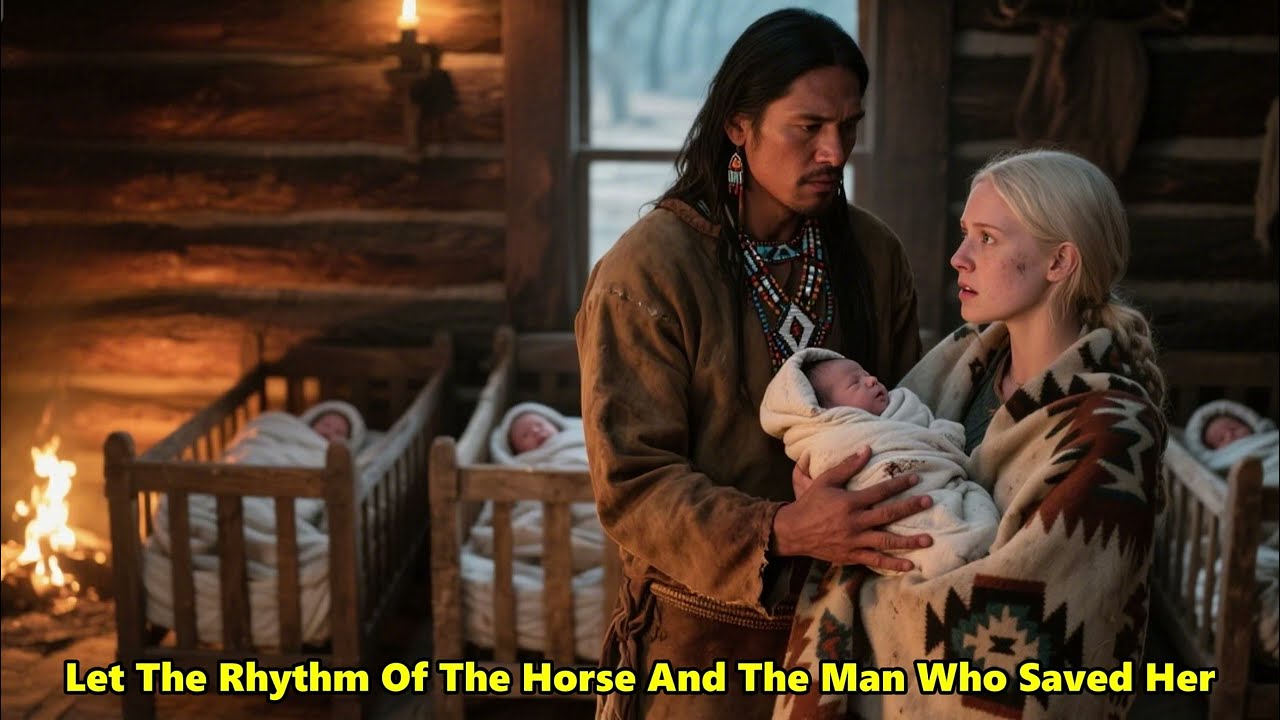

Buried to Her Neck for Infertility—Until Apache Widower with Four Kids Dug Her Out and Took Her Home

.

.

.

Buried to Her Neck for Infertility—Until an Apache Widower Dug Her Out and Took Her Home

The wind didn’t weep for women like her. It passed over Sadi Thorne’s brow as if she weren’t there, lifting bits of sand into her lashes, teasing the single curl clinging to her cheek. The sun had gone down hours ago, taking with it the heat and leaving only the chill that comes when hope has already drained out of the day. Sadi blinked slowly, her eyelids grainy and heavy with dust. She couldn’t feel her legs anymore—couldn’t remember the last time she’d drawn a deep breath. The earth held her tight from the shoulders down, packed by settler hands and cruel silence just past dawn.

The town hadn’t jeered or called names. No, it was worse than that. They had gone quiet. The kind of quiet you only find when a person’s been declared no longer a person at all. They called it mercy—one night buried up to her neck. “No wolves out this far,” they’d said. “No rain in the forecast. Just a lesson, a warning. Then she’d be free to leave Mercy Ridge, just as barren as when she’d arrived.”

“Infertile,” the midwife had whispered, as if confessing murder. “Hollow as a prairie gourd. I’m sorry, honey.” Sadi had nodded, not because she understood, but because the midwife’s eyes looked more sorry than her own mother’s ever had. The rest unfolded like dry thunder: her husband’s mother folding up the wedding quilt and saying nothing, the preacher frowning at the church steps, her husband Jonas accusing her of hiding the truth. “If you were honest, you’d have let me find a fruitful wife.” Then silence. Then the tribunal.

She didn’t cry during the burial. Didn’t scream—not when they covered her up to the collarbone, not even when one of the boys, Eli Samson, pressed the dirt a little harder than needed around her chest. He’d smelled like whiskey and mint, and Sadi swore she saw something gleeful in the way he patted her down, as if she were already soil.

Now, in the blue dusk, the silence hurt worse than the sand. Her tongue was swollen, her lips cracked. She whispered her own name sometimes, just to remind herself she still existed. Sadi Thorne, twenty-five. Once a girl who loved yellow buttercups. Once a bride with embroidered linens. Now just a buried thing the town wanted to forget.

The stars came out slow. Coyotes called far off, their cries bouncing between canyons. Somewhere close, an owl hooted. Sadi’s breath shortened. Her thoughts wandered—her grandmother’s cornbread, the rhythm of washing sheets, a cradle she’d built once for a friend’s baby out of spare hickory wood.

A shadow flickered across the sand. Her eyes twitched open. At first, she thought it was death: a figure on horseback loomed just beyond her blurred vision, tall and unmoving, half-formed in the haze of moonlight and swirling dust. He dismounted in a single, quiet motion—no town boots, no spurs, moccasins, a long coat, a rifle slung over his shoulder.

She tried to speak but her tongue betrayed her. All that came out was a dry croak and a single tear. The man knelt beside her. In the dark she saw high cheekbones, storm-dark eyes, and a mouth set in a line so steady it soothed her before he’d said a word—though he still hadn’t. He didn’t ask her name. He didn’t ask what she’d done. He didn’t ask why. He just began to dig.

The first handful of dirt scraped aside sent warmth up her spine like fire cracking in a cold hearth. She tried to lift her chin but he placed a hand gently on her brow and shook his head once, slow and sure. It took time. The silence between them filled with breathing, the hush of sand being pulled from its place. He worked methodically—not rushed, not slow—as if this were just something a man did when he saw a woman half-buried by shame.

She gasped when her ribs were freed, coughed hard when the pressure released. He paused, unstrapped a leather flask from his belt and held it to her lips. It was water—cold and honest. She drank in shudders. When her arms came loose she reached out to steady herself against him, but he didn’t flinch. His skin was warm, his grip steady. By the time her hips and legs were uncovered, her breath had steadied enough to speak.

“Why?” she rasped.

He looked at her for a long moment. “You’re cold,” he said, voice like the inside of a drum, low and round with the weight of old sorrow. “Not dead.” He stood, went to his horse, and returned with a blanket—not wool, but deerskin, supple and lined with faded symbols. He wrapped it around her shoulders, then lifted her as if she weighed no more than a bedroll. She clung to him—not out of fear, but because something in her had cracked open, something old and full of tired silence. She pressed her forehead to the side of his neck. He smelled like smoke and cedar.

“Name’s Taza,” he said softly as they rode through the night. “Lone Tree Clan.”

She didn’t answer. Her jaw hurt, her body ached, her mind was drifting. But her heart whispered something it hadn’t dared in weeks: “Not alone.”

The land around them darkened as they climbed higher—a narrow trail toward a ridge where trees stood tall like watchers. The horse moved sure-footed beneath them. Taza held the reins in one hand, the other around her waist—not tight, not possessive, just enough to keep her steady. She leaned into him as the wind picked up again. This time it wasn’t cruel, just curious. It rustled the hem of her blanket, whistled past her ear, stirred the braid that had come half loose. She closed her eyes. The world rocked gently beneath her.

She heard the faint cooing of babies on the wind—imagined or real, she couldn’t yet tell. But she would know soon, because Taza Lone Tree was taking her somewhere the world might not find her again. Somewhere higher than judgment, warmer than shame—somewhere a woman didn’t have to bleed to prove she was worthy of love.

And in the distance, dawn threatened the edges of the horizon.

The cabin sat on a hill like it had grown from the stone, tucked between two pines that bent in the wind as though keeping secrets. Dawn slid across the earth in quiet ribbons, brushing the frost off fence posts and catching on smoke rising from the chimney. The trail behind them had vanished under hooves and time. No one had followed. Not yet.

Sadi didn’t remember falling asleep, only waking curled beneath a buffalo hide quilt, the smell of cedar smoke and milk in the air. Her skin still wore the sting of buried dirt, the ache in her ribs like a bruise from memory. She blinked into the soft light. A cradle creaked.

The room was plain—pine walls, packed earth floor, a stone hearth at the far end—but lived in, worn, not unkempt. A carved cradle rocked near the stove, and from within it came a soft, mewling cry that cracked like frost underfoot. She sat up, the blanket sliding from her shoulders. Across the room, the man from last night knelt at a second cradle, lifting a swaddled infant with the care of someone who knew how to be still. He glanced at her once—not startled, not warm, just seeing her the way men sometimes see wind shifts or wolves on the ridge. Present, not threatening, not to be named yet.

He passed the child to her without a word. The baby was no more than a few weeks old. Big, dark eyes blinked up at her like stars submerged in water. Sadi hesitated, hands half open. The child squirmed, rooted for something.

“She won’t take the bottle this morning,” the man said, voice as even as last night’s wind. “Thinks I’m her mother. She’s wrong, but I don’t tell her so.”

Sadi took the child carefully, a muscle in her arm trembling from the effort. The baby smelled of talc and something faintly sour. Her lips found the skin of Sadi’s wrist and nuzzled.

“I’m not her mother either,” Sadi murmured.

The man said nothing, only turned back to the stove and poured something thick and brown from a tin pot into a carved wooden bowl. He handed it to her—porridge with crushed wild berries. Not an apology, not a kindness wrapped in guilt, just a quiet act between two people who hadn’t yet agreed to be anything at all.

“You live alone?” she asked after a few bites.

“Not anymore.”

She didn’t ask how many children there were. The cabin answered that: two cradles, a small cot in the corner, and a basket swaddled tight in furs near the fire. Four in all—two sleeping, one in her arms, one somewhere just out of sight, judging by the faint fussing sound behind a drawn curtain.

“I’m Sadi Thorne,” she said after a pause, as though remembering herself.

He nodded. “Taza.” Names were enough, perhaps. Words were weight in a place like this.

Outside, snowflakes began to drift, thin and unsure of themselves. Early winter. She rose, baby still against her chest, and walked to the window. The ridge looked endless. The town far below, the road back invisible.

“They’ll come looking,” she whispered.

“No one’s looking for you,” Taza said, without cruelty. It was true. Sadi knew it in her bones. The men who’d buried her did not plan to return. They had already crossed her name out of their ledgers. Even Jonas, her husband—he’d likely told the town she’d wandered off in shame.

“Why did you bring me here?” she asked, softly, as if she didn’t quite want the answer.

Taza’s eyes flicked up, slow and measured. “You were still breathing. That was all.” And somehow it was enough.

The baby in her arms fussed. Sadi began to hum without thinking—a tune her mama used to sing when storms rattled the roof. The child quieted, cheek pressed to Sadi’s collarbone. She didn’t know what part of her began to unravel first—the ache, the silence, the fear. But something inside her cracked open like thawed ground, and for the first time in weeks, warmth seeped in.

She stayed.

The first day passed like a shadow. Meals, bottles, wood stacked by the door. Taza didn’t speak unless needed, and when he did, his voice was like riverstone—steady, shaped by old grief. Sadi washed what she could—linens, tiny clothes, an old shirt of his that had dried stiff with sweat and salt. The water near the slope was half frozen, but her fingers worked through it anyway, numb and raw. At night, the babies cried. They didn’t cry for her, but she answered anyway.

She learned their names not from words but from tones—the deep grunt of the oldest boy, the gurgling sigh of the smaller twin. Taza’s hands were too large for some tasks. She watched him try to tie a cloth diaper and fail twice before silently taking it from him. He did not thank her. She didn’t need it. What grew between them was not kindness—not yet. It was rhythm, an unspoken truce between two people carrying what others had buried them beneath.

The second night, she dreamed of dust. But this time, someone brushed it from her skin with gentle hands. In the morning, she found a rough woven shawl folded by her bedside—a patchy weave, earth-colored, heavy on the shoulders. She ran her hand over it and didn’t speak.

Later, she sat on the porch, baby sleeping against her, watching the clouds gather like thoughts too large to hold. The trees whispered above. Somewhere in the brush, a fox barked. Taza stepped outside with a cup of chicory and handed it to her. She took it. Their hands touched briefly.

“There’s no debt,” he said.

“I know.” But part of her didn’t. Part of her still thought he might ask for something later—favors, obedience, penance. That was the way of men in Mercy Ridge. Even the kind ones kept ledgers in their eyes.

He didn’t look at her like that. He looked at her like wind looks at prairie grass—present, shifting, inevitable.

When the sun went down that night, she didn’t lie awake wondering if she would be forced to leave. She lay listening to the slow, soft breathing of children and the quiet footsteps of a man who had nothing to prove. It wasn’t safety yet, but it was shelter. And in a world that had buried her for what she could not give, that felt like a kind of beginning.

The days passed like leaves on water—slow, circling, quiet in their drift. Sadi no longer counted them. She moved between cradles and coals, between bottles and boiled linens, as though she’d always belonged to this rhythm. The babies grew sturdier in her arms, their cries sharper, their eyes more knowing. Even the smallest twin, who had come into the world early and angry, now gripped her thumb with defiant strength.

Taza worked without comment. He rose before light, returned near dusk. His boots always wet with creek water or snowmelt, his shoulders lined with pine dust. He brought what was needed—rabbit, dried apples, pine needles for tonic—and left what wasn’t. Sadi watched him move like a man born to silence, someone who carried his grief under the skin where no one could pry it loose.

Sometimes she wondered what kind of woman had loved him before. She never asked, but the signs remained—a weathered doll tucked on a shelf above the hearth, a faded shawl left folded too neatly in a trunk she hadn’t meant to open. And a wooden basket near the fire, cracked at the rim, that she’d instinctively reached to fix until Taza told her not to.

“My wife carved it,” he said. Not cruel, just final. “Leave it as it is.” Sadi nodded. But the moment stayed between them like smoke that wouldn’t lift.

One evening, after the last baby had drifted off and the sky turned indigo, Taza came in from the cold with a fox pelt over his arm and an unreadable look in his eyes.

“They’re speaking your name in Mercy Ridge,” he said. “Heard it in the trading post.”

She stiffened where she stood, hands still wet from washing. “What are they saying?”

He didn’t answer right away. He set the pelt on a chair, unwrapped his scarf. Only then did he speak. “That you took up with a widower, took his children, made a new tribe out of shame.”

Sadi’s chest tightened. She turned back to the basin, though the water had long since cooled. Her hands trembled against the metal rim.

“They said I cursed a good man’s line,” she said after a long silence. “That a woman who can’t make a child shouldn’t take someone else’s.”

Taza watched her quietly. “That what you believe?”

“No.” But her voice caught on the edge of the word, and she hated that he could hear it. “I tried,” she added. “Jonas and I, we tried for near two years. I lit candles, took herbs, prayed. Every time I bled it felt like a death no one could see.” Her shoulders shook. She wasn’t crying—not quite. It was something heavier, something like confession. “They told me I was born broken, that I tricked a man into marrying a dry well.”

Taza stepped forward, his boots slow and deliberate across the creaking floor. He didn’t touch her. He didn’t speak right away, but his nearness held her steady.

“My wife,” he said softly, “was strong. Her body still broke anyway. Giving life doesn’t make a woman whole. Keeping it alive does.”

Sadi turned to him and for the first time in days met his eyes directly. There was no pity in them. Just a shared knowledge of things lost and carried forward anyway.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” she whispered.

“Neither do I,” he said.

That night, she didn’t sleep. She sat beside the fire with one of the babies pressed to her chest, rocking slowly, humming the song her mother used to sing when the rains came late and the crops cried for water. She thought of the basket, of her hands itching to fix what was broken in it. She thought of her womb, silent and stubborn, and of the child now sleeping in her arms.

The next morning, she walked down to the stream with the linens bundled under one arm. The trail was slick with frost, and the cold bit her skin clean. She didn’t mind. It felt honest. Two settler women were already there, kneeling in the shallows. One of them, Annth Clay, glanced up and narrowed her eyes.

“Well if it ain’t the barren bride turned wet nurse,” she said, loud enough for the trees to hear.

Sadi didn’t answer. She dipped her linens in silence, scrubbed slowly, but the words clung like smoke.

“Figures a man like that would take in a useless girl,” the second woman said. “They don’t know better, those people.”

Sadi wrung out the cloth, jaw tight. Her hands were steady, but her breath was shallow.

“What’s he get from you, huh?” Annth pressed. “Can’t be the babies. Those ain’t yours. Can’t be kinship. You don’t even look right in that cabin.”

Sadi looked up and said nothing. She finished her washing, rose with grace, and walked back up the trail with frozen fingers and a spine made of something she didn’t know she had.

That night, she told Taza what happened. “I’ll leave,” she said. “They won’t stop. They’ll come eventually. They’ll say I bewitched your children. That I’ve stolen a place I don’t deserve.”

Taza said nothing at first. Then he picked up the smallest child, held her to his shoulder, and turned toward Sadi. He didn’t speak of justice or defiance or shame. He said, “This one wasn’t breathing right when I found her. You warmed her. You fed her when she wouldn’t feed. She lives because you stayed.”

Sadi didn’t answer. Her mouth moved but no sound came. Her eyes burned. Taza stepped closer and placed the baby in her arms.

“Let them talk,” he said. “The land knows better.”

She stood there a long time, the baby curled against her, and something inside her shifted, slow and deep, like snow beginning to melt after too many months of cold.

Later that night, when the babies were quiet and the fire had sunk into coals, she returned to the basket. She didn’t mend it. She lined it with fresh cloth, tucked in one of the twins, and set it back near the hearth—not to replace the past, but to hold what still had life. And in the hush that followed, she felt the cabin breathe around her—not as a place she had borrowed, but as a place that might, in time, belong to her.

The wind smelled of ash before the flames ever showed. Sadi had just settled the twins into the cradle Taza carved from a cottonwood log. The air outside crackled with the kind of tension only fire or fear could bring. The baby stirred as she bent to tuck the blanket higher, restless, too quiet. Even they seemed to sense the shift.

Taza stood at the doorway, rifle in hand, back straight as pine. He wasn’t looking at the sky, though it burned orange far beyond the trees. He watched the trail below the ridge, where hoofbeats rolled like distant thunder and torchlight moved between the trees like swarming fireflies.

“They’re coming?” Sadi asked, though her voice held no question.

He didn’t turn. “Ten, maybe more. Lanterns. Axes.”

Her mouth went dry. Mercy Ridge. They never liked questions they couldn’t bury.

Sadi swallowed hard and moved to the cradle, pressing her palm against the soft fuzz of a baby’s head—four children, a home made of gentleness and grit, a man who had once knelt in the dirt just to free her. Now they wanted to set it all to flame.

Outside, the dogs barked low and long, their voices like tolling bells. The pine trees whispered warnings as the wind grew restless. Sadi crossed the room, pulled the curtain back from the basket beside the hearth. She lifted the smallest, wrapped her in two shawls, and kissed the tip of her nose. Then the next child, then the next. No panic in her hands, only urgency shaped by love.

Taza laid the rifle across the table. “We have minutes.”

“Should we run?”

“No time. Too many small feet. Too much cold.”

Sadi nodded. She moved fast but quiet, pulling up the floorboards behind the stove. Beneath it, a small crawl space no bigger than a coffin waited, lined in dry wool and pine needles. He built it months ago for emergencies—for a world that didn’t forgive certain sins, like being born native, or barren, or brave in the wrong ways.

She laid the babies down gently, one after the next. They whimpered but didn’t cry, as if they understood. When she rose again, Taza had lit the lamp low. His knife gleamed on the table beside it. He’d removed his coat and stood in his undershirt, scars along his arms like rivers etched in skin. Sadi grabbed the poker from the fire. Her fingers trembled only once.

Outside, the footsteps grew louder. A voice rang out. “We know she’s here, Lone Tree! Bring her out.”

Taza didn’t answer. The men circled the house like vultures, shouting. “Now she’s cursed the babies! The Apaches bewitched! Let’s smoke her out—we’re cleansing the sin!”

A rock hit the cabin wall with a thud. Then another. Sadi stepped to the window and pulled aside the curtain. Men she knew stood there—Eli Samson with a torch high in hand, Mr. Clay drunk and wild-eyed, the preacher’s cousin, coat buttoned all wrong. They weren’t law—just fire and fear dressed in righteousness.

She turned to Taza, her throat dry. “They’re not going to wait.”

He stepped forward, took her face gently in both hands. His eyes held no panic, only sorrow. “Let them see what mercy really is.”

He opened the door before she could stop him. The wind caught his hair, lifted the smoke into spirals. Silence fell as he stepped out, empty hands raised. Sadi stayed in the doorway, shadow just close enough to hear.

“She’s under my roof,” Taza said. “She’s done no harm. She’s yours now.”

Eli sneered, stepping forward. “Barren comes up the hill now. You keep her like a prize. She bewitched you. Them babies ain’t right.”

“They’re fed. They’re warm. They’re alive.”

Mr. Clay raised his torch. “We don’t want her dead, Lone Tree—just gone. We don’t let bad seeds spread.”

Sadi stepped out. Her voice wasn’t loud, but it cut like frost. “You buried me once, Clay. This time I walk out on my own.”

They turned, startled by her presence. Even the torchlight seemed to hesitate. Sadi moved beside Taza and took his hand—not from fear, but defiance. The firelight painted her face in golden shadow. She looked every part the ghost they tried to make her, only she hadn’t stayed dead.

“You think a woman who can’t bear a child has no worth?” she said. “But I’ve held four in my arms and rocked them to peace.”

“You speak of peace,” Eli spat. “But look what you bring—division, sin, trouble.”

Sadi’s eyes glinted. “You came here with fire. I brought nothing but milk and songs.”

The silence was long and strange. Someone near the back—maybe young Tom Brooks—murmured, “She ain’t wrong.” The preacher’s cousin shifted. The torch dipped slightly. Taza stepped forward again, voice even as stone.

“You can leave now, while your hearts still remember how to.”

They didn’t speak—not right away. The fire cracked. The wind groaned through the pines like an old widow. Then Eli’s scowl turned. “This ain’t the end.” He walked off. One by one, the others followed. Clay lasted, tossing his torch into the snow where it hissed and died.

The darkness returned. Sadi let out a breath she hadn’t known she’d held. Inside, the babies began to cry. They went back together, her hand in his. No one spoke for a while. The only sounds were tiny wails and the rustle of the blanket as Sadi drew the children out of hiding, one by one, her fingers trembling now—but only from love.

Taza relit the fire, adding wood in silence. Sadi held the smallest girl close to her chest, rocking slowly. The scent of smoke clung to her braid. She didn’t care. Taza sat beside her, his hand brushing hers.

“They’ll come again,” she said softly.

“They won’t find you buried this time.”

She leaned into him, forehead against his shoulder. “I don’t want to run anymore.”

“Then stay.”

The snow fell soft outside, covering the tracks, the torches, the echoes. And somewhere beneath all that quiet, something steady began to bloom.

Spring came with its quiet, stubborn grace. Snow retreated into thirsty soil, and small green shoots peeked from the hard earth like secrets whispered too long in the dark. The cabin on the ridge no longer looked like a place to hide. It looked like a place that had endured, like the people inside it.

Sadi stood barefoot on the porch, the morning sun warming the hem of her skirt. One of the twins, Lena, tugged at the lace edge, wobbling on unsteady legs. Sadi bent, caught her before the girl tumbled, and kissed the soft crown of her head. She could barely believe how fast they’d grown. The days had folded into one another like warm quilts, stitched together with feedings, night cries, laughter too quiet to disturb sleeping mouths.

And though Taza still didn’t speak much, his silences now held a kind of comfort. They’d become fluent in glances and gestures, the hush of things that didn’t need words to be understood.

Sadi moved inside, scooping another child up from the rug. Tomas, the oldest, handed her a fistful of pine cones like treasures, his smile crooked and proud. She placed them on the mantle beside the wooden cradle that had once held him and now stood empty—no longer needed, but never forgotten.

The town hadn’t returned—not since that night the flames dared the ridge and lost. Still, whispers trickled up from Mercy Ridge like the last trails of smoke. Taza heard them when he brought trade goods into town. “The witch woman still up there,” they muttered, “made herself queen of bastards and blankets.” Some said she wore black and red omens and creek stones. Others said Taza had taken her as a fifth child—a crippled one.

Sadi heard none of it herself. She didn’t need to. Gossip no longer dug into her the way it once had. Her worth wasn’t held in others’ mouths anymore. It lay in the steady rise of tiny chests as they slept. It pulsed in the soft patter of four small pairs of feet. It rooted itself in the man who watched her as she boiled pine for cough tonic, his eyes gentle, hands busy carving new spoons from old limbs.

That morning, as the children played with pebbles outside, Taza approached the porch with something wrapped in hidecloth. She looked up from her stitching.

“What’s that?”

He said nothing at first, just sat beside her and unwrapped the bundle. Inside was a cradleboard, freshly carved, beautifully shaped, edges still smelling of oil and cedar.

Her breath caught. “You’re making another?”

His gaze didn’t rise. “You said the twins outgrew theirs.”

A pause stretched between them, then snapped tight. She swallowed. “But four is enough.”

He finally looked at her. “Is it?”

The air stilled. Sadi felt her hands begin to tremble, just a little—not out of fear, but out of knowing. He didn’t ask with grand words or declarations. He didn’t kneel, didn’t beg. He simply made space.

She set her stitching down slowly. “I thought you’d never ask.”

That night, as fireflies blinked between the porch rails and the children drifted to sleep, Taza brought her his mother’s ring—smooth silver, once part of a belt buckle. He didn’t place it on her finger. He let her take it herself. Fit.

The next weeks moved like honey—sweet, golden, unhurried. Sadi planted herbs along the slope. She painted the cradleboard with ochre and soot. The babies began calling her “mama”—some stumbling, some with clarity that made her eyes fill with water. Not because she had claimed the word, but because they had.

And then, one late afternoon, the final threat of her old life returned. A rider came up the ridge. Sadi saw him before Taza did. She was hanging linens when the figure appeared near the bend, dust trailing behind his horse like smoke from a dying fire. The man dismounted carefully. His coat was city-worn, hat too clean. His face, older than she remembered but unmistakable, was lined with the guilt of someone who’d hoped never to look back.

“Jonas,” she said, standing still, wind tugging at her apron.

He removed his hat, fumbled with it like it might offer redemption. “Sadi,” he said, voice brittle. “I heard you—that you were alive.”

Taza appeared from the woodshed, quiet and tall. Jonas looked at him, eyes narrowing, then softened as he noticed the toys scattered near the porch.

“I came to—” he paused, rubbed his jaw—“I came to apologize.”

Sadi didn’t speak.

“I thought I was right,” he went on. “The church said you were broken. That I needed a wife who could build a family.”

Sadi’s voice was steady. “And did you find one?”

Jonas looked down. “She died last spring. Childbed fever.”

Silence settled like dust. Sadi walked down the steps slowly. She didn’t raise her voice, didn’t cry. She simply stood before him like a woman risen from her own burial.

“I am a mother now,” she said. “You just couldn’t see it.”

Jonas nodded, pain flickering across his features. “I believe you. I was a fool.”

She looked past him to the path, the world beyond, then back to the porch where Taza stood holding the smallest child, one arm wrapped around her like roots around seed.

“You should go,” she said. “Whatever you lost, it’s not here anymore.”

Jonas tipped his hat, his mouth a broken thing. “I hope you find peace, Sadi.”

“I already did.”

When he was gone, she climbed back to the porch. Taza handed her the baby, who curled into her chest without hesitation.

“You all right?” he asked.

She nodded. The child’s fingers tangled in her braid. A sparrow darted across the sky, catching light on its wings.

That night, as the family sat by the fire, Sadi sang an old lullaby she barely remembered learning. The children curled close, breath soft and even. Taza watched her, his hand resting near hers, their pinkies touching. Later, when the house was dark and still, she wrote a note in her ledger—not of loss, but of life.

They said she was buried in shame. But what they missed was this: she rose as their mother. And the world, try as it might, could never bury her again.

play video: