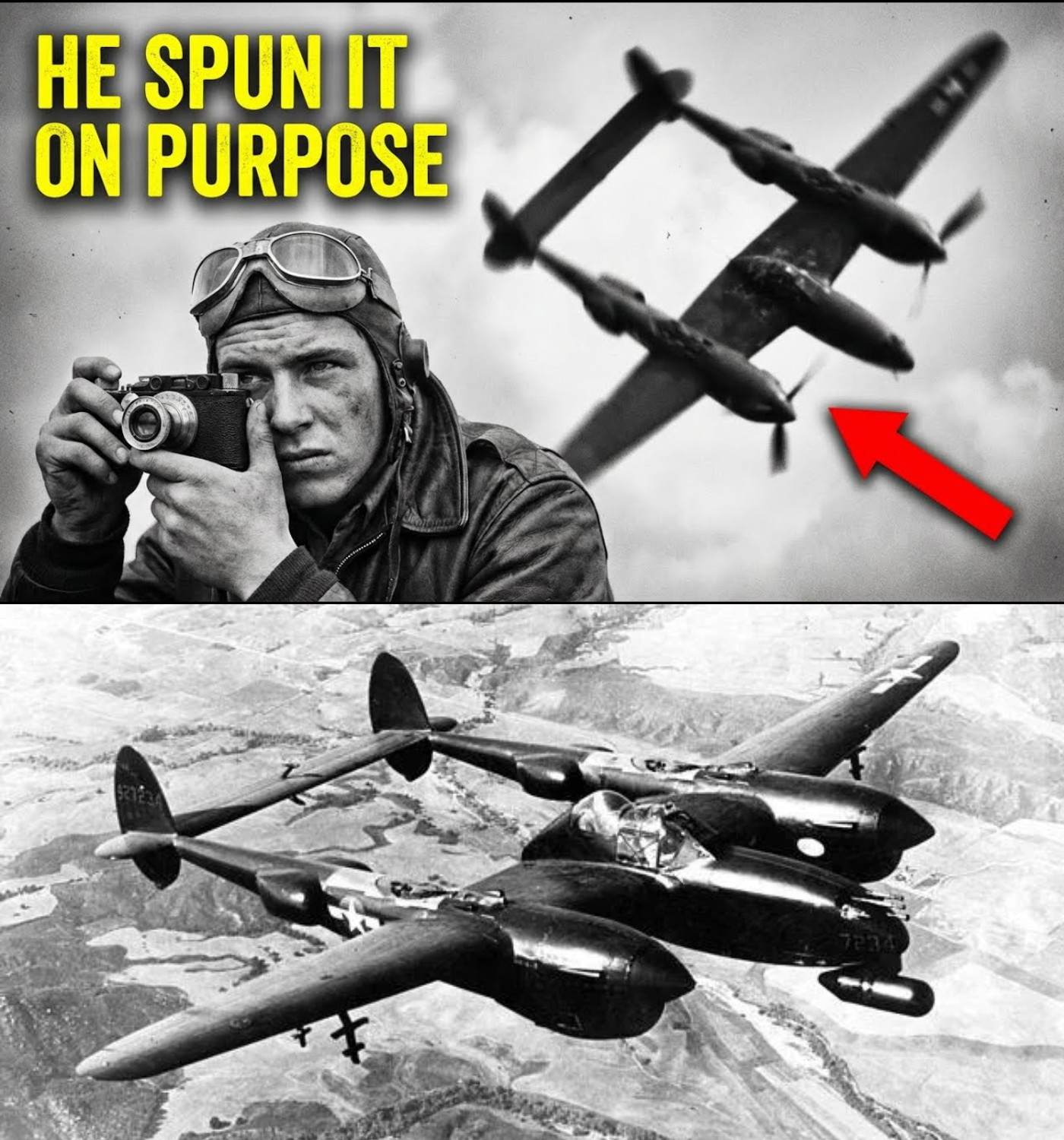

This 18-Year-Old P-38 Cadet Slipped Into a Spin And Discovered a Trick That Outturned 5 Enemy

.

.

The Legacy of Ralph Hoffer

In February 1943, the sun hung low over Muro Dry Lake in California, casting a golden hue across the tarmac where rows of P-38 Lightning fighters stood ready for action. Among the cadets training at Murok Army Airfield was Ralph Hoffer, an 18-year-old with a passion for flight and a mind that grasped the complexities of aerodynamics like few others. Born in Salem, Missouri, Ralph grew up on a farm where he learned to fix engines and understand systems from a young age. His hands were steady, and his intuition for mechanics was unmatched.

But as Ralph and his fellow cadets trained in the P-38, they faced a dark reality. Pilots were dying in training accidents at an alarming rate. The P-38, with its distinctive twin-boom design and powerful Allison engines, was a marvel of engineering, but it had quirks that could prove fatal. The aircraft was designed for speed and altitude, but it also had handling characteristics that were not fully understood. Cadets were warned about spins, particularly the kind that could occur during aggressive maneuvers. If a spin developed, the standard recovery procedures often failed, and the only advice was to bail out if the spin lasted more than two rotations.

Ralph absorbed everything he could about the P-38. He studied its design, watched the mechanics work on the engines, and asked questions that many of his peers would not think to ask. He was fascinated by the aircraft, and he wanted to understand it from the inside out. He soloed after just seven hours of flight training, demonstrating a natural aptitude for flying. But the P-38 was a different beast, and Ralph knew that mastering it would require more than just instinct.

On one fateful day, Ralph found himself at 18,000 feet, executing aerobatics as part of his training. He was practicing energy management, trading altitude for speed, feeling the aircraft’s responses as he maneuvered. But then, in an instant, everything changed. The P-38 stalled unexpectedly, snapped into a spin, and began tumbling through the sky. The horizon turned vertical, then inverted. Ralph had mere seconds to react.

Instinctively, he jammed the yoke to regain control, but the aircraft resisted. The spin intensified, and the altimeter unwound rapidly. He remembered the warnings: if you find yourself in a spin, bail out. But something deep within him hesitated. He recalled the survival accounts of other pilots who had survived spins by doing nothing—letting the aircraft fall and waiting for the moment to recover.

As the world spun around him, Ralph made a decision. He released the controls, idled the throttles, and allowed the P-38 to fall. Time stretched as he waited, heart racing, unsure if he would live to see another moment. Then, as if the aircraft was responding to his surrender, the nose dipped lower, and the spin began to slow. With a gentle nudge of opposite rudder, Ralph managed to level out.

He had survived. But more than that, he had uncovered a profound truth about the P-38. By relinquishing control, he had allowed the aircraft to return to a stable configuration, a revelation that could save lives. Over the next few weeks, he tested this technique, each time confirming that releasing the controls during a spin led to recovery. It was counterintuitive, but it worked.

Ralph documented his findings meticulously, writing a report that outlined his observations and recovery procedures. When he presented it to his superiors, he faced skepticism. The established doctrine was clear: if you entered a spin, you bailed out. But Ralph’s calm demeanor and logical explanations caught the attention of a test pilot named Milo Burcham, who agreed to fly with Ralph to see the technique in action.

On the day of the demonstration, Ralph’s heart raced with anticipation. He executed the spins as he had practiced, and each time, he recovered successfully. Burcham was impressed, and soon after, Lockheed issued a technical bulletin based on Ralph’s findings. The new procedure emphasized neutralizing controls and allowing the aircraft to transition to a nose-down attitude for recovery.

But Ralph’s journey was not without its cost. In July 1944, while leading a flight over Germany, Ralph’s P-51 Mustang was hit by flak. Witnesses saw him attempt a forced landing, but he did not survive. He was just 20 years old, but by then, he had already made a name for himself as a skilled pilot, credited with 15 aerial victories.

Ralph Hoffer’s legacy lived on beyond his tragic end. The spin recovery technique he discovered became a foundational principle in fighter pilot training, saving countless lives in the years that followed. His approach to flying—grounded in logic and an understanding of physics—transformed how pilots interacted with their aircraft.

In the decades that followed, the aviation community remembered Ralph not just as a pilot who died young but as a pioneer who had the courage to challenge established norms. His story became a testament to the power of observation, experimentation, and the willingness to question what was deemed impossible.

Ralph’s name may not appear in every aviation textbook, but among the mechanics, instructors, and pilots who followed in his footsteps, he was a hero. They remembered the farm kid from Missouri who had a knack for fixing things and a mind that understood flight in ways that others did not. His legacy was not just about the techniques he developed but about the lives he saved through his innovation and bravery.

In the end, Ralph Hoffer’s contribution to aviation was a gift of time—the seconds between panic and survival, the moments when instinct could be overridden by understanding. He showed that sometimes, the bravest thing to do when the world spins out of control is to let go and trust in the principles that govern flight. His story continues to inspire pilots and engineers, reminding them that the sky is not just a battleground but a realm of possibilities waiting to be explored.