💡 The Unsolvable Problem: Fueling the Invasion

Following the successful D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, the Allied armies faced a logistical problem so enormous it threatened to stall the entire liberation of Europe: fuel.

In a mechanized war, fuel is the lifeblood of an army. Tanks, trucks, reconnaissance vehicles, and the vast air forces covering the advance all required staggering quantities of petrol. Relying solely on jerrycans, drums, or even tanker ships unloading at captured ports was deemed far too slow and vulnerable to German attack. The sheer volume required—potentially millions of gallons daily—demanded a radical, innovative solution.

The Allied commanders realized that the success of the breakout and subsequent advance across France—the famous “Red Ball Express” of supply trucks—hinged entirely on a continuous, secure supply line that could bypass the bottleneck of heavily defended ports.

The solution came in the form of one of World War II’s most ingenious and daring engineering projects: PLUTO—Pipe-Lines Under The Ocean.

🌊 The Engineering Marvel: Making a Submarine Pipeline

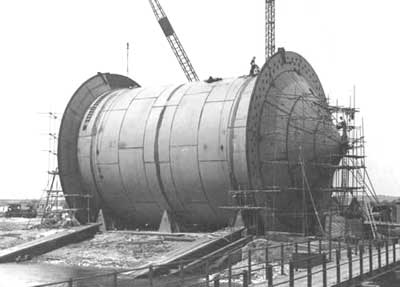

The image provided captures the immense scale of the project: two men stand next to a colossal, semi-circular metal structure. This is not a weapon or a defensive barrier, but a section of a “Conun” (from Continuous Underwater) reel, a massive spool designed to lay the pipeline itself across the English Channel.

The PLUTO concept was the brainchild of Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, and executed by a team of civilian engineers and military personnel led by Major General Sir H. L. “Bertie” Templer. They had to invent the technology from scratch, designing two entirely new types of flexible pipe:

“Hais” Cable (HAIS): Named after the inventors, Hartley, Atkinson, and Siemens, this was essentially a lead-sheathed, reinforced pipe that looked and acted like a thick submarine telegraph cable . It was flexible enough to be manufactured, stored on giant spools, and laid by cable-laying ships without kinking or breaking.

“Hamell” Pipe: Named after the inventors H. A. Hammick and B. I. Ellis, this was a more conventional steel pipe that was welded into long sections and then wound around a massive floating drum called a “Conun” reel—the type of structure shown in the photograph. These reels were towed across the Channel, unwinding the pipe as they went. The largest Conun drums were the size of small ships, capable of holding 70 miles of pipe.

The project began its industrial phase long before D-Day, with secret factories in Britain churning out hundreds of miles of pipe and the specialized equipment needed to deploy them. The process was cloaked in absolute secrecy, with all personnel involved adhering to strict non-disclosure oaths.

⚓ Deployment and Operation

PLUTO was planned in two phases:

Phase I: The Short Hop (D-Day +)

The initial pipelines were laid from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg, a route known as Operation BOLI (Bay of Lucerne). This was the longer, more complex route. However, the first practical pipelines were deployed across the Strait of Dover, the shortest distance, from Dungeness (code-named “Dumbo”) to Port-en-Bessin (code-named “Bambino”). This shorter route was known as Operation BAMBI.

The Laying Process: The laying of the pipes was a race against time and the elements. Specialized ships, often disguised or operating under the cover of darkness, towed the giant Conun drums or laid the Hais cable. The entire length of the cable—up to 70 miles—could be laid in as little as ten hours.

The Pump Stations: On the English side, sophisticated, camouflaged pumping stations were established along the coast. These stations pressurized the fuel, sending it under the Channel at high pressure.

Phase II: The Full Capacity

Once the port of Cherbourg was secured and cleared, the longer BOLI pipelines began to be laid, capable of handling much greater volumes. By the time the Allied armies were making their spectacular advance across Northern France—the ‘pursuit phase’ that followed the breakout from Normandy—PLUTO was fully operational.

The operational success was staggering:

Peak Capacity: By early 1945, the PLUTO system reached its peak, delivering an astounding one million gallons of petrol per day across the Channel.

Total Delivery: By the time the war ended in May 1945, PLUTO had delivered over 172 million gallons of fuel, a contribution that historians agree was essential to maintaining the momentum of the Allied push.

⛽ Fueling the Blitzkrieg in Reverse

PLUTO’s success fundamentally changed the logistics of the war in the West. It provided a reliable, concealed, and relatively secure alternative to vulnerable sea lanes.

Supporting the Advance: Without the continuous flow of fuel from PLUTO, the rapid, aggressive advances of General Patton’s Third Army and Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would have been impossible. The fuel kept the tanks of the armored divisions running day and night.

Bypassing Ports: PLUTO’s greatest strategic achievement was enabling the Allies to push inland without being immediately dependent on major port facilities like Antwerp or Le Havre, which were often heavily damaged or defended. It bought precious time for engineers to repair and clear these large ports.

A Weapon of Logistics: PLUTO proved that in modern warfare, logistical innovation is as critical as firepower. It allowed the Allies to sustain their high-speed, mobile warfare, effectively executing a “Blitzkrieg in reverse” that overwhelmed the depleted German forces.

🌟 A Legacy of Ingenuity

The Pipe-Lines Under The Ocean project stands as a testament to the ingenuity of Allied engineering during World War II. It was a logistical solution that was audacious in concept and successful in execution, achieved under immense wartime pressure and secrecy.

The image of the massive Conun reel serves as a visual metaphor for the incredible, often unseen, effort that went into sustaining the forces that fought and won the Battle of Normandy and the subsequent campaign in Western Europe. It was a secret weapon that didn’t fire a single shot, but ensured that the weapons that mattered—the Allied tanks, aircraft, and supply trucks—never ran out of the power they needed to bring the conflict to its victorious conclusion.