Marines Called His Rifle A “Toy” — Until He Hunted 11 Snipers Alone

The “Toy” Rifle That Hunted Ghosts: John George and the Winchester Model 70

At 9:17 a.m. on January 22, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese bunker near Point Cruz, Guadalcanal, his eyes locked through a scope at a banyan tree 240 yards away. The jungle around him was a steaming, rotting mess—visibility measured in feet, death arriving from nowhere. George was 27, an Illinois state champion marksman, but he had zero confirmed kills. The Japanese had 11 snipers operating in the groves, and in 72 hours, they’d put bullets into 14 men from the 132nd Infantry Regiment. The Americans were being hunted by ghosts who lived in the canopy.

John George was the only one crazy enough to hunt them back—with a civilian deer rifle.

The Rifle Nobody Wanted

George’s Winchester Model 70, with its polished wooden stock and Lyman Alaskan scope, looked like something for elk hunting, not war. The army armorer sneered, calling it a toy. His commanding officer wanted him to leave it behind and carry the standard-issue M1 Garand—a semi-automatic marvel, the gold standard of infantry warfare. The Winchester was slow, heavy, delicate, and held only five rounds. In a firefight, it was the wrong tool.

But the jungle of Guadalcanal didn’t care about military logic. The Japanese had retreated into banyan trees, turning them into fortress towers. Snipers climbed up before dawn, tied themselves to branches, and waited all day, invisible. They didn’t need volume of fire—they needed one shot.

The psychological impact was devastating. Men died filling canteens, walking patrol. Americans fired blindly into trees, wasting thousands of rounds. The expert solution—more machine guns, more mortars—was useless. The battalion commander realized he was losing men to an enemy he couldn’t see. He didn’t need more firepower. He needed a surgeon.

The Test

Desperate, the commander summoned George. Could the mail-order rifle actually hit anything? George calmly listed his credentials: Illinois state championship at 1,000 yards, youngest winner, five rounds inside a 4-inch circle at 300 yards, six-inch groups at 600 yards. He wasn’t bragging—he was stating facts.

He spent the night preparing for a suicide mission. He cleaned the Winchester, checked the scope, loaded standard .30-06 ball ammo. At dawn, he moved into the bunker, scanning the groves. He didn’t look for men—he looked for things that didn’t belong.

At 9:17, he saw it: a branch moved with no wind. 87 feet up, a man in dark clothing, waiting to kill. George adjusted his scope, breathed out, squeezed the trigger. The rifle kicked. The sniper tumbled 90 feet to the jungle floor. George worked the bolt, reloaded, and waited. He knew snipers worked in pairs. Twenty-six minutes later, he found the spotter, climbing down. George fired. Two shots, two kills.

By noon, George had killed five snipers. The men who mocked his “toy” stopped laughing. The Japanese adapted, stopped moving during the day. The duel was on.

The Duel

On January 23, rain reduced visibility. George waited. At 9:12, he spotted a sniper 290 yards out—testing his range. George dropped him. The Japanese responded with mortars, triangulating his position. George barely escaped as his bunker was destroyed. He relocated and killed two more snipers.

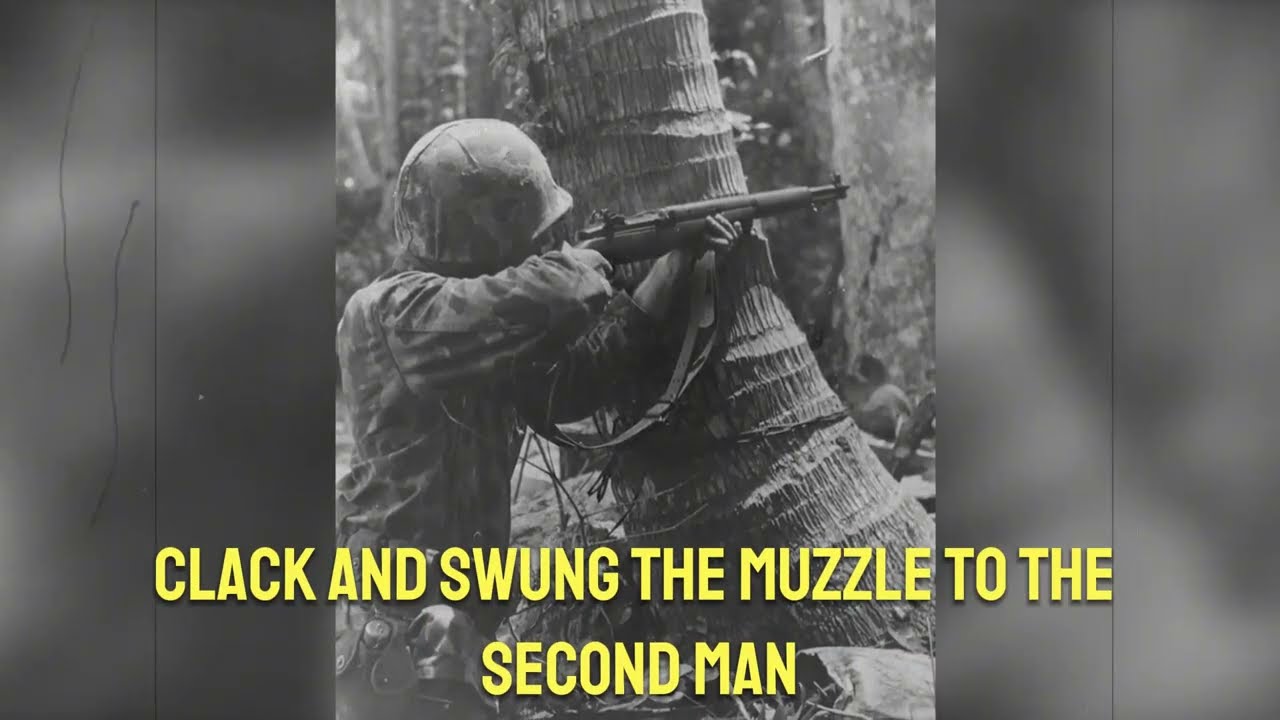

On January 24, the rain returned. George moved to new cover. He spotted a sniper in a palm tree—too obvious. It was bait. He ignored it, found the real sniper 91 feet up in a banyan, perfectly concealed. George shot the bait, then the real sniper as he reacted. He relocated, dodged machine gun fire, and killed two more snipers working as a hunter-killer team on the ground.

When an infantry patrol arrived to check the bodies, George realized he’d left bootprints right to his hiding spot. He was discovered in a crater, water up to his chin, holding the Winchester vertically to keep water out of the barrel. The first soldier saw him—George fired from the hip. Two more appeared—he dropped them. Five rounds left, six men coming. George broke contact, ran, bullets snapping past his ears. He dove into another crater, waited for his heart to slow, checked the rifle—one round left.

He moved carefully, circled back toward American lines, and returned to headquarters. Four days, 11 snipers dead, three more infantry killed. The battalion had been paralyzed; now, the sector was clear.

The Legacy

George cleaned the Winchester, then was summoned by regimental command. Instead of a reprimand, he was asked to teach others. Fourteen Springfield sniper rifles, 40 expert marksmen. George built a sniper section, organized them into two-man teams, trained them to hunt, not just shoot.

On February 1, the final exam: real combat. George’s team killed six men with seven shots; the section killed 23 Japanese with zero American casualties. The officers who mocked the “toy” now begged for sniper teams to cover their patrols.

On February 7, George was wounded by a Japanese rifleman. He was evacuated, but his section had achieved 74 confirmed kills in 12 days, with zero friendly losses. The Winchester Model 70 had proven that precision could beat firepower in the right terrain.

George recovered, volunteered for Merrill’s Marauders in Burma, modified his rifle, and continued the legacy. After the war, he became a diplomat and wrote Shots Fired in Anger, a technical analysis of jungle warfare that became a bible for military historians.

He died in 2009 at age 90, having seen sniper tactics institutionalized in the US Army and Marine Corps. His Winchester Model 70 sits in the National Firearms Museum in Virginia—unassuming, surrounded by famous weapons. It looks like a deer rifle, but it is the physical evidence of one man’s refusal to accept the status quo. It is the “toy” that cleared a ridge when a thousand men couldn’t.

Why This Story Matters

History is written about generals and maps, but battles are decided by individuals—by men like John George, who faced an impossible problem and solved it himself. He ignored laughter, took what he had, and went into the darkness alone.

We tell this story so John George doesn’t disappear into silence. If you felt the tension of that water-filled crater and the recoil of that Winchester, remember: the obscure, the forgotten, and the brave matter. The “toy” rifle was no toy—it was the proof that sometimes, one man and one idea can change the outcome of a war.