A British Officer Found a German POW Nurse Tied to a Post — The Sign Said ‘Traitor

Rhineland, Germany. April 1945. The village square was a haunting sight, filled with the acrid smell of ash and rotting plaster. Smoke curled from the roofless walls of buildings that had once been homes, now reduced to mere memories of a life before the war. Lieutenant James Avery stepped through the rubble, his Lee-Enfield rifle slung low, boots crunching over shards of glass that had once been a baker’s window.

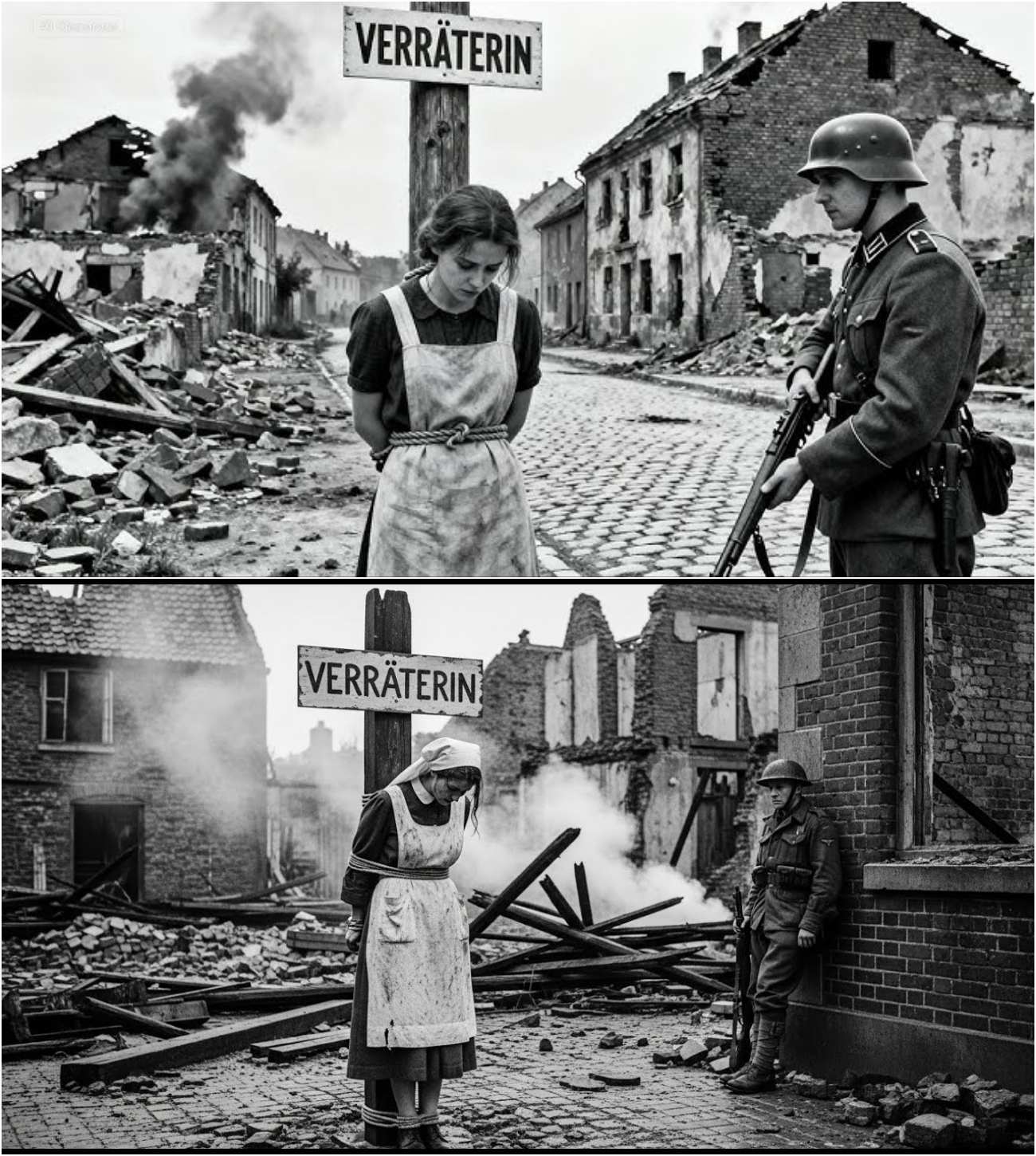

But then he saw her—a woman in a nurse’s uniform, torn at the shoulder, mud-streaked and bloodied, tied to a wooden post in the center of the square. Above her head, a hand-painted sign in brutal block letters read “Veratin, traitor.” A small crowd of villagers surrounded her, their faces twisted with anger and grief. Old men in threadbare coats, women with hollow cheeks, and a child kicking gravel. Someone spat on the ground, the sound landing wet against the stone.

Avery felt the weight of the moment pressing down on him. He had only 60 seconds before someone in that crowd decided that waiting was worse than guilt. He was not supposed to be here; his section had been tasked with securing the eastern checkpoint, clearing the roads, marking the mines, letting the village sort itself out. But a woman’s cry had pulled him in—sharp, sudden, cut short by a hand or a fist.

“Corporal Doors,” he motioned, “hold position. Safety’s on. No shots.” He stepped into the square alone, feeling the eyes of the crowd turn toward him.

An old man in a stained coat stepped forward, gesturing at the woman as if she were evidence, proof of betrayal. “She helped your men. She gave them water while our boys bled. She is a traitor!” Avery’s heartbeat pounded in his throat. He had stood in burning houses and felt calmer. This was different. This was a village trying to cauterize its shame by burning the wound.

He looked at the woman. Her wrists were raw where the rope bit into her skin. Her face was bruised, violet and gray. But when her eyes lifted to meet his, they were not pleading; they were exhausted, resigned. What happened next would test the thinnest line in war—the one between justice and murder, between orders and conscience, between the man he was taught to be and the man war demanded he become.

Avery did not raise his rifle. Instead, he planted it into the cobblestones like a stake claiming ground. “Halt,” he commanded in clipped German. The crowd hesitated, not from fear, but from the sudden friction of interrupted momentum. They were a river, now pooling, uncertain which way to flow.

The old man recovered first, his voice climbing in indignation. “This does not concern you, hair off its ear. This is German justice. Our village, our traitor.”

“Your village is now under British jurisdiction,” Avery replied, his German stiff but deliberate, each word placed like a chess piece. “And I see no justice here, only a rope and a crowd.”

A younger man pushed forward, gaunt-faced with one sleeve pinned empty at the shoulder—a veteran, the kind who carried war in his bones and rage in his marrow. “She gave water to your men,” he spat, jabbing his remaining hand toward the woman. “While my brother died three streets away, choking on his own blood, she was washing British wounds, bandaging British hands. She chose them over us!”

Avery let the silence sit, counting three breaths before he spoke again. “What is her name?”

The question landed like a wrench in gears. “What?” the one-armed man blinked.

“The one you are executing for treason,” Avery repeated, slower now. “You must know her name, her rank, her unit, the specific charges. Show me the court martial documentation. Show me the official order. Show me anything that says this is law and not a lynching.”

The old man sputtered, “We do not need papers to know betrayal.”

“Then you do not have justice. You have revenge,” Avery’s voice hardened, a blade finding its edge. “And revenge is not yours to take. Not anymore.”

A woman’s voice rose from the back, ragged with grief. “She let them live! The soldiers who bombed our children, who burned our homes. She saved them!”

Avery turned toward the voice, finding a mother or a widow, someone hollowed out by loss and looking for a shape to fill the void. “Did she pull the triggers? Did she load the bombers? Did she give the orders?”

“She gave them mercy!” the woman choked out. “While we had none!”

“Then she was a nurse,” Avery said simply, “doing what nurses do.”

“Veratin!” someone shouted from the crowd’s edge. “Traitor!” The word landed like a stone thrown into a pond. Others picked it up, a half-hearted chant gaining heat, the mob trying to remember why it had gathered, trying to reconvince itself.

Avery saw it then—the ringleader, not the old man, not the veteran. A younger man, late 20s, standing three rows back. He wore an expensive coat despite the ruin, clean-shaven with cold, calculating eyes. This man didn’t lose family; he lost standing, lost something the war took from him, and he needed someone to pay.

“Hair off,” the ringleader said smoothly, stepping forward with a politician’s ease. “We understand your position, but you must understand ours. This woman defied orders. She stayed behind when we were told to evacuate. She aided enemy combatants. These are facts. The sentence has been decided.”

“Decided by whom?” Avery asked, meeting the man’s gaze directly.

“By the people she betrayed.”

“Then the people have no authority.”

Avery’s words dropped like a gavel. “I do.”

The ringleader’s smile faltered. Avery pivoted, addressing the crowd now, his voice carrying. “This woman is under British protective custody. Any attempt to harm her will be considered an act of aggression against Allied forces and will be met accordingly. If you have charges, you will submit them in writing to military government. If you have evidence, you will present it to a proper tribunal. Until then, she is not yours.”

The old man tried once more, his voice shaking. “But she—”

“I know what she did,” Avery interrupted, though he didn’t. Not yet. “And I know what you want to do. But wanting is not the same as being right. And being angry is not the same as being just.”

He turned to the post. The woman’s eyes tracked him, exhausted, weary, waiting for the next cruelty. “Froline,” he said, voice low enough that only she heard. “I am Lieutenant Avery, British Army. I’m going to cut the rope now. Do you understand?”

She nodded, barely—a movement small as a prayer. Avery drew his knife, the blade catching the gray light. The rope was cheap hemp, frayed at the edges, tied with the kind of knot you learn for tethering animals. It parted under pressure, falling away like a spell breaking. The woman collapsed forward, and Avery caught her, his arm around her shoulders, steadying her weight against his chest. She weighed almost nothing; war had rationed even the substance of bodies.

“It’s over,” he murmured. Her breath shuddered against his uniform. Behind him, the crowd did not cheer or riot; it simply dispersed slowly, reluctantly, like smoke losing its shape. The ringleader melted back into the rubble, the old man spat once more and turned away, and the mother with the ragged voice covered her face and wept.

“Corporal Doors,” Avery said, “the ambulance is two minutes out.”

“Good.” Avery shifted his grip, lifting the woman fully, cradling her like something breakable, which she was, which they all were. As he carried her across the square toward the waiting section, he felt it—the cost of choosing. His hands were steady. His orders were clear. But something inside him had shifted, a weight redistributed. The war was never impersonal, but it had been distant—a thing of maps and objectives, movements and missions. Now it was this: a woman’s pulse against his forearm, a village’s hatred in his wake, a choice made not because it was ordered, but because it was necessary.

When the ambulance arrived, olive drab with the Red Cross painted bright on the canvas, he handed her over to the medics with the careful precision of someone passing a lit candle in the dark. “Take her to the aid station,” he told the driver. “Protective custody. No visitors without my clearance.” The driver nodded, professional. “Understood, sir.”

Avery stepped back, watching the ambulance pull away, tires grinding gravel and ash. The square was empty now, except for his section. The post stood alone, the sign still nailed above it: “Veratin.” Doors cleared his throat. “Orders, sir?”

Avery looked at the post for a long moment. Then he reached up, wrenched the sign free with both hands. The wood splintered, the nails shrieked. He dropped it to the ground, letting it lie there face down in the mud. “We move out in ten,” he said. “Check the perimeter. Mark this square secure.”

“And the woman, sir?”

Avery turned, looking at his corporal. Doors had been with him since Normandy, seen every kind of hell, never asked a question that wasn’t necessary. “The woman,” Avery said slowly, “is no longer their problem. She’s ours.”

The field hospital tent smelled of canvas, iodine, and the particular staleness of air that had cycled through too many lungs. Avery sat on an overturned crate beside the cot, watching the woman sleep. She had been unconscious for four hours. The medic, a Scotsman named Mcloud with hands like a watchmaker, had cataloged her injuries with clinical precision: two cracked ribs, severe dehydration, contusions mapping her back like a failed geography lesson, rope burns encircling both wrists.

She would wake, Mcloud said; bodies just demand the rest it’s owed. Now, as dusk bled through the tent canvas, she stirred. Her eyes opened slowly, focusing on nothing, then everything. She saw the IV line first, then the British field dressing on her shoulder, then Avery. She didn’t flinch; she just watched him with the careful neutrality of someone who had learned not to expect kindness.

“Wasser,” she whispered.

Avery reached for the canteen Mcloud left, holding it to her lips. She drank like someone who had forgotten the shape of mercy—small sips, hesitant, as if the water might be rescinded. “Thank you,” she said in German, then switched to heavily accented English. “You are the officer from the square.”

He set the canteen down. “You’re safe here, under British protection.”

She almost laughed, the sound catching in her throat and becoming a cough. “Safe? Yes, I have heard this word before.”

“What’s your name?” Avery asked.

A pause, as if even this simple fact might be dangerous. “Leisa,” she said finally. “Liza Hartman. I was a nurse. Criggs Lazarette, Sector West Rhineland front.”

“Was?” he asked.

“I think,” she said quietly, “I am not a nurse anymore, only a traitor.”

Avery leaned forward. “Tell me what happened from the beginning.”

She told it slowly in fragments, like someone assembling a broken mirror. The hospital was a repurposed schoolhouse, she said—20 beds that became 40, then 60, then bodies on the floor because there was nowhere else to put them. Three doctors, eight nurses, dwindling supplies that turned medicine into mathematics. Who gets the morphine? Who gets the bandage? Who gets to die slower?

“February was when it started to collapse,” Liza said, her voice flat with exhaustion. “The front didn’t retreat. It dissolved. One day we had supply lines; the next we had rumors. German units mixed with stragglers, deserters, boys in uniforms three sizes too large who looked at the nurses like they were ghosts.”

The order came in March, Liza said, her eyes finding his. “Evacuate. Fall back. Leave the ones who cannot walk.” Avery knew this order; he had read the intelligence reports. The Wehrmacht was in full collapse, discipline fraying, officers executing their own men for refusing suicidal stands.

“We were supposed to leave them,” she continued. “32 men, some German, some not. We had British prisoners, Americans, even a Russian. All bleeding the same, all needing hands that knew how to close wounds instead of opening them.”

She stayed. Three nurses stayed. The doctors fled. “We boiled bandages in rainwater,” she said. “Used schnaps when the ether ran out. I held a boy’s hand while he died. A German boy, maybe 17. He called me Mutti—mother. I was 23.”

The detail landed like shrapnel, the stink of infection, the sound of shattered morphine vials swept into corners. The way gangrene smells like earth and rot together. She described amputations by candlelight, a British sergeant who sang hymns through his fever, a Luftwaffe pilot who sketched birds on the walls with charcoal from the stove.

“Then your men came,” she said. “A patrol, lost, looking for their unit. One was wounded. Shrapnel in his shoulder, bleeding badly, red hair, freckles like a child. Avery listened, did not interrupt, let her build the testimony brick by brick.”

His name was Thomas—Tommy. “He made jokes even while I dug metal from his flesh. Asked if I had a sister. I told him I had three brothers, all dead now. He cried—not from pain, from that.”

The British patrol stayed two days, long enough for Tommy’s fever to break, long enough for the other wounded to see that the enemy wore the same exhaustion they did. “One of your soldiers, an older man, a corporal—he shared his chocolate. Real chocolate. I had not tasted it in two years. He gave it to the German boys too. Said, ‘War’s done, lads. Might as well be human before we go back to killing each other.’”

When the patrol left, they offered to take her. She refused. “Someone had to stay.” But someone saw a villager—a failed Wehrmacht officer, or someone claiming to be one in a war where authority was whatever uniform you could scavenge. He called it treason, Liza said, her voice hardening. “Aiding the enemy, consorting with occupiers, betraying the Reich.”

The real betrayal, Avery thought, was expecting her to choose nation over mercy. “They came at night,” she continued, “dragged me from the hospital. The wounded, those who could still move, tried to stop it. A boy with one leg stood between me and the soldiers. They beat him unconscious.”

She was tied to the post at dawn, the sign painted while she watched. “They told me I would hang at sunset as an example so others would know the price of kindness.” Her voice fractured on the last word. She turned her face away toward the tent wall, where shadows flickered like the ghosts of flames.

Avery sat in the silence that followed. Outside, the camp settled into evening routine: mess tins clanging, voices trading cigarettes and rumors, the distant cough of an engine. He thought about the war they teach at Sandhurst—the clean one with clear enemies and clearer orders. Then he thought about the war he had lived—the one where a German nurse saving a British soldier becomes a capital crime.

“In the last months,” he said quietly, speaking as much to himself as to her, “we have seen things fall apart—not just armies. People. The rules we thought were iron turned out to be smoke.”

He had seen reprisal killings, civilians shot for hiding deserters, soldiers hanged for refusing to defend ruins—a world where mercy became heresy and survival demanded you choose between your humanity and your life. Liza looked back at him, her eyes dry now, exhaustion having burned through the tears. “What happens to me now?” she asked.

“You stay here,” Avery said. “Under protection. I’ll make sure the record states you acted as a medical professional under impossible conditions. No charges, no trial, no more signs.”

“And when you leave?” It was the question he had been avoiding.

“Then you will have papers that say the British Army vouches for your character.” It may not be enough, but it is what I can give. She nodded slowly, accepting this fragile promise. “Thank you, Lieutenant Avery,” she said. “For the water, for the words, for standing in the square when you did not have to.”

“I did have to,” he replied. “I just didn’t know it until I saw the rope.”

British Second Army Headquarters, Temporary Command Post, Rhineland Sector. April 17, 1945. Major Clifton sat behind a field desk that had seen better wars. Maps curled at the edges, and a cigarette burned forgotten in a tin ashtray. He read Avery’s incident report for the third time, lips pressed thin. “Lieutenant,” he said, his voice gravelly. “Walk me through your decision tree.”

Avery stood at attention, cap under his arm, uniform still carrying yesterday’s mud. “Sir, I encountered a civilian detained without proper authority. I assessed the situation as extrajudicial punishment and intervened per Article 27 of the Geneva Convention.”

“I know the bloody convention,” Clifton interrupted. “What I don’t know is why you thought it was your job to play magistrate in a German village square.”

With respect, sir, I was preventing a murder.”

“You were exceeding your authority,” Clifton leaned back, the chair groaning. “Your orders were checkpoint security, not social work. Not playing savior to every sob story in a nurse’s uniform.”

The words landed like a slap. Avery kept his face neutral, parade ground blank. “She wasn’t a sob story, sir. She was a prisoner about to be executed by a mob.”

“A German prisoner in a German village dealing with German justice—or injustice, if you prefer. Not your problem.”

Silence filled the space between them, heavy as smoke. Clifton’s size suddenly seemed older. “Listen, James, I understand the impulse. God knows I do. But we’re not here to referee every score they want to settle. We’re here to secure ground, establish order, and move east. The minute you start caring about every rope and post, you stop being a soldier and start being what, sir? A liability.”

The word sat between them like unexploded ordinance. “Permission to speak freely, sir?”

Clifton waved a hand. “You’re already waste deep. Might as well wade in.”

“If we ignore civilians being murdered in our jurisdiction, we’re not establishing order. We’re sanctioning chaos. We become complicit in the very barbarism we’re supposed to be ending.”

“Careful, Lieutenant. That sounds dangerously close to philosophy.”

“We don’t pay you to philosophize. We pay you to follow orders.”

“My orders,” Avery said quietly, “include upholding the laws of war, even when it’s inconvenient.”

Clifton studied him for a long moment, then reached for his cigarette, finding it cold, lighting another. “You know what your problem is, Avery? You still think war has rules.”

From Lieutenant James Avery’s personal diary, April 17, 1945. Mother would say I’m making things complicated again. She always said I thought too much. That thinking was a luxury soldiers couldn’t afford. Maybe she was right. But I keep seeing the rope, the sign, the woman’s face when I cut her free. The way she folded like something held together by will alone.

Clifton asked me why I intervened. I gave him the official answer: Geneva Convention, proper authority, legal duty. But the truth is simpler and more damning. I intervened because if I hadn’t, I would have become the kind of man who walks past a lynching. I would have become the kind of man who lets convenience murder conscience.

The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may not forgive her for being kind.”

“So you saved her for what? Six months? A year?”

“I saved her for one day,” Avery says. “The day she was about to die. That’s all any of us can do.”

Clifton nods slowly. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“Maybe,” Avery echoes. “Or maybe it’s just what we tell ourselves so we can sleep.”

The British DP processing center, Rhineland. The paperwork takes longer than the rescue. Liza Hartman sits across from a clerk who types with two fingers, hunting and pecking through her testimony. Name, age, occupation, circumstances of detention, reason for British intervention. The clerk asks if she has family. She says no. He asks if she has a destination. She says no.

He stamps three forms, files them in a folder that joins hundreds of others in a canvas bag destined for an archive that may never be opened. Next, the clerk calls. Liza stands holding a paper that says she is a displaced person under Allied protection. It does not say she is innocent. It does not say she was right. It says only that she exists and that for now, that is enough.

Avery watches from the doorway. She sees him, nods once—acknowledgment, not gratitude. Gratitude implies debt. What passed between them in that square was something else—something without a name in any language he knows.

“Where will you go?” he asks.

“West,” she says, “away from the ruins. Perhaps to family I hope still breathe. Perhaps to no one. It does not matter. I am alive, which means I must continue being alive.”

“If you need anything—”

“You have given what you could, Lieutenant. The rest is mine to carry.”

She walks away, folding herself into the river of refugees that flows west like water finding its level. Avery watches until she disappears into the crowd—another story the war will swallow and never fully digest. He wonders if he will remember her face in 10 years, 20, or if she will become just another moment in a war built of moments—important when it happened, inevitable when it’s over.

Avery returns to the square before his unit moves out. Dawnlight cuts through the ruins, painting everything the color of old bone. The post still stands, though someone has tried to burn it. The wood is charred at the base, black tongue marks licking upward, but it did not fall. It remains, defiant or indifferent; it’s hard to say. The sign lies face down in the mud where he dropped it. Rain has softened the letters, “Veratin,” the paint bleeding into the grain, the accusation dissolving into abstraction.

Avery kneels, turns it over, and stares at the word that meant death, now just wood and weather. He thinks about burning it, about smashing it, about carrying it back to headquarters as evidence of something, though evidence of what he cannot name. Instead, he leaves it there, half-buried, fading. Some things should be remembered. Some things should be forgotten. Most things exist in the terrible space between.

In the final months of World War II, Europe dissolved into chaos that history textbooks struggle to capture. The liberation was not clean; it was not simple. It was a reckoning that came in waves, each one exposing new layers of guilt, new categories of victim, new impossible questions about who deserved mercy and who deserved judgment.

Between April and August 1945, Allied forces documented over 10,000 cases of reprisal killings across occupied Germany—civilians accused of collaboration, deserters executed by their own retreating armies, women punished for loving the wrong uniform. The numbers are estimates; most deaths left no paperwork, no witness, no grave. Military hospitals and field stations became sanctuaries for those caught between vengeance and law.

Nurses like Liza Hartman—German, French, Dutch, Italian—who treated the wounded regardless of flag found themselves branded traitors by communities desperate to assign blame for their suffering. The International Red Cross recorded 847 such cases in Germany alone. Most received no recognition; some received punishment. A handful, like Liza, received the one thing rarer than mercy in those days: a second chance.

Lieutenant James Avery was one of thousands of Allied officers tasked with policing the collapse. They cleared mines, secured roads, and made impossible decisions about when to intervene in the rage of villages that had earned their rage honestly. Some looked away; some drew lines. All of them carried the weight of choices made in moments too fast for certainty, too important for doubt.

Avery writes to his mother from a requisitioned house in what used to be a German officer’s quarters. The furniture is gone, looted or burned. Only the wallpaper remains, floral patterns faded by sun and smoke. “Dear Mother, I cannot tell you much about where I am or what I do. The censors would cut my words to confetti. But I can tell you this: the war you read about in newspapers is not the war we live. The war you read about has clear sides. The one we live has only shades of gray, each one darker than the last.”

He thinks of David, his brother who died at Dunkirk, shot while covering a retreat that saved 30 men. A posthumous commendation, a medal sent to their mother in a box she never opened. David believed in duty above all—duty above doubt, above fear, above the small voice that asks why. Avery enlisted three months later, trying to fill the space his brother left, trying to be the kind of soldier David was—certain, unwavering, faithful to orders as if orders were gospel.

But war teaches you things training doesn’t. It teaches you that orders come from men, and men are fallible. It teaches you that duty can be a suicide pact if you’re not careful. It teaches you that sometimes the most important thing you can do is say no. David never learned that. David died believing.

Avery is still trying to figure out what he believes in. The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may not forgive her for being kind.”

“So you saved her for what? Six months? A year?”

“I saved her for one day,” Avery says. “The day she was about to die. That’s all any of us can do.”

Clifton nods slowly. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“Maybe,” Avery echoes. “Or maybe it’s just what we tell ourselves so we can sleep.”

The British DP processing center, Rhineland. The paperwork takes longer than the rescue. Liza Hartman sits across from a clerk who types with two fingers, hunting and pecking through her testimony. Name, age, occupation, circumstances of detention, reason for British intervention. The clerk asks if she has family. She says no. He asks if she has a destination. She says no.

He stamps three forms, files them in a folder that joins hundreds of others in a canvas bag destined for an archive that may never be opened. Next, the clerk calls. Liza stands holding a paper that says she is a displaced person under Allied protection. It does not say she is innocent. It does not say she was right. It says only that she exists and that for now, that is enough.

Avery watches from the doorway. She sees him, nods once—acknowledgment, not gratitude. Gratitude implies debt. What passed between them in that square was something else—something without a name in any language he knows.

“Where will you go?” he asks.

“West,” she says, “away from the ruins. Perhaps to family I hope still breathe. Perhaps to no one. It does not matter. I am alive, which means I must continue being alive.”

“If you need anything—”

“You have given what you could, Lieutenant. The rest is mine to carry.”

She walks away, folding herself into the river of refugees that flows west like water finding its level. Avery watches until she disappears into the crowd—another story the war will swallow and never fully digest. He wonders if he will remember her face in 10 years, 20, or if she will become just another moment in a war built of moments—important when it happened, inevitable when it’s over.

Avery returns to the square before his unit moves out. Dawnlight cuts through the ruins, painting everything the color of old bone. The post still stands, though someone has tried to burn it. The wood is charred at the base, black tongue marks licking upward, but it did not fall. It remains, defiant or indifferent; it’s hard to say. The sign lies face down in the mud where he dropped it. Rain has softened the letters, “Veratin,” the paint bleeding into the grain, the accusation dissolving into abstraction.

Avery kneels, turns it over, and stares at the word that meant death, now just wood and weather. He thinks about burning it, about smashing it, about carrying it back to headquarters as evidence of something, though evidence of what he cannot name. Instead, he leaves it there, half-buried, fading. Some things should be remembered. Some things should be forgotten. Most things exist in the terrible space between.

In the final months of World War II, Europe dissolved into chaos that history textbooks struggle to capture. The liberation was not clean; it was not simple. It was a reckoning that came in waves, each one exposing new layers of guilt, new categories of victim, new impossible questions about who deserved mercy and who deserved judgment.

Between April and August 1945, Allied forces documented over 10,000 cases of reprisal killings across occupied Germany—civilians accused of collaboration, deserters executed by their own retreating armies, women punished for loving the wrong uniform. The numbers are estimates; most deaths left no paperwork, no witness, no grave. Military hospitals and field stations became sanctuaries for those caught between vengeance and law.

Nurses like Liza Hartman—German, French, Dutch, Italian—who treated the wounded regardless of flag found themselves branded traitors by communities desperate to assign blame for their suffering. The International Red Cross recorded 847 such cases in Germany alone. Most received no recognition; some received punishment. A handful, like Liza, received the one thing rarer than mercy in those days: a second chance.

Lieutenant James Avery was one of thousands of Allied officers tasked with policing the collapse. They cleared mines, secured roads, and made impossible decisions about when to intervene in the rage of villages that had earned their rage honestly. Some looked away; some drew lines. All of them carried the weight of choices made in moments too fast for certainty, too important for doubt.

Avery writes to his mother from a requisitioned house in what used to be a German officer’s quarters. The furniture is gone, looted or burned. Only the wallpaper remains, floral patterns faded by sun and smoke. “Dear Mother, I cannot tell you much about where I am or what I do. The censors would cut my words to confetti. But I can tell you this: the war you read about in newspapers is not the war we live. The war you read about has clear sides. The one we live has only shades of gray, each one darker than the last.”

He thinks of David, his brother who died at Dunkirk, shot while covering a retreat that saved 30 men. A posthumous commendation, a medal sent to their mother in a box she never opened. David believed in duty above all—duty above doubt, above fear, above the small voice that asks why. Avery enlisted three months later, trying to fill the space his brother left, trying to be the kind of soldier David was—certain, unwavering, faithful to orders as if orders were gospel.

But war teaches you things training doesn’t. It teaches you that orders come from men, and men are fallible. It teaches you that duty can be a suicide pact if you’re not careful. It teaches you that sometimes the most important thing you can do is say no. David never learned that. David died believing.

Avery is still trying to figure out what he believes in. The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may not forgive her for being kind.”

“So you saved her for what? Six months? A year?”

“I saved her for one day,” Avery says. “The day she was about to die. That’s all any of us can do.”

Clifton nods slowly. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“Maybe,” Avery echoes. “Or maybe it’s just what we tell ourselves so we can sleep.”

The British DP processing center, Rhineland. The paperwork takes longer than the rescue. Liza Hartman sits across from a clerk who types with two fingers, hunting and pecking through her testimony. Name, age, occupation, circumstances of detention, reason for British intervention. The clerk asks if she has family. She says no. He asks if she has a destination. She says no.

He stamps three forms, files them in a folder that joins hundreds of others in a canvas bag destined for an archive that may never be opened. Next, the clerk calls. Liza stands holding a paper that says she is a displaced person under Allied protection. It does not say she is innocent. It does not say she was right. It says only that she exists and that for now, that is enough.

Avery watches from the doorway. She sees him, nods once—acknowledgment, not gratitude. Gratitude implies debt. What passed between them in that square was something else—something without a name in any language he knows.

“Where will you go?” he asks.

“West,” she says, “away from the ruins. Perhaps to family I hope still breathe. Perhaps to no one. It does not matter. I am alive, which means I must continue being alive.”

“If you need anything—”

“You have given what you could, Lieutenant. The rest is mine to carry.”

She walks away, folding herself into the river of refugees that flows west like water finding its level. Avery watches until she disappears into the crowd—another story the war will swallow and never fully digest. He wonders if he will remember her face in 10 years, 20, or if she will become just another moment in a war built of moments—important when it happened, inevitable when it’s over.

Avery returns to the square before his unit moves out. Dawnlight cuts through the ruins, painting everything the color of old bone. The post still stands, though someone has tried to burn it. The wood is charred at the base, black tongue marks licking upward, but it did not fall. It remains, defiant or indifferent; it’s hard to say. The sign lies face down in the mud where he dropped it. Rain has softened the letters, “Veratin,” the paint bleeding into the grain, the accusation dissolving into abstraction.

Avery kneels, turns it over, and stares at the word that meant death, now just wood and weather. He thinks about burning it, about smashing it, about carrying it back to headquarters as evidence of something, though evidence of what he cannot name. Instead, he leaves it there, half-buried, fading. Some things should be remembered. Some things should be forgotten. Most things exist in the terrible space between.

In the final months of World War II, Europe dissolved into chaos that history textbooks struggle to capture. The liberation was not clean; it was not simple. It was a reckoning that came in waves, each one exposing new layers of guilt, new categories of victim, new impossible questions about who deserved mercy and who deserved judgment.

Between April and August 1945, Allied forces documented over 10,000 cases of reprisal killings across occupied Germany—civilians accused of collaboration, deserters executed by their own retreating armies, women punished for loving the wrong uniform. The numbers are estimates; most deaths left no paperwork, no witness, no grave. Military hospitals and field stations became sanctuaries for those caught between vengeance and law.

Nurses like Liza Hartman—German, French, Dutch, Italian—who treated the wounded regardless of flag found themselves branded traitors by communities desperate to assign blame for their suffering. The International Red Cross recorded 847 such cases in Germany alone. Most received no recognition; some received punishment. A handful, like Liza, received the one thing rarer than mercy in those days: a second chance.

Lieutenant James Avery was one of thousands of Allied officers tasked with policing the collapse. They cleared mines, secured roads, and made impossible decisions about when to intervene in the rage of villages that had earned their rage honestly. Some looked away; some drew lines. All of them carried the weight of choices made in moments too fast for certainty, too important for doubt.

Avery writes to his mother from a requisitioned house in what used to be a German officer’s quarters. The furniture is gone, looted or burned. Only the wallpaper remains, floral patterns faded by sun and smoke. “Dear Mother, I cannot tell you much about where I am or what I do. The censors would cut my words to confetti. But I can tell you this: the war you read about in newspapers is not the war we live. The war you read about has clear sides. The one we live has only shades of gray, each one darker than the last.”

He thinks of David, his brother who died at Dunkirk, shot while covering a retreat that saved 30 men. A posthumous commendation, a medal sent to their mother in a box she never opened. David believed in duty above all—duty above doubt, above fear, above the small voice that asks why. Avery enlisted three months later, trying to fill the space his brother left, trying to be the kind of soldier David was—certain, unwavering, faithful to orders as if orders were gospel.

But war teaches you things training doesn’t. It teaches you that orders come from men, and men are fallible. It teaches you that duty can be a suicide pact if you’re not careful. It teaches you that sometimes the most important thing you can do is say no. David never learned that. David died believing.

Avery is still trying to figure out what he believes in. The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may not forgive her for being kind.”

“So you saved her for what? Six months? A year?”

“I saved her for one day,” Avery says. “The day she was about to die. That’s all any of us can do.”

Clifton nods slowly. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“Maybe,” Avery echoes. “Or maybe it’s just what we tell ourselves so we can sleep.”

The British DP processing center, Rhineland. The paperwork takes longer than the rescue. Liza Hartman sits across from a clerk who types with two fingers, hunting and pecking through her testimony. Name, age, occupation, circumstances of detention, reason for British intervention. The clerk asks if she has family. She says no. He asks if she has a destination. She says no.

He stamps three forms, files them in a folder that joins hundreds of others in a canvas bag destined for an archive that may never be opened. Next, the clerk calls. Liza stands holding a paper that says she is a displaced person under Allied protection. It does not say she is innocent. It does not say she was right. It says only that she exists and that for now, that is enough.

Avery watches from the doorway. She sees him, nods once—acknowledgment, not gratitude. Gratitude implies debt. What passed between them in that square was something else—something without a name in any language he knows.

“Where will you go?” he asks.

“West,” she says, “away from the ruins. Perhaps to family I hope still breathe. Perhaps to no one. It does not matter. I am alive, which means I must continue being alive.”

“If you need anything—”

“You have given what you could, Lieutenant. The rest is mine to carry.”

She walks away, folding herself into the river of refugees that flows west like water finding its level. Avery watches until she disappears into the crowd—another story the war will swallow and never fully digest. He wonders if he will remember her face in 10 years, 20, or if she will become just another moment in a war built of moments—important when it happened, inevitable when it’s over.

Avery returns to the square before his unit moves out. Dawnlight cuts through the ruins, painting everything the color of old bone. The post still stands, though someone has tried to burn it. The wood is charred at the base, black tongue marks licking upward, but it did not fall. It remains, defiant or indifferent; it’s hard to say. The sign lies face down in the mud where he dropped it. Rain has softened the letters, “Veratin,” the paint bleeding into the grain, the accusation dissolving into abstraction.

Avery kneels, turns it over, and stares at the word that meant death, now just wood and weather. He thinks about burning it, about smashing it, about carrying it back to headquarters as evidence of something, though evidence of what he cannot name. Instead, he leaves it there, half-buried, fading. Some things should be remembered. Some things should be forgotten. Most things exist in the terrible space between.

In the final months of World War II, Europe dissolved into chaos that history textbooks struggle to capture. The liberation was not clean; it was not simple. It was a reckoning that came in waves, each one exposing new layers of guilt, new categories of victim, new impossible questions about who deserved mercy and who deserved judgment.

Between April and August 1945, Allied forces documented over 10,000 cases of reprisal killings across occupied Germany—civilians accused of collaboration, deserters executed by their own retreating armies, women punished for loving the wrong uniform. The numbers are estimates; most deaths left no paperwork, no witness, no grave. Military hospitals and field stations became sanctuaries for those caught between vengeance and law.

Nurses like Liza Hartman—German, French, Dutch, Italian—who treated the wounded regardless of flag found themselves branded traitors by communities desperate to assign blame for their suffering. The International Red Cross recorded 847 such cases in Germany alone. Most received no recognition; some received punishment. A handful, like Liza, received the one thing rarer than mercy in those days: a second chance.

Lieutenant James Avery was one of thousands of Allied officers tasked with policing the collapse. They cleared mines, secured roads, and made impossible decisions about when to intervene in the rage of villages that had earned their rage honestly. Some looked away; some drew lines. All of them carried the weight of choices made in moments too fast for certainty, too important for doubt.

Avery writes to his mother from a requisitioned house in what used to be a German officer’s quarters. The furniture is gone, looted or burned. Only the wallpaper remains, floral patterns faded by sun and smoke. “Dear Mother, I cannot tell you much about where I am or what I do. The censors would cut my words to confetti. But I can tell you this: the war you read about in newspapers is not the war we live. The war you read about has clear sides. The one we live has only shades of gray, each one darker than the last.”

He thinks of David, his brother who died at Dunkirk, shot while covering a retreat that saved 30 men. A posthumous commendation, a medal sent to their mother in a box she never opened. David believed in duty above all—duty above doubt, above fear, above the small voice that asks why. Avery enlisted three months later, trying to fill the space his brother left, trying to be the kind of soldier David was—certain, unwavering, faithful to orders as if orders were gospel.

But war teaches you things training doesn’t. It teaches you that orders come from men, and men are fallible. It teaches you that duty can be a suicide pact if you’re not careful. It teaches you that sometimes the most important thing you can do is say no. David never learned that. David died believing.

Avery is still trying to figure out what he believes in. The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may not forgive her for being kind.”

“So you saved her for what? Six months? A year?”

“I saved her for one day,” Avery says. “The day she was about to die. That’s all any of us can do.”

Clifton nods slowly. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“Maybe,” Avery echoes. “Or maybe it’s just what we tell ourselves so we can sleep.”

The British DP processing center, Rhineland. The paperwork takes longer than the rescue. Liza Hartman sits across from a clerk who types with two fingers, hunting and pecking through her testimony. Name, age, occupation, circumstances of detention, reason for British intervention. The clerk asks if she has family. She says no. He asks if she has a destination. She says no.

He stamps three forms, files them in a folder that joins hundreds of others in a canvas bag destined for an archive that may never be opened. Next, the clerk calls. Liza stands holding a paper that says she is a displaced person under Allied protection. It does not say she is innocent. It does not say she was right. It says only that she exists and that for now, that is enough.

Avery watches from the doorway. She sees him, nods once—acknowledgment, not gratitude. Gratitude implies debt. What passed between them in that square was something else—something without a name in any language he knows.

“Where will you go?” he asks.

“West,” she says, “away from the ruins. Perhaps to family I hope still breathe. Perhaps to no one. It does not matter. I am alive, which means I must continue being alive.”

“If you need anything—”

“You have given what you could, Lieutenant. The rest is mine to carry.”

She walks away, folding herself into the river of refugees that flows west like water finding its level. Avery watches until she disappears into the crowd—another story the war will swallow and never fully digest. He wonders if he will remember her face in 10 years, 20, or if she will become just another moment in a war built of moments—important when it happened, inevitable when it’s over.

Avery returns to the square before his unit moves out. Dawnlight cuts through the ruins, painting everything the color of old bone. The post still stands, though someone has tried to burn it. The wood is charred at the base, black tongue marks licking upward, but it did not fall. It remains, defiant or indifferent; it’s hard to say. The sign lies face down in the mud where he dropped it. Rain has softened the letters, “Veratin,” the paint bleeding into the grain, the accusation dissolving into abstraction.

Avery kneels, turns it over, and stares at the word that meant death, now just wood and weather. He thinks about burning it, about smashing it, about carrying it back to headquarters as evidence of something, though evidence of what he cannot name. Instead, he leaves it there, half-buried, fading. Some things should be remembered. Some things should be forgotten. Most things exist in the terrible space between.

In the final months of World War II, Europe dissolved into chaos that history textbooks struggle to capture. The liberation was not clean; it was not simple. It was a reckoning that came in waves, each one exposing new layers of guilt, new categories of victim, new impossible questions about who deserved mercy and who deserved judgment.

Between April and August 1945, Allied forces documented over 10,000 cases of reprisal killings across occupied Germany—civilians accused of collaboration, deserters executed by their own retreating armies, women punished for loving the wrong uniform. The numbers are estimates; most deaths left no paperwork, no witness, no grave. Military hospitals and field stations became sanctuaries for those caught between vengeance and law.

Nurses like Liza Hartman—German, French, Dutch, Italian—who treated the wounded regardless of flag found themselves branded traitors by communities desperate to assign blame for their suffering. The International Red Cross recorded 847 such cases in Germany alone. Most received no recognition; some received punishment. A handful, like Liza, received the one thing rarer than mercy in those days: a second chance.

Lieutenant James Avery was one of thousands of Allied officers tasked with policing the collapse. They cleared mines, secured roads, and made impossible decisions about when to intervene in the rage of villages that had earned their rage honestly. Some looked away; some drew lines. All of them carried the weight of choices made in moments too fast for certainty, too important for doubt.

Avery writes to his mother from a requisitioned house in what used to be a German officer’s quarters. The furniture is gone, looted or burned. Only the wallpaper remains, floral patterns faded by sun and smoke. “Dear Mother, I cannot tell you much about where I am or what I do. The censors would cut my words to confetti. But I can tell you this: the war you read about in newspapers is not the war we live. The war you read about has clear sides. The one we live has only shades of gray, each one darker than the last.”

He thinks of David, his brother who died at Dunkirk, shot while covering a retreat that saved 30 men. A posthumous commendation, a medal sent to their mother in a box she never opened. David believed in duty above all—duty above doubt, above fear, above the small voice that asks why. Avery enlisted three months later, trying to fill the space his brother left, trying to be the kind of soldier David was—certain, unwavering, faithful to orders as if orders were gospel.

But war teaches you things training doesn’t. It teaches you that orders come from men, and men are fallible. It teaches you that duty can be a suicide pact if you’re not careful. It teaches you that sometimes the most important thing you can do is say no. David never learned that. David died believing.

Avery is still trying to figure out what he believes in. The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may not forgive her for being kind.”

“So you saved her for what? Six months? A year?”

“I saved her for one day,” Avery says. “The day she was about to die. That’s all any of us can do.”

Clifton nods slowly. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“Maybe,” Avery echoes. “Or maybe it’s just what we tell ourselves so we can sleep.”

The British DP processing center, Rhineland. The paperwork takes longer than the rescue. Liza Hartman sits across from a clerk who types with two fingers, hunting and pecking through her testimony. Name, age, occupation, circumstances of detention, reason for British intervention. The clerk asks if she has family. She says no. He asks if she has a destination. She says no.

He stamps three forms, files them in a folder that joins hundreds of others in a canvas bag destined for an archive that may never be opened. Next, the clerk calls. Liza stands holding a paper that says she is a displaced person under Allied protection. It does not say she is innocent. It does not say she was right. It says only that she exists and that for now, that is enough.

Avery watches from the doorway. She sees him, nods once—acknowledgment, not gratitude. Gratitude implies debt. What passed between them in that square was something else—something without a name in any language he knows.

“Where will you go?” he asks.

“West,” she says, “away from the ruins. Perhaps to family I hope still breathe. Perhaps to no one. It does not matter. I am alive, which means I must continue being alive.”

“If you need anything—”

“You have given what you could, Lieutenant. The rest is mine to carry.”

She walks away, folding herself into the river of refugees that flows west like water finding its level. Avery watches until she disappears into the crowd—another story the war will swallow and never fully digest. He wonders if he will remember her face in 10 years, 20, or if she will become just another moment in a war built of moments—important when it happened, inevitable when it’s over.

Avery returns to the square before his unit moves out. Dawnlight cuts through the ruins, painting everything the color of old bone. The post still stands, though someone has tried to burn it. The wood is charred at the base, black tongue marks licking upward, but it did not fall. It remains, defiant or indifferent; it’s hard to say. The sign lies face down in the mud where he dropped it. Rain has softened the letters, “Veratin,” the paint bleeding into the grain, the accusation dissolving into abstraction.

Avery kneels, turns it over, and stares at the word that meant death, now just wood and weather. He thinks about burning it, about smashing it, about carrying it back to headquarters as evidence of something, though evidence of what he cannot name. Instead, he leaves it there, half-buried, fading. Some things should be remembered. Some things should be forgotten. Most things exist in the terrible space between.

In the final months of World War II, Europe dissolved into chaos that history textbooks struggle to capture. The liberation was not clean; it was not simple. It was a reckoning that came in waves, each one exposing new layers of guilt, new categories of victim, new impossible questions about who deserved mercy and who deserved judgment.

Between April and August 1945, Allied forces documented over 10,000 cases of reprisal killings across occupied Germany—civilians accused of collaboration, deserters executed by their own retreating armies, women punished for loving the wrong uniform. The numbers are estimates; most deaths left no paperwork, no witness, no grave. Military hospitals and field stations became sanctuaries for those caught between vengeance and law.

Nurses like Liza Hartman—German, French, Dutch, Italian—who treated the wounded regardless of flag found themselves branded traitors by communities desperate to assign blame for their suffering. The International Red Cross recorded 847 such cases in Germany alone. Most received no recognition; some received punishment. A handful, like Liza, received the one thing rarer than mercy in those days: a second chance.

Lieutenant James Avery was one of thousands of Allied officers tasked with policing the collapse. They cleared mines, secured roads, and made impossible decisions about when to intervene in the rage of villages that had earned their rage honestly. Some looked away; some drew lines. All of them carried the weight of choices made in moments too fast for certainty, too important for doubt.

Avery writes to his mother from a requisitioned house in what used to be a German officer’s quarters. The furniture is gone, looted or burned. Only the wallpaper remains, floral patterns faded by sun and smoke. “Dear Mother, I cannot tell you much about where I am or what I do. The censors would cut my words to confetti. But I can tell you this: the war you read about in newspapers is not the war we live. The war you read about has clear sides. The one we live has only shades of gray, each one darker than the last.”

He thinks of David, his brother who died at Dunkirk, shot while covering a retreat that saved 30 men. A posthumous commendation, a medal sent to their mother in a box she never opened. David believed in duty above all—duty above doubt, above fear, above the small voice that asks why. Avery enlisted three months later, trying to fill the space his brother left, trying to be the kind of soldier David was—certain, unwavering, faithful to orders as if orders were gospel.

But war teaches you things training doesn’t. It teaches you that orders come from men, and men are fallible. It teaches you that duty can be a suicide pact if you’re not careful. It teaches you that sometimes the most important thing you can do is say no. David never learned that. David died believing.

Avery is still trying to figure out what he believes in. The chaos of post-liberation Europe sprawls beyond the command post like a fever dream. Villages police themselves with rope and rumor. Civilians take revenge on collaborators, real and imagined. Women are shaved, beaten, paraded through streets. Men are shot in ditches for crimes as vague as working with them or as specific as being seen.

The Allies try to impose order, but order is a fiction in a world where the rules dissolved months ago. Military government issues proclamations; villagers ignore them. Soldiers patrol streets; the revenge happens at night. Avery has seen it in the last weeks alone—a French woman stoned for sleeping with a German, a Dutch man hanged for requisitioning food, a Belgian priest beaten for sheltering deserters.

Justice as catharsis, punishment as purge. The soldiers caught between. Do you intervene? Do you let it happen? Do you draw the line? Or do you acknowledge the line is already ashes?

British Second Army HQ. Later that evening, Clifton finds Avery smoking outside the mess tent, watching the sky darken over the shattered landscape. “You’re not in trouble,” the major says without preamble. “Officially, the report will note your actions as within acceptable discretion given fluid circumstances. You’ll get no commendation, but no reprimand either.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m still not sure you were right.”

Clifton lights his own cigarette, exhales slowly. “But I’m not sure you were wrong either, and that bothers me more than I care to admit.” They stand in silence, two men watching the same war from different angles.

“Can I ask you something, sir?”

“If I say no, will it stop you?”

“Did you ever wonder if we’re the traitors?”

Clifton turns, eyebrow raised. “Explain.”

“We swore oaths to fight barbarism, to defend civilization, to uphold certain principles. But how often do we ignore those principles because enforcing them is inconvenient? How often do we look away because looking costs too much?”

“Every day,” Clifton says quietly. “Every single day.”

“Then who are we loyal to, sir? Really?”

The major considers this. Ashes fall from his cigarette like snow. “I think,” he says finally, “we’re loyal to the idea that someday, when this is over, we might still recognize ourselves in the mirror. That’s the best I can offer you, Lieutenant. The rest is just surviving until we get there.” He grinds out his cigarette, turns to leave, then pauses.

“The nurse, Liza, what happens to her?”

“She stays under British protection. I’ve arranged transfer to a DP camp with proper documentation.”

“After that?” Avery shrugs. “After that, she’s a German woman in a Germany that may