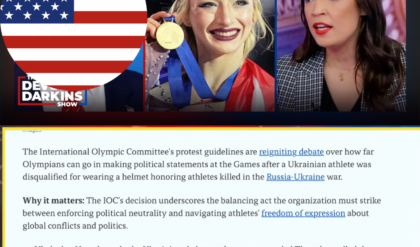

Hiker Vanished in Yosemite — 17 Years Later His Camera Was Found With 47 CHILLING Photos

When park rangers extracted the memory card from that weathered camera in 2020, 17 years after Michael Torres vanished, they expected to find vacation photos. Maybe some shots of the trail, a summit selfie, perhaps the last image showing the moment something went wrong. What they found instead was 47 photographs that would raise more questions than they answered. Because those photos didn’t document an accident. They documented something far more disturbing.

I’ve covered wilderness disappearances for three decades now. I’ve seen accidents, poor judgment, and tragedy in a hundred different forms. But what Michael Torres captured in those final 16 hours on Half Dome Summit was something else entirely.

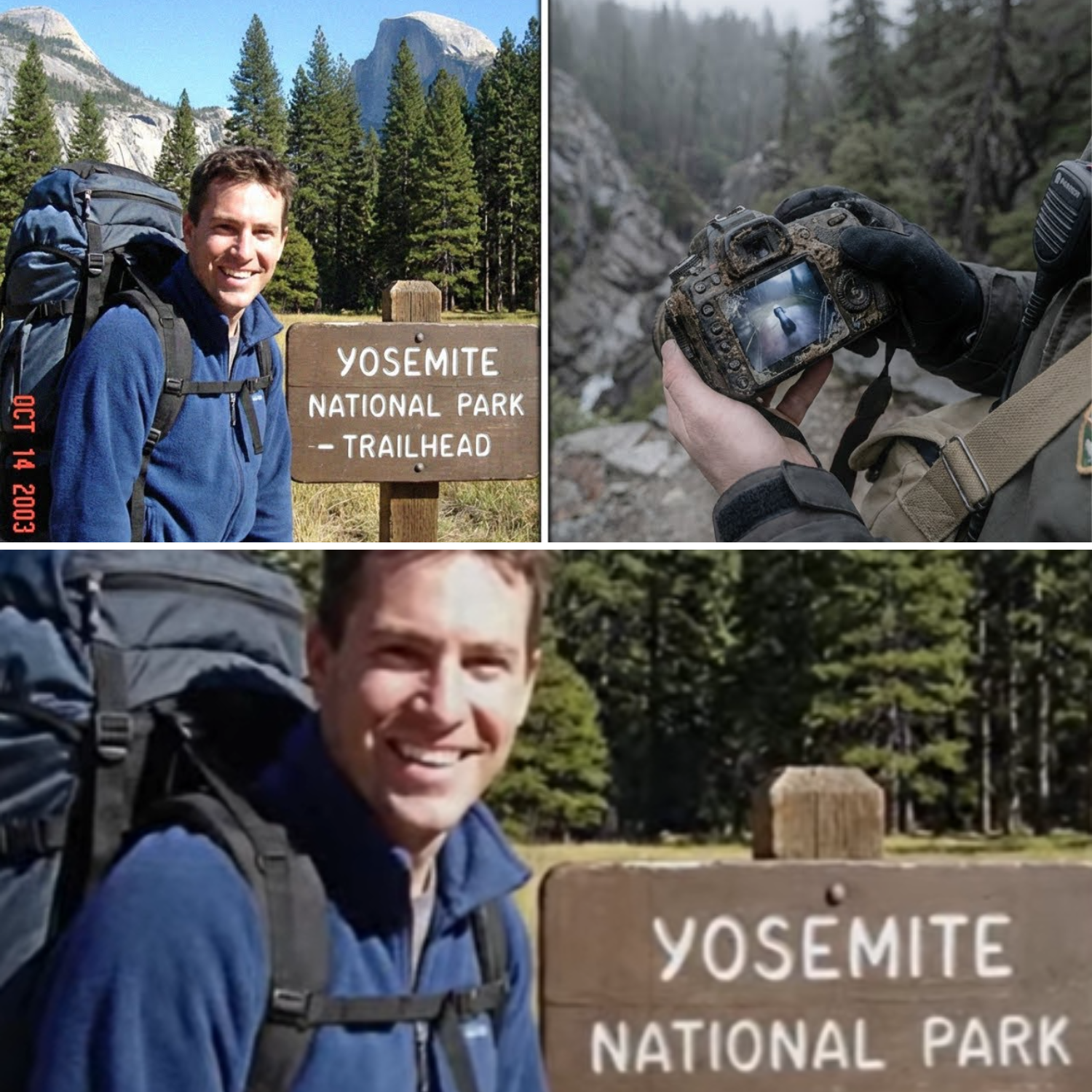

Michael Torres was 33 years old in October 2003, with ten years of hiking experience in Yosemite. Wilderness first responder certified, he was the kind of hiker other people trusted with their lives. His girlfriend, Sarah, described him as methodical, almost obsessively prepared. He had checklists for his checklists, she said. Michael didn’t take risks. That’s what made his disappearance unusual from the very beginning.

October 15th, 2003, started like any other autumn day at Yosemite. Clear skies, temperatures in the low 60s, perfect conditions for the climb to Half Dome. Michael signed into the trail register at 6:47 that morning, telling the ranger he’d be back before dark. Standard route: cables trail to the summit, then down before afternoon weather moved in—an 8 to 10-hour round trip. He carried water, emergency supplies, a first aid kit, and that Canon PowerShot digital camera, one of the first affordable models regular people could buy.

When he didn’t return by 8 PM that evening, Sarah called it in immediately. Not like him, not even close. Search teams deployed at first light the next morning. They found his car in the parking lot, registration paperwork in the glove box, a gym bag in the back seat—everything exactly where it should be. Rangers hiked the entire route twice. Helicopters swept the area with thermal imaging. They checked every ledge, every fall zone, every place someone might slip. Search dogs found nothing.

Three days of intensive searching. Four days, a week—no backpack, no clothing, no disturbed earth, no signs of a fall, no blood, no struggle. Michael Torres had walked into Yosemite National Park on a clear October morning and vanished as completely as if he’d never existed. The investigation went cold within months. Theories emerged, the way they always do when someone disappears without a trace.

“Maybe he staged his own disappearance,” investigators suggested. But his bank accounts were never touched. Every dollar he’d saved was still there. “Maybe he fell somewhere the searchers missed,” but helicopters with thermal imaging should have found a body. “Maybe he wanted to start over somewhere new,” but everyone who knew Michael said that was impossible. He loved Sarah. He loved his work. He had plans for the future. Sarah never believed he’d abandoned her. She came back every year on the anniversary, hiked that same trail, left flowers at the summit.

She kept coming back until 2015. By then, she’d remarried, started a new life. Grief has a way of teaching people when to let go. But Michael’s camera hadn’t let go. It had been waiting in that ravine for 17 years. The ranger who found it in July 2020 almost didn’t pick it up. It just looked like trash at first—another piece of plastic wedged between rocks where Bear Creek Ravine cuts through the eastern wilderness.

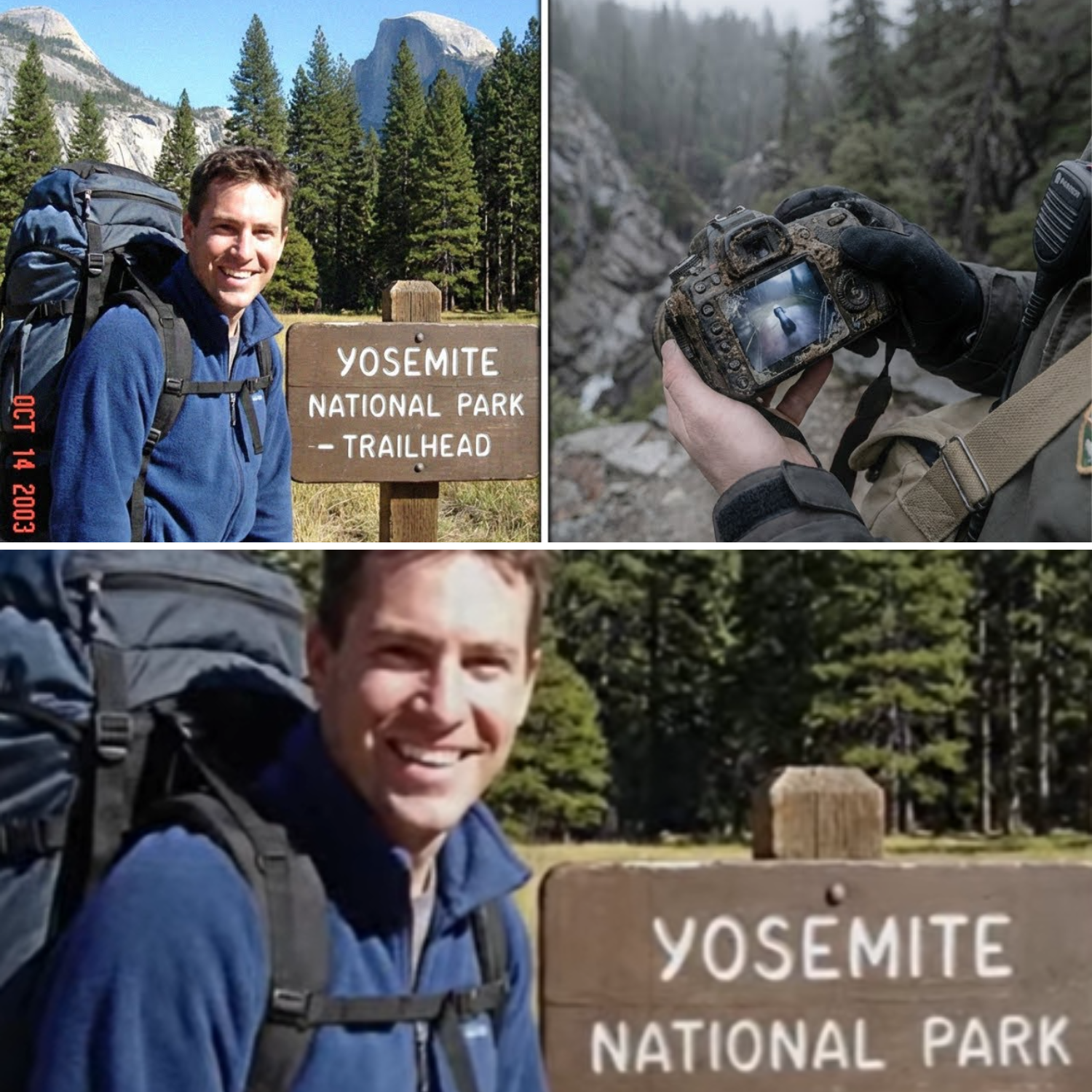

But something about it caught his eye. The shape, maybe. The way morning sunlight hit the cracked screen. He radioed it in as possible evidence before he even knew what he’d found. When they ran the serial number through Canon’s database, the registration came back with a name: Michael Torres. Purchase date: July 2003. The same camera he’d been carrying the day he disappeared.

They sent it to the evidence lab in Sacramento. Seventeen winters of freezing and thawing. Seventeen summers of heat. The battery had corroded into a solid mass of rust. The LCD screen was shattered, water damage throughout. Tech specialists told investigators that data recovery was unlikely, but they managed to extract the memory card. And that’s when everything changed.

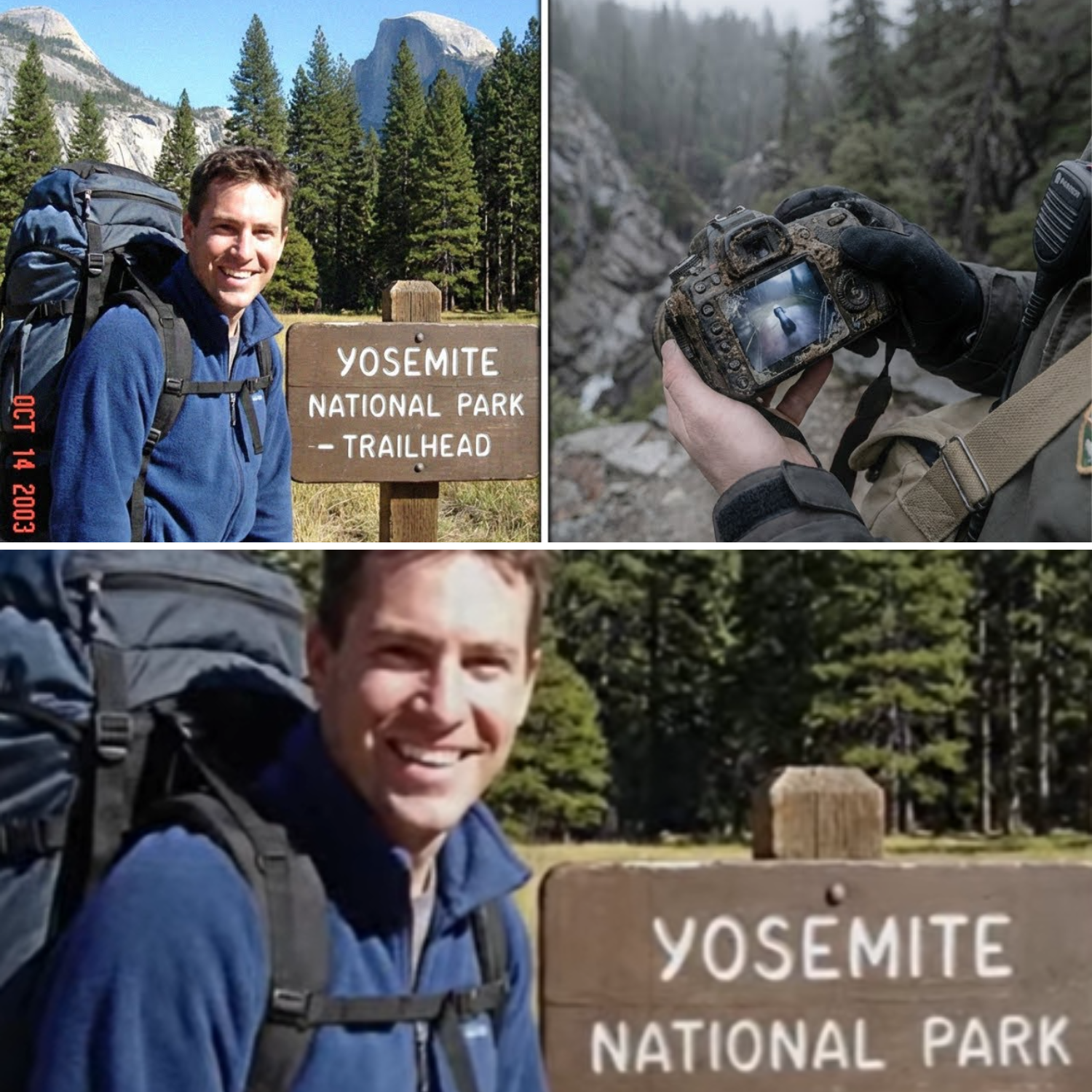

Forty-seven photographs, all taken October 15th, 2003, all timestamped, all preserved despite the years, the weather, and the damage. The first twelve photos were unremarkable, the kind of images any hiker might capture. Michael at the trailhead at 7:02 in the morning. That optimistic early morning smile. Sunlight filtering through Ponderosa pines. Switchbacks at 7:34. View of Nevada Falls at 8:19. Cathedral Peak visible in the distance, perfectly framed. He had a decent eye for composition; he actually knew how to use natural light.

Photo 13, taken at 10:47 in the morning, showed Michael at the summit. He’d extended his arm for a selfie. Behind him, that iconic curved granite dome, the cables visible descending toward the subdome. He looked happy, tired from the four-hour climb, but happy, satisfied. That was the last normal photograph Michael Torres would ever take.

Photo 14 changed everything. Taken at 11:03 in the morning, 16 minutes after his summit selfie, the camera pointed down at bare granite beneath his feet. Just rock, nothing else visible in the frame. The image was slightly out of focus, as if his hands had been unsteady. Why would someone photograph blank granite? Photo 15, taken at 11:04, showed the same granite surface zoomed in closer. This time you could see individual crystals in the rock—a tiny shadow from a cloud passing overhead—but nothing that would explain why Michael felt compelled to document this.

Photos 16-27 told a much stranger story, all taken between 11:05 and 11:19 in the morning. In those 14 minutes, he photographed the same tree, a wind-battered Jeffrey pine growing from a crack in the granite about 30 feet from the summit. Twelve photographs of that exact same tree taken from slightly different angles. You could track Michael’s movement around it, circling, documenting, studying it from every side. But here’s what concerned investigators when they analyzed these images: there was nothing unusual about that tree. It wasn’t diseased, it wasn’t damaged, it wasn’t bent at an odd angle or marked in any way.

Rangers recognized it immediately when they reviewed the photos. Locals called it the Sentinel Pine. It was a landmark. In fact, people used it for directions. Thousands of hikers had photographed it over the years. So, why would an experienced hiker, a man trained in wilderness first response, a person known for his methodical nature, take twelve photographs of an unremarkable tree in 14 minutes? Dr. Rebecca Chen, a wilderness psychology specialist brought in to analyze the photo sequence, spent two weeks studying those tree images.

I’ve read her report. Parts of it were classified, but sections leaked to investigators. She noted that repetitive documentation of a single object typically indicates one of two things: either the subject is experiencing acute paranoia, attempting to capture changes that others can’t perceive, or they’re recording evidence of something they believe others won’t believe without photographic proof. The tree hadn’t changed.

When rangers examined the Sentinel Pine in 2020, it looked identical to how it appeared in Michael’s 2003 photographs. Same branches, same shape, same growth pattern. If Michael was documenting changes, those changes weren’t visible to anyone else. Photo 28, timestamped 12:41 in the afternoon, showed Michael’s boots—just his feet standing on granite, slightly out of focus. The timestamp revealed something troubling: he’d been on the summit for nearly two hours by this point. Most hikers spend perhaps 20 minutes at the top, take their photos, enjoy the view, then begin the descent before afternoon weather moves in. Michael would have known that. He’d hiked this trail dozens of times.

Photo 29, at 1:15 in the afternoon, showed his backpack lying open on the rock, contents visible—water bottles, emergency blanket, first aid kit. The image was sharp, deliberately composed, like he was documenting his supplies, creating an inventory. Photo 30, at 1:16, was a close-up of his watch. The analog face showed 1:16. Why photograph your watch? Why create a record of the time when the camera itself was timestamping every image?

That’s when the photos started showing something worse. Photos 31 through 38 were all taken between 2:23 and 4:47 in the afternoon. More than two hours, and every single one showed the sky—just the sky—sometimes with clouds, sometimes clear blue, sometimes both. But forensic analysts noticed something specific when they examined these images. The angle changed with each photograph. Michael wasn’t standing in one spot pointing the camera upward. He was moving, pacing perhaps, constantly photographing overhead while walking in patterns across the summit. The timestamps revealed irregular intervals, too. Sometimes 30 seconds between photos, sometimes 40 minutes, like he was distracted or waiting or watching for something, taking pictures in response to what he was seeing.

Dr. Chen’s analysis suggested he was tracking something aerial. “The irregular intervals indicated reactive behavior,” she wrote. Taking photographs in response to observed movement or changes, not on a predetermined schedule. But weather records from October 15th, 2003, showed clear skies after 2:00 in the afternoon. No unusual cloud formations, no storm systems anywhere near Yosemite. The FAA confirmed no aircraft were reported in that area. If Michael was tracking something overhead, no one else saw it. Whatever he was photographing, it was invisible to weather satellites and air traffic control.

Photo 39, taken at 5:52 that evening, revealed just how far things had deteriorated. The image showed almost complete darkness. The camera flash had fired, creating that harsh flat light you get with cheap built-in flashes. It illuminated perhaps 12 feet of space. Granite, deep shadows, and the barely visible outline of the cables descending into blackness. Michael was still on the summit, alone in the dark that violated every principle of wilderness safety. Search and rescue teams later confirmed that Michael’s pack inventory included a headlamp. He had the equipment to descend safely. So why hadn’t he started down? Why was he still there seven hours after most hikers would have left, taking flash photographs in darkness?

Photo 40, timestamped 6:34 in the evening, showed something that made investigators deeply uncomfortable. The Jeffrey Pine again, the same tree he’d photographed 12 times earlier that day, but now captured at night, the flash illuminating gnarled branches reaching into darkness. And here’s what forensic photo analysts couldn’t explain: the shadows. This image fell at angles that didn’t correspond to the camera flash position. Light and shadow should be predictable. Flash fires from the camera. Objects cast shadows away from the light source. Basic physics. But the shadows on that tree didn’t match the flash. They fell at wrong angles—multiple angles, actually—as if there were several light sources instead of one.

A forensic photo analyst named Patricia Kim spent three hours attempting to determine where the light was coming from. She wrote in her official report, and I’m quoting directly here: “secondary illumination source, origin unknown, inconsistent with camera flash alone, unable to determine position or type of additional light source.” A second light. Somewhere on that dark summit, something else was producing illumination. Michael’s headlamp perhaps. But if he’d turned on his headlamp, if he had light, why not use it to descend? Why stay on the summit in darkness photographing a tree he’d already documented extensively hours earlier?

Photos 42 through 45 were taken between 8:03 and 9:27 that night. All showed the ground—just granite—photographed with flash in total darkness. All four images were blurred, shaky, like Michael’s hands were unsteady or he was moving erratically while taking the photos. Photo 43 caught his left hand in the frame. You could see his fingers pale in the harsh flashlight, visibly trembling.

Photo 46, timestamped 11:38 that night, was different from the others. The flash had fired, illuminating what appeared to be a rock formation about 15 feet away. But the photograph was taken at an upward angle, as if Michael was lying down or crouching low, pointing the camera at something above him. The image quality was poor. Motion blur distorted most of the frame, but there was something visible in the upper right corner—a dark shape, irregular edges. It could have been a boulder. It could have been a shadow. It could have been nothing at all.

Three separate photo forensics experts examined this image. I spoke with two of them. They couldn’t agree on what they were seeing. One thought it was a rock outcropping. One thought it was camera artifact distortion from the damaged lens. The third refused to speculate, saying only that the image was too degraded for analysis. Photo 47 was the last photograph Michael Torres ever took. At 11:38 at night, 13 hours after reaching the summit, 16 hours after starting his hike, the camera flash fired one final time. The image showed granite, darkness, and something else—a narrow beam of light that wasn’t from the camera flash, a flashlight.

Michael’s flashlight finally turned on after more than six hours of darkness. The beam was directed forward, pointing at something specific, perhaps 10 or 12 feet away. You couldn’t see what the light was illuminating. The angle was wrong. The exposure was wrong. The darkness beyond the flashlight beam was absolute. But you could see that the beam was aimed with purpose, directed at something close, something perhaps that required documentation at 11:38 at night on a mountain summit. After that, nothing. No photo 48, no photo 49. The memory card had capacity for 63 more images. Michael Torres never took another photograph.

Search and rescue teams had been on Half Dome that night. Multiple teams, actually. Dozens of searchers, some on foot, some in helicopters equipped with powerful searchlights. They’d been looking for Michael since the previous evening when Sarah reported him missing. All through the night of October 15th, teams were on that mountain. Not one of them found any trace of Michael Torres. No footprints, no equipment, no signs anyone had been on that summit recently. When search teams reached the top at first light on October 16th, the granite was pristine.

According to those 47 photographs, Michael had been there the entire time, but when searchers arrived, he was gone. The park service brought in specialists to analyze the photo sequence. They wanted to understand what had caused an experienced hiker to behave so irrationally. Why would someone stay on an exposed summit for 16 hours, photograph the same tree 12 times, track empty skies, then spend hours in darkness taking erratic flash photos? The official conclusion was psychological episode, acute paranoia. The report suggested possible psychotic break.

Dr. Chen’s analysis supported this interpretation. The repetitive behavior, the loss of time awareness, the eventual erratic movement patterns—all consistent with severe psychological disturbance. That would have been the explanation. Tragic, but understandable. Solo hiker experiences mental health crisis, makes fatal decisions, falls in darkness somewhere searchers missed. But there were three problems with that theory. First, Michael Torres had no history of mental illness—none whatsoever. No medication, no family history of psychiatric conditions, no prior episodes of any kind. His girlfriend, his friends, his employer, his hiking partners—everyone who knew Michael described him as mentally stable, emotionally grounded, perhaps even boring in his predictability—the kind of person you could count on, the kind of person who didn’t have breakdowns.

Second, the camera’s GPS metadata. Tech specialists managed to recover partial coordinates from 11 of the 47 photographs. All of them placed Michael on Half-Dome Summit, which wasn’t surprising. But here’s what didn’t make sense. The coordinates drifted. Photo 14 showed him at one edge of the summit plateau. Photo 22 showed him 40 feet away. Photo 30 showed him back near the first location. Photo 41 showed him somewhere in between. He was pacing, moving in deliberate patterns across the summit, back and forth. The GPS drift suggested he was either avoiding something, maintaining distance from something, or possibly following something. His movement wasn’t random; it was purposeful, strategic.

Third, and this is perhaps the most troubling detail, the search teams found absolutely nothing on that summit. I’ve spoken with some of those searchers. They’re professionals. They know how to read a landscape, how to spot signs of human presence. If Michael had been on that summit all night, experiencing a psychological episode, there should have been evidence—footprints in the sandy patches, disturbed earth, broken vegetation, dropped equipment, scuff marks on the granite. The summit was pristine. It showed no signs anyone had been there recently.

So either the psychological explanation was correct, and Michael somehow vanished without leaving a single trace from a location being actively searched by dozens of professionals with helicopters and thermal imaging, or something else happened on Half-Dome Summit on the night of October 15th, 2003. Something those 47 photographs captured but couldn’t fully show. The park service quietly updated their protocols after the camera was recovered. Rangers are now required to report any hiker who remains on Half-Dome Summit past 2 in the afternoon. They check the area more frequently during October. They take unusual behavior more seriously.

But they don’t discuss why these changes were made. They don’t mention Michael Torres in their briefings. And they certainly don’t discuss the photographs. Sarah Chen, she’d remarried by the time the camera was found, taken a new name, built a new life, was finally shown the photographs three months after they were recovered. The park service had resisted. Too disturbing, they said. Too many unanswered questions. But she had legal rights to Michael’s effects, and eventually, they had to comply.

She sat in a conference room at park headquarters and scrolled through all 47 images on a laptop computer. Didn’t say anything for almost an hour. Just looked at each photograph, sometimes going back to previous images, sometimes zooming in on details, sometimes just staring at the screen in silence. When she finished, she asked one question: What was he looking at? The ranger presenting the evidence didn’t have an answer. Because Michael didn’t take random photos, Sarah said, “I knew him for six years. I hiked with him dozens of times. I watched him take thousands of photographs. He was deliberate about everything. If he photographed that tree 12 times, it’s because something about that tree was wrong. If he photographed the sky eight times, it’s because something in the sky was wrong.” He was documenting evidence. He was trying to prove that something real was happening to him.

Three weeks later, Sarah hired a private investigator named David Reeves, a former search and rescue specialist, someone who understood wilderness disappearances, knew how to read terrain and evidence. Reeves had worked cases in Yosemite before. He spent two months on this investigation, hiked Half-Dome 17 times, studied the photo locations, interviewed the original search teams from 2003. He compiled a 70-page report that the park service attempted to suppress. Parts of it circulated online.

Anyway, in that report, Reeves noted something specific, something the park service had never made public. Five other hikers had disappeared from Half-Dome Trail between 1998 and 2007. All of them solo hikers. All of them experienced. All of them in October. None of them were ever found. The park service said that was coincidence. Popular trail. They argued dangerous conditions. Statistical probability. People disappear in wilderness areas. It happens.

But Reeves found something else. Two of those five missing hikers had been carrying cameras—digital cameras, same as Michael. Those cameras were never recovered. Never found despite extensive searches of the areas where the hikers vanished. A third hiker, a man named Robert Chen, no relation to Sarah, had told his wife the night before his final hike that something had bothered him on his previous trip to Half-Dome. He kept seeing something moving in the trees, he’d said. She asked what he meant. He said he didn’t know. Just movement, shapes, things that didn’t quite make sense. She’d assumed he meant wildlife—bears or deer. He’d gone back to the summit two days later. He never came home.

Reeves’s report ended with a recommendation: close Half-Dome Summit from mid-October through early November until a thorough investigation could be conducted into the pattern of disappearances. The park service declined. Too much economic impact, they said. Too many permits already issued. No concrete evidence of danger that would justify closure. Michael Torres’s camera sits in an evidence locker in Sacramento. Those 47 photographs have been analyzed by over 30 different experts. Now, psychologists, photo-forensic specialists, wilderness behaviorists, even a few paranormal investigators who somehow obtained access to leaked copies. Nobody agrees on what the images show. Some see a psychological crisis, pure and simple. Some see evidence of something unexplained on that mountain. Some see nothing but tragedy and questions that will never have answers.

Sarah Chen knows what she saw in those photographs. She saw Michael documenting something, trying to prove something, leaving evidence for whoever eventually found his camera. She still hikes sometimes, though never in Yosemite, never alone, and never in October. When people ask why, she just says she prefers company these days. She doesn’t mention the photographs. She doesn’t mention that in photo 47, that final image showing the flashlight beam, if you zoom in close enough, if you adjust the brightness and contrast carefully, there’s something visible at the very edge of where the light reaches—something that could be fabric or skin or fingers or a hand reaching toward the camera from just beyond the darkness.

Park rangers say it’s a rock formation. Photo-forensics specialists say it’s digital noise, sensor artifacts from water damage. Sarah Chen doesn’t say anything at all about it, but she’s never been back to Yosemite since the day she reviewed those 47 photographs. And she’s told friends she never will go back. The mountain keeps its secrets. Whatever Michael Torres encountered on that summit, whatever those photographs documented but couldn’t quite capture, it’s still up there, waiting perhaps for the next solo hiker who stays too long, who sees something they can’t explain, who tries to document proof of something that shouldn’t exist at 8,000 feet.

The camera remains sealed in its evidence box. The case file is marked inactive. Half-Dome Trail opens every spring and closes every winter, and nobody mentions Michael Torres anymore. The photographs exist in a database somewhere accessible only to investigators and researchers with proper clearance. But if you hike that trail in October and you reach the summit and you see that old Jeffrey Pine growing from a crack in the granite, the one the locals call the Sentinel Pine, take your picture and begin your descent. Don’t linger to watch the sunset. Don’t photograph the same tree multiple times. Don’t check your watch. And whatever you do, don’t wait for darkness. Because Michael Torres waited. He stayed and watched and photographed for 16 hours—47 images that documented something, something that made an experienced hiker abandon every rule of wilderness safety. Something that kept him on that summit through sunset and darkness and the long cold October night. Something that three dozen experts still can’t agree on 17 years later.

Forty-seven photographs and then he was gone.