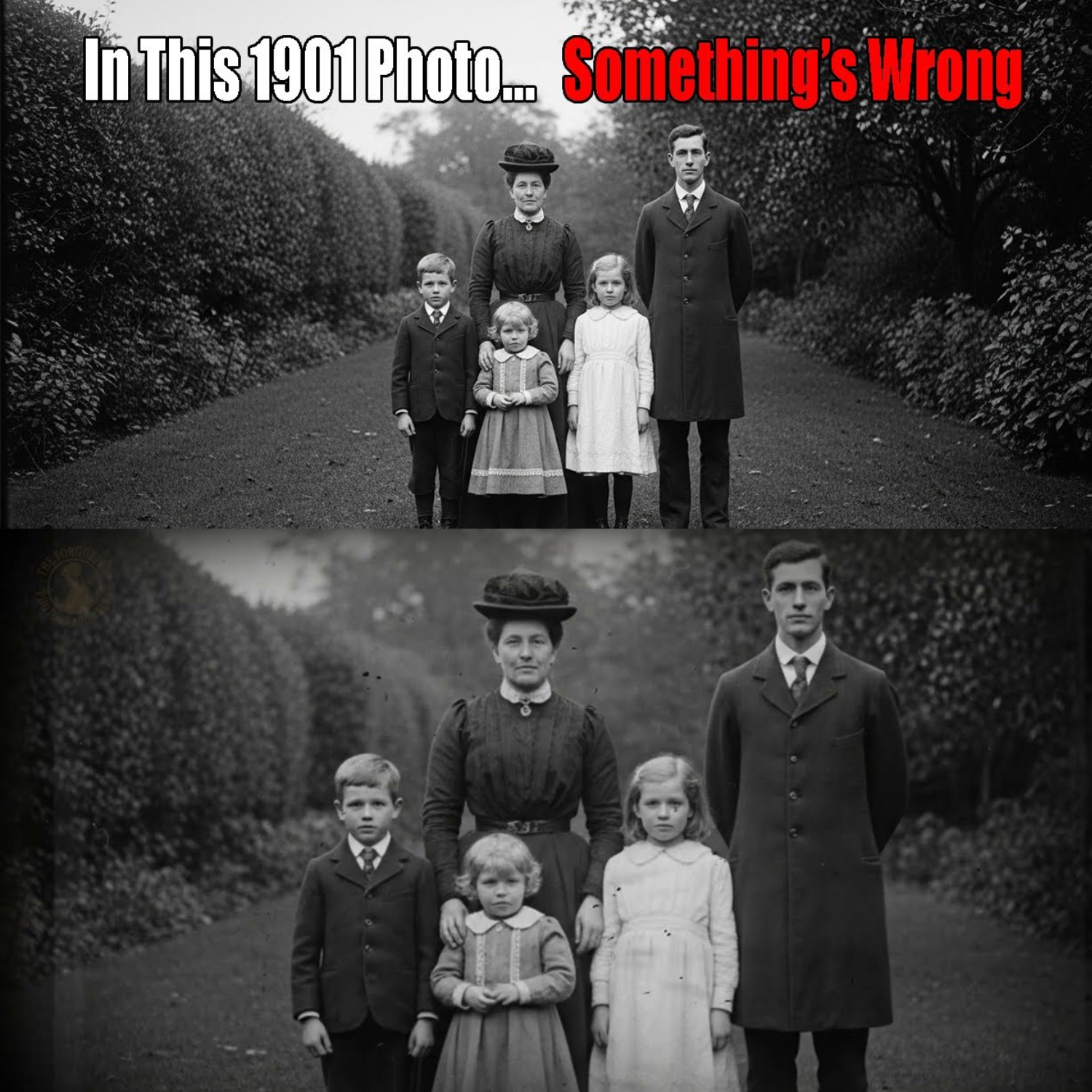

Photo from 1901 Looks Innocent… Until You See the Details

In the quiet suburb of Hampstead Heath, London, on a crisp September afternoon in 1901, Margaret Whitmore, a young widow of 34, carefully positioned her two children in the garden for a photograph. Her son Thomas, seven, and daughter Emily, five, stood obediently beside her, their expressions serious as was customary in Victorian-era portraits. Margaret’s late husband, William, had died tragically two years prior in a factory accident, leaving her determined to preserve every memory of her small family. She had spared no effort in arranging this session with Henry Caldwell, a meticulous photographer whose reputation spanned decades of capturing London families with precision and care.

The camera was a heavy, cumbersome machine, requiring an eight-second exposure. Everyone was to remain perfectly still, every movement calculated to ensure clarity. Margaret recorded each detail in her mind—the angle of the sunlight, the gentle sway of the trees, the delicate laughter she tried to suppress from her children. She was alone with Thomas, Emily, and Mr. Caldwell, or so she believed.

It wasn’t until 87 years later, long after Margaret and her children had passed, that the true story of that day would emerge. In 1988, Jonathan Meyers, a seasoned photograph restorer at the British Museum, began digitizing a collection of Victorian-era images donated by the Whitmore family. Among the countless portraits, one photograph caught his eye, not because of the children’s stiff poses, but because of something profoundly impossible—a figure standing behind the great oak tree in the garden, a figure that should not have existed.

Meyers was meticulous. He magnified every corner of the image, comparing shadows and reflections to Caldwell’s original notes, which described a sunny afternoon with light from the southwest. Shadows in the photograph seemed to bend and fall unnaturally; reflections on Margaret’s silver brooch hinted at a rectangular shape that had no physical counterpart in the garden. Yet it was the figure behind the tree that chilled him to the bone—a person of average height, dressed in materials unknown to 1901, holding an object that emitted its own cold, bluish light.

It defied explanation. Caldwell’s detailed diary confirmed that no one else was present. Margaret’s meticulous records corroborated this. The figure wasn’t a trick of shadows, nor a double exposure. It had the optical density of a real human being, interacting with light in ways that obeyed none of the known physics of the time.

Experts were brought in. Dr. Sarah Chen, a Victorian photography historian, confirmed that the figure’s clothing was made of synthetic fabrics that wouldn’t exist for decades. Professor David Thornton, a physicist, noted that the object the figure held reflected light consistent with liquid crystal displays—technology not practical until the 1970s. Even Maria Santos, a forensic investigator used to digital manipulations, could find no trace of forgery or alteration.

Then, a shocking discovery deepened the mystery. In 2003, during renovations of the Whitmore home, workers uncovered a chest walled up in the attic. Inside were hundreds of letters written by Emily Whitmore between 1940 and 1945. In these letters, Emily described, with haunting clarity, the figure she had glimpsed on that September day—tall, silent, smiling with a gentle sadness, holding a small, glowing rectangular window. She had seen images flickering inside it: machines flying without wings, people in strange clothing, places she couldn’t recognize.

Her mother had scolded her for pointing it out, insisting it was only a child’s imagination. But Emily never forgot. Throughout her life, she experienced fleeting glimpses of people from other times—reflected in windows, passing by trains, vanishing whenever she tried to focus. She never married, instead dedicating her life to the British Museum, perhaps unconsciously drawn to preserve fragments of history and hope to one day understand what she had witnessed.

Scientific investigations continued. In 2018, AI algorithms designed to detect image manipulations confirmed the photograph’s authenticity while also noting light and shadow patterns in the figure’s region that defied known optical laws. In 2019, CERN physicists discovered isotopic anomalies in the silver crystals where the figure stood, as if exposed to entirely different radiation. In 2021, international space agencies, using spectral analysis developed for exoplanets, confirmed that parts of the photograph were captured in slightly different temporal periods.

The figure remains there to this day, silent, a guardian—or perhaps a visitor—out of time, watching, carrying a light from a future no one yet understands. The photograph now resides in the British Museum, drawing thousands each year. Some report intense deja vu; others feel a presence, as if being observed in return. Descendants of the Whitmore family continue a peculiar ritual every September 15th in the old garden, standing in silence for the eight seconds it took Caldwell to capture the original image. Some claim to see the figure again, fleetingly, or even glimpses of overlapping eras, as if time itself had folded into the present.

This is more than a photograph; it is a window into the incomprehensible. It challenges the linearity of time, the solidity of reality, and the limits of human understanding. Margaret Whitmore merely wished to capture a simple memory of her children, but she unwittingly preserved something extraordinary—proof, perhaps, that our universe is far stranger than we can imagine.

Somewhere in the shadows of that old garden, across decades, a silent figure still waits. Observing. Watching. And reminding us that time may not be a straight line, that the past, present, and future might coexist in ways we have yet to comprehend.

No one knows who—or what—it truly was. And maybe that’s the point. Some mysteries are not meant to be solved, only witnessed, their silent weight pressing against the fragile boundaries of human perception. The Whitmore photograph, after more than a century, continues to shock, to haunt, and to awe—a relic of a moment where reality itself seemed to bend.