What Patton Did When He Found Out His Soldiers Executed 50 SS Guards

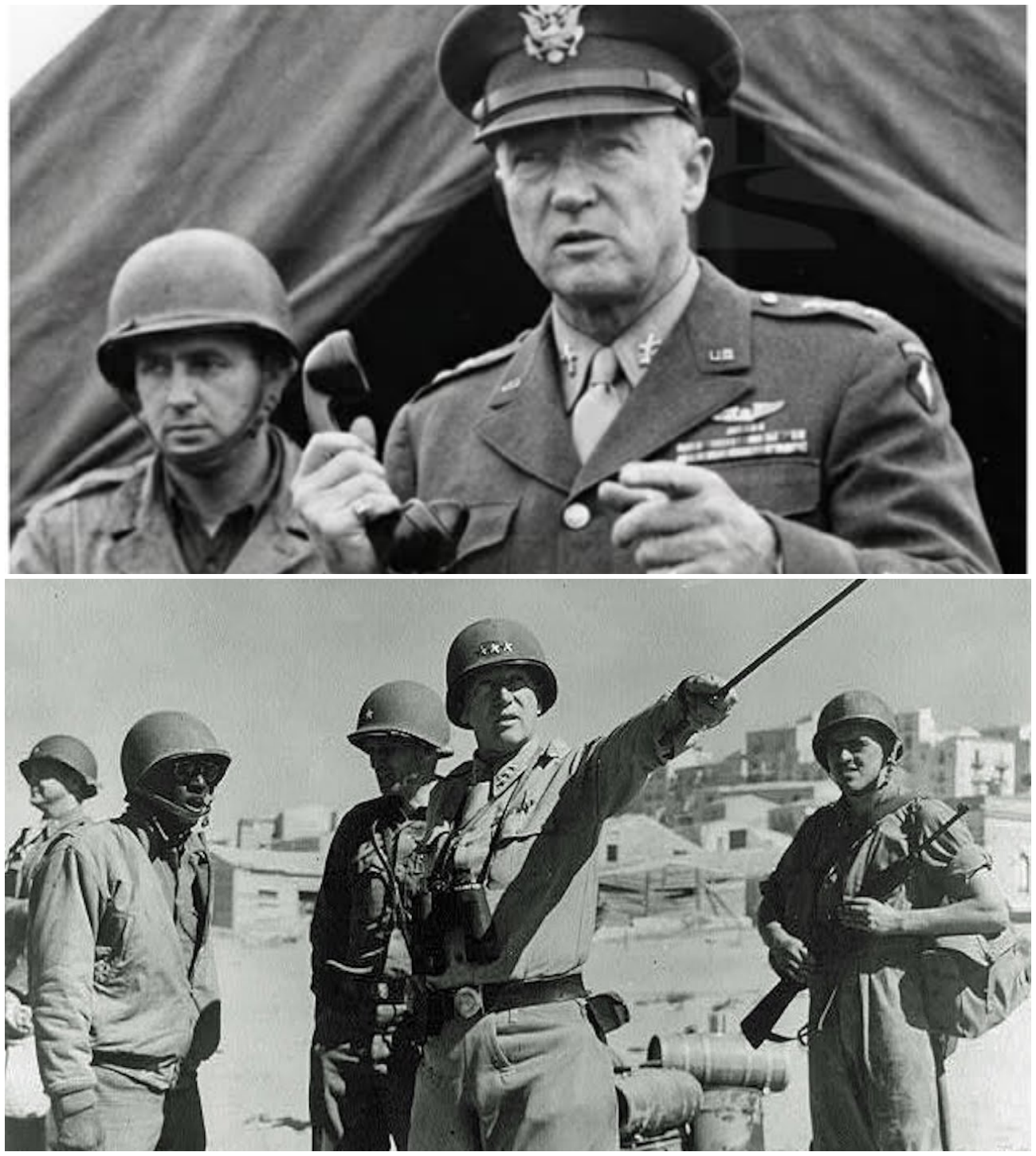

On January 4, 1945, the atmosphere inside the headquarters of the U.S. Third Army in Luxembourg was chilling, not just from the frigid winter air but from the weight of a grave secret. Major General George S. Patton, a figure synonymous with military prowess and decisive action, stood before a fireplace in a converted chateau, unaware that a storm was brewing in the form of a thick Manila folder stamped “Top Secret.”

As a major from the Inspector General’s office approached, the tension in the room escalated. The major was visibly nervous, clutching the folder that contained damning evidence of a mass execution—not by the Nazis, but by American soldiers. Inside were sworn statements, ballistic reports, and a list of names detailing a horrific war crime that would send shockwaves through the ranks of the U.S. Army.

A Shocking Revelation

Patton, known for his commanding presence on the battlefield, turned to face the major. He expected to hear an account of valor or perhaps a commendation for his troops. Instead, he was confronted with the dark reality of what had transpired during the brutal winter of 1944. The major cleared his throat, prepared to deliver the news of a massacre that had occurred in the village of Chenon.

As he began to explain the details of the incident—how American soldiers had executed approximately 60 German SS guards after they had surrendered—Patton’s demeanor shifted. The major anticipated an explosion of outrage, a demand for justice, or at least a call for a court-martial. But what happened next was unexpected.

The Decision to Burn the Evidence

Instead of opening the folder or demanding further details, Patton reached for the file and walked toward the flames of the fireplace. The major watched in stunned silence as Patton prepared to incinerate the evidence of an American war crime. In that moment, the general made a decision that would bury a dark secret for decades.

To understand Patton’s actions, one must consider the context of the time. The winter of 1944 was brutal, marked by the coldest temperatures in thirty years. Soldiers faced not only the enemy but also the psychological toll of combat. The Battle of the Bulge was not merely a military offensive; it was a descent into chaos, where paranoia and fear ran rampant among the American troops.

The Aftermath of Malmedy

The psychological strain on the soldiers intensified following the Malmedy Massacre, where 84 American prisoners of war were executed by SS troops. The brutality of that event reverberated throughout the American lines, igniting a visceral rage. The narrative of the “clean war” began to unravel, as soldiers grappled with the reality that their enemies were not just soldiers but ideological fanatics who would show no mercy.

In the wake of Malmedy, the unspoken rule among American troops became clear: the SS were not soldiers but animals. This mindset created a dangerous justification for violence against captured enemy combatants. The illusion of moral superiority began to fade, replaced by a brutal reality where the lines between right and wrong blurred.

The Execution at Chenon

On January 1, 1945, just two weeks after the Malmedy Massacre, the 11th Armored Division engaged in fierce fighting in the village of Chenon. After securing the area, American soldiers captured a group of German soldiers, including numerous SS members. Instead of treating them as prisoners of war, the soldiers marched them into a snowy field and executed them in cold blood.

Eyewitness accounts describe the scene: an American machine gunner methodically set up his weapon, and with the order given, opened fire on the disarmed prisoners. The chilling echoes of gunfire filled the air as the snow turned red, marking a horrific act that mirrored the atrocities committed by the Nazis.

The Investigation

The massacre did not go unnoticed. Rumors spread quickly, and the Inspector General’s office launched a formal inquiry. Within 48 hours, investigators gathered sworn statements from civilians and fellow soldiers, creating a thick dossier of evidence that named the unit responsible and outlined the charges of murder.

The implications of this investigation were profound. If brought to trial, the officers responsible could face the death penalty. The potential for a propaganda disaster loomed large, threatening to undermine the moral high ground that the United States had claimed in the war against fascism.

Patton’s Controversial Choice

When the investigation file landed on Patton’s desk, the weight of the decision before him was immense. The major stood by, anticipating an outburst or a call for justice. Instead, Patton calmly assessed the situation and made a choice that would forever alter the course of history.

“There are no snipers in this army,” he declared, dismissing the allegations against his men. “And I won’t have my men prosecuted for killing the sons of [expletive] who killed our boys.” With that, he tossed the file into the fire, watching as the evidence of the massacre turned to ash.

The Consequences of Silence

Patton’s decision to bury the evidence had immediate consequences. The soldiers of the 11th Armored Division returned to their tanks, emboldened by the knowledge that they would not face repercussions for their actions. The rumor spread through the ranks: the old man has our back. This belief led to a more aggressive and brutal approach to combat, as the inhibition against killing prisoners vanished.

The moral fallout from this decision was profound. Young men who had come to Europe to liberate oppressed peoples were now given tacit approval to act as executioners. The stain of the Chenon massacre settled deep into the fabric of the unit, creating a dark bond among soldiers who knew they had gotten away with murder.

The Legacy of Patton’s Decision

In the years following the war, the narrative surrounding the Malmedy Massacre became well-documented, while the Chenon massacre faded into obscurity. The history books celebrated the heroes of the Battle of the Bulge, glossing over the darker aspects of their actions. The decision to erase the Chenon massacre established a dangerous precedent—one where victor’s justice prevailed, and war crimes were only prosecuted when one side lost.

It wasn’t until decades later, when classified archives were opened and veterans began to share their stories, that the full truth of Patton’s actions emerged. The strategic implications of his decision had a lasting impact on the legacy of the American military during World War II, revealing the complexities of war and the moral ambiguities faced by those in command.

Conclusion: The Cost of War

George S. Patton is often remembered as a heroic figure, a knight in shining armor who fought valiantly against tyranny. However, the truth is far more complicated. On that cold January morning, he made a choice that prioritized the loyalty of his men over the principles of justice and morality. While he saved the soldiers of the 11th Armored from prosecution, he could not save them from the haunting memories of their actions.

As we reflect on the sacrifices made during World War II, we must recognize that war is not a clean fight between good and evil. It is a descent into chaos where even the best of men can commit the worst of acts. Patton’s fire may have destroyed the evidence of a crime, but it could not erase the moral complexities and the heavy toll of war on the human soul. The legacy of that decision serves as a reminder that the line between hero and villain is often drawn in ash, and the true cost of war extends far beyond the battlefield.