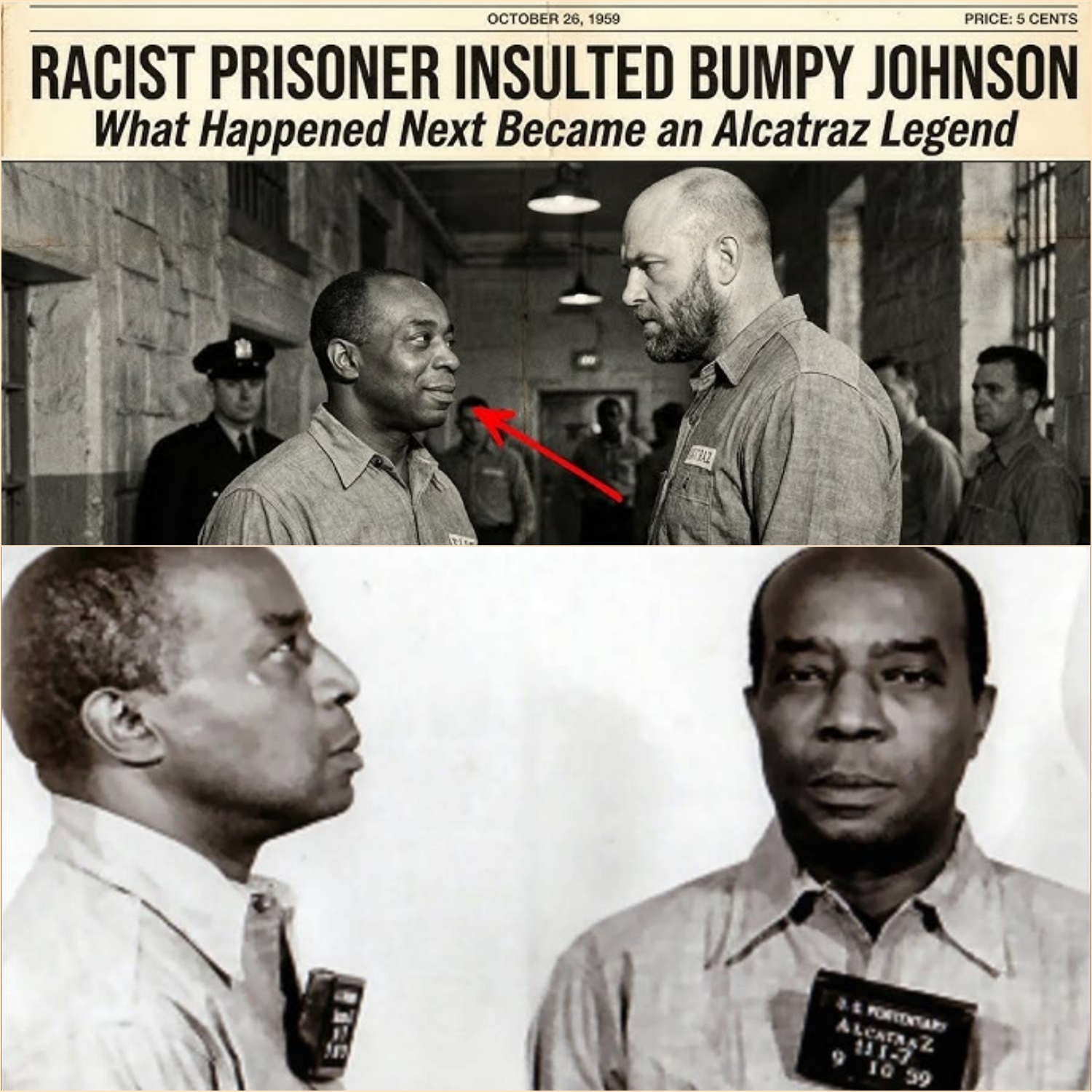

1959: A Racist Prisoner Insulted Bumpy Johnson — He Smiled, Then Everything Ended

.

.

.

1959: The Racist Prisoner Tried to Humiliate Bumpy Johnson — He Smiled, Then Everything Ended

In Alcatraz, respect wasn’t an idea. It was an economy.

Men traded cigarettes, favors, information, and silence—because silence could buy safety, and safety was the one thing the Rock didn’t hand out for free. On the mainland, reputation traveled slowly, diluted by distance and city noise. On Alcatraz, reputation arrived ahead of you like weather. Every man felt it before he ever saw your face.

That’s why the cafeteria could go quiet without a guard saying a word. That’s why a tray sliding across a metal counter could sound like a warning. That’s why a smile—on the wrong face at the wrong moment—could change the atmosphere of a whole room.

It was October 1959, and the air on the island always carried the same sharp ingredients: salt, cold steel, and the faint exhaust of boats crossing the bay. From a distance, Alcatraz looked like a museum of punishment—gray stone, narrow windows, a lighthouse, a waterline that felt like a boundary between the living and the forgotten.

Inside, it was a machine.

It ran on schedules and routines. It ran on headcounts and keys. It ran on men who learned quickly that there were two kinds of power in prison: the power that wore a uniform, and the power that wore nothing but patience.

Bumpy Johnson understood both.

He had been on the Rock since 1953, long enough to know that Alcatraz didn’t “fix” men. It contained them. It separated them from what they loved and what they could control until their influence dried up. It was designed to break networks, not bones.

But bones got broken anyway. Violence never disappeared. It just became smarter.

In a place where a single fight could earn you weeks in the hole—solitary, bread and water, a concrete box where time turned on itself—men learned to deliver damage efficiently, or not at all. They learned to threaten without speaking. They learned to settle disputes with looks and timing and the occasional object that appeared in a hand too quickly for anyone to swear to seeing it.

And they learned to test.

They tested each other because the prison did not allow comfort. It did not allow neutrality. If you weren’t making a statement with your existence, someone else would make it for you.

That’s where the story begins: not with a punch, not with a weapon, but with a man deciding that the quietest person in the room must be the easiest target.

He chose wrong.

1. The Rock and the Rules

Alcatraz didn’t feel like other prisons. It felt like the federal government had stopped pretending.

No rehabilitation slogans. No soft lighting. No polite pretense that the place was meant to build you into something better. The Rock existed for containment—pure and unapologetic. If you were too violent, too influential, too willing to turn a normal prison into your personal kingdom, you were shipped out to the island where even the water didn’t want you.

The prison held just over two hundred fifty men at a time, not because it couldn’t cram more into the cellblocks, but because control required space. Less crowding meant fewer chaotic collisions. It meant guards could watch angles. It meant routines could be enforced like law.

You woke up when they told you. You ate when they told you. You moved when the whistle said move. Even recreation was measured like medicine—an hour in the yard, a lap around the perimeter, the bay wind cutting through your shirt like it wanted to remind you what freedom felt like.

Men survived by learning the subtle architecture of the place:

where the guards stood during meals,

how long it took a man to cross the cafeteria floor,

which corners were watched and which were merely observed,

which guards enforced rules and which only pretended to.

Alcatraz punished violence quickly. That was the point.

But prison had a second economy running under the official one, and it was older than any set of regulations: respect.

Respect didn’t mean politeness. It meant calculation.

Who could you insult and live?

Who could you steal from and keep your teeth?

Who could you bump in the shower and still sleep that night?

That economy never stopped operating.

It just got quieter.

And in quiet places, men like Bumpy Johnson lasted longer than loud ones.

2. Who Bumpy Johnson Was in a Place Like This

By 1959, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson was in his mid-fifties. The gray had started to win in his hair. Prison routine had tightened his body into a smaller version of the man Harlem remembered—less flash, more density. But age on Alcatraz didn’t mean weakness. It meant experience.

Bumpy had never been the kind of gangster who performed for crowds. He didn’t rely on loud intimidation, because loud intimidation attracted attention. He relied on structure—relationships, numbers, leverage. He was known to read constantly. Poetry, philosophy, anything that sharpened the mind. He spoke carefully. He listened more than he talked.

Men who needed to announce themselves were often men who couldn’t survive without noise. Bumpy’s silence was not emptiness. It was control.

On the streets, that control had made him something larger than a criminal in the eyes of many in Harlem: a figure who negotiated, who organized, who enforced order in a world that often had none.

On Alcatraz, the myth traveled faster than the paperwork.

Black inmates saw him as something rare in a federal prison: a man who carried dignity like a weapon. He didn’t plead with guards. He didn’t beg for favors. He didn’t let insults land without consequence. But he also didn’t throw himself into pointless battles. He chose his moments like a chess player chooses sacrifices.

White inmates watched him differently. Some saw him as a problem—someone whose reputation could build loyalty across cellblocks. Some saw him as a curiosity—an older black man in a place dominated by hard white cons who assumed dominance was their natural position.

And some saw him as an opportunity.

Because they mistook calm for fear.

3. The Bully: Eric Pollson and the Logic of Hate

There are men who become violent because they are angry.

And there are men who become violent because they have a belief system that tells them violence is right.

The man in this story—known among inmates as Eric Pollson—was built like an engine block. Big, slow-moving, deliberate. He had the posture of someone who expected people to step aside.

The worst part wasn’t his size. It was his certainty.

According to the stories men traded about him, Pollson had committed murders during robberies on the outside and had targeted black victims specifically. Inside the prison, he carried the same ideology like a religion. He believed dominance was a birthright. He believed cruelty was enforcement.

But he was not foolish. He didn’t explode randomly. He did what the most dangerous inmates always did: he studied the rules and attacked in the gaps.

He harassed in low voices when guards were a few feet too far. He “accidentally” spilled food. He bumped shoulders in corridors. He made insults sound like jokes. He chose moments that could be dismissed as misunderstandings.

Some guards didn’t like him, but they liked paperwork less. Some guards—quietly—shared enough of his worldview to tolerate it. Either way, he learned that certain behavior could continue as long as it did not become a crisis that embarrassed the institution.

Pollson thrived on that tolerance.

He used it the way a man uses a weapon he knows won’t be taken away.

Until he aimed it at someone who had survived weapons his whole life.

4. The First Test: The Pie

The first insult was almost laughably small, which is how these things always begin.

It was a Friday, mid-October, lunch hour in the Alcatraz cafeteria. Metal trays. Long tables bolted to the floor. Guards posted along the walls, watching angles, watching hands.

Bumpy sat with a few other black inmates, eating without conversation. That wasn’t unusual. Men talked less on the Rock. Talking often led to trouble.

Pollson walked past Bumpy’s table like he owned the aisle.

He didn’t stop. He didn’t speak.

He reached down and took the dessert off Bumpy’s tray—an institutional slice of apple pie. The kind of thing no one would risk punishment over if it weren’t for what it meant.

Then he kept walking.

He sat at his own table and ate it slowly, watching Bumpy like a man watching a fuse burn.

The room noticed. It always noticed. In prison, a stolen dessert could be an invitation to war. It was a way to say: I can take from you in front of everyone and you can’t stop me.

Bumpy looked at the empty space on his tray.

He looked at Pollson.

Then he went back to eating, as if the pie had never existed.

No confrontation. No posture. No “what did you just do?”

Nothing.

The men at Bumpy’s table stiffened. Some tightened their jaws. One moved his hands slightly as if preparing for something.

But Bumpy’s body stayed calm. His shoulders did not rise. His face did not change.

To a certain kind of man, that silence looks like surrender.

To another kind of man, it looks like a trap being set.

Pollson didn’t understand the difference.

5. The Second Test: The Showers

Three days later, the next incident came where the air was thick with steam and men kept their eyes forward.

Communal showers were a place for humiliation—easy to deny, hard to prove. The floor was slick. Movement was close. A shove could be blamed on water and accident. An insult could be swallowed by echo.

Bumpy stood under the spray when Pollson entered.

Plenty of open heads. Plenty of space.

Pollson chose Bumpy anyway.

He moved straight toward him and shoved him hard enough to make him slip. Not a playful bump. A real push meant to put a man on the ground.

Bumpy caught himself against the wall.

Pollson leaned in and spoke low, just loud enough for the nearby inmates to hear and just soft enough that a guard at the doorway wouldn’t.

“That’s my shower.”

Then came the racial insult—deliberate, ugly, unmistakable.

Bumpy straightened slowly, water running down his face like sweat.

He looked at Pollson for several seconds.

It wasn’t a stare of panic. It was a stare of evaluation. Like he was measuring Pollson’s breathing, Pollson’s confidence, Pollson’s belief that nothing would happen.

Then Bumpy stepped aside, moved to another shower, and finished washing.

Still no words.

The room felt off afterward. Men avoided each other’s eyes. Even those who didn’t like Bumpy understood what they’d just witnessed: a bully had shoved a man of reputation, and the man of reputation had chosen restraint.

Restraint is unsettling in prison. It suggests calculation.

And calculation suggests consequences.

Pollson, however, only heard one message:

He won’t do anything.

So he escalated again.

6. The Third Test: The Yard

Two days later, in the recreation yard, Pollson made it public.

The yard was cold and gray, bay wind pressing through prison clothes. Inmates walked laps around the perimeter like slow planets orbiting a center that didn’t care.

Bumpy walked with two others when Pollson stepped into his path and stopped.

Blocked him.

Didn’t move.

“You walk around,” Pollson said, loud enough this time for nearby men to hear.

Another insult followed. Another deliberate attempt to force Bumpy into choosing: submit or explode.

Bumpy stopped.

He looked at Pollson.

He paused long enough for the moment to become a scene.

Then he stepped off the path and walked around him.

No words. No visible anger.

Pollson laughed, and the laughter wasn’t joy. It was triumph. It was the sound of a man who believed he had just rewritten the hierarchy of the yard.

That night, the prison buzzed in whispers.

Some said Bumpy was slipping. Some said age had caught him. Some said Pollson had broken him.

But the men who understood the quiet mechanics of prison politics recognized something else: Bumpy had not been retreating.

He had been allowing Pollson to build confidence.

Confidence makes men careless.

Carelessness creates openings.

7. The Wrong Target: Robert Jackson

Everything might have stayed in that ugly pattern—harassment aimed upward, a slow tug-of-war over reputation—if Pollson hadn’t done what bullies always do when they feel untouchable.

He turned his cruelty downward.

The next afternoon in the yard, a young inmate named Robert Jackson sat alone on a bench with a book in his hands. Twenty-three, small frame, serving time for fraud—nonviolent, not connected, not protected. Just a kid trying to disappear into pages until the hour ended.

Pollson saw him and approached without hesitation.

He asked what he was reading—didn’t wait for an answer. He snatched the book and mocked him for reading, mocked him for thinking, mocked him for being small.

Jackson stood slowly and asked for it back. Polite. Careful.

Pollson swung the book across Jackson’s face hard enough to knock him backward off the bench.

Jackson hit the ground, blood on his lip.

Pollson tossed the book into a puddle near a drain and laughed.

A guard stepped in late. Late enough that the message had already landed. Early enough to keep the consequences small.

Pollson got a warning. Lost a single day of yard time.

Jackson went to the infirmary and came back with bruises and the knowledge that he was still alone.

Something changed in the prison after that.

Because harassment aimed at Bumpy was one thing. Men could argue about pride and ego and old reputations. But cruelty aimed at an unprotected kid was different.

It wasn’t a challenge anymore.

It was predation.

That night, Bumpy sat with other inmates and listened. He didn’t interrupt. He didn’t perform outrage. He absorbed details the way he always did.

Then he spoke—calm, measured, as if he was stating tomorrow’s weather.

He said Pollson would learn something at lunch.

Not as a threat shouted into the air.

As a conclusion.

Then Bumpy stopped talking.

And in Alcatraz, silence after a sentence like that was louder than a fight.

8. The Cafeteria: Where Violence Had to Be Smart

The Alcatraz cafeteria was designed for control.

Long tables bolted down. Benches fixed. Clear sightlines. Guards on raised platforms. Movements scheduled like train arrivals. Forty-five minutes in, forty-five minutes out.

In a place like that, violence wasn’t impossible. It was simply expensive. If you fought there, you were choosing consequences.

That’s what made the next day feel heavy even before anything happened.

Friday, October 23rd, 1959.

Lunch began like every other lunch. Trays slid. Men filed in by number. Conversations stayed low. Forks scraped. A guard shouted at someone to keep moving.

Bumpy took his tray and sat at his assigned table with three other inmates. He ate slowly, head lowered, as if the world around him didn’t matter.

Two minutes later, Pollson entered.

Same heavy steps. Same confident posture.

But this time he didn’t go to his own table.

He walked straight toward Bumpy’s and sat directly across from him—uninvited, too close, deliberate.

He slammed his tray down hard enough to draw attention. Nearby conversations slowed. Eyes lifted.

Pollson began talking loudly—mocking Bumpy’s reputation, mocking his race, trying to turn the whole cafeteria into an audience.

Bumpy kept eating.

Didn’t look up.

That silence irritated Pollson more than any insult would have. Men like Pollson needed reaction. Reaction proved power. Reaction meant control.

So Pollson leaned forward and demanded one.

Then—because bullies always return to the easiest prey—he turned and called out toward Robert Jackson, several tables away.

Jackson’s face was still bruised.

Pollson mocked him again and threatened to come over and repeat what he’d done.

Jackson stared at his tray and did not answer.

Some men started to rise. Guards barked for everyone to stay seated.

And that’s when Bumpy stood.

He rose calmly—no rush, no dramatic movement. The kind of motion that makes a room freeze because it doesn’t look emotional. It looks decided.

What happened next took only seconds. Witnesses later described it as fast and controlled—no wild swinging, no chaos, no shouting from Bumpy. Just a short movement, an immediate result, and then Bumpy stepping back as guards rushed in.

Pollson went down.

The cafeteria erupted.

Boots hit concrete. Whistles blew. Guards swarmed the table. Men were ordered to sit, hands visible, eyes down.

Bumpy did not resist. He raised his hands. He allowed himself to be taken down, cuffed, dragged away.

Only then—only after the action was finished and control was back in the guards’ hands—did he speak.

Not loudly. Not for drama.

Just enough for Pollson to hear. Just enough for the men closest to hear.

A sentence meant to last longer than bruises and punishment.

“Touch that young brother again,” he said, voice steady, “and next time you won’t visit a doctor.”

Then he went silent.

And the cafeteria went silent too—not because the guards demanded it, but because everyone understood something had been settled.

Not a fight.

A boundary.

9. The Aftermath: Solitary, Statements, and a Quiet Admission

Bumpy Johnson was taken straight to solitary confinement.

No conversation. No negotiation. Just procedure.

Solitary on Alcatraz was a concrete box designed to punish thought. A steel door. A dim light. The absence of time markers. The kind of silence that makes your own breathing feel like noise.

Violence on the Rock was always investigated. Guards interviewed guards. Kitchen staff were questioned. Inmates were pulled aside one by one and asked what they saw, what they heard, what they knew about the days leading up to it.

And what emerged—according to the way the story has been told in prison lore—was not a sudden explosion. It was a pattern.

Food taken.

Shoves in the showers.

Public humiliation in the yard.

A younger inmate assaulted for the entertainment of a larger man.

Too many stories matched. Too many details overlapped. Even administrators who wanted to keep things simple couldn’t ignore the consistency.

When Bumpy gave his statement, it was brief. Controlled. Unemotional.

He said he had defended himself and another inmate. That guards had failed to stop the harassment. That when the threat became public and immediate, he ended it.

No apology. No grandstanding.

Just facts.

Under normal circumstances, violence inside Alcatraz meant added years—sometimes a lot of them. Possession of a weapon meant more trouble than most men could survive.

But this time, the punishment—according to many retellings—was comparatively limited: time in solitary, yes, but no additional years.

A quiet outcome that functioned like an unspoken admission: the prison knew Pollson had been a problem, and the prison knew it had failed to stop him.

So it punished Bumpy enough to preserve the appearance of control—because institutions protect their image the same way men do—but not enough to invite deeper questions.

And when Pollson recovered, he was transferred out.

Not as a public announcement. Not as a confession. Just a problem moved elsewhere.

10. What Changed on the Rock

Pollson survived.

But he didn’t remain the man who had walked through the cafeteria with confidence.

Men who saw him afterward described a shift that was more telling than any injury: he became quieter. He stopped posturing. He stopped selecting targets with the same certainty. The big body was still there, but the belief that size made him untouchable was gone.

More important than Pollson’s change was what stopped entirely.

The racial harassment that had been tolerated—the whispered slurs, the casual humiliations, the “accidents”—ended abruptly.

Not slowly.

Not after policy memos.

Immediately.

Prisons often claim rules create safety. In truth, safety is usually created by consequences that are understood without explanation.

Bumpy’s status changed as well.

Before, he was respected.

After, he became untouchable in a different way—not because he walked around threatening men, but because everyone understood what his silence meant.

He had been insulted. He had been shoved. He had been publicly challenged.

He did nothing.

Until the moment he decided the line had been crossed.

That is the kind of power even violent men recognize: power that doesn’t need to prove itself repeatedly.

Younger inmates treated him with a reverence that wasn’t worship but gratitude. He had protected someone who could not protect himself. And he had done it without asking for loyalty in return.

White inmates kept their distance—not always out of fear, sometimes out of calculation. They understood Bumpy wasn’t impulsive. He wasn’t emotional. He didn’t act because he was provoked; he acted because he chose a moment.

Even the guards—subtly—shifted. Less tolerance for harassment. More attention when tensions rose. Not favoritism, exactly. More like awareness: another failure could lead to another moment they couldn’t control.

From that day forward, Alcatraz adjusted around Bumpy Johnson. Not with announcements. With the quiet behavior of men who had watched what happens when authority leaves a gap and someone else fills it.

11. The Real Lesson: Patience as a Weapon

People often misunderstand stories like this.

They think it’s about domination, or ego, or the romance of prison violence.

It’s not.

At its core, it’s about boundaries in a system that routinely fails to protect the vulnerable.

Bumpy didn’t react when he was insulted. He didn’t strike when he was shoved. He didn’t move when he was humiliated.

Each moment of restraint added weight to what would come next.

Because waiting wasn’t weakness. It was positioning.

He allowed his opponent to believe the wrong story—that silence meant fear, that patience meant surrender, that age meant decline.

By the time the truth arrived, it arrived as conclusion, not argument.

That’s why the story traveled—from cellblocks to yards, from Alcatraz to other federal prisons. Men repeated it not because they loved violence, but because they understood consequence. They understood that some warnings only need to be spoken once.

In a place built to contain the most dangerous men in America, Bumpy Johnson didn’t win because he was the biggest.

He won because he knew something the Rock taught every day:

The loudest man in prison isn’t always the most powerful one.

Sometimes the most dangerous man is the one who stays quiet long enough for you to underestimate him—

and then smiles.