🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸The Spinning Giants: Flywheels That Stored Dangerous Power

In the late 19th century, the heart of many industrial factories pulsed with the relentless energy of massive flywheels—colossal, spinning giants that powered entire production lines. But these behemoths, seemingly essential to the smooth functioning of mills and factories, held within them an unimaginable danger. One particularly harrowing incident would expose the deadly force contained within these machines, a force that could tear factories apart in an instant.

In 1891, in the heart of Manchester, New Hampshire, the Amoske Manufacturing Company faced a disaster that would reverberate throughout the industrial world. The engine room shook violently as a 56-ton flywheel shattered at full speed. Steam burst from ruptured pipes, and iron fragments flew through brick walls, killing three men instantly. The catastrophic failure of that flywheel released an immense, concentrated energy, proving just how dangerous these machines had become.

The Power of the Flywheel

At first glance, a flywheel appears deceptively simple: a heavy, rotating disk that stores energy. But in an industrial setting, it played a critical role. Steam power, though revolutionary, was inherently uneven. The power generated by steam engines came in pulses—each piston stroke surged, then fell. This inconsistency wreaked havoc on production lines in textile mills, breaking threads, jamming looms, and ruining product.

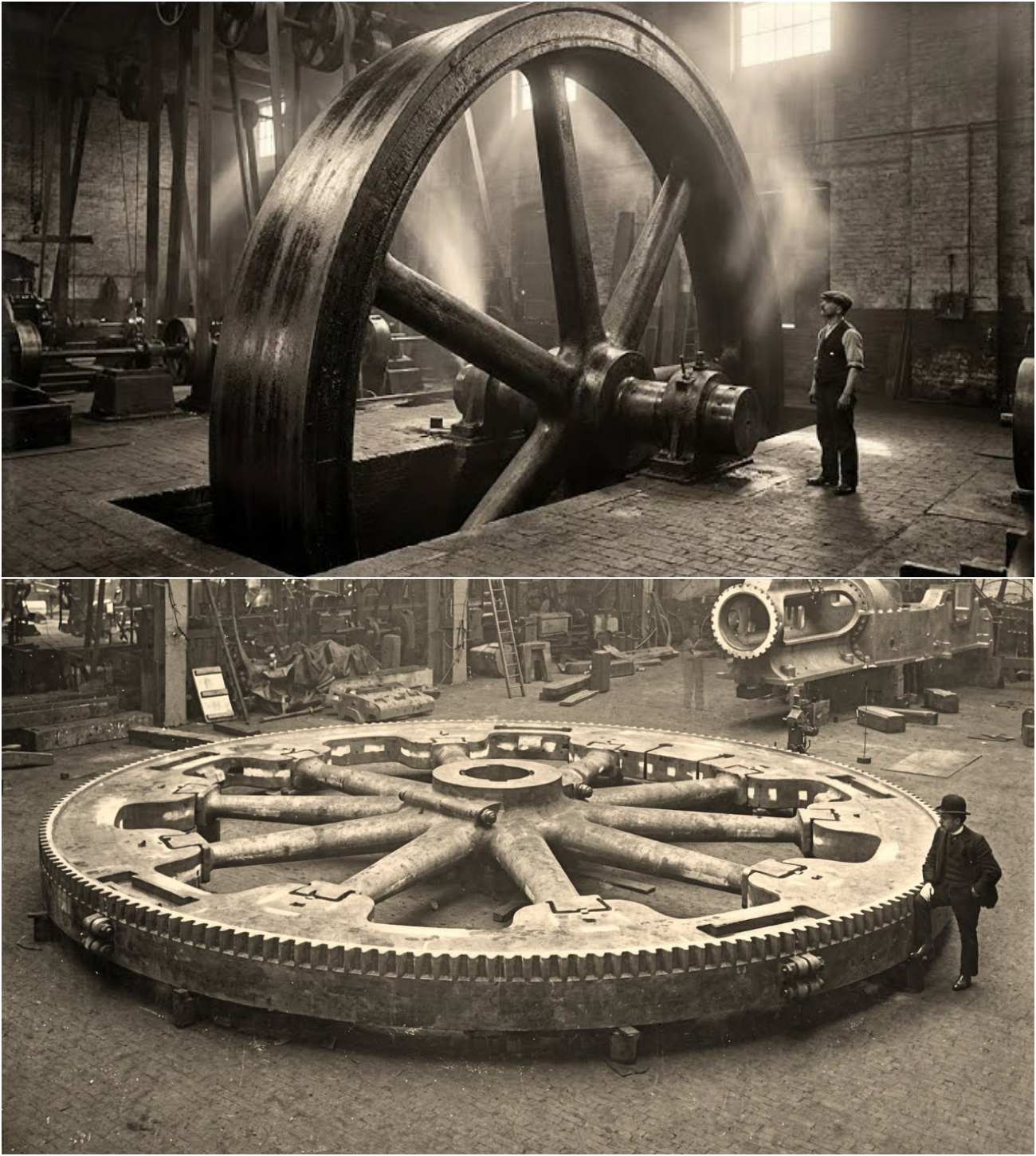

Flywheels solved this problem by storing the energy produced during the surges and releasing it during the low points. The larger the flywheel, the smoother the operation. In the biggest factories, flywheels grew to sizes that were unimaginable, with diameters exceeding 25 feet and weights of over 100 tons. These machines weren’t just backups—they were the very backbone of industrial power. One flywheel could power an entire factory, driving looms, presses, pumps, and carding machines all at once.

The Increasing Danger

By the late 1800s, flywheels had grown in size and importance as factories expanded. It was believed that the larger the wheel, the better it could handle the surges in power. In textile and steel mills, these wheels were routinely built to weigh between 20 to 50 tons. The largest could reach over 200 tons, rivaling the size of small ships.

But with size came risk. The immense weight of these wheels meant they stored an enormous amount of energy. At their peak speed—typically around 60 revolutions per minute—the rim of a flywheel could travel faster than a sprinting horse. While to the human eye, the machine appeared calm, the forces it generated were anything but.

Flywheels operated quietly, without the danger signals that other machines exhibited. Unlike steam boilers, which had pressure gauges, flywheels offered no obvious warning of impending danger. The machines seemed harmless, and workers grew accustomed to their presence. But inside the iron, the stored energy was waiting for the wrong moment to escape.

The Imminent Catastrophe

The true danger of flywheels became apparent when a critical failure occurred. A flywheel, spinning at full speed, was under constant tension, with the rim being pulled outward by centrifugal forces. Cast iron, the material most commonly used for flywheels, does not stretch or absorb stress. Instead, it cracks. And once the rim cracked, there was no stopping it. The failure of a flywheel was not a gradual breakdown—it was a violent, instantaneous explosion of energy.

Engineers knew the risks, but they believed that flywheels were safe as long as they were solid enough and rotated slowly enough. The common belief was that, if the flywheel was built thick and slow, it would last for decades. This was the prevailing thought in the industrial world until the catastrophic events of the late 19th century exposed the flaw in this thinking.

In the Amoske disaster, a flywheel shattered unexpectedly, and the fragments of cast iron were hurled through the building with such force that they pierced brick walls and launched iron beams into the surrounding mill. The resulting destruction was not limited to the immediate area. The violence of the explosion spread outward, reaching distant buildings and causing widespread damage. Workers, who had been accustomed to working in proximity to these massive machines, were now at the mercy of forces they could neither see nor understand.

The Growing Number of Failures

The Amoske disaster was far from an isolated incident. Flywheel failures were recorded across North America and Europe, often occurring under similar circumstances in textile mills, steelworks, and power stations. The frequency of these failures—many of which resulted in fatalities—began to raise serious concerns. But despite the mounting evidence, the industry continued to rely on flywheels.

Engineering journals from the 1890s documented multiple flywheel accidents within just a decade. In one case, a flywheel failure in Pennsylvania killed two workers and injured several others when fragments tore through the engine house. In another incident in England, iron sections weighing over half a ton were found hundreds of feet away from the point of origin.

The pattern of destruction was unmistakable. Flywheels, though essential to industrial processes, were not built with safety in mind. Engineers were focused on efficiency and power, not on the catastrophic consequences of failure. Flywheels were designed to store energy, but the very act of storing energy created an inherently dangerous situation.

A Disastrous Chain of Events

When a flywheel failed, the explosion of energy did not happen gradually. The release of tension was instantaneous. Fragments of the flywheel would fly outward at full speed, tearing through the engine room, the walls, and even other parts of the building. In several recorded cases, fragments were found far beyond the factory yard, landing hundreds of feet away from the explosion. In one case, debris was found across a river, striking buildings on the other side.

As the destruction spread, so did the chaos. Factories that relied on these flywheels were rendered useless, not because of a breakdown in the machinery, but because the very foundations of the building had been shattered. Buildings were designed to hold weight, not withstand the explosive release of energy stored in a flywheel. When the energy inside a flywheel was released, the results were catastrophic.

The Shift Toward Safer Solutions

By the late 19th century, engineers began to understand the risks associated with flywheels. The sheer power they stored was no longer a secret, but the industry struggled to find an effective way to mitigate the danger. It was clear that flywheels had outgrown their usefulness, and the cost of maintaining them, both in terms of safety and resources, was becoming increasingly difficult to justify.

As electric motors began to gain prominence, the need for massive flywheels diminished. Unlike flywheels, electric motors distributed power across smaller, safer units, each storing only a fraction of the energy a flywheel would. This shift to electric power not only made factories safer but also more efficient, as electric motors could be maintained individually without risking catastrophic failure.

The Final Death Knell for the Flywheel

By the early 20th century, the rise of electric motors made the giant flywheel system obsolete. Engineers now had a safer, more efficient means of delivering power. The shift was quiet and gradual, but it was decisive. The massive rotating masses that had once been the beating heart of factories were replaced by smaller, more reliable motors that didn’t carry the same risk of violent failure.

The industry had learned a hard lesson: energy stored in motion had to be controlled, and failure could not be ignored. The flywheel era ended not with a single moment of revolution but with a slow recognition that safety, rather than size and power, would define the future of industrial machines.

Today, the flywheel remains a symbol of both industrial ingenuity and the dangers of unchecked progress. The massive machines that once powered factories have been replaced, but their legacy lives on in the stories of the workers who risked their lives in the name of progress, and in the hard lessons learned about the importance of safety in engineering.