They Laughed At His Scope Mod — Until He Sniped A Target From A Mile Away

The Legacy of Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock: Turning a Flaw into a Weapon

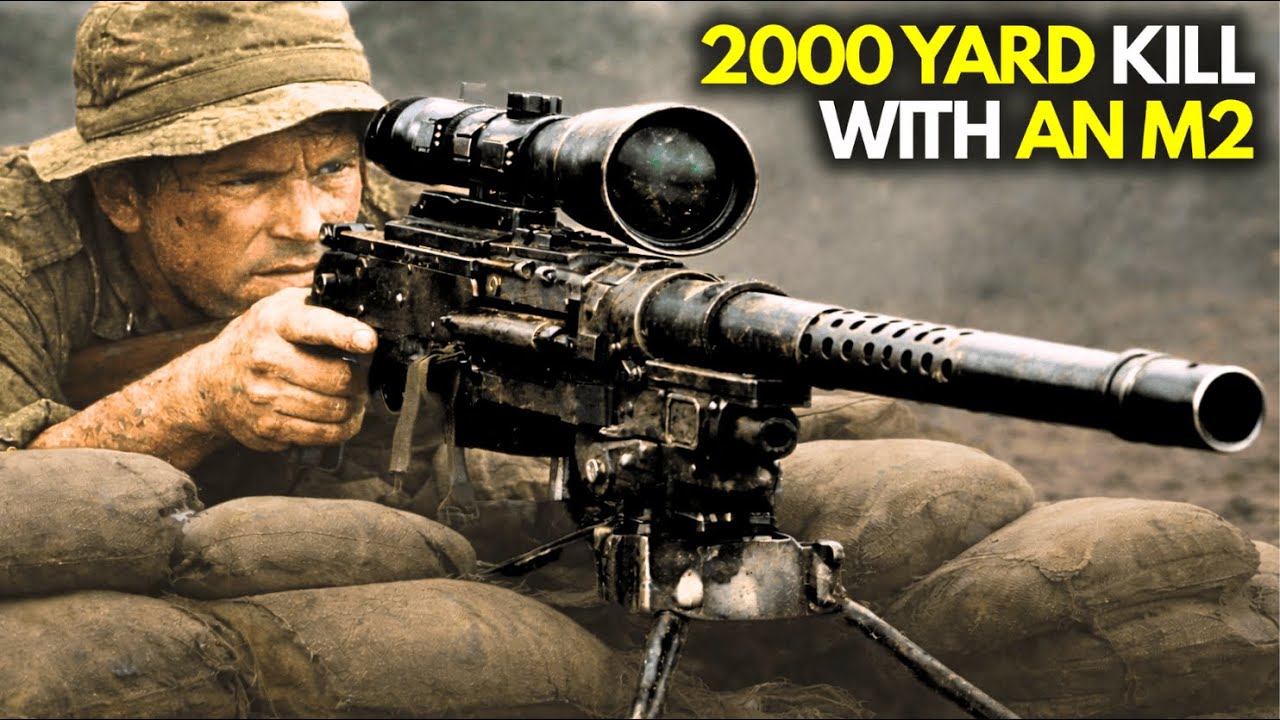

At 7:15 a.m. on February 8th, 1967, Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock crouched in a sandbag bunker on top of Hill 55, watching a man walk across a rice paddy 2,000 yards away. The air was thick with humidity, smelling of burning diesel and wet rot. Through his standard binoculars, the man appeared as a tiny dark speck moving against the green wall of the jungle. But Hathcock knew exactly what he was looking at: a Viet Cong courier pushing a bicycle heavily loaded with crates of ammunition, moving supplies down the Ho Chi Minh trail to kill Marines.

He wasn’t hiding because he knew something that drove Hathcock absolutely crazy—he knew he was safe. To understand the rage boiling inside the man they called “White Feather,” you have to grasp the math of the Vietnam War in 1967. The jungle was a claustrophobic nightmare where most fights happened at 20 yards, but the valleys were massive. The Marines stuck on the hilltops could see for miles, watching the enemy move troops, drag artillery, and set up ambushes. But seeing them and killing them were two different things.

The standard American sniper rifle at the time was the M40, a bolt-action Remington that fired a .308 or 7.62 round. It was accurate and reliable, but it hit a wall at about 800 yards. Beyond that range, the laws of physics took over. The bullet would slow down, lose energy, and start to drop like a stone. The wind would push it five or six feet to the side. At 1,000 yards, hitting a moving man with a standard rifle was like trying to throw a baseball through a tire swing from the outfield—it was mostly luck.

The Viet Cong knew this. They had learned the exact range of the American guns and positioned their camps, supply lines, and command posts exactly 100 yards outside that death zone. They stood there smoking cigarettes, waving at the Marines on the hilltops, mocking them. They knew the Americans couldn’t touch them without calling in an air strike, which took 20 minutes and cost thousands of dollars. Hathcock sat there, gripping his binoculars until his knuckles turned white.

The Decision to Engage

At approximately 0840 local time, his scan pattern caught movement against the mountain backdrop to the north. A twin-engine aircraft emerged from a valley mouth, climbing slowly toward cruising altitude. Its distinctive greenhouse nose marked it as a Mitsubishi Ki-57 transport or possibly a Ki-21 bomber pressed into VIP service. Surrounding it were 11 single-engine fighters, their fixed landing gear and radial engine cowlings identifying them as Ki-43 Hayabusas, the aircraft American pilots called “Oscars.”

Shomo’s fuel state showed adequate reserves for the planned mission profile, but combat maneuvering consumed fuel at three to four times the cruise rate. His ammunition load was full: 1,800 rounds of .50 caliber distributed across six wing-mounted M2 Browning machine guns. His aircraft carried no bombs, no rockets—just bullets and fuel and the Packard-built Merlin engine turning at 2,800 revolutions per minute.

The Japanese formation had not yet detected the two American fighters. They flew in a loose defensive arrangement, the transport at the center, the escorts layered above and below in a pattern designed more for visibility than for rapid response. Their altitude was slightly below Shomo’s, perhaps a thousand feet beneath his current position.

This was the moment where doctrine became personal. The reconnaissance mission had already succeeded. The patrol had located a significant enemy formation operating in daylight over contested airspace. The appropriate action was to mark the position, note the heading, and radio the contact report back to Lingayen for potential interception by a properly sized fighter element. But two P-51s against 13 aircraft was not a proper response.

Shomo understood the parameters. He had flown enough missions to know that the men who survived this war recognized the difference between opportunity and trap. But the P-51D possessed advantages that transcended numerical inferiority. It was faster than the Ki-43 at nearly every altitude. Its dive performance exceeded anything the Japanese fighter could match. Its six .50 caliber guns threw more weight of fire than the twin machine guns or single 20 mm cannon that armed the Oscar.

The First Strike

The first pass was essentially free. The question was whether a single pass could justify the risk of what came after. Shomo’s thumb moved to the gun switch. He pushed the throttle forward, the Merlin’s note changing deeper, more urgent. The P-51’s nose dropped slightly as he converted altitude into speed, trading the energy stored in height for the kinetic energy that would carry him into the enemy formation.

At 600 yards, Shomo’s gun sight tracked toward the transport. He squeezed the trigger. The .50 caliber Brownings erupted simultaneously, their combined rate of fire producing a sustained roar that filled the cockpit with vibration and sound. Tracer rounds converged on the target, and the transport pilot initiated an evasive maneuver too late. Fire engulfed the port wing, and the aircraft banked left, attempting to dive away from the attack, but the damage was catastrophic.

Shomo pulled up and right, breaking off the attack before collision became a risk. The transport was finished, and fire engulfed it as it crashed into the mountains below. But the engagement had just begun. Eleven fighters remained, and they had witnessed the destruction of their principal.

Shomo completed his climbing turn and reversed, diving back toward the formation from a direction the climbing Japanese fighters could not easily counter. A Ki-43 that had separated from the main group crossed his gun sight at approximately 400 yards. Shomo fired a burst of approximately 200 rounds. The fighter rolled inverted, smoke pouring from the radial engine, and began a steep descent that indicated total loss of control.

The Chaos of Combat

The lead Japanese fighter had witnessed his wingman’s destruction and abandoned its attack run on Lipkcom. Shomo pulled up from the valley, climbing to regain altitude and situational awareness. His fuel state had become critical for extended combat. Consumption at combat power had reduced reserves to the point where return to friendly territory required immediate consideration.

Lipscom’s aircraft appeared to port, climbing on a parallel track. The wingman had engaged targets during Shomo’s maneuvering. Subsequent analysis would credit him with three destroyed, but his aircraft showed no visible damage. The Japanese formation’s coherence had collapsed entirely. Individual fighters fled the engagement area on divergent headings.

Shomo broke off the engagement, turning toward the southeast toward friendly airspace, toward the airfield at Lingayen, where fuel and ammunition and ground crews waited. Behind him, the mountains of northern Luzon held the wreckage of a mission that would never complete. The flight home took approximately 40 minutes. During that time, the full scope of what had occurred began to resolve into a tactical after-action narrative that would reach Fifth Air Force headquarters before nightfall.

One American pilot, seven enemy aircraft destroyed in a single engagement. His wingman accounted for three more. The transport and its unknown cargo had been eliminated. The heavy escort that had protected it had ceased to exist as a fighting force. The engagement would eventually be characterized with a single phrase that captured its essential nature: he kept attacking.

The Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor citation for Major William A. Shomo reads with the procedural restraint of official military documentation. It references the date, location, and approximate engagement circumstances. It notes the numerical disparity between the two American aircraft and the 13-ship Japanese formation. It describes Shomo’s decision to attack despite the odds and credits him with destroying seven enemy aircraft in a single engagement while his wingman accounted for three additional kills.

The language is precise, but the emotion is absent. This is the nature of official recognition. The citation exists as a record, not as a narrative. It confirms that certain actions occurred, that those actions met the criteria for the nation’s highest military honor, and that the individual named demonstrated extraordinary valor beyond the call of duty.

What the citation cannot capture is the texture of the experience: the vibration of the airframe under sustained fire, the tunnel vision that accompanied high-G maneuvering, the sweat that accumulated in flight gloves despite the cold of altitude, and the particular clarity of thought that emerged when survival became a problem measured in seconds rather than hours.

Shomo never provided extensive public commentary on the engagement. After the war, he returned to Pennsylvania to the landscapes and communities that had shaped his early life. He pursued a career in aviation that extended his connection to flight without requiring him to engage in combat. He married, raised children, and participated in the ordinary rituals of post-war American life.

His name appeared occasionally in retrospective accounts of Pacific air combat. Veterans’ organizations recognized his achievement. Aviation historians included his engagement in analyses of Mustang operations against Japanese forces, but Shomo himself remained largely silent about the specifics of what had occurred above Luzon.

The Lasting Impact

The Medal of Honor citation for William A. Shomo describes an engagement that lasted approximately two minutes. In that time, he destroyed seven enemy aircraft and contributed to the destruction of three others by his wingman. The official record characterizes this as extraordinary heroism in aerial combat. The pilot who climbed out of that P-51D Mustang at Lingayen airfield knew only that he had survived a situation that should have killed him.

He had attacked when doctrine said to evade, continued when mathematics said to stop, and pressed his advantage until the formation that outnumbered him ceased to exist as a fighting force. The mountains of Luzon kept the wreckage of that January morning. The pilot who created that wreckage lived into peacetime, into a life measured by quieter achievements than the destruction of enemy aircraft.

The legacy of Major William A. Shomo is a testament to the calculated audacity that defines true heroism in combat. His story reminds us that courage is not merely the absence of fear but the presence of resolve in the face of overwhelming odds. In the skies above Luzon, one man proved that the mathematics of survival could be rewritten, and in doing so, he changed the course of aerial combat forever.

The impact of Shomo’s actions extended beyond that day in January. His engagement became a case study for future pilots, demonstrating the importance of surprise, speed, and the ability to adapt in combat. The lessons learned from his bravery would influence tactics and strategies in subsequent conflicts, ensuring that his legacy lived on in the annals of military history.

In conclusion, Major William A. Shomo’s extraordinary actions on that fateful day serve as a powerful reminder of the courage and ingenuity of those who serve in the armed forces. His ability to defy the odds and take decisive action in the face of danger exemplifies the spirit of the American soldier and the relentless pursuit of victory against all odds.