China Challenged US Helicopter — Big Mistake

The 72-Minute Mistake Over the South China Sea

At 2:30 p.m. local time, a U.S. Navy helicopter hung over the South China Sea doing something that looks boring until you understand what it means.

It wasn’t racing toward a coastline. It wasn’t firing. It wasn’t even “showing the flag” in the Hollywood sense. It was simply staying put—slow, methodical, patient—like a fisherman who already knows where the fish will surface.

Somewhere below, a diesel-electric submarine was running out of choices.

Diesel boats have a problem nuclear submarines don’t: they can’t stay down forever without paying a price. Batteries drain. Air grows stale. Eventually the submarine has to rise closer to the surface—sometimes to snorkel, sometimes to recharge—because the laws of physics don’t care about national pride.

And when a submarine is forced upward, the ocean becomes less of a hiding place and more of a stage.

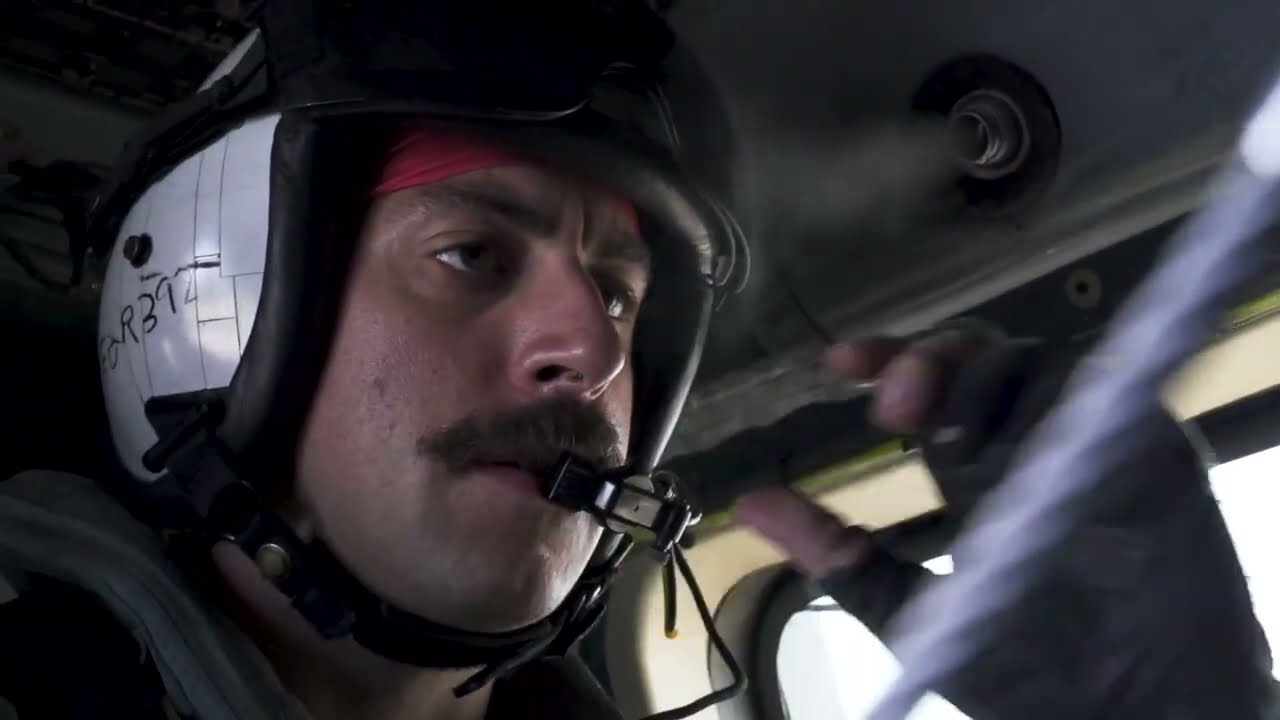

Above it, the U.S. Navy’s MH‑60R “Romeo”—an anti-submarine warfare workhorse—was doing the kind of “quiet” work that decides entire wars long before the first shot. The crew weren’t looking for a fight. They were looking for certainty: a track, a signature, a pattern.

That’s when Beijing decided to make it stop.

A Chinese attack helicopter—often referenced in defense circles as the Z‑10—was scrambled with a mission that sounded simple in a briefing room:

Go intimidate the Americans.

Make them leave.

Protect the submarine.

What happened instead was far more dangerous, not because it created a battlefield incident, but because it created a data incident—the kind of mistake you can’t apologize away.

For the next 72 minutes, one pilot tried to look threatening.

And accidentally taught the U.S. Navy exactly how to beat him.

The first warning: a threat spoken into the wrong airspace

The Chinese helicopter came in hard and fast, cutting across the Romeo’s nose at roughly 500 meters. Close enough to be felt. Close enough to make a point. Close enough that, if someone misjudged closure rates or wake turbulence, metal could meet metal.

Then the radio call came—stern, official, rehearsed:

“Foreign military aircraft. You are approaching Chinese territorial waters. Alter your course immediately.”

It was a classic move: declare authority, force a decision, create a narrative.

There was just one problem.

They weren’t near Chinese territorial waters. Reports like this typically place these encounters dozens of nautical miles from land, in international airspace—the legal grey-blue that everyone argues about and nobody “owns.”

The Romeo’s crew didn’t flinch. Not because they were fearless. Because they were prepared.

They knew something the Chinese pilot either didn’t know, or couldn’t admit to himself in the moment:

He wasn’t confronting a lone helicopter.

He was confronting a network.

And the closer he got, the more he would feed that network.

The helicopter that doesn’t just fly—it listens

From the outside, the MH‑60R looks like a sensible machine: rotor, tail boom, sensors, antennas, hardpoints. A utilitarian aircraft meant to do unglamorous work in bad weather and worse politics.

But some of those “bumps and bulges” aren’t just equipment.

They’re collectors.

Modern naval helicopters carry suites designed to do what electronic warfare people describe in simple terms: find, classify, and remember. They vacuum up emissions—radar pulses, datalink bursts, voice traffic, weird electronic fingerprints that most people never think of as a “signature,” but which can be as unique as a human voice.

To a pilot trying to intimidate, it feels like a contest of nerve.

To an electronic support measures operator, it can feel like Christmas morning.

Because intimidation requires communication. Communication requires emissions. Emissions can be logged.

And a logged emission becomes a future vulnerability.

The Chinese pilot didn’t fire. Not at first. He didn’t have to. His job was theater: close passes, aggressive angles, flares—gestures designed to say you’re not welcome here without crossing the line into an act of war.

So he began to perform.

The flares: bright, loud, and strategically useless

Two flares spat into the air near the Romeo—an unmistakable flare of fire meant for human eyes. It wasn’t a strike; it was a statement.

But statements don’t change sonar contact.

Below the surface, the submarine was still being tracked. And when the Chinese helicopter tried to disrupt the situation overhead, it created the opposite effect underwater: pressure.

Submarines don’t like pressure. Pressure makes captains do things they shouldn’t.

A diesel submarine that realizes it’s being held in place—tracked, cataloged, “played with”—may choose to crash dive, turn sharply, change depth quickly.

And those moves make noise.

In submarine warfare, noise is confession.

A rushed dive can create cavitation, mechanical strain, and transient sounds that radiate outward like a flare fired underwater. In the right conditions, those noises can be picked up by multiple sensors—sometimes not just by the helicopter, but by other assets in the area.

The Chinese pilot’s attempt to protect his submarine risked forcing it to betray itself.

If this were an actual shooting war, that kind of betrayal could be fatal.

But the most severe damage wasn’t to the submarine’s stealth.

It was to the helicopter pilot’s electronic secrecy.

The “lock” that should never have happened

After nearly twenty minutes of posturing, the Chinese pilot tried to escalate within the boundaries of “not firing.”

He sought a radar lock.

In the cockpit, a lock is seductive. It’s the moment the aircraft stops being a camera and becomes a weapon. The tone changes. The symbology tightens. The world feels simpler: there is a target, there is a solution.

For a few seconds, it probably felt like control.

Then the Americans flipped the script.

Not with a missile.

With electromagnetic force.

A U.S. Navy EA‑18G Growler—the kind of aircraft that exists specifically to ruin your day without ever touching you—lit up the battlespace with jamming.

And the Chinese pilot’s radar didn’t merely lose the lock.

It started lying.

On his display, the Romeo didn’t just “disappear.” It multiplied. Contacts split and smeared. Ghost returns bloomed. The target seemed to shift in impossible ways—too fast, too inconsistent, too wrong to trust.

Jamming, at its highest level, isn’t simply noise. It’s manipulation: forcing the enemy’s sensors to misinterpret reality until the pilot can’t tell what’s true.

It’s the electronic version of stepping into a dark room and realizing your eyes have been replaced with a broken screen.

Meanwhile, the Romeo’s crew remained calm—because calm is easy when you know your side owns the invisible dimension of the fight.

The carrier strike group “looks” at you

Then came the moment that changes a pilot’s posture from aggressive to careful.

The broader U.S. force—often described as a carrier strike group in these scenarios—began to illuminate the area with more capable sensors. Not necessarily because it needed to, but because it wanted to be unmistakable.

It’s one thing to bully a helicopter.

It’s another to be reminded that the helicopter is merely the fingertip of an entire hand.

Somewhere beyond the horizon, jets could launch—not to fire, but to arrive. To be seen. To make the message physical:

You are not intimidating a lone aircraft.

You are auditioning in front of an empire of sensors.

The Chinese pilot tried to adapt. He switched frequencies. He increased power. He cycled systems—an instinct as old as machines: turn it off, turn it on, hope the world behaves.

But the world didn’t behave.

Because the American system wasn’t reacting. It was orchestrating.

The closer he got, the more he gave away

Frustrated, the Chinese pilot closed again—still around that 500-meter range, close enough to read details off the airframe.

This is the part nobody tells you about intimidation flights: proximity feels powerful, but it can be catastrophically expensive.

Because at close range, modern sensors don’t just “see.” They measure.

Missile warning systems can track movement patterns.

Infrared cameras can record thermal hotspots—engine exhaust, transmission housings, heat blooms under high power.

Electronic collectors can log every attempt to reacquire radar lock, every pulse pattern, every frequency hop.

Even if you never fire a weapon, you are teaching the other side what you look like, how you move, and how you struggle.

In effect, you are handing them a future playbook.

And the pilot—perhaps thinking aggression would compensate for electronic failure—began to throw the helicopter around: sharp turns, lunges, pitching moves meant to force the Romeo into discomfort.

But helicopters have limits. Aggression costs airspeed. It costs control margin. It costs temperature and hydraulic pressure. It’s not free.

The more he maneuvered, the more his aircraft heated up. The more his systems worked, the more they emitted. The more he tried, the more the Americans learned.

Some accounts describe multiple lock attempts—over and over—as if persistence could burn through the jam.

From an intelligence perspective, that’s a gift.

It’s like watching someone repeatedly enter passwords while you write them down.

The final humiliation: nothing changes

By 3:42 p.m., after 72 minutes, the submarine was still being tracked.

The Romeo hadn’t moved.

The Americans hadn’t backed off.

The intimidation hadn’t worked.

And now the Chinese pilot faced the one thing that can feel worse than losing a fight:

Reporting failure.

Because ground control could likely see the same picture he could. They could see he hadn’t displaced the American helicopter by a single mile. They could see the American presence was steady, professional, confident.

And worst of all—if this encounter happened the way it’s often described in dramatic retellings—Beijing would have to live with the possibility that the real loss wasn’t face.

It was exposure.

Seventy-two minutes of emissions.

Seventy-two minutes of signatures.

Seventy-two minutes of recorded behavior.

A single encounter that might help the U.S. understand not just one pilot, but a whole slice of a system: how the aircraft searches, how it locks, how it talks, how it reacts when jammed, how it strains when pushed.

In modern warfare, that’s not an embarrassment.

That’s damage.

Because missiles don’t just chase heat. They chase predictability.

Jammers don’t just disrupt signals. They exploit patterns.

And the surest way to lose a future fight is to show your enemy—up close, in high definition—exactly how you operate.

The Chinese pilot came to scare an American helicopter away.

Instead, he may have done something far more consequential:

He turned intimidation into intelligence—

and taught the U.S. Navy something Beijing never wanted them to know.