I. The Night Before Harlem Changed

The last night Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson walked Lenox Avenue, Harlem felt restless.

Streetlights flickered in damp halos. The El rumbled overhead like distant thunder. Dice clicked in alleyways; jazz seeped from half‑open doors. And everywhere, there were whispers:

“Bumpy ain’t lookin’ too good, man.”

“He’s been sick.”

“No, that’s just age. Kingpin don’t retire, he just walks slower.”

Bumpy moved with his usual measured stride, cane tapping the sidewalk, hat tilted just so. But his breath came shorter than it used to, and his heart hammered a little harder on the inclines.

At his side, his driver and longtime lieutenant, Junie Byrd, watched him with quiet worry.

“You should be home, Bump,” Junie murmured. “Doc told you to rest. You ain’t gotta be out here every night no more. Harlem know who you are.”

“That’s exactly why I gotta be out here,” Bumpy replied, eyes scanning the block. “They know who I am, but some of ’em forgot what that means. A man stops walking his own streets, the streets start walkin’ without him. That’s when things get stupid.”

He stopped in front of a small, nondescript brownstone. No neon. No music. Just a stoop and a door like a hundred others.

“You sure about this?” Junie asked.

Bumpy’s lips curled in a faint smile.

“Ain’t about me bein’ sure,” he said. “It’s about him bein’ ready.”

“Him” was a name already buzzing in certain corners of Harlem: Leroy “Nicky” Barnes.

Young. Ambitious. Stylish. A man who smelled opportunity like other men smelled trouble—and sometimes mistook one for the other.

Bumpy climbed the stoop, each step measured. Inside his coat pocket, folded twice, was a letter he’d written by hand—a rare thing. His handwriting was neat, precise, disciplined like the man himself.

He wasn’t delivering it tonight. That wasn’t how this was going to work.

Some lessons, he knew, only made sense when the walls closed in.

II. The Letter That Went Nowhere—At First

A week later, in a kitchen that smelled faintly of collard greens and cigarette smoke, Bumpy slipped the letter into an envelope and sealed it with a slow press of his thumb.

His wife, Mayme, watched him from across the table, arms folded.

“You don’t write letters,” she said. “You give orders. You have conversations. You don’t write.”

“This ain’t orders,” Bumpy replied. “Orders get forgotten as soon as the money change hands. This is… somethin’ else.”

“Advice?” she asked.

He smirked.

“Warning,” he said. “Wrapped up pretty so he might actually open it.”

“And you’re really leaving it to him?” Mayme asked. “That boy don’t listen to nobody. He thinks a suit and a Cadillac make him smart.”

“Cadillacs don’t make a man smart,” Bumpy said calmly. “They just make it easier for him to get to the wrong place faster.”

He wrote one more thing on the front of the envelope, in a careful, steady script:

FOR NICKY BARNES — TO BE OPENED WHEN HE CAN’T RUN NO MORE

He handed it to Junie.

“Not now,” Bumpy said. “You don’t give this to him unless two things happen: one, I’m gone. Two, he’s locked down and outta moves. You hear me, Junie? Not before.”

Junie frowned.

“You really think it gonna get that far?” he asked.

Bumpy’s eyes were tired, but clear.

“You and me both know where that boy’s headed,” he said. “Question ain’t if. It’s how hard he hits the wall. Maybe this slows it down. Maybe it don’t. But a man should at least be warned before the roof falls in.”

Junie slid the envelope into the inside pocket of his jacket, like it was something fragile and dangerous at once.

“You trust him with your name?” he asked. “That’s a lotta weight to hand a young man who thinks bein’ untouchable is a plan.”

“I ain’t handing him my name,” Bumpy said. “I’m handin’ him a mirror. Whether he looks in it? That’s on him.”

III. The Funeral and the Future

When Bumpy Johnson died in 1968—collapsing in a Harlem restaurant, his head hitting the table softly as if he’d just fallen asleep—Harlem came out into the streets.

Old ladies in church hats. Numbers runners. Hustlers. Business owners. Kids who’d only heard stories. Cops who’d spent careers trying to pin something big on him. Preachers who’d prayed for his soul and begrudgingly appreciated his donations.

And, standing on the edge of the crowd in a dark suit and sunglasses, Leroy “Nicky” Barnes.

He hadn’t known Bumpy well. They’d had a few tense conversations. Bumpy had warned him once, flat‑out:

“You fast,” he’d said. “Too fast. You think if you run fast enough, the law of gravity ain’t gonna apply to you. Newsflash: the ground always wins.”

At the time, Nicky had smiled politely and filed it away under Old Man Advice—the kind of thing you nodded at and ignored.

But as he watched the casket go by, he couldn’t help feeling something like a shift.

The old guard was leaving. Harlem’s shadow government, the quiet arrangement between crime, community, and cops, was cracking. Where there was a vacuum, something would rush in.

Nicky intended to be that something.

Years rolled forward. Heroin flooded streets. Money changed hands, changed lives, changed loyalties. Nicky Barnes went from a name to Mr. Untouchable—the press gave him the title, but he believed it.

Three-piece suits. Silk ties. Custom shoes. Newspapers printed his face; he collected them like trophies.

He beat cases. He walked out of courtrooms smiling. He became the embodiment of swagger in a city teetering on the edge.

Somewhere in Harlem, in the back of a closet, Junie still had the envelope.

Every so often, he’d take it out, look at Bumpy’s handwriting, and then tuck it back. The time, he knew, wasn’t right.

Not yet.

IV. The Fall

In 1977, the New York Times ran a cover story on Nicky Barnes.

MR. UNTOUCHABLE, the headline practically shouted. A defiant photo stared back at law enforcement and politicians: Barnes in a sharp suit, eyes hard, chin tilted up.

They took it personally.

What followed wasn’t immediate. The federal government doesn’t move fast; it moves relentlessly. Phones were tapped. Informants flipped. Surveillance piled up like snowdrifts.

And then, one morning, everything cracked.

Raid. Shackles. Courtrooms. Long sentences.

In 1978, Nicky Barnes was convicted on conspiracy to distribute heroin and other charges. The judge gave him life without parole.

Untouchable had found something that could touch him after all: the United States government’s patience running out.

In the chaos that followed, as his empire splintered and his so‑called friends scrambled for cover, an old man in Harlem ironed a shirt, brushed off his best jacket, and took a slow subway ride downtown.

Junie Byrd walked through the heavy doors of a federal detention center with an envelope in his inside pocket. The guards looked him up and down, checked his ID, checked his name.

“Who you here to see?” one asked.

“Leroy Barnes,” Junie said. “Call him Nicky. Tell him… tell him an old friend of Bumpy’s got somethin’ for him.”

V. The Envelope on the Table

Prison visiting rooms have a particular smell: disinfectant, institutional coffee, old fears trying to pretend they’re not afraid anymore.

Nicky sat at a metal table, jumpsuit crisp, posture tight. He hadn’t fully accepted this new reality yet. Part of him still expected a lawyer to burst in with a technicality, a deal, a loophole.

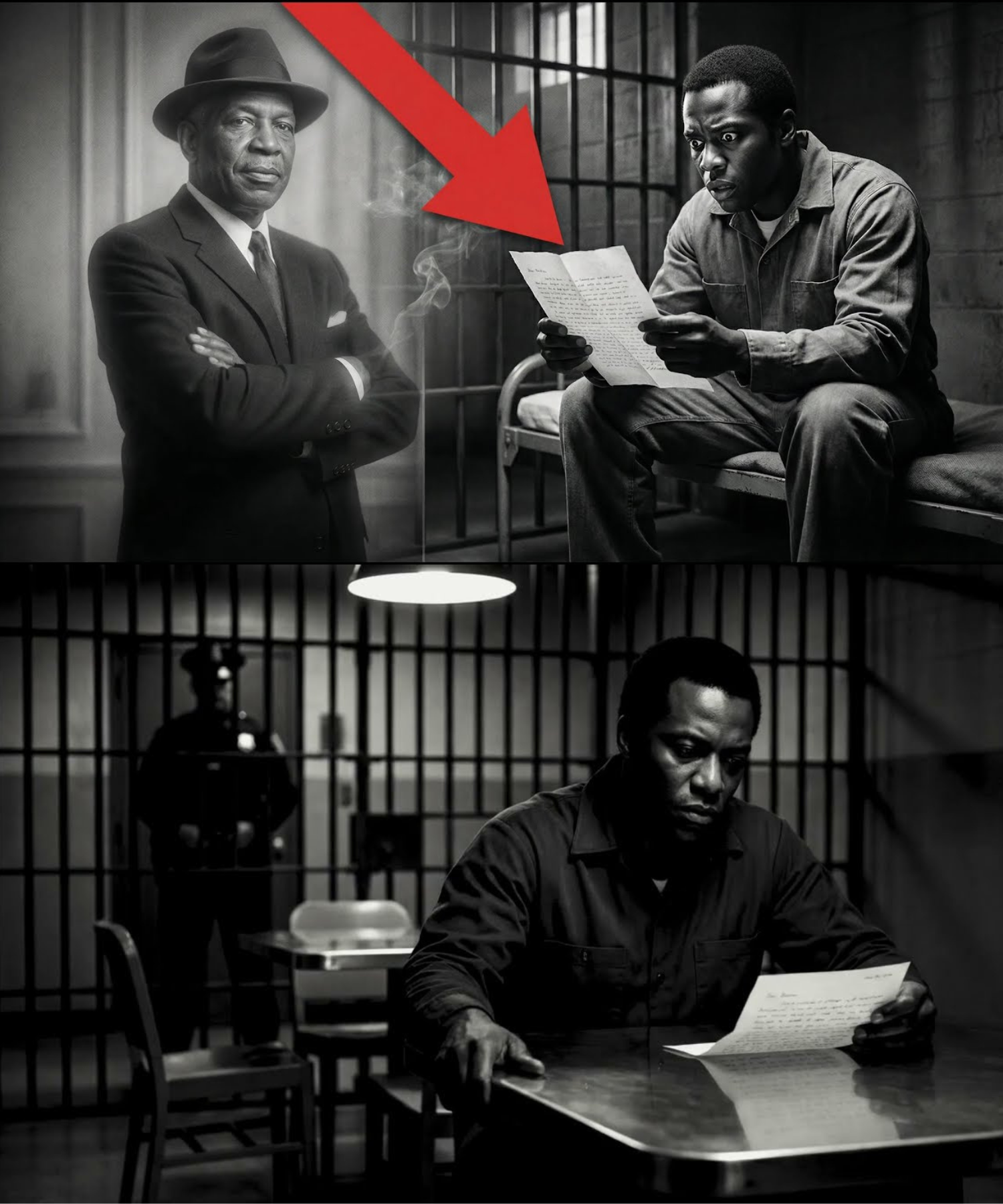

Instead, an old man with a Harlem gait and tired eyes sat down across from him and slid an envelope across the scarred tabletop.

“What’s this?” Nicky asked, suspicion automatic.

Junie placed one weathered hand gently on the envelope.

“From Bumpy,” he said.

The name hung there. For a second, Nicky almost laughed.

“Bumpy?” he said. “Man, Bumpy been dead ten years.”

“Letter’s older than that,” Junie replied. “He wrote it before he went. Told me hang onto it. Said, ‘Don’t give it to him ’til he can’t run no more.’”

Something flickered behind Nicky’s eyes.

“I can still appeal,” Nicky said quickly. “This ain’t over.”

Junie studied him, then nodded at the guards lining the walls.

“You sittin’ in a jumpsuit with a number on your chest, talkin’ behind glass to your kids, if they even bring ’em,” Junie said quietly. “Sounds pretty ‘over’ to me.”

He pushed the envelope closer.

“You can throw it away. You can read it. Only two options Bumpy left you with.”

Nicky stared at his own name in that careful, old‑fashioned script:

FOR NICKY BARNES — TO BE OPENED WHEN HE CAN’T RUN NO MORE

His throat went dry in a way that had nothing to do with the stale air.

He picked it up.

“Why’d he even…?” Nicky began, then stopped himself. “You gonna watch me read this?”

Junie shook his head and slowly stood.

“I saw him write it,” he said. “I don’t need to see you read it. That part’s between you and the man you lookin’ at in the mirror every mornin’.”

He placed his palm flat on the table for a second, an old‑world sign of respect, then walked away.

Nicky was left with the envelope and the sudden, unnerving feeling that the past had just pulled a chair up to his table.

VI. The Letter

Nicky opened it with fingers that were steadier than he felt.

The paper inside was thick, off‑white, the ink just slightly faded at the edges. Bumpy’s handwriting marched across it in clean, controlled lines.

Nicky began to read.

Nicky,

If you got this in your hands, then the day I saw coming finally caught up to you.

You probably sittin’ somewhere you can’t leave when you feel like it. If you’re lucky, you got time. If you’re unlucky, you got nothin’ but time.

Either way, you gonna read this all the way through, because a man in your position don’t have the luxury of thinkin’ he knows everything anymore.

You and me, we ain’t friends. We ain’t enemies either. We two men who walked some of the same streets and made some of the same bad bargains with the same devil—power, money, respect. Difference is, I made mine in a time when my people had fewer options, and I tried, best I could, to stand between Harlem and the worst of what could happen to her.

You? You wanted to stand above Harlem. That’s where your trouble started.

I watched you from a distance. Sharp suits, sharper tongue, always smilin’ like you had an inside joke with yourself. They called you Mr. Untouchable. You let ’em. That title feel good, don’t it?

Feels like armor. Feels like a crown. Feels like they finally see you the way you always wanted to be seen.

Here’s the thing nobody told you about bein’ “untouchable,” so I will:

There is no such thing.

There are only men the system ain’t got round to yet.

You thought the game was about outsmartin’ cops and judges. That ain’t the real game. The real game is this:

Can you take power without lettin’ it turn you into the same monster that once had his boot on your neck?

I heard the stories. You ran dope like it was a business school project. You organized. You delegated. You made sure the product was pure and the money was laundered. Your books probably looked better than some legit companies.

Everybody likes to call that “genius.”

Lemme tell you what real genius would’ve been:

Usin’ that same brain to build somethin’ that wouldn’t put your own people in the ground or in the cages you sittin’ in now.

You think I don’t know the temptation? Boy, I practically invented some of the routes you walked on. I kept certain things out of Harlem for years not because I was a saint, but because I knew what would happen if they came in.

You brought ’em in anyway. You called it opportunity. You called it “gettin’ ours while we can.”

But every kilo you moved was a funeral somebody had to plan or a mother’s prayer that never got answered.

You probably justify it by sayin’ if you didn’t do it, somebody else would.

That’s the oldest lie in the world. That’s how cowards sleep at night.

I ain’t writin’ this to condemn you. The judge already did that. The papers did that. One day, some white folks on TV will probably make movies about you and turn you into a myth, ’cause that’s what they do when they don’t have to deal with the real body count no more.

I’m writin’ this because I know what it is to sit in a small cell and have to face the man only you know you really are.

I did time. I sat on that bunk and thought about how many kids would’ve had a different life if I’d made different choices. I thought about the ways I tried to shield Harlem and the ways I failed her anyway.

Here’s what you need to understand, Nicky, and it ain’t gonna feel good:

You ain’t sittin’ in that cell just because the feds targeted you.

You sittin’ there because on some level, you thought you were smarter than the cost.

You thought you could ride the tiger and not get bit. You thought the rules that pull every other man down somehow didn’t have your name on ’em.

Now you know better.

So the question ain’t “Why me?” No use askin’ that. The question is:

What are you gonna do with the truth now that it ain’t a rumor anymore?

Maybe you think the only move you got left is to keep your mouth shut and die in there with some legend intact. Maybe you think about talkin’ to the feds, tradin’ names for years. Maybe you just try to forget who you were on the outside so you don’t go crazy on the inside.

I can’t tell you which road to take. All them roads got a toll booth.

But I’ll tell you this:

Who you really are is not the man in the headlines. Not the “untouchable” fool on the magazine cover smilin’ like he just beat the world.

Who you are is the man who sits alone after lights‑out, rememberin’ the faces of the people he hurt and the people he helped and weighin’ which side is heavier.

You think you understand the streets? You don’t understand nothin’ until you understand this:

Power without responsibility is just another kind of slavery. You got chained to your own ego, and the system just came along to tighten the lock.

If you want to be free—even in a place without freedom—start here:

Tell yourself the truth about what you did, who you did it for, and who paid the price.

Don’t lie like you lied in those courtrooms, on those corners, in those bedrooms where you promised girls things you couldn’t deliver. Don’t spin it like you did for the reporters.

Just be honest with the only jury that still matters: you.

If you can do that, then maybe, just maybe, this time you spend behind bars won’t be wasted.

And when some young buck in that yard comes up to you one day, eyes bright, talkin’ about how he wanna be “untouchable” like you once were…?

You look him in the eye and tell him the truth I’m tellin’ you now.

Not to save your reputation.

To save his life.

Because if a man in your position don’t use what he’s learned to stop somebody else from crashin’ into the same wall, then all them years when you thought you were a king are nothing but dust.

You ain’t gotta answer me.

I’ll be long gone when you read this.

But you do gotta answer yourself.

— Bumpy

VII. The Weight of the Words

When Nicky finished the letter, the room felt smaller.

The noise of the visiting area faded into a dull hum. Guards called names. Metal chairs scraped the floor. Somewhere, somebody laughed too loud for a prison.

Nicky didn’t move.

He read the last paragraph again. Then again.

You thought you were smarter than the cost.

He saw flashes: women counting money on kitchen tables, hands white with heroin dust. A neighbor’s boy who’d started running for him, then graduated to using, then stopped coming around altogether.

He saw himself on the Times cover, grinning like he’d beat the system, when all he’d really done was speed up the collapse.

He thought of the men he’d mentored into the game. The ones in cages now. The ones in graves.

For the first time, “life without parole” stopped feeling like an unjust sentence imposed from the outside and started feeling like a reckoning summoned from the inside.

The letter didn’t tell him anything he couldn’t have guessed if he’d really wanted to. It did something worse:

It stripped away the excuses.

Nicky folded the letter slowly along the original creases. His hands, always so sure when handling cash or guns, shook a little.

Across the room, a young inmate watched him. Kid couldn’t have been more than twenty.

He hesitated, then came over.

“Yo,” the kid said, keeping his voice low. “You really Nicky Barnes?”

Nicky looked up, eyes sharper than they’d been in days.

“Used to be,” he said.

The kid shifted, glancing at the guards.

“Man, you a legend,” he said. “Before I got locked up, I used to hear stories. How you beat cases, how you had the whole city on lock. Some of us… we used to say we wanted to be just like you.”

Nicky looked down at his jumpsuit, at the faded numbers stenciled over his heart.

“You still want that?” he asked quietly.

The kid shrugged, half‑defiant, half hopeful.

“I mean, not the prison part,” he said. “But, you know. The power. The respect.”

It was almost exactly the scenario Bumpy had described.

What are you gonna do with the truth now?

Nicky unfolded the letter, smoothed it on the table, and tapped it with one finger.

“You can read?” he asked.

The kid bristled.

“Yeah, I can read,” he said.

“Good,” Nicky replied. “’Cause you about to read something that might save your life.”

He slid the letter across the table.

“Start at the top,” he said. “And don’t skip nothin’.”

VIII. Finally Understanding

Later that night, lights out, Nicky lay on his bunk with his hands behind his head, staring at the underside of the bed above him.

The prison had its own soundtrack now: distant shouting, a guard’s keys jingling, the thump of footsteps on concrete. None of it felt as loud as the quiet realization that had settled into him.

For years, he’d told himself a story:

He was a businessman. A necessary evil. A symbol of Black empowerment in a racist system. A self‑made man who’d risen above poverty using the only tools available to him.

Some of that had truth in it. Most of it was cover.

Bumpy’s letter hadn’t changed the facts of his sentence, hadn’t offered him an escape, hadn’t absolved him.

What it did was worse and better:

It made him see his life from above, like he was looking down at a chessboard he’d once believed he controlled, realizing now how many pieces had never really been his to move.

He finally understood what Bumpy had meant, years ago, about standing between Harlem and the worst of the world versus standing above her and letting the worst seep through as long as it paid well.

He understood that “untouchable” had been a costume he’d worn, not a reality he’d lived. That power without responsibility wasn’t freedom—it was a different kind of chain.

He thought of the kid in the visiting room, eyes bright with the same hunger that had once driven him.

He thought of Bumpy, an old man hunched over a table, taking the time to write a letter to a younger hustler he didn’t even particularly like, because he knew how the story tended to end.

Nicky had always believed his downfall came the day the feds finally got their case lined up.

Lying there, he finally understood:

His downfall had started the day he believed his own myth.

IX. What He Did After

In the years that followed, the world outside kept changing.

Laws shifted. Presidents came and went. The drug trade morphed, new names, new products, same old hunger.

Inside, Nicky Barnes did something nobody who’d known him in his prime would have predicted.

He started talking.

Not the way the newspapers would later describe it—“cooperating witness,” “informant,” the tabloids yelling RAT in bold letters.

Before any of that, he talked to the men in the yard.

To the young ones who’d come in on minor charges and were already planning bigger plays when they got out.

To the older ones who were still clinging to the idea that one more run, one more score, one more corner would finally get them the respect they craved.

He talked about the letter. He didn’t show it to everyone. Only to the ones who looked like they might still have a choice ahead of them.

“You think bein’ feared is the same as bein’ respected,” he’d say. “I used to think that too. Then I realized: the people who feared me either wanted me dead, locked up, or out the way. Ain’t nobody mournin’ you because they scared of you. They just waitin’ for their turn.”

He didn’t romanticize Bumpy. Didn’t turn him into a saint. He told the whole truth:

“How a man like Bumpy tried to hold a line and how he failed in places. How he’d done dirt and regretted some of it. How power and guilt share the same bed.”

He didn’t absolve himself, either.

“I ain’t no hero,” he’d say. “I ain’t even a cautionary tale if you don’t pay attention. I’m just what happens when a man mistakes his reflection for a god.”

The prison rumor mill spun things its own way. Some called him a prophet, others a hypocrite, others a sellout. He didn’t wrestle with the labels as much anymore.

He’d already had the only verdict that mattered.

X. The Legacy of a Piece of Paper

Years down the line, when journalists and documentarians started sniffing around for stories about “the old days,” about Harlem’s legendary gangsters and drug lords, they’d sit across from a graying Nicky Barnes and ask:

“When did it really hit you? When did you finally understand what you’d done, who you were, what it meant?”

And Nicky would sometimes mention the trial, the sentence, the day he realized “life without parole” meant he might die in a cage.

But on the days he was being honest—honest the way Bumpy’s letter had asked him to be—he’d tell a different version:

“An old man left me a letter,” he’d say. “Wrote it years before I was ready to read it. Ten pages, maybe less. Wasn’t nothin’ fancy. Just a man who’d already been where I was goin’ tryin’ to tell me there wasn’t nothin’ at the end of that road but a wall.”

He’d smile, not happily, but not bitterly either.

“I got it too late to save myself,” he’d say. “But not too late to see myself.”

Sometimes he’d add:

“And if you’re smart, you listen to a dead man’s words before you end up livin’ his life.”

No one outside ever got to see the original letter. Some said it was lost. Others whispered that Nicky kept it folded in a Bible, or tucked inside a legal pad, or hidden in the lining of an old folder.

But on certain nights, when the prison was quiet and the world outside felt especially far away, a man in a cell would sit on his bunk, unfold a piece of paper that smelled faintly of Harlem and time, and read it again.

Not because he didn’t remember the words.

Because every time he read them, he understood just a little more.

XI. What He Finally Understood

When Nicky Barnes finished Bumpy Johnson’s letter for the first time in that prison visiting room, he finally understood something the streets had never taught him:

The real measure of a man wasn’t how high he climbed on a crooked ladder—it was how honest he was about the bodies that ladder was built on.

He understood that “untouchable” was just another word for “not yet punished,” and that every choice he’d made had been leading him, step by step, to that metal table and that folded paper.

He understood that Bumpy, for all his sins, had tried to put his weight between Harlem and complete devastation, while Nicky had put his weight on top of Harlem and called it success.

Most of all, he understood that the only power left to him now—the only clean power he would ever have—was to tell the truth loud enough that maybe, somewhere, some kid who thought he wanted to be the next Nicky Barnes would think twice.

And if that happened, just once, in some other neighborhood years down the line?

Then an old man’s letter, delivered late but read in time, would have done more than outlive Bumpy Johnson.

It would have outlived the lie that men like them had to become monsters to matter.