They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

.

.

The Unlikely Marksman: John George’s Fight at Point Cruz

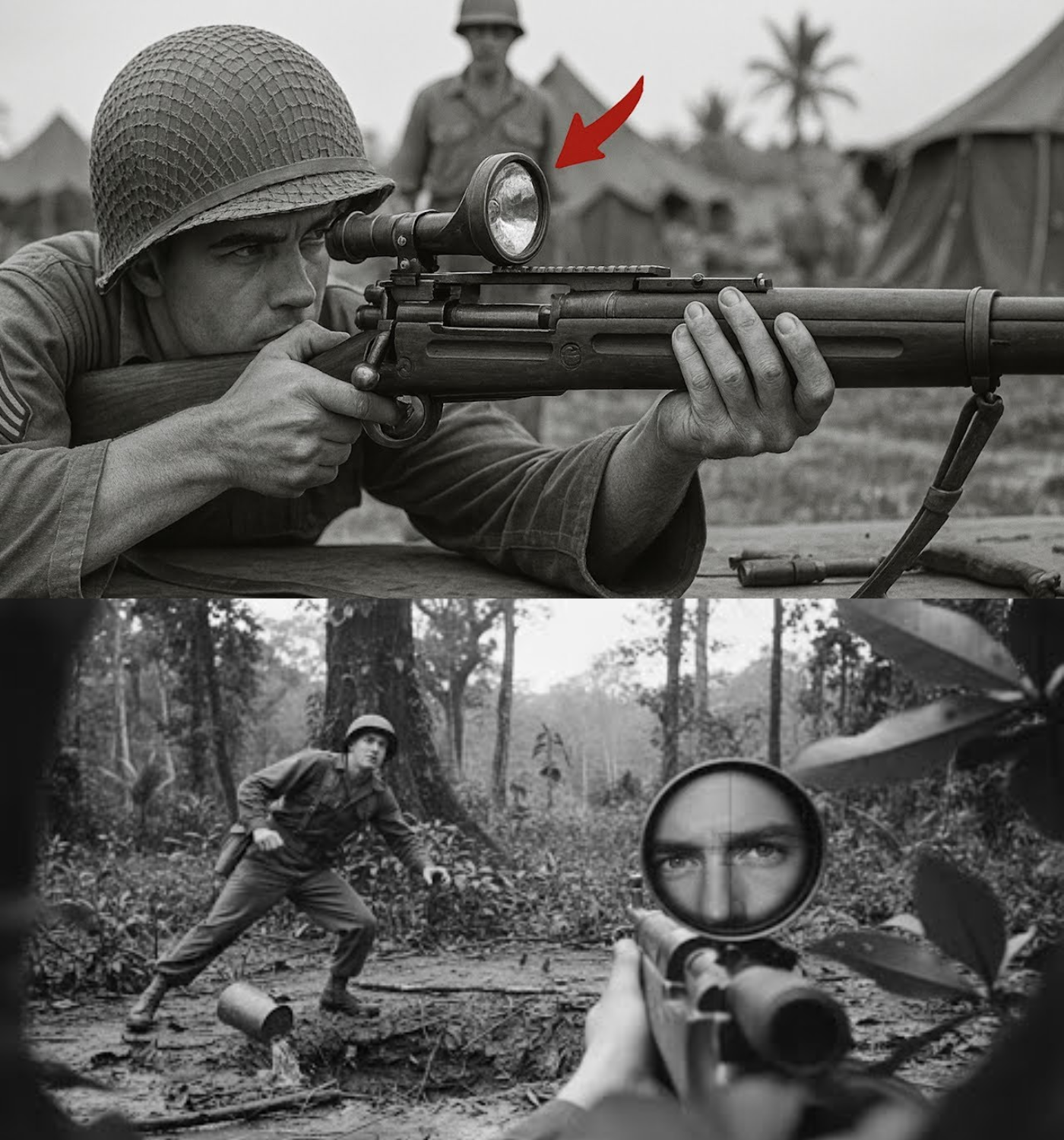

At 9:17 a.m. on January 22, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese bunker west of Point Cruz, his heart racing as he peered through the scope of his rifle. It was a Winchester Model 70, a weapon that had drawn laughter and scorn from his fellow officers for weeks. At 27 years old, John was determined to prove them wrong. He had no confirmed kills, but he had the skills of an Illinois state champion marksman, and he was ready to face the deadly snipers that had been terrorizing his battalion.

The Japanese had deployed eleven snipers in the Point Cruz Groves, and in just 72 hours, they had killed fourteen men from the 132nd Infantry Regiment. John’s commanding officer had dismissed his rifle as a “toy,” and his fellow platoon leaders had mocked him, calling it his “mail order sweetheart.” But John knew its worth. He had saved for two years to buy this rifle, and now it was time to see if it could make a difference in the fight against the enemy.

When John had unpacked the rifle at Camp Forest in Tennessee, the armorer had questioned whether it was meant for deer or Germans. John had insisted it was for the Japanese, but by the time the rifle arrived, he was already on his way to Guadal Canal. For weeks, he watched as others cleaned their Garands while his prized possession sat in a warehouse back home. Finally, it was delivered to him, and he was determined to use it.

The jungle around Point Cruz was a different battlefield than the one he had trained for. No bunkers or fixed positions—just Japanese soldiers hidden among the massive banyan trees, waiting to strike. The first few days had been brutal. John had watched as his comrades fell victim to the snipers, unable to pinpoint their locations. He had fired his rifle exactly zero times in combat, but that was about to change.

On the night of January 21, after yet another casualty report, John’s battalion commander summoned him. He needed someone who could shoot, someone who could stop the snipers before they claimed more lives. John explained his credentials: the Illinois State Championship at 1,000 yards in 1939, where he had set records with iron sights. The commander gave him until morning to prove his worth.

As dawn broke on January 22, John moved into position in the captured bunker, overlooking the coconut groves where the Japanese snipers were known to operate. He settled in, his heart pounding as he scanned the trees through his scope. The jungle was alive with sounds, but John had learned to filter out the noise and focus on movement. At 9:17, he saw it—a branch shifting slightly, no wind to account for it. He focused intently, and soon, he spotted the silhouette of a man, a Japanese sniper perched high in a banyan tree.

John adjusted his scope, controlling his breathing as he prepared to take the shot. With a gentle squeeze of the trigger, the rifle kicked against his shoulder, and the sound echoed through the jungle. The sniper jerked and fell, his body tumbling through the branches before hitting the ground with a thud. John worked the bolt with practiced ease, chambering another round and scanning for movement. He knew the sniper would have had a partner, and he had to be vigilant.

Minutes later, he spotted the second sniper moving down a different tree, retreating in the wake of the first shot. John aimed, fired, and once again, the sniper fell. Two shots, two kills. The adrenaline surged through him as he realized he could make a difference. Word spread through the battalion about the sniper who had mocked his rifle, and suddenly, men who had laughed at him wanted to watch him work. But John refused; he knew that spectators would draw attention and put him at risk.

As the morning wore on, John continued to eliminate threats, killing five Japanese snipers by noon. Each shot brought him closer to proving his worth, but as the day progressed, the Japanese adapted. They became cautious, ceasing their movements during daylight hours. John spent the afternoon scanning the trees, but the jungle fell silent.

The following day, January 23, began with heavy rain, obscuring visibility and making it difficult for John to spot any targets. However, as the rain let up, he resumed his watch and quickly found another sniper. He fired, and the Japanese mortars began to rain down around his position, having triangulated his location based on the gunfire. He narrowly escaped the destruction, relocating to a fallen tree where he continued to hunt.

On January 24, John faced his greatest challenge yet. He spotted a sniper in a palm tree, but something felt off. He realized it was a trap—a decoy. As he scanned the surrounding trees, he found the real threat hiding in a nearby banyan tree. He fired, killing the real sniper before he could react, but he had revealed his position to the remaining Japanese soldiers.

Suddenly, John found himself surrounded. As he fought to stay alive, he realized the odds were stacked against him. He had to break contact and move, using the jungle to his advantage. He sprinted through the undergrowth, dodging bullets as he made his escape. The sounds of chaos surrounded him, but he remained focused, knowing that survival was paramount.

Finally, he reached the American lines, reporting to Captain Morris about his successful engagement. In just four days, John had killed eleven Japanese snipers, a feat that would change the course of the battle. His actions had saved countless lives, proving that a man with a rifle and the right training could make a significant impact.

As the war continued, John George went on to train other soldiers, sharing his knowledge and experiences. His story became a testament to individual skill and determination in the face of overwhelming odds. The Winchester Model 70, the rifle that had once been the subject of ridicule, became a symbol of his legacy.

Years later, as John reflected on his experiences, he understood the evolution of warfare. The lessons he had learned on Guadal Canal and in Burma shaped his perspective on marksmanship and the importance of adapting to new challenges. He had witnessed the changing landscape of combat, but he never forgot the power of a single skilled marksman.

John George’s journey from a state champion to a decorated officer exemplified the spirit of resilience and courage. His story reminds us that in the chaos of war, it is often the individual actions of brave men that can change the tide of battle. His legacy lives on, not just in the history books, but in the hearts of those who continue to serve and protect.