This 17 Year Old Lied to Join the Navy — And Accidentally Cracked an Unbreakable Code

.

.

The Codebreaker: Andrew Gleason’s Unlikely Victory

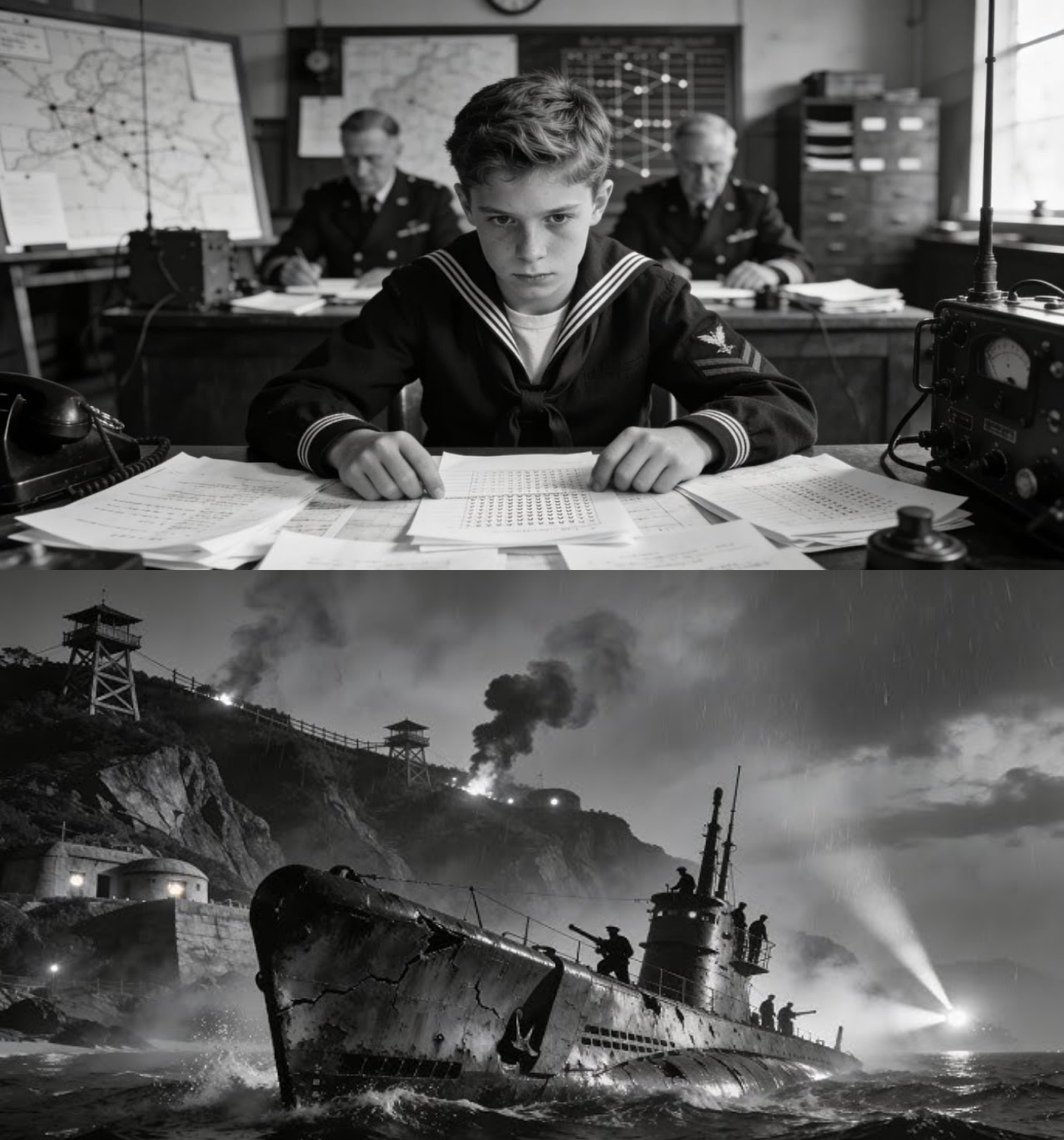

In the dimly lit basement of Building One at Pearl Harbor, the air was thick with the stench of sweat, cigarette smoke, and desperation. It was April 18, 1942, and Commander Joseph Rofort paced anxiously between rows of cramped desks, where weary Navy crypt analysts hunched over sheets filled with five-digit number groups. Each man in that room understood the grim reality—they were losing the war.

For 18 months, the Japanese naval code known as JN25 had eluded the brightest minds in the country. It was an impenetrable fortress, and every day that passed felt like a crushing defeat. The numbers taunted them, representing words, phrases, ship names, and locations, all hidden within a complex system designed to resist Western cryptanalysis. The Japanese had added layers of encryption, ensuring that even if the Americans intercepted a message, it would remain indecipherable.

The stakes were high. Since the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces had swept across the Pacific, capturing Wake Island and Guam, with the Philippines on the brink of collapse. American submarines roamed the ocean, blind and lost, while Japanese carriers struck with deadly precision. The kill ratio was staggering; for every Japanese ship sunk, America lost three. Admiral Nimitz needed to know where the enemy fleet would strike next, but all the intelligence officers could do was shrug at vast stretches of blue on the map.

What no one in that basement knew was that the breakthrough they desperately needed would come from the most unlikely source—a 17-year-old boy named Andrew Mate Gleason. He had lied his way into the Navy with a forged birth certificate, claiming to be 19, and his voice still cracked at the most inopportune moments. Andrew was not a trained cryptanalyst; he was just a kid who had stumbled into a world of codes and secrets.

Andrew was born on November 4, 1921, in Fresno, California, to a botanist father and a Swiss-American mother. While his peers were preparing for college, he felt a sense of urgency after witnessing the devastation at Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, he stood before a Navy recruiter, eager to enlist. The recruiter eyed him skeptically, noting his slight frame. “You sure you want this?” he asked. Andrew nodded, driven not just by patriotism but by a restless boredom that had consumed him.

Assigned to OP20G, the Navy’s cryptanalysis division, Andrew spent his days sorting through intercepted messages, an unremarkable task for a boy who longed to solve puzzles. He wasn’t allowed to work on actual cryptanalysis, but he couldn’t help but notice patterns in the chaos around him. As he sorted through thousands of messages, he became increasingly aware of inconsistencies that others overlooked.

By April 1942, Andrew had been sorting messages for ten weeks when he made a discovery that would change the course of the war. It was 2:00 a.m., and instead of sleeping, he was in the cryptanalysis room, spreading out 60 intercepted messages from the same Japanese transmission station. He noticed that the metadata at the beginning of the transmissions only used the first 13 letters of the alphabet for messages sent from Tokyo to Berlin, while the reverse was true for messages sent from Berlin to Tokyo.

What if, Andrew wondered, the unencrypted indicators followed the same pattern? If he could assume that the plain text structure of the indicators mirrored this split, he might be able to recover part of the additive table used in the encryption. His heart raced as he worked through the math, realizing he could recover indicator additives with 73% accuracy.

But who would listen to a kid with no formal training? When he approached Lieutenant Commander Howard Angstrom to share his findings, he was met with skepticism. “Not now, Gleason. We’re busy,” Angstrom dismissed him. Despite his frustration, Andrew continued to refine his discovery in silence, improving his accuracy to 81% over the next three weeks.

Then, on May 11, 1942, everything changed. Admiral Nimitz arrived at Building One for an emergency briefing. Japanese radio traffic had surged, and the cryptanalysis team was struggling to pinpoint the location of an impending major offensive. The pressure was palpable as Rofort presented their findings, revealing that they could only read about 5% of the current JN25 traffic.

In that tense moment, Andrew’s body moved before his mind could catch up. He stood up, breaking all protocol. “Sir, I think I know how to break the additives,” he blurted out. The room erupted in chaos, officers shouting over one another, incredulous that a seaman apprentice would dare to speak up. Rofort looked at him, weary and incredulous, but Admiral Nimitz raised a hand for silence.

“Let him speak,” Nimitz commanded.

With his heart pounding, Andrew explained his hypothesis about the indicator headers and the split alphabets. As he spoke, he could feel the weight of the room’s skepticism, but he pressed on, showing his calculations. To his surprise, Lieutenant Commander Dyer leaned in, intrigued by the math. The atmosphere shifted as officers began to see the potential in Andrew’s method.

Commander Rofort, recognizing the gravity of the situation, turned to Andrew. “How old are you?” he asked, his voice steady.

“19, sir,” Andrew replied, knowing his lie was hanging in the air.

“Uh-huh. And I’m the Queen of England,” Rofort replied skeptically.

But Admiral Nimitz, recognizing the urgency, made a decision. “Test it. You have 72 hours. If it works, I want every available cryptanalyst implementing Gleason’s method immediately.”

The next 72 hours were a whirlwind. Andrew Gleason, who had been sorting messages just weeks before, found himself working alongside the top cryptanalysts in the Navy. They divided into teams, some continuing traditional attacks on JN25 while others tested Andrew’s method. As they worked through intercept after intercept, Andrew’s technique proved faster and more effective than anything they had tried before.

Within 16 hours, they began recovering enough additives to strip encryption from current traffic. By hour 36, they were reading fragments of operational orders. And by hour 60, they confirmed Rofort’s suspicion: the location designated as AF was Midway Island. The Japanese were planning a massive carrier strike.

On June 4, 1942, the battle began. American dive bombers caught three Japanese carriers with their decks full of armed aircraft, resulting in a devastating blow to the enemy fleet. The Battle of Midway became a turning point in the Pacific War, largely thanks to Andrew’s breakthrough.

In the aftermath, Andrew’s method evolved into a comprehensive system for attacking additive tables. By the end of 1942, OP20G was reading 75% of JN25 traffic, saving countless American lives. Andrew Gleason had transformed from a mere message sorter into a pivotal figure in the war effort, proving that sometimes, fresh eyes on a problem could lead to extraordinary solutions.

As the war continued, Andrew’s contributions remained classified. He eventually returned to college, fulfilling Admiral Nimitz’s promise that he would teach cryptanalysis to the next generation. Though he achieved great success in mathematics and academia, he never spoke much about his time in the Navy.

Andrew Gleason passed away on October 17, 2008, at the age of 86. His legacy, however, lived on, not just in the annals of military history but in the hearts of those who understood the value of perseverance, innovation, and the courage to speak up—even when the odds were stacked against you. His story is a testament to the power of fresh perspectives and the impact that one determined individual can have on the world.