“Bigfoot Saved My Partner” — A Veteran’s Unforgettable Sasquatch Encounter Story of Survival and Unexpected Heroism

I Never Believed in Bigfoot Until One Saved My Best Friend’s Life in Montana

This happened three years after we both returned from deployment. And I know how it sounds. I know exactly how crazy the story is. But I carry what happened with me for the rest of my life.

My buddy and I served together overseas, in the same unit, two full tours— the kind of friendship you only get when you’ve been through absolute hell with someone. During those long nights in the desert when we couldn’t sleep and the heat was unbearable, we’d talk about what we’d do when we got home.

.

.

.

One promise we made to each other was that we’d do a proper hiking trip once we were back in the States. No gear, no mission, no one shooting at us. Just two friends in the mountains. It took us almost three years to make it happen. Life got complicated after we came home. We both had families to reconnect with, jobs to figure out—the whole process of readjusting to civilian life that nobody really prepares you for.

There were times when it felt like the trip was never going to happen. We’d make plans, then something would come up. Work schedules wouldn’t line up. Kids got sick. Life just kept getting in the way. But that September, everything finally aligned.

Three days in the Montana backcountry. We picked a remote section of the Bitterroot Range—the kind of place where you can hike for days without seeing another soul. The wilderness we’d been dreaming about. We weren’t going in unprepared. We’d done our homework, spent weeks studying maps, checking weather forecasts, planning our route. We packed the right gear, brought plenty of supplies, made sure someone knew where we were going and when we’d be back.

Both of us had wilderness training from the military. Plus, we’d grown up hunting and camping in similar terrain. We knew what we were doing. We respected the mountains, and we weren’t taking any chances.

The weather was perfect when we started out—early September, that sweet spot before the real cold sets in. But after the summer crowds had cleared out, the trailhead parking lot was empty except for our truck when we arrived just after dawn. We shouldered our packs, checked our gear one more time, and headed into the trees. The air was crisp and clean, smelling of pine and earth.

The first day went exactly as we’d hoped. We covered good ground—maybe 12 miles through some beautiful country: rolling hills covered in pine and fir, occasional meadows full of wildflowers even this late in the season, streams running clear and cold. We stopped for lunch by a waterfall, watched the water cascade over moss-covered rocks, and set up camp that first night by a creek—the sound of flowing water lullabying us to sleep.

We sat around the fire for hours, talking about everything since we’d gotten back—jobs, families, friends we’d lost touch with, the ones we’d kept. It felt good to be out there with him again, back in that easy rhythm we’d had overseas, but without the weight of everything else pressing down on us.

The second day started just as well. We broke camp early, maybe 6 a.m., and hiked through some of the most beautiful country I’d ever seen. Pine forests stretching as far as the eye could see, granite peaks catching the morning light and turning pink and gold. Meadows full of wildflowers still blooming, even this late in the season. We saw a herd of elk—about 20—grazing in a clearing, watched them for a while through binoculars, then moved on.

We stopped for lunch by another creek, ate our trail food, joked around like we used to, talked about doing this again next year—maybe bringing our kids if they were old enough, making it a tradition. The afternoon was warm but not hot—perfect hiking weather. We followed a trail that ran parallel to a creek bed, planning to find a good spot to camp in another hour or two. The trail was rocky, the kind where you had to watch your footing, but we were experienced enough that it wasn’t a problem.

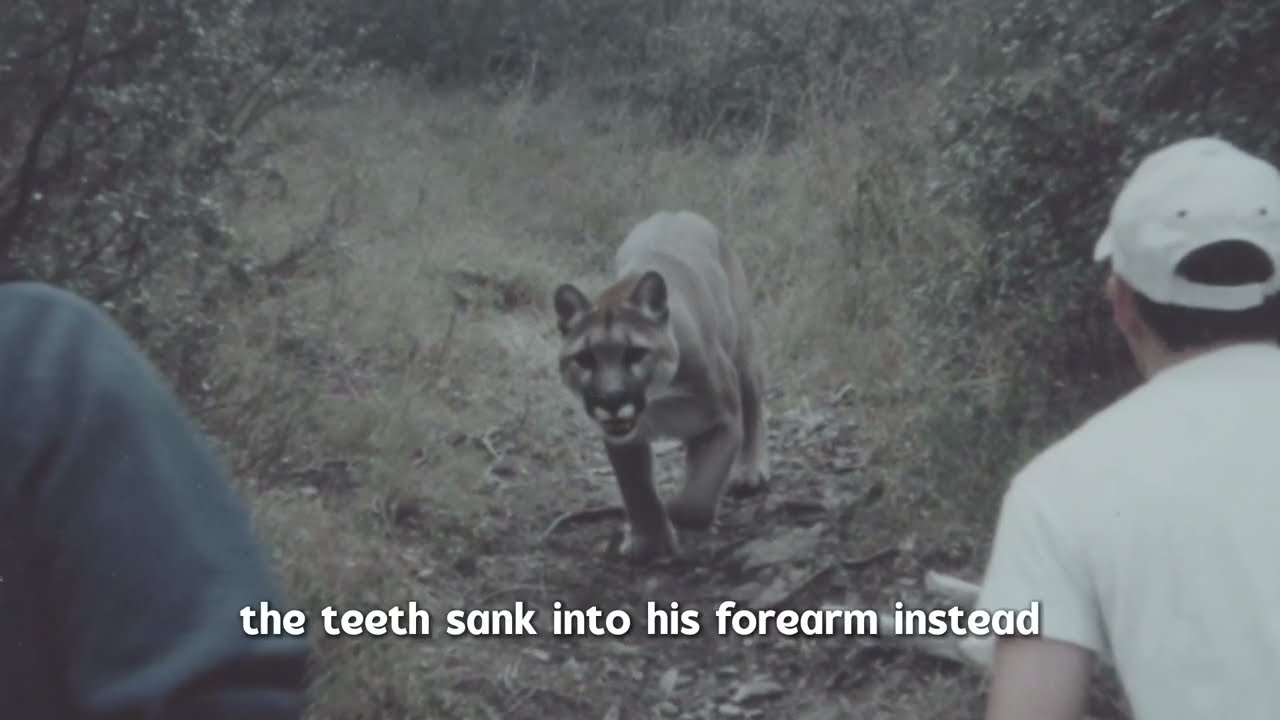

We’d been moving for about six hours, covering good distance, when everything changed. Around 4 p.m., we rounded a bend in the trail. Maybe 40 yards ahead of us, right in the middle of the path, was a mountain lion. Big one, too—probably 150 pounds, tawny coat rippling over heavy muscles, tail twitching slowly like a predator watching a prey.

It had already spotted us. Those yellow eyes were locked on us, ears forward, completely focused. There was no surprise in its posture. It had known we were coming and had chosen to wait for us.

We both froze instantly. Training kicked in without us even thinking about it. Make yourself big. Don’t run. Whatever you do, don’t run. Running triggers the chase instinct, and you’ll never outrun a mountain lion anyway.

We raised our arms above our heads, spreading our jackets to look as large as possible. Started backing away slowly, maintaining eye contact. My buddy had his trekking poles up, trying to look even bigger and more threatening. I kept my arms wide, holding my jacket out like wings, moving backward one careful step at a time.

But this cat wasn’t backing down. It just stood there, watching us with those predator eyes. When we took a step back, it took a step forward, matching us move for move, keeping that same distance. The standoff stretched on—five minutes, then ten. My arms were aching, shoulders burning. Sweat was pouring down my back despite the cool mountain air.

Fifteen minutes. We kept retreating, step by step. The cat kept following—never rushing, never retreating—just watching, waiting, like it had all the time in the world and knew we didn’t.

I could hear my buddy’s breathing getting harder beside me. I saw the sweat soaking through his shirt despite the cool air. The stress was getting to him. His face had gone pale. His arms shook from holding them up so long. I wanted to tell him to hang in there, to keep it together, but I didn’t dare break the silence. Didn’t dare do anything that might trigger the cat.

Twenty-five minutes into this standoff, disaster struck. My buddy’s boot caught on something behind him—I didn’t see what, an exposed root, a hole in the trail, I don’t know. But one second, he was backing up steadily, and the next, his foot hooked on something, and he stumbled backward. His arms flailed trying to catch his balance. That split second of eye contact with the cat was all it took.

The mountain lion charged. I’ve never seen anything move that fast in my life. One second, it was 40 yards away. The next, it was airborne, covering the distance like it had been shot from a cannon. Its muscles bunched and released, launching it forward in huge bounds that ate up the ground between us.

My buddy was still trying to regain his footing, still off balance and vulnerable when that cat launched itself through the air, directly at him. I didn’t think—just reacted. I threw myself forward, swinging my pack at the blur of tawny fur and muscle. I hit it mid-leap, managing to knock it slightly off course— but not enough. Not nearly enough.

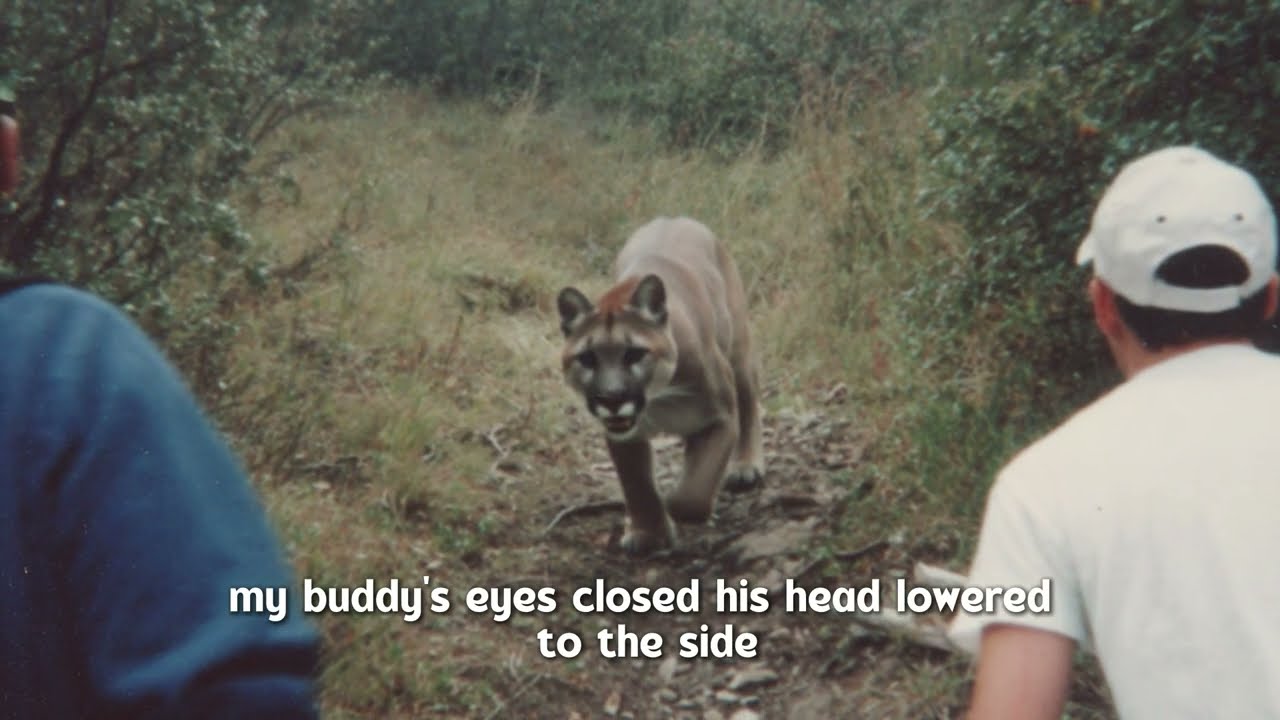

The cat landed on my buddy’s chest, claws out, and I heard the fabric of his jacket tear. I heard him scream—a raw, pure terror and pain. The claws raked across his shoulder and chest, opening long gashes through his jacket and shirt. The cat’s jaws snapped toward his throat—going for the kill—and my buddy threw his arm up instinctively to protect himself. The teeth sank into his forearm instead—puncturing skin and muscle. I heard him scream again.

I was screaming, too. I couldn’t even tell you what I was saying—just noise, rage, terror. I kicked at the cat with my hiking boot—connected with its ribs. I grabbed a thick branch from the ground—deadwood, heavy—and started swinging it like a baseball bat. Hit the cat once across its back, then twice across its shoulders. It finally let go of my buddy’s arm, backed off a few feet, hissing like a nightmare creature.

Its lips pulled back, teeth stained with my buddy’s blood. I grabbed my buddy’s good arm and dragged him backward, putting myself between him and the cat.

I got a good look at the damage for the first time, and my stomach dropped. Deep claw marks across his chest and shoulder—four parallel gashes already soaked in his blood. The fabric torn open, revealing deep, angry wounds. Puncture marks on his forearm, bleeding heavily. But the worst was his neck—one of those claws had caught him just below his jaw on the right side. Not directly on the main vein, thank God, but close enough I could see it pulsing under the torn skin. Close enough that if it had been an inch to the left, he’d already be dead.

He was conscious, but going into shock—eyes wide, pupils dilated, skin pallid, breathing rapid and shallow. His good hand was clutching his chest, trying to stop the bleeding, but there were too many wounds. The cat was circling us now—maybe 20 feet away, tail twitching. It wasn’t leaving. It had tasted blood, and it knew one of us was hurt—vulnerable, easy prey.

I tore open our first aid kit with trembling hands, trying to keep an eye on the cat. My hands wouldn’t stop shaking. Adrenaline made everything feel surreal—as if I was watching this happen to someone else. I tried to pack the neck wound first—most dangerous. But the blood was coming too fast. Bandages soaked through as quickly as I could apply them. Blood ran down into his collar. His lips were losing color—pink, pale, almost white. He was mumbling—maybe my name, maybe his wife’s—I couldn’t tell.

The cat moved closer—about 15 feet now—doing a mock charge. Darting forward a few steps, then backing off, testing us. I yelled at it, waved the branch, tried to look big and threatening again. It didn’t care anymore. It had seen weakness, and it wasn’t leaving. It knew it just had to wait.

The sun was sinking fast. Maybe an hour of daylight left. Shadows stretched between the trees. The temperature was dropping. I knew we couldn’t move him. He’d lost too much blood. Moving him now would probably kill him—open the wounds again, make him bleed out faster. We were stuck here for the night, whether we liked it or not.

The creature was still standing there—about ten feet away now, watching us. I didn’t know what else to do. Didn’t know if it could understand me. But I tried talking anyway. My voice was rough, trembling.

“Thank you. He’s hurt bad. I don’t know what to do.”

It looked at me for a long moment—those dark eyes studying my face like it was trying to read my expression. Then it grunted once—a short, low sound that might have been acknowledgment. Turned and walked back into the forest, moving with surprising grace for something so large. Just like that, it was gone—disappeared into the shadows between the trees.

I thought that was it. That we were alone again. Part of me wondered if I’d hallucinated the whole thing—that the stress and adrenaline had made me see something that wasn’t there. But I could still hear it moving through the forest—branches snapping in the distance. It was real. It had been there. I tried to keep my buddy warm, wrapping him in my jacket and the emergency blanket from the first aid kit. I checked his pulse every few minutes—weak, irregular, but still there.

Ten minutes later, the creature returned—moving quickly, carrying different plants: some kind of bark, broad green leaves, dark berries. It sat beside us and did something that made my stomach turn a little. It put the bark in its mouth, chewed it, then spat the paste into its palm—reddish, fibrous, wet. Carefully, it packed that pulp into the worst wounds—deep claw marks on his chest. My buddy screamed—raw, agonized—echoing through the woods. His whole body tensed, arching, clawing at the ground.

The creature flinched—like it had hurt him on purpose. I saw conflict in its eyes. It knew this was painful, but also knew it might help. It knew it was necessary.

“Keep going, please. He needs it,” I begged.

It nodded and finished packing the wound. Then it laid the broad leaves over the pulp, creating a sort of poultice. It tied the leaves in place with strips of bark, working with shocking precision and delicacy. The berries it crushed in its hands, smeared the juice around the wounds—something I had no idea what it was, but clearly knew what it was doing.

When it was done, my buddy settled. The screaming stopped. His breathing evened out—weak but steady. The creature lifted him carefully, supporting him as it moved. We moved faster now—almost running. Its long legs ate up the ground at a pace I could barely keep up with. My legs burned, lungs aching, sweat pouring down despite the cool air.

Every time I fell behind, it slowed, waited, then resumed. Never left me. Never left him.

Around mid-morning, about three hours from the trailhead, we stopped at a stream. Crystal clear water flowing over smooth stones, worn down by centuries. The creature gently set my buddy down at the water’s edge. It splashed cold water on his face, poured it over his forehead, trying to bring down the fever.

My buddy’s eyes fluttered open briefly. He looked at the creature—no fear, just confusion, like he was seeing a dream he couldn’t wake from.

The creature made a soft sound—almost like a chuckle. Breaths through its nose, shoulders shaking slightly, as if amused. It helped me give him small sips of water, supporting his head with one massive hand while I held the bottle. He drank a little, coughed, then closed his eyes again, slipping back into unconsciousness.

I took that moment to ask something that had been nagging at me: “Do you have a name?”

The creature looked at me for a long moment—those dark eyes studying my face, like it was deciding how much to reveal. Then it tapped its chest, slowly, deliberately. The words came slowly, like they were difficult to form:

“Old. Very old.”

The weight of that word settled over me like a heavy blanket. The loneliness, the sadness, the finality. “You’re alone. The last one.” It nodded slowly.

Its eyes never left mine. Alone. How long?

It seemed to struggle with the concept of time. It pointed at the sky, made a circular motion with its finger like the sun going around, then held up both hands, flicking all its fingers multiple times. I got the impression it was trying to communicate years, decades—maybe longer. Maybe it had been alone so long it had lost track.

“I’m sorry,” I said softly. That must be hard.

It made a quiet sound—like a sigh or a grunt. Then it shrugged—a very human gesture, like it had made peace with it long ago. Like loneliness was just part of its existence.

Now is away. Those two words carried so much weight—acceptance, resignation, the understanding that some things just can’t change—they only have to be endured.

We rested for a few more minutes. I shared some of our food—jerky, trail mix, energy bars. The creature examined the jerky, turned it over, sniffed it, then ate it with a pleased grunt. It studied the trail mix—so many different things mixed together—and surprised me by eating the M&Ms first, savoring each one. Then it ate the nuts and dried fruit.

A simple moment of connection—two beings sharing a meal. Building trust, maybe understanding, a bridge between worlds that had been separate for so long they’d almost forgotten each other.

When we were ready to move, the creature did something unexpected. It took one of my water bottles, filled it carefully from the stream, then tucked it into the layers of bark and leaves wrapped around my buddy. It created a makeshift pocket to carry water later, planning ahead.

We moved on. The creature cradled my buddy again, supporting him as we followed paths only it could see—deeper into the forest, toward help I hoped was still nearby.

By early afternoon, my buddy was worsening again. His skin had turned gray—unhealthy, frightening. His breathing was shallow, each breath labored. The infection was spreading. We were maybe three hours from the trailhead, but I wondered if we could make it.

The creature moved faster—almost running now, its long legs eating up the ground. Sweat poured down my face, lungs burning. Every step I took, I fell farther behind. It kept waiting, slowing just enough for me to catch up, then resuming its pace. Never leaving me behind.

Around mid-morning, we stopped at a stream. Crystal clear water flowing over smooth stones. It gently set my buddy down, splashed cold water on his face, poured water over his forehead, trying to lower his fever. His eyes fluttered open briefly. He looked at the creature—no fear, just confusion—like he was seeing something from a dream.

The creature made a soft chuckle-like sound. It supported him carefully, then looked at me with those dark, intelligent eyes, as if it understood everything.

“Thank you,” I whispered. “He’s hurt bad. I don’t know what to do.”

It looked at me for a long moment—those eyes studying my face—then nodded. It was like it was saying, “We’re okay. For now.” Then, it lifted him again, cradling him with gentle strength, and we headed deeper into the woods, following paths only it could see, toward help I hoped was close enough.

And then, everything changed.

Around two in the afternoon, about two and a half hours from the trailhead, my buddy stopped breathing. One second, he was gasping, and the next, he was gone. Silence. The creature paused immediately, laid him down gently, and looked at me with wide, worried eyes.

I dropped to my knees beside him, checked for a pulse—weak, faint, but there. His lips were blue, his skin cold. No. No, no, no. I started chest compressions, counting in my head—30 compressions, two breaths. The creature watched silently, still and patient.

I did another round. Still no response. His chest moved with the compressions, but he wasn’t breathing on his own. I begged silently—“Come on. Come on. Don’t do this now. Not when we’re so close.”

The creature made a low, urgent sound. Then it gently pushed me aside, placed one massive hand over my buddy’s chest, and pressed down—surprisingly gentle but firm. Once, twice, three times. Then it leaned down, breathed into his mouth, covering his nose and mouth with its own. One breath. Two.

My buddy’s chest rose. fell. Rose again. And he gasped—a huge, shuddering breath—and started breathing on his own, shallow and weak but breathing.

The creature sat back, relief clear on its face. It looked at me and nodded. “We’re okay. He’s okay—for now.” But we both knew we were out of time.

The creature lifted him even more carefully than before, holding him like he was made of glass. Then it started running—faster than I thought possible, covering ground at a pace I could barely keep up with.

I ran after it, ignoring the pain in my knee, ignoring my burning lungs, ignoring everything except that massive shape ahead. About forty-five minutes later, I started to hear something—voices. Human voices, distant but growing closer. People on the trail.

The creature heard them too. It stopped, set my buddy down behind a fallen log, and pushed me down beside him. Put one massive finger to its lips—the same gesture humans use. Silence. Be quiet. I understood. It couldn’t be seen. It couldn’t risk anyone knowing it existed.

But we were close to help now. Close enough to be rescued. The creature seemed torn—like it was deciding whether to stay hidden or make sure we got out.

I made the decision for both of us. “Go,” I whispered. “We’ll be okay now. Those people will help us. You’ve done enough. More than enough.”

It looked at my buddy, then back at me. The hesitation was clear. It didn’t want to leave before seeing us to safety. Didn’t want to trust that we’d be okay. “Please,” I begged. “You can’t be seen. But we’ll make it from here. I promise.”

The creature hesitated, then reached out and touched my buddy’s forehead one last time, holding its hand there for several seconds—like it was saying goodbye, checking once more that he was still breathing.

Then it looked at me and spoke more words than I’d ever heard it say at once. “He fight. You fight strong. Both strong.”

Then it reached out and gently patted my shoulder—the same gesture as before. “Man help man is way. You remember?” I would. I never would forget. I promised.

It nodded, seemingly satisfied. Then it looked around one last time, listening to the approaching voices. They were close now—about three minutes away.

The creature turned and moved toward the shadows of the trees. But before disappearing entirely, it stopped, looked back at us one last time, raised one hand—more like a farewell, a blessing—and then melted into the forest like smoke, as if it had never been there at all.

I waited maybe thirty seconds, making sure it had time to get clear, then started yelling for help as loud as I could.

The hikers found us within minutes—a couple in their 50s, experienced outdoorsmen. They took one look at my buddy and immediately pulled out a satellite phone, called emergency services, and started treating him with their first aid kit. They kept asking what had happened, how we survived, how I managed to treat him so well. I told them a story I didn’t think about too much—mountain lion attack. I’d fought it off with a stick. We’d spent the night here. I’d used wilderness medicine to treat him. He was in bad shape, but hanging on.

They didn’t question it. Why would they? The evidence was all there—wounds, blood, exhaustion. They had no reason to doubt me. No reason to think anything strange had happened.

The helicopter arrived thirty minutes later. They stabilized my buddy enough for transport and flew him out. The hikers helped me make it to the trailhead, let me lean on them when my legs finally gave out, and got me to my truck.

I sat in the driver’s seat for several minutes before starting the engine. Just sat there, looking at the forest, hoping to see that massive shape one more time—hoping for one more chance to say thank you, to tell it I understood what it had done, what it had sacrificed, the loneliness it endured, the risks it took.

But the forest was silent—quiet, like it always appears to most people. Like nothing unusual lived there at all.

I started the truck and drove to the hospital—most of it a blur. I just gripped the wheel and drove, trying not to think about what I’d seen, what I’d experienced, what I knew to be true but could never prove.

My buddy survived three surgeries and five days in intensive care. The doctors were amazed. Said someone must have known advanced wilderness medicine. The plant-based remedies had probably saved his life. They said it kept the infection from spreading as fast as it should have, kept him alive long enough to get help.

They called me a hero. Said my buddy was lucky to have me there. But I knew the truth. I wasn’t the hero. Something else had saved him—something that shouldn’t exist, something that showed more compassion, skill, and dedication than most humans ever would.

When my buddy finally woke up after the surgeries, antibiotics, and transfusions, he had fragmented memories. Something big and dark watching over him. Feeling safe despite everything. A sense that someone was taking care of him.

He couldn’t piece it all together. I didn’t push it. I just told him he’d been delirious with fever, that he’d been dreaming. We agreed—without really discussing it—not to tell anyone the real story. Who would believe us anyway? A guy in a costume—that’s what we’d say if anyone pressed. Some eccentric wilderness hermit who’d helped us out. Strange, but harmless. Better than the truth, which would make us sound crazy.

A month later, I went back to that spot alone. Hiked the same trail. Found the place where the mountain lion had attacked us, where the creature had first appeared. I left supplies at the edge of the forest where it had stopped that last time—beef jerky, nuts, dried fruit, energy bars, a good camping knife, a warm blanket—things it might need, things I wanted it to have.

The next day, they were gone—no sign of animals, no scattered supplies. Just gone. Taken. The blanket, the knife, the food—all of it. I like to think it knew who left them, understood what they meant.

Thank you. I remember. I’m grateful.

I never saw it again. Never found any other trace of it. But sometimes, hiking in those mountains, I swear I hear that distant call— that scream that doesn’t sound like any animal I’ve ever known. That impossible sound that belongs to something that shouldn’t exist.

And I know—we’re not alone out there. I know there’s something in those mountains watching over the wilderness. Something old, solitary, and kind.

My buddy and I are different now. We don’t talk about it much, but it’s there between us—the knowledge that something impossible happened, that something that shouldn’t exist saved his life, changed both our lives. We see the wilderness differently now. Look at the forests with more respect, more wonder, more understanding that we’re not the only ones out there—that we never were.

And on quiet nights, when I’m home with my family and the world feels small and ordinary and known, I remember those dark eyes looking at me across a fire. That rough voice saying, “Man, help man.” That gentle touch on my shoulder. And I know that the world is bigger and stranger and more wonderful than we allow ourselves to believe.

That’s my story. Take it or leave it.

Believe it or not, I know what happened. I know what I saw. And I know that somewhere in the Montana wilderness, something walks that defies everything we think we know about the world. Something that chose compassion over safety, connection over solitude, help over hiding. And I’ll spend the rest of my life grateful for that choice.