Camera Captures Bigfoot’s Face Near the Woods—But What Happened Next Was Truly Shocking: Real Sasquatch Encounter Story

The Reflection: What My Camera Saw—and What Saw Me

Chapter 1: The Impossible Photograph

Listen, what I’m about to tell you sounds absolutely insane. And honestly, if someone told me this story a year ago, I would have laughed in their face. But I’ve got proof. Actual photographic evidence. And after what happened to me in those woods, I’ll never look at a trail camera the same way again.

This is the story of how I captured a Bigfoot’s face on camera. And how that single photograph changed everything I thought I knew about the wilderness.

.

.

.

Chapter 2: The Wildlife Photographer

I’m a wildlife photographer by trade and I spend about half the year documenting animals in their natural habitats across the Pacific Northwest. My specialty is elusive creatures: lynx, wolverines, mountain lions—the kind of animals most people never see in person. I use trail cameras extensively, sometimes setting up 20 or 30 across a single mountain range to capture footage of these rare species. The cameras are motion activated, weatherproof, and can record for months without needing attention.

Last October, I was hired by a conservation group to document wildlife activity in a remote section of the Cascade Mountains. The area was pristine: old growth forest, minimal human traffic, and reports of healthy populations of elk, black bears, and even the occasional gray wolf.

I spent three days hiking into the back country, placing cameras along game trails, near water sources, and in areas where I’d spotted scat or tracks. By the time I finished, I had 24 cameras positioned across roughly 40 square miles of wilderness.

The plan was simple. Leave the cameras for six weeks, return to collect the memory cards, and compile the footage into a comprehensive wildlife survey. I’d done this dozens of times before without incident. The cameras would capture thousands of images, mostly deer, squirrels, and birds. But occasionally, you’d get something special: a bear fishing in a stream, a mountain lion stalking prey. Those were the moments that made the long hikes and cold nights worthwhile.

Chapter 3: The Ravine and the Omen

Each camera location required careful consideration. I looked for natural funnels where animals would be forced to pass: narrow sections of trail, creek crossings, areas between fallen logs. I noted wind direction, ensuring my scent wouldn’t carry to the trail during installation. I checked for clear lines of sight, making sure branches wouldn’t trigger false alerts. Every detail mattered.

The first 16 camera locations went smoothly. Good trees, solid mounting points, clear views. By the third day, I’d fallen into a comfortable rhythm. Hike, scout, position, test, move on. The mountains were beautiful in that late October light, golden larches among the evergreens, morning frost sparkling on the undergrowth.

Camera number 17 was different from the start. I positioned it deep in a ravine near a creek that cut through a particularly dense section of forest. The trees were massive Douglas firs and western red cedars that had been growing for centuries. The canopy was so thick that even at midday, the forest floor remained in twilight.

Something about the place felt heavy, oppressive. I remember hesitating before mounting the camera, getting this weird feeling in my gut that I should just skip this location and move on. But I’d hiked four miles to get there, and the game trail showed clear signs of regular use. The signs were unmistakable: deep tracks in the soft earth near the creek, larger than any elk or deer would make; scratch marks on trees at unusual heights, too high for a bear to reach comfortably; broken branches snapped at angles that suggested something pushing through rather than climbing over.

I told myself these were just normal forest conditions, but part of me knew I was lying. These weren’t normal. These were the marks of something big moving through the forest with purpose and power.

I strapped the camera to a tree trunk about six feet off the ground, angled it toward the trail, and tested the motion sensor. Everything worked perfectly. As I turned to leave, I heard something in the distance—a low, guttural sound that didn’t match any animal I knew. It wasn’t a bear grunt or an elk bugle. It was deeper, more resonant, and it seemed to echo through the ravine in a way that made my skin crawl.

I stood there for a full minute listening, but the sound didn’t repeat. I convinced myself it was just the wind moving through the trees, or maybe a distant rock slide.

Chapter 4: The Wait

The next six weeks passed normally. I worked on other projects, processed footage from previous assignments, and tried not to think too much about the cameras waiting in the mountains. Trail camera work requires patience. You never know what you’re going to get until you retrieve the memory cards. Sometimes you come back to thousands of useless images. Other times you strike gold.

During those weeks, I completed two other assignments. One involved documenting urban coyotes adapting to city life in Seattle. The other tracked mountain goat populations in the North Cascades. Both projects went smoothly, yielding predictable results. The coyotes raided garbage cans and hunted rats. The mountain goats grazed on alpine meadows and navigated impossible cliff faces. Normal wildlife behaving normally.

Nothing prepared me for what was waiting on those memory cards in the mountains.

I kept having dreams about camera 17. Nothing dramatic or nightmare-inducing, just recurring images of that ravine, those massive trees, that oppressive darkness. In the dreams, I’d be standing at the camera location, looking into the forest, and I’d have the distinct impression that something was looking back—not threatening, not aggressive, just watching, waiting.

Chapter 5: The Return

In late November, I made the trek back into the Cascades to collect my cameras. The weather had turned cold, with snow dusting the higher elevations. I started with the cameras closest to the trailhead and worked my way deeper into the back country. Most of the footage was exactly what I expected: deer browsing, raccoons investigating the cameras, the occasional coyote passing through. Nothing unusual, nothing concerning.

Camera 17 was the last one on my route, and reaching it required the same four-mile hike through increasingly rugged terrain. As I descended into the ravine where I placed it, that same heavy feeling returned. The forest seemed quieter than it should be. No birds calling, no squirrels chattering, just the sound of my boots crunching through frost-covered leaves and the distant gurgle of the creek.

When I reached the tree where I had mounted the camera, I immediately noticed something was wrong. The camera was still there, still strapped securely to the trunk, but the tree itself showed damage—deep gouges in the bark starting about three feet off the ground and extending up past where the camera was positioned. The marks were fresh, recent enough that sap still oozed from the wounds. They looked like claw marks, but they were too large to be from a bear, and the pattern was wrong. Bears leave parallel scratches. These marks were more erratic, almost deliberate.

I unstrapped the camera with shaking hands, half expecting it to be destroyed, but the housing was intact, the lens unscratched. Whatever had clawed the tree had deliberately avoided damaging the camera. I powered it on to check the battery—still at 60%. The memory card was full, completely full. That was unusual. Six weeks of recording should fill maybe half the card, unless the camera had been triggered constantly.

Chapter 6: The Footage

I didn’t wait to get home to start reviewing the footage. As soon as I was back at my truck, I pulled out my laptop and inserted the memory card from camera 17. The file directory showed 8,647 images and 312 video clips. My heart rate picked up. That was an extraordinary amount of activity for a single camera location.

The first few hundred images were normal. Deer passing through at dawn and dusk. A black bear investigating the area in early October. Smaller creatures—martens, weasels, pine squirrels—darting across the frame.

Then on day 12, the footage changed. The timestamp showed 11:47 p.m. when the first unusual image appeared. The photo was dark, illuminated only by the camera’s infrared flash. In the center of the frame stood a figure. It was massive, at least seven or eight feet tall, with broad shoulders and long arms that hung past its knees. The body was covered in dark hair or fur, and the proportions were wrong for a human. The legs were too thick, the torso too barrel-shaped.

But what stopped me cold was the way the Bigfoot was positioned. The creature wasn’t just passing through the frame. It was standing directly in front of the camera, perfectly centered, as if it knew exactly where the lens was.

Chapter 7: The Face

I clicked to the next image. Same position. The Bigfoot hadn’t moved. The timestamp showed only two seconds had passed. Another click—still there. The Bigfoot remained motionless, just standing and staring at the camera. I scrolled through 20 consecutive images, all showing the same scene: the Bigfoot standing, watching, waiting.

Then the footage jumped forward three hours. The next triggered image showed the trail empty again. Whatever had been there was gone.

My hands were trembling as I continued through the files. For the next week, the camera captured only normal wildlife activity. Then on day 19, the Bigfoot returned. This time, the encounter lasted longer. The image sequence began at 2:14 a.m. The Bigfoot entered the frame from the left, moving with a strange, fluid gait that was neither fully human nor fully ape-like. The creature paused at the edge of the trail, turned its head toward the camera, and then approached. Each image showed the Bigfoot getting closer until finally the creature was standing less than three feet from the lens.

The detail in these close-up images was extraordinary. I could see individual hairs in the Bigfoot’s coat, which appeared to be a mix of dark brown and black. Its hands were enormous with thick fingers and what looked like dark nails or claws. But it was the face that made me set down my laptop and step out of the truck to catch my breath.

Chapter 8: The Gaze

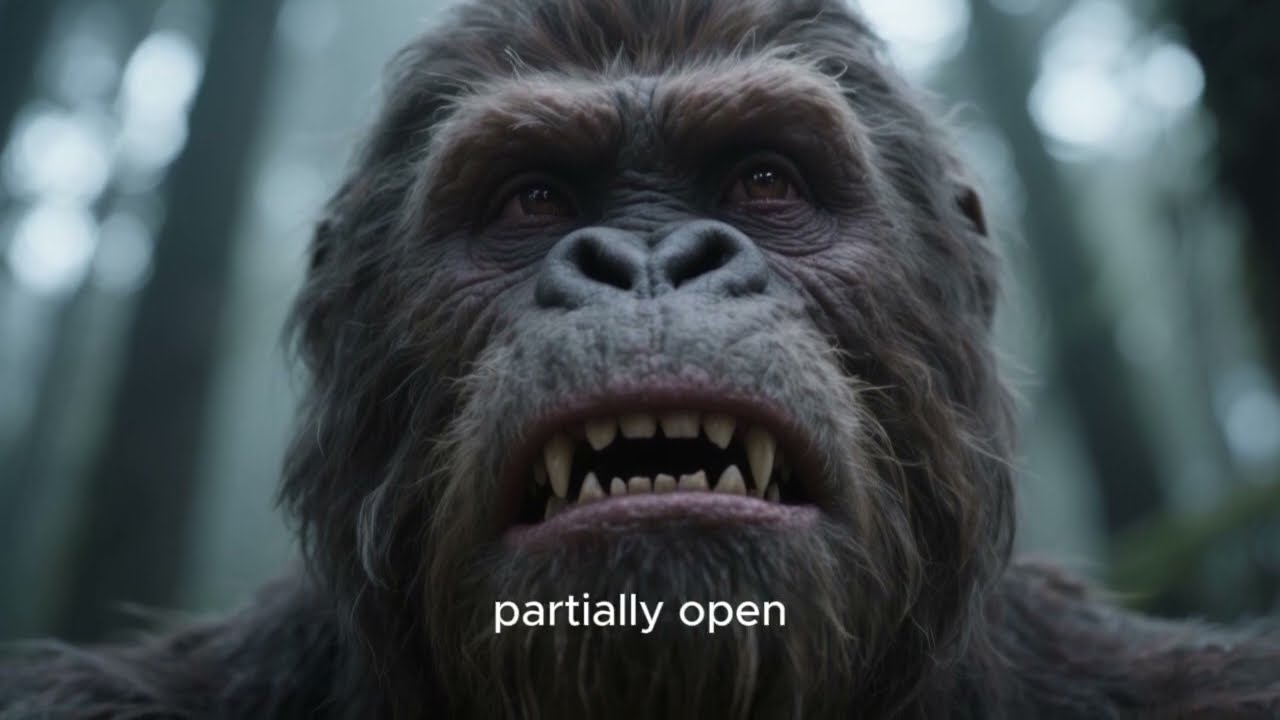

The Bigfoot’s face was not what I expected. Based on famous footage and eyewitness descriptions, I’d always imagined Bigfoot creatures as having ape-like features: flat noses, heavy brow ridges, maybe a sagittal crest like a gorilla. This Bigfoot had those features. But there was something else, something that made my chest tighten with an emotion I couldn’t quite name.

The eyes were large and dark, set deep beneath a prominent brow. But they weren’t the dead, vacant eyes of an animal. There was intelligence there, awareness. The Bigfoot was looking directly into the camera lens, and through the images, I could almost feel the weight of that gaze. The creature knew it was being photographed. It understood what the camera was and what it did.

Its expression was difficult to read, but it seemed almost sad, or maybe curious. The creature’s mouth was partially open, revealing large teeth, but the overall posture wasn’t aggressive. The Bigfoot just stood there, inches from the lens, staring into the camera as if trying to communicate something.

I spent hours examining those facial images, zooming in on different features, trying to understand what I was seeing. The Bigfoot’s skin was visible in patches where the hair was thin—around the eyes, on the nose, parts of the cheeks. The skin appeared dark, almost black, with a texture that looked weathered and tough, not like human skin, which is relatively smooth and delicate, but more like leather that had been exposed to the elements for years.

What struck me most was how human some of the features appeared: the shape of the eyes, the way the Bigfoot’s brow furrowed slightly, creating an expression that looked almost thoughtful. This wasn’t just an animal captured on camera. This was something else, something that existed in the space between human and beast.

Chapter 9: The Test

The close-up sequence lasted for 17 images. Then, the Bigfoot stepped back, turned, and walked away into the darkness. The creature disappeared from frame and didn’t return for another five days.

After that second encounter, the pattern changed. The Bigfoot began visiting the camera almost every night. Sometimes the creature would simply pass through the frame, barely triggering a few images. Other times, it would stop and examine the camera, tilting its head as if trying to understand the device’s purpose.

On day 28, the Bigfoot did something that made me question everything I thought I knew about these creatures. The timestamp showed 4:23 a.m. The Bigfoot approached the camera and reached out with one massive hand. The creature’s fingers moved over the camera housing, exploring it carefully. Then, it gripped the sides of the camera and lifted it slightly, testing its attachment to the tree. The creature wasn’t trying to destroy it. The Bigfoot was examining it, studying how it was mounted.

In the next image, the Bigfoot had rotated the camera, angling it away from the trail and pointing it toward the forest. The creature held this position for several seconds, during which the camera captured nothing but darkness and tree trunks. Then, the Bigfoot carefully rotated the camera back to its original position, released it, and stepped away. The creature stood there for a moment longer, as if waiting to see if the camera would react, then disappeared into the night.

Chapter 10: The Family

Over the next few days, the Bigfoot’s interactions with the camera became more complex. On day 30, the creature brought objects into frame: rocks, sticks, what looked like animal bones. The Bigfoot would place these items in front of the camera lens, step back, wait for the flash, then remove them, and replace them with different objects. It was systematic, deliberate. The creature was testing the camera’s response to different stimuli.

One sequence showed the Bigfoot bringing a large piece of bark and holding it up between the camera and the forest background. The creature moved the bark slowly from side to side like someone waving a flag. After each movement, the Bigfoot would pause as if waiting for feedback. When none came, the creature dropped the bark and moved closer to the camera, peering directly into the lens with what I can only describe as frustration.

The activity continued to escalate. On day 32, multiple Bigfoot creatures appeared in the footage. The images showed what looked like a family group: one large Bigfoot that I assumed was an adult, accompanied by two smaller creatures that were clearly juveniles. The young Bigfoot creatures stayed close to the adult, occasionally reaching out to touch the larger creature’s hand or leg.

The family group moved through the area slowly, pausing frequently as if the adult Bigfoot was teaching the juveniles something. The juvenile Bigfoot creatures were fascinating to observe. They moved with less confidence than the adult, occasionally stumbling over roots or pausing to examine interesting objects on the ground. One of the young Bigfoot creatures picked up a pinecone and brought it to the adult, holding it up as if presenting a gift or asking a question. The adult Bigfoot took the pinecone, examined it briefly, then handed it back to the juvenile. This exchange repeated with several different objects: an interesting rock, a piece of moss, a bird feather.

When they reached the camera, the adult Bigfoot stopped and gestured toward the device. The two juvenile Bigfoot creatures approached cautiously, sniffing at the camera housing and reaching out to touch it with their smaller hands. The adult Bigfoot watched patiently, never interfering as the young creatures explored. After several minutes, the adult Bigfoot made a sound. The camera didn’t capture audio, but I could see the creature’s mouth opening and its chest expanding, and the juveniles immediately moved away from the camera. The family group continued down the trail and out of frame.

This sequence convinced me that I was dealing with something far more sophisticated than a simple animal. The adult Bigfoot’s behavior suggested not just intelligence, but culture. The creature was teaching its young about the camera, showing them what it was and how to interact with it. This was learned behavior being passed from one generation to the next.

Chapter 11: The Warning

On day 37, something changed. The timestamp showed 9:43 p.m. when a single Bigfoot entered the frame. This creature was larger than any I’d seen in previous footage—easily eight and a half feet tall with a massive barrel chest and shoulders that seemed impossibly broad.

The Bigfoot moved with deliberate purpose, approaching the camera directly. When the creature reached the camera, it didn’t examine it or manipulate it. Instead, it grabbed the tree trunk just below where the camera was mounted and shook it violently. The image blurred as the camera rattled in its housing. The shaking lasted for approximately ten seconds during which the Bigfoot’s face remained visible, teeth bared, eyes narrowed in what could only be described as anger.

When the shaking stopped, the Bigfoot released the tree and stepped back. The creature stared into the camera lens for a long moment, then reached down and picked up something from the ground. As the Bigfoot lifted its arm, I could see what the creature was holding—a large rock, probably fifteen or twenty pounds. The Bigfoot raised the rock above its head, clearly preparing to smash the camera. But the Bigfoot didn’t throw it. The creature held the rock there, arm extended, for what the timestamp showed was nearly thirty seconds. Then the Bigfoot lowered the rock, dropped it at the base of the tree, and walked away.

The message was clear. The creature could destroy the camera anytime it wanted, but was choosing not to—for now.

Chapter 12: The Mirror

On day 42, just four days before I retrieved the camera, something happened that I still can’t fully explain. The timestamp showed 3:17 a.m. A large Bigfoot approached the camera and stopped directly in front of it. The creature reached into the darkness beside the trail and pulled something into frame.

It took me a moment to process what I was seeing. The Bigfoot was holding another trail camera. The device was identical to mine—same model, same manufacturer. The Bigfoot held it up to my camera, positioning the two devices lens to lens as if making them face each other. The creature held this position for three full images, then carefully placed the foreign camera on the ground in front of mine, arranging it so both lenses pointed at the same spot on the trail.

The Bigfoot stepped back, looked at the arrangement, and then did something that sent chills down my spine. The creature reached up with one massive hand, and covered the lens of my camera, blocking the view completely. The next 17 images showed nothing but darkness and the texture of the Bigfoot’s palm. When the creature finally removed its hand and walked away, the second camera was gone. The Bigfoot had taken it.

Chapter 13: The Reflection

I sat in my truck for hours going through the footage again and again. The implications were staggering. The Bigfoot creatures weren’t just aware of the camera. They understood it. They understood that it was observing them, recording them, and more than that, they seemed to understand that cameras existed elsewhere, that other cameras were being used by humans to monitor the forest.

But it was the final gesture, covering the lens, that troubled me most. That wasn’t random behavior. The Bigfoot wasn’t just blocking the camera temporarily. The creature was making a statement: I can see you seeing me, and I can choose when you see me.

I decided to conduct additional research before making any decisions. I contacted other wildlife photographers I trusted and asked if they’d ever captured similar footage. Most hadn’t, but three colleagues admitted to having trail camera images that showed unusual figures, large bipedal creatures that didn’t match any known animal.

One photographer in Northern California had footage of a Bigfoot examining a camera much like mine had been examined. She’d never shared the images because she feared being ridiculed. Another photographer working in British Columbia sent me a remarkable sequence of images: his trail camera had captured a Bigfoot carrying what appeared to be a young deer carcass. The creature walked upright despite the burden, moving with surprising grace through difficult terrain. What made the footage particularly interesting was that the Bigfoot stopped directly in front of the camera, set down the carcass, and spent several minutes examining the device. The creature even reached out and touched the lens, leaving a clear handprint on the protective cover.

The third photographer, working in the Olympic Peninsula, had multiple cameras that had been deliberately repositioned by something. His cameras were originally mounted to capture elk migration patterns, but over the course of a single night, three cameras were removed from their trees and relocated to new positions. The cameras hadn’t been damaged. They’d been carefully detached and remounted at different heights and angles, all pointing toward a central clearing. When he retrieved the footage, he found images of a group of Bigfoot creatures gathering in that clearing, almost as if they’d arranged the cameras to document their own meeting.

Chapter 14: The Package

About three months after my last trip to the ravine, I received a package of my own. There was no return address, just my name and address written in surprisingly neat handwriting. Inside was a small memory card and a note written on bark—actual tree bark with text burned into the surface using what looked like a hot wire or tool.

The note said, “Look at the images. Then look closer. The truth is in the reflection.”

I inserted the memory card into my computer and found a single folder containing twenty images. They were all photographs of trail cameras—dozens of different cameras in various locations. Some were mounted on trees like mine. Others were positioned on fence posts, rocks, or artificial structures. The images showed cameras from different manufacturers, different models, different configurations. But they all had one thing in common: they were all clearly visible, easy to find, positioned in obvious locations.

Then I looked closer, as the note instructed. I zoomed in on the lenses of the cameras in the photographs and that’s when I saw it. In the reflection on each lens was another camera. Someone or something had photographed these trail cameras using another camera.

Chapter 15: The Realization

I went back to my original footage from camera 17 and examined the clearest close-up images of the Bigfoot’s face. I enhanced the resolution and zoomed in on the creature’s eyes. There, in the reflection of the Bigfoot’s cornea, visible in just a few frames, was the unmistakable shape of a camera. Not my camera—something else. Something the Bigfoot was holding or wearing.

The implication hit me like a physical blow. The Bigfoot creatures weren’t just aware of cameras. They were using cameras. They’d been photographing us, documenting us, just as we’d been trying to document them. Every trail camera we positioned in the forest, every motion sensor we hid on game trails—the Bigfoot knew about them, and the creatures had been watching us watch them.

That’s why they brought that second camera to mine and positioned them lens to lens. The Bigfoot wasn’t just demonstrating awareness. The creature was showing me that they have their own surveillance network, their own system for monitoring human activity in their territory. We thought we were the observers. All along, we were the observed.

Chapter 16: The Dilemma

I’ve spent months trying to process this revelation. The idea that Bigfoot creatures have adapted not just to avoid our technology, but to use it against us is simultaneously fascinating and terrifying. It suggests a level of technological sophistication that I never imagined possible for a supposedly primitive species.

Where did they get the cameras? Did they steal them from other locations? Did they somehow acquire them from human sources? Can they operate them, or do they just position them and leave them to record automatically?

I began analyzing the twenty images more systematically, creating a database of the cameras shown. I identified cameras from at least seven different manufacturers spanning models released over the past fifteen years. Some were current production models. Others had been discontinued for years. The geographic distribution was also telling—based on visible vegetation and terrain features, the cameras appeared to be from locations across Washington, Oregon, Northern California, and British Columbia.

This meant the Bigfoot surveillance network was extensive. The creatures weren’t just monitoring a single region or mountain range. They had systematic coverage across a significant portion of the Pacific Northwest. And if they were photographing trail cameras, they were likely tracking the humans who placed those cameras. They were learning our patterns, our methods, our technologies.

Chapter 17: The Implications

What else have they been doing that we don’t know about? If the Bigfoot creatures can use trail cameras, what other technology have they mastered? Are they monitoring us in other ways? Do they have lookouts watching human settlements? Have they been studying our behavior, our routines, our weaknesses?

The scariest part is that we have no idea how many of them there are or how organized they might be. My footage showed family groups, multiple individuals moving through the same territory, coordinated behavior that suggested communication and planning. But that was just one small area in one mountain range. How many other groups exist? How far does their network extend?

I tried to trace the origin of the package. The postmark was from Seattle, but that meant nothing. It could have been mailed from anywhere and sent through an intermediary. The handwriting on the address was careful and deliberate, suggesting someone educated. But who was there? A human intermediary working with the Bigfoot creatures, or had someone else discovered similar evidence and decided to share it anonymously?

The bark note itself was fascinating. The text had been burned into the surface with remarkable precision. Each letter properly formed and evenly spaced. Creating text like that would require patience, steady hands, and probably some kind of hot tool or wire. The Bigfoot creatures had the patience and steady hands. I’d seen that in the way they manipulated my camera. But did they have the tools? Or again, was there a human collaborator?

Chapter 18: The Choice

I haven’t returned to that ravine since receiving the package. Part of me wants to go back to try to establish some kind of communication or understanding with the Bigfoot creatures there, but a larger part of me worries about what might happen if I push too hard. The creatures clearly have boundaries. They’ve demonstrated both their awareness and their capability. The rock that could have destroyed my camera but was lowered instead. The lens covered gently rather than violently. These were warnings, not threats, but they were warnings nonetheless.

I still work as a wildlife photographer, but my perspective has changed fundamentally. Every time I position a trail camera, I wonder if a Bigfoot will find it. Every time I review footage, I look for reflections in lenses and eyes, searching for evidence of other observers. And I’ve started being more careful about where I place cameras, thinking not just about what I want to document, but about how my presence and technology might impact the creatures I’m studying.

The most difficult part is the isolation. I can’t talk about this openly. The few colleagues I’ve shared the complete story with have warned me against going public. They’ve seen what happens to people who claim to have extraordinary evidence of Bigfoot: the ridicule, the accusations of fraud, the career damage. Even with clear photographs and video, there’s always doubt. And in this case, the implications are so enormous that most people would prefer to believe I’m lying rather than accept the truth.

Chapter 19: The Final Reflection

I’ve thought about what public disclosure would mean. The immediate response would probably be skepticism mixed with fascination. Some people would demand to see all the footage. Others would dismiss it as an elaborate hoax regardless of the evidence. Eventually, if the footage was accepted as genuine, the conversation would shift to what should be done: protect the Bigfoot creatures as an endangered species, study them scientifically, leave them alone. Each option carries its own problems.

There’s also the question of what the Bigfoot creatures themselves want. They’ve made it clear they’re aware of us, and capable of interaction. Yet, they choose to remain hidden. The deliberate nature of their camera engagement suggests they’re testing us, learning about us, but not yet ready for open contact. Perhaps they’re waiting for something. Perhaps they’re preparing for an inevitable future when our two species will have to acknowledge each other.

But I know what I saw. I know what my cameras captured. And I know that somewhere in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, there are creatures that are far more intelligent and capable than we’ve ever imagined. The Bigfoot creatures are not just surviving in the modern world. They’re adapting to it, learning from it, using it to their advantage.

The question that keeps me up at night is what they’ll do with that advantage.

Epilogue: The Watchers

So far, their interaction with humans has been limited to curiosity and warning. But what happens when their territory shrinks further? What happens when development and climate change push them into closer contact with human populations? Will they continue to hide, or will they make their presence known in ways we can’t ignore?

I look at the close-up images of that scarred Bigfoot’s face often. I’ve printed the clearest one and keep it in my office. Sometimes I stare at those intelligent eyes and try to imagine what the creature was thinking when it looked into my camera. Was the Bigfoot curious, amused, concerned? Did the creature understand that by allowing itself to be photographed so clearly, it was changing the relationship between our species?

Over time, I’ve developed theories about what the Bigfoot’s facial expressions might mean. The slight forward lean when examining the camera suggests focused attention and curiosity. The open mouth in some frames could indicate surprise or possibly communication. Many primates make vocalizations with their mouths partially open. The direct eye contact maintained across multiple images speaks to confidence and perhaps even challenge. In the animal kingdom, sustained eye contact can be threatening, but it can also be a form of social engagement.

I’ve compared my footage to documented behaviors of other great apes—gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans. There are similarities, particularly in the way the Bigfoot uses its hands to manipulate objects and the manner in which the adult creature interacts with juveniles. But there are also significant differences. The Bigfoot’s level of technological understanding far exceeds anything documented in wild apes. Even chimpanzees, our closest relatives, don’t demonstrate the kind of abstract thinking required to understand what a camera is and how it functions.

The creatures aren’t just solving immediate problems. They’re thinking about systems, understanding cause and effect across time, and planning for future interactions. The way the Bigfoot positioned that second camera lens to lens with mine showed an understanding not just of what cameras do, but of symbolic representation. The Bigfoot was making a statement: Your cameras see us. Our camera sees you.

I keep the memory cards locked in a safe. I keep the photographs encrypted on secure drives. And I keep watching the forests, wondering if somewhere out there, a Bigfoot is watching back—not with fear or hostility, but with the same curiosity that drove me to place that first trail camera. We’re both trying to understand each other. We’re both trying to figure out how to share this world.

Maybe someday I’ll go public with everything. Maybe someday the Bigfoot creatures will decide to reveal themselves on their own terms. Or maybe we’ll continue this strange dance of mutual observation. Always aware of each other, but never quite meeting face to face.

Whatever happens, I know one thing for certain: the next time you position a trail camera in the wilderness, take a moment to look around. Look at the trees. Look at the shadows. And ask yourself, what if something is looking back? What if the observers we’re trying to document are observing us just as carefully?

Because somewhere in the forests of North America, there are creatures that know we’re watching. The Bigfoot creatures have seen our cameras, examined our technology, and made their own calculations about how to respond. They’re intelligent. They’re organized, and they’re still out there moving through the darkness just beyond the range of our lights, choosing what we see and what remains hidden.

That’s the shocking thing that happened after my camera caught a Bigfoot’s face. I didn’t just capture evidence of an unknown species. I discovered that the unknown species has been capturing evidence of us. We’re not the only ones documenting life in the wilderness. We’re not the only ones trying to understand the world around us. And we’re definitely not the only ones using cameras.

The Bigfoot creatures are watching. They’ve always been watching. And now that they’ve shown me what they can do, I can’t help but wonder—what else don’t we know? What else are they capable of? And what will they do when they decide they’ve seen enough?

I’ll end this account with the same advice that mysterious note gave me: Look at the images, then look closer. The truth is in the reflection. Because sometimes what we’re looking for has been looking back at us the entire time.