Midnight Predator: Appalachian Farmer Catches a Massive Bigfoot Raiding His Goat Pen

THREE KNOCKS IN THE SNOW

A Dr. Kenny Price account — Twisp, Washington (2014

.

Chapter 1 — The Scientist Who Didn’t Sleep

My name is Dr. Kenny Price. I’m forty-six now, living in a neat townhouse where the loudest wild thing is a neighbor’s dog and the only wind comes through alleyways between buildings. But what I’m about to tell you happened in late January of 2014, up near Twisp on the eastern side of the Cascades, during a deep-snow year when the pine air was so cold it felt sharp enough to cut your teeth. I shouldn’t be telling this—because it stains everything I’ve built my career on—but it has been years, and I don’t really sleep anyway. Back then I was thirty-four, a contract wildlife biologist wintering alone in a Forest Service cabin, tracking snowpack, wolverine sign, and camera traps—real work, measurable work, the kind that lives in spreadsheets and peer-reviewed journals. My nights were the same dull hymn: baseboard heater ticking, the refrigerator’s low rumble, the faint wind scraping at the eaves, and the porch light throwing a yellow cone onto blue snow. Boredom is supposed to be safe. Loneliness is supposed to be manageable.

Locals in town loved to test the “city scientist.” At the gas station they’d mention mountain lions and ghosts, then grin and toss in Bigfoot like a hook to see if I’d bite. I hated the word. I still do. I’d smile politely, stir powdered creamer into cheap coffee, and file it all away as folklore—same drawer as UFOs and miracle diets. Still, there were nights when the cabin wood popped and the trees leaned in like listeners, and I caught myself checking the deadbolt twice. I’d hear something shift in the snow—something heavy—and then nothing. Silence so complete it felt staged, like the forest had decided to stop breathing until I stopped moving.

Chapter 2 — Hank’s Diner and the Rule of Three

January 27th, Hank’s Diner in Twisp at 5:42 p.m. is the kind of place you can describe with sound alone: fluorescent lights buzzing, country radio hissing under a vent fan, snow melting off boots onto cracked linoleum, forks on plates, a kid’s tablet blaring cartoons too loud in the corner. I was at the counter scribbling notes about a wolverine track line when Ray Haskins slid onto the stool beside me. Ray was a trapper in his late fifties with a beard like steel wool and that permanent smell of wood smoke and wet dog. He asked if I was staying up at mile fourteen. I said yes—the Forest Service cabin. He snorted like the word cabin tasted funny.

“Boys up there last winter said they heard Bigfoot,” he said, blowing on his coffee. “Knocks in the trees. You hear any of that crap yet?” I laughed too quickly, the way you do when you want a conversation to die before it grows teeth. “Just the usual. Wind in the trees.” Ray didn’t laugh back. He watched me longer than was polite, like he was deciding whether I was stubborn or simply young. Then he said something that followed me back up the mountain and into the dark like a shadow that refused to detach.

“Wind don’t knock three times, son.”

Driving back in the blue-gray dusk, snowflakes spinning in the headlights, I told myself Ray was just entertaining himself. But my grip tightened on the steering wheel. Every time my tires crunched over icy gravel, I heard an echo of those words. Wind doesn’t knock three times. When I pulled into the cabin’s clearing, my hand shook just slightly when I flipped on the porch light and watched its yellow circle spill across empty snow. Empty, I told myself. Always empty.

Chapter 3 — The Shape in the Ditch

January 30th began with routine—the only religion I trusted then. The coffee maker dripping, AM radio news fighting through static, ice popping in the gutters, the sky shifting from black to a dull cold blue. I pulled on frozen boots, grabbed snowshoes, poles clacking against the doorframe, and set out to check two snow courses and swap batteries on a remote camera. Just another day of being the only human for miles. I remember standing on the porch for a moment, breath clouding, staring at the ridge line smudged with low cloud. The woods were still like they were listening. I told myself that was poetic nonsense and forced my brain to focus on snow-water equivalent instead.

The storm rolled in earlier than forecast. By midafternoon the valley looked like it was being swallowed by a gray wall, wind worrying treetops into a constant shushing that sounded like distant traffic. My snowshoes hissed over fresh powder as I headed back toward the truck, thighs burning, and the first thing that changed wasn’t what I saw—it was what I smelled. The clean bite of winter picked up something musky and rank, like a wet dog that had lived in the woods its whole life. It came and went with gusts. I told myself it was a buried elk. That happens. That’s normal.

Then I saw the shape in the ditch, half covered in drifted snow. Not an elk shape. Too long. Too much of it. The light was going flat and blue, snowflakes racing through my headlamp beam like ash. “Probably a black bear,” I muttered, saying it out loud because loud made it safer. Bears were a category I understood. But the closer I got, the less it looked like any bear I’d ever seen. No obvious neck. No snout. Just a mound of frozen, matted fur and a limb sticking up at the wrong angle. An arm, my mind insisted, and I hated it for choosing that word. I could see the dark mass of a hand or paw—fingers or claws splayed.

The wind roared through the trees and then dropped, leaving everything unnaturally quiet. My ears rang in the sudden silence. Bigfoot popped into my head against my will, like a reflex. I actually shook my head as if I could physically dislodge the thought. “I don’t believe in that stuff,” I said, quieter now, like I was afraid something might hear me confess it. Snow was already building over the body, smoothing it away. If I left, it would be buried by morning, gone into white the way the mountains like to erase inconvenient things. I looked back down the empty road, then down at the impossible shape, and knew that if I walked away, I’d never sleep again.

Chapter 4 — Dragging Evidence into the Light

You could film the next hour in one long miserable take: me looping a sled rope around that frozen limb, digging my heels into powder, breath coming in ragged bursts that fogged the air in front of my headlamp. Wind pushed at my back like it was trying to hurry me—or push me away. The body was heavier than anything its size should have been. Under the ice in the fur, there was a density that didn’t match bear or moose, a compactness that made my arms shake with effort. Even through thick gloves, I remember the fur’s texture—coarse, stiff, like dragging a hand across an old rug abandoned in a barn. Every few minutes the smell hit again: wet fur, old sweat, and a metallic tang like blood and rusted iron.

Online movie streaming services

I kept telling myself dead like a mantra. Dead is safe. Dead doesn’t move. Dead is just data. Halfway back I had to stop and lean on the sled handle, heart pounding loud enough to hear over the wind. I tried to joke with the empty forest because jokes are how you keep panic from becoming prayer. “Ray’s going to laugh his ass off when I tell him I dragged home a frozen Bigfoot.” The word sounded stupid in my mouth, like something childish. The scientific part of my brain recoiled. But I didn’t turn around. The cabin porch light was a faint gold dot in the distance, fragile against the storm like a candle cupped in two hands.

When I finally hauled the body into the cabin’s mudroom, the place felt too small, too human. Meltwater dripped off the fur onto the rubber mat, pattering like a slow leak. The refrigerator hummed louder than usual—or maybe I was just more aware of any sound that proved the world was still behaving normally. The baseboard heater clicked on and made the air smell like dust. I shut the interior door and stood alone in that uninsulated space under a bare bulb that turned everything the color of old bone. My hand shook when I reached out to touch the fur again. Stiff with ice, yes, but beneath it there was give—meat, not a solid frozen log.

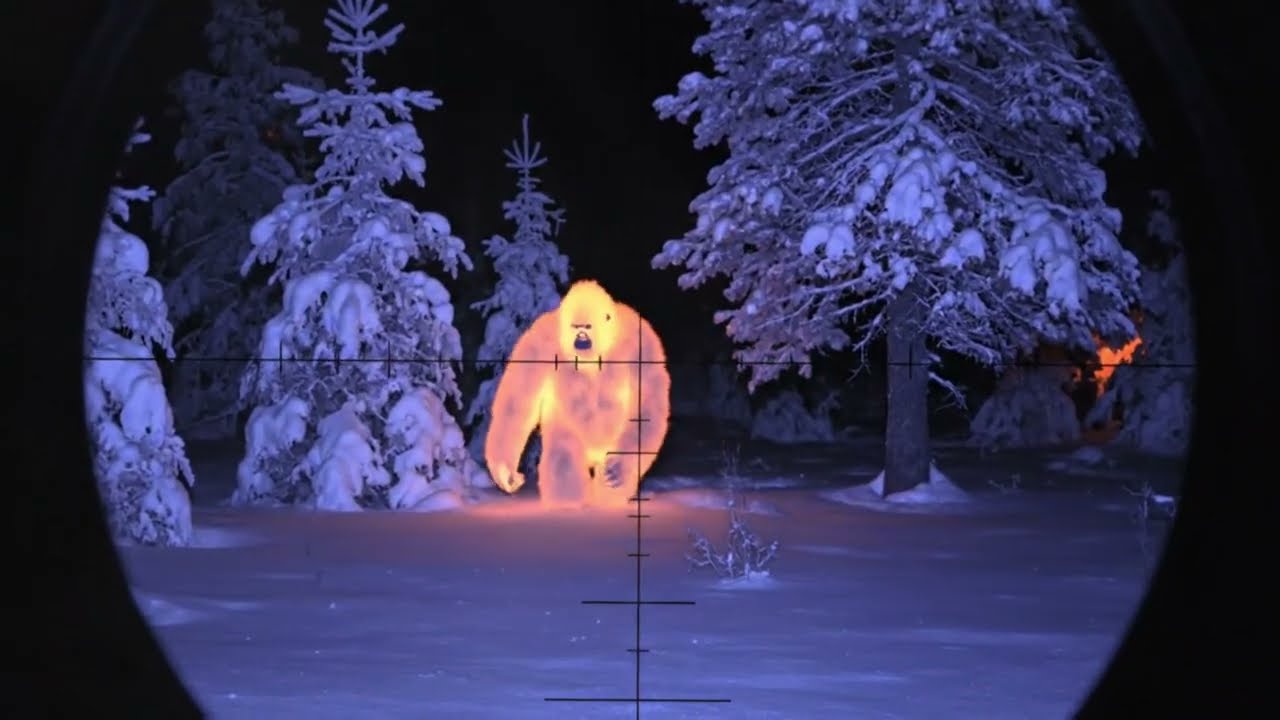

“This is insane,” I whispered. “I can’t have a Bigfoot in my mudroom.” I told myself I’d call the sheriff in the morning, or Fish and Wildlife, someone official. Let them deal with the explanation, the paperwork, the reality. Professional habit kicked in anyway: document, then think. I set up my old field camera on a tripod, pointed it toward the mass on the floor. The little red recording light blinked in the dimness like a tired eye. I turned out the light, closed the inner door quickly, and listened from the kitchen to the quiet thump of snow sliding off the roof, repeating my mantra until my tongue felt numb: dead is dead.

Chapter 5 — The Sound That Shouldn’t Exist

Morning came pale and weak through frosted windows, the storm blown out as abruptly as it had arrived. The cabin smelled like coffee and ethanol and that heavier animal musk bleeding in from the mudroom. I’d slept maybe an hour. Every time the cabin creaked, I snapped awake. I checked the camera feed—no motion, just my own pulse roaring in my ears. I told myself I was being ridiculous. This was the opportunity of a lifetime: an unknown specimen, a rare event, a mystery with a body attached. My job was to examine, measure, take samples, not sit at the table staring at the mudroom door like a kid afraid of monsters.

“I don’t believe in Bigfoot,” I said firmly as I laid out instruments on a towel: scalpel, measuring tape, sample vials, pressure cuff. The word sounded hollow now, as if the last twenty-four hours had worn some disbelief off it. I opened the door and the cold hit first, then the smell—stronger, sour, wild, mixing with clean winter air leaking around the frame. The body hadn’t changed. Same twisted limb, same matted fur. Dead, I told myself, twice, under my breath. Up close, the skin visible between fur looked grayish and slack.

I knelt. The camera’s battery light blinked yellow. I approached from the side, careful, like caution could rewrite reality into something manageable. I wrapped the pressure cuff around the thick forearm, avoiding looking too closely at the hand. The rubber felt stupidly clinical against whatever this was. I pumped the bulb until the cuff tightened.

Then the sound came—low, wet, unmistakable: an inhale.

I froze mid-squeeze. For a second, my mind tried to rescue me with excuses—maybe it was me, maybe an echo, maybe a trick of the cabin. I held my breath. On the audio, you’d hear the room go nearly silent, like even the refrigerator was listening. Then it happened again, longer, dragging, like something that had been underwater too long finally reaching air. The cuff twitched in my hand—a millimeter, maybe less—and the needle on the analog gauge jumped.

“No,” I heard myself say, and it came out between a word and a plea. “You’re dead. You’re frozen. You can’t be—” Bigfoot stuck in my throat, and I hated how it made the moment feel like a campfire story grafted onto my real life. Under my glove, the skin felt different—less like cold meat, more like cold rubber that had once been warmed. Its chest shifted under the fur, not a full rise, just a tremor, like whatever lived inside that body was testing the idea of breathing again. My vision went grainy at the edges. Every trained instinct screamed at me to run, lock the door, bury the footage, never say the word again. Every scientific instinct told me to stay and observe.

I did neither. I knelt there shaking while the recorder caught the sound of something impossible remembering how to breathe.

Chapter 6 — The Door Between Us

Time got strange. Seconds stretched and then snapped tight. The ambient noise of the cabin seemed to dim, as if someone was slowly turning the world’s volume down. No radio. No heater click. Just the drip of meltwater and the occasional ragged inhale from the floor. I realized my hand was still on the cuff bulb. I slid my fingers beneath the cuff where a radial artery would be on a human. Nothing. Then—faint as a memory—two fluttering beats, a pause, three beats, and nothing again. I yanked my hand back like I’d been burned and stumbled hard onto the floor.

My brain began listing possibilities like a man reading prayers from a manual. Hypothermia. Hallucination. Concussion. Carbon monoxide. Anything but the truth sitting in my mudroom. I heard myself laugh—high and breathless, with no humor. The thing answered with a sound that wasn’t a growl and wasn’t anything I’d heard from bears or elk: low, confused, almost pained. That was the worst part, the confusion, because it made it feel less like a predator and more like a trapped someone waking in the wrong place.

I bolted. I slammed the interior door and threw the deadbolt like it mattered. In the cabin, the light felt wrong—too bright, too clinical. The radio had fallen into pure static. The refrigerator hummed like a nervous insect. I stood in the middle of the room, listening, half convinced I’d imagined everything until I heard movement—heavy, dragging, the scrape of a large body shifting its weight on the mudroom floor. Then a low sound halfway between a moan and a cough.

Guilt hit me so hard it felt physical. Not guilt for panicking—guilt like I’d broken into someone’s grave and they’d woken up trapped. And then came the sound that still tightens my throat when I remember it: from the other side of the mudroom door, three slow knocks. Not frantic pounding. Not rage. Three measured, evenly spaced knocks, like someone politely asking to be let out. The knocks didn’t repeat. Just those three, perfectly controlled.

“Bigfoot,” I whispered, not dismissing it now but naming whoever was on the other side like you’d say a person’s name. “You’re awake, aren’t you?” A long shuddering exhale answered, and the smell of wet fur and iron seeped under the threshold into the warm cabin air.

Chapter 7 — The Release and the Shoebox

I stepped out into the snow in flannel and jeans, no coat, the cold slapping sense back into me. The world had gone quiet—no wind, only a distant woodpecker tapping somewhere upslope and the tiny ticking of ice in branches. I circled to the mudroom’s exterior door, the one with a padlock that was mostly for show. My fingers fumbled with it, numb. Inside, something shifted again—slow and careful, not threatening, just trapped and hurting in a space the size of a closet. I thought about calling Fish and Wildlife, about what would happen next: trucks, cameras, sedatives, cages, maybe an autopsy if the shock finished what the cold started. And I thought about those three polite knocks.

“I’m so sorry,” I whispered, and I wasn’t sure who I was apologizing to—my training, my career, or the being I’d dragged home like a trophy. Then I slid the padlock free. My hand shook on the knob. “Okay,” I said, loud enough to carry through the wood. “Door’s open. You can go. No one needs to see you. No one ever has to know. Just go.” I stepped back, heart hammering so hard I could hear it over my own breathing.

The latch clicked from the inside. The door opened. I didn’t look straight at what came out—not because I wanted to preserve denial, but because my eyes couldn’t handle the full weight of it. I saw impressions instead: a mass blotting out the doorway, fur dark against snow, breath steaming in ragged clouds. A hand brushed the frame—fingertips thick and blunt—leaving smears of meltwater on the wood. It didn’t rush me. It moved past, limping, each step carrying a shudder through its frame. As it passed between me and the trees, the smell washed over me again—wet fur, iron, and underneath it, sap and earth and pine, the forest’s own signature.

At the treeline, it folded into shadows between trunks like it had never been on my floor. It paused once, one hand resting on a low branch, snow-laden limb dipping. The world held its breath. Then it was gone.

Four days later, the cabin sounded different at night—or maybe I just heard it differently. I scrubbed the mudroom until the rubber mat squeaked, but the smell lingered in seams. I found fur in the door jamb, in my boot tread, wedged in a crack in the floorboard. I watched the recording once, alone, volume low. You can hear everything: the cuff pump, my fast breathing, the drip of meltwater, and then that wet inhale that shouldn’t exist. The moment I say Bigfoot with terror and recognition. The three knocks from behind the door. I transferred the clip to an old phone with a cracked screen, wiped the camera card clean, and buried the phone in a shoebox under field notes and sample jars. Officially, in my report, an avalanche damaged equipment and cut the season short. Nothing more.

It’s been almost ten years. I teach undergrads now and say the line you’re supposed to say: there’s no credible scientific evidence for Bigfoot. Most nights, I almost believe myself. Then the city goes quiet and some distant sound thumps—an old building settling, a neighbor’s door, a truck backfiring far away—and my body tenses like I’m back in that cabin, listening to a door that once separated me from something that breathed when it shouldn’t have. On the worst nights I take down the shoebox and rest my hand on the lid without opening it, remembering the weight of the cuff bulb in my palm, the flutter under cold skin, and the smell of wet fur and iron threading into cheap coffee. I say the word differently now when I have to—softer, like a name, not an idea.

I still don’t know if I did the right thing. I only know this: something that shouldn’t have breathed, breathed. Something that shouldn’t have knocked, knocked. And sometimes, muffled through years and drywall, I swear I hear three slow knocks on a door that isn’t there anymore.