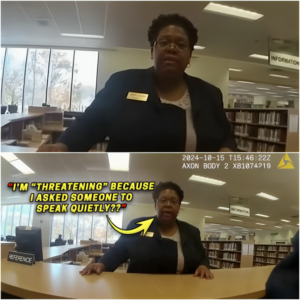

Officer Handcuffs Head Librarian After Bogus Accusation – Career Destroyed After $320K Lawsuit

.

.

Shelves, Silence, and a $320,000 Lesson

1. “Step Outside”

“Ma’am, we received a complaint about you being aggressive and threatening.”

The words floated across the reference desk like something out of a bad TV drama.

Professor Camille Hart, Head Librarian of the Easton City Public Library, didn’t even look up at first. She finished typing the last term into the catalog search bar for the man standing in front of her, clicked “print” on the list of call numbers, and slid the paper toward him with a small, polite smile.

“There you go, Mr. Diaz,” she said. “They’ll be on the second floor, aisle 7B.”

Only then did she turn to the uniformed officer standing three feet away.

“Threatening,” she repeated calmly. “Because I asked someone to lower their voice? This is a library.”

Officer Ethan Boyd shifted his weight, hand resting near his duty belt in that automatic way cops often had, thumb hooked casually by his holster. He was mid-thirties, white, solidly built. He looked like a man who expected his words to be taken seriously.

“The caller said you were hostile and made them feel unsafe,” he said.

The library hummed quietly around them. The soft thump of books closing, the faint clack of keyboards, the distant squeal of a child from the children’s wing, quickly hushed. Outside, late October sunlight slanted through tall windows, making squares of light on the old hardwood floors.

“I was doing my job,” Camille said. “I’m the head librarian here.”

“Sure,” Boyd replied, the word flattening in his mouth. “Now, can you step outside so we can talk about this?”

The patron Mr. Diaz hovered uncertainly, eyes flicking between them.

“It’s fine,” Camille told him. “You can go ahead. The books are where I said.”

He hesitated, then nodded and walked away, glancing back once.

“Officer,” Camille said, folding her hands lightly on the desk, “why do I need to step outside? I’m working. I’m the only librarian on reference right now. If you have a question, you can ask it here.”

“This is an official response to a complaint,” Boyd said. “We need to talk without disturbing others.”

“You’re disturbing people more than I am,” Camille said mildly. “But I’m happy to answer your questions right here. I’m not leaving my post unless you’re detaining me.”

He blinked. People who knew their rights always made him blink.

“I’m not saying you’re under arrest,” he said. “We just need to clear this up.”

“Then we can clear it up here,” Camille replied. “Again: I am working. Patrons need me at this desk. You can ask what you like.”

A couple of heads turned at nearby tables now, curious. Camille noticed but didn’t acknowledge them.

She’d been here before. Not with police, but with angry patrons. People who didn’t understand or care that a library was public but not lawless, open but not unlimited. People who thought “customer service” meant “do anything I want.”

She hadn’t expected the police to show up for this one. But it didn’t shock her either.

Almost nothing did anymore.

2. The “Aggressive” Librarian

At forty-eight, Dr. Camille Hart had spent more of her life inside libraries than outside of them.

She’d grown up in Chicago, the daughter of a schoolteacher and a mail carrier. On hot summer days, when her parents were working and the neighborhood felt too tight, she’d ride the bus to the branch library and live there until closing: reading, hiding, growing.

She earned a bachelor’s in history, then a master’s in library and information science, then a second master’s in archival studies for good measure. Later, she completed a PhD in information behavior. For twenty-six years she’d worked in public libraries: shelving, answering reference questions, teaching computer basics to seniors, running literacy programs, eventually moving into management.

For the last ten of those years, she’d been Head Librarian at the Jefferson Avenue Branch, the largest in Easton City.

She was five-foot-seven, with locs pinned neatly at the back of her head, glasses with thin gold frames, and a wardrobe of cardigans and tailored trousers. Her name tag read Dr. C. Hart – Head Librarian in crisp white letters on black plastic.

She was known among staff for three things:

She almost never raised her voice.

She knew regular patrons by name, book taste, and often favorite sports teams.

She enforced the rules. Quietly. Consistently. No matter who you were.

On this particular Tuesday, the after-school rush had filled the main floor. High school students clustered around study tables. College kids hogged computers. A knitting group murmured in a corner. The children’s story hour was winding down behind glass doors.

At 3:20 p.m., four teenagers had bounded in, loud laughter preceding them by several steps. They dropped their backpacks at a table near the windows and started talking as if they were in a cafeteria, not a reading room.

Camille observed for a minute, gauging. Noise was allowed—within reason. But their voices bounced off the high ceilings like rubber balls.

She walked over.

“Hi,” she said, smiling. “Welcome. I’m going to ask you to bring it down a notch, okay? People around you are studying.”

Three of the teens—two boys, one girl—immediately said, “Sorry,” in that sheepish teenage way and ducked their heads.

The fourth, a girl in expensive athleisure, designer crossbody bag and flawless nails, looked Camille up and down with narrowed eyes.

“We weren’t even that loud,” the girl said.

“I appreciate you saying that,” Camille replied, same tone, same smile. “But from here, you are. You’re welcome to stay, just keep your voices low.”

The girl rolled her eyes.

“Whatever.”

They quieted. Camille walked back to the reference desk and resumed helping a patron find zoning regulations.

Five minutes later, Officer Boyd walked in.

3. The Caller

Outside in his patrol car, Boyd had gotten the call from dispatch.

“Unit 12, disturbance at Jefferson Avenue Library. Caller reports aggressive employee. Caller states, quote, ‘She got in my face, yelled at me, made me feel unsafe.’”

“Any weapons mentioned?” Boyd asked.

“Negative,” dispatch answered. “Caller is a juvenile, sixteen. Her mother is on the line. They’re requesting an officer respond.”

“Copy,” he said. “En route.”

It wasn’t the first time he’d responded to a complaint like this. In his eleven years on the job, he’d gone to dozens of “disturbances” that turned out to be arguments over policies: store managers enforcing return rules, school staff enforcing dress codes, restaurant hosts enforcing wait lists.

Usually, the complainant was white. Often, the employee they were complaining about was not.

Boyd didn’t think of himself as racist. He thought of himself as professional. He went where dispatch sent him and made the scene safe.

If he was honest, he did sometimes roll his eyes internally at “these people” on both sides. People with rules. People with complaints. People who called 911 for everything.

But in his mind, callers were upset for a reason. It wasn’t his job to question that too much.

At least, that’s what he told himself.

4. “Am I Being Detained?”

“Ma’am,” Boyd said now, “you’re being uncooperative.”

Camille kept her gaze steady on him.

“I’ve answered your questions,” she said. “I told you exactly what happened. If you want to talk to the girl who called you, she’s right over there.” She tilted her head toward the teen table. “If you want to review security footage, we have cameras covering public areas. Our director can get you access. What I’m not going to do is abandon my job to satisfy a caller who didn’t like being told to follow the rules.”

A library assistant, a young man named Jerome, hovered a few feet away, watching nervously.

Officer Boyd’s jaw tightened.

“You need to understand,” he said, “when an officer gives you a lawful order—”

“Is it lawful?” Camille asked. “What law requires me to leave my workplace when I haven’t committed a crime? You haven’t said I’m detained. You haven’t told me you suspect me of anything specific. You’re responding to a complaint. I’m responding to patrons.”

He hated that word: specific. He heard it all the time at training.

Specific, articulable facts. Probable cause. Reasonable suspicion.

He rarely needed them in calls like this. He showed up. People complied. Paperwork got filed.

“We can handle this the easy way or the hard way,” he said, falling back on a script.

“There’s no ‘way’ to handle,” Camille said. “I asked teenagers to lower their voices. That’s all.”

A man with a laptop had pulled his earbuds out. A mother near the children’s area was watching with a frown. The air felt different now—thin, brittle.

The teen girl in athleisure, the caller, was watching too, arms folded, satisfaction flickering around her mouth.

Camille saw all of it.

She also saw Malik, one of her favorite regulars, an eleven-year-old who came in every day to read graphic novels in a corner, now standing halfway behind a shelf, eyes wide and anxious, watching the officer’s hand near his belt.

She thought of him.

She thought of every kid in this room watching what happened to the Black woman who ran their library when a white girl complained.

“Let me talk to someone in charge,” Boyd said.

“I am someone in charge,” Camille said. “I am the manager of this building. Want my boss? His office is at Headquarters on 4th Street. I can give you his number.”

A security guard approached. Ralph, mid-fifties, Black, had worked at the branch for fifteen years. He wore a navy blazer with “Security” embroidered over his heart.

“Everything okay, Dr. Hart?” he asked.

“Officer Boyd is responding to a complaint about me enforcing our noise policy,” she said. “I’ve explained the situation. He’d like me to step outside. I’ve declined.”

Ralph looked at Boyd steadily. “You want me to call Director Thomas?” he asked.

“That won’t be necessary unless Officer Boyd insists on escalating,” Camille said.

Something in Boyd bristled at the word.

Escalating.

He was the one in uniform. He was supposed to be the de-escalator. That’s what they told him in training. That’s what the posters in the break room said.

Yet here he was being accused of the opposite. In public. In front of an audience. In front of a Black woman with “Doctor” on her name tag and a security guard backing her up.

His ears felt hot.

“Ma’am,” he said, voice hardening, “I’m not going to stand here and argue with you about this.”

“Neither am I,” Camille said. “If you have further questions, you can speak with the city’s Library Director. I’ll write his number down for you.”

She pulled a sticky note toward her, reached for a pen.

“Turn around and put your hands behind your back,” Boyd said.

The pen paused mid-air.

The room seemed to tilt.

“Excuse me?” Camille said.

“You’re under arrest for obstructing an investigation,” he said, words coming faster now that they’d started. “You refused a lawful order to step outside and you’re interfering with my ability to resolve this complaint.”

Ralph took a step forward. “Officer, that’s not—”

“Step back,” Boyd snapped, not taking his eyes off Camille. “Or you’ll be arrested for obstruction as well.”

Ralph stopped, jaw clenched.

At least three patrons had their phones out now, held low but angled just enough.

Camille set the pen down very carefully.

“I want this to be very clear on your body camera,” she said. “You are arresting me, Dr. Camille Hart, head librarian of this branch, for asking teenagers to be quiet in a library, and for declining to leave my workstation when you requested it without detaining me or stating any suspected crime.”

“Turn around,” Boyd repeated.

She did.

She felt the cold metal circle her wrists, the ratcheting clicks echoing in the suddenly too loud space. For a moment, nausea washed over her. Not from the cuffs themselves—she’d seen them before in other contexts, knew intellectually how they worked—but from the weight of what they represented when attached to her.

Librarian. Professor. Manager.

Criminal.

“Ralph,” she said, as Boyd guided her away from the desk, “call Director Thomas. Call the union. Make sure someone covers the STEM workshop at four.”

“I’ve got it,” Ralph said hoarsely.

And then she was walking past rows of books and stunned faces, toward the front doors, handcuffed in front of the kids whose overdue fines she’d quietly forgiven and the seniors whose printers she’d patiently unjammed and the children whose first storytimes she’d led.

Outside, the autumn air was bright and cold. The squad car idled at the curb.

Boyd opened the back door, guided her inside, and read her rights from memory.

The ride to the station took thirteen minutes.

Camille said nothing.

She didn’t need to.

The camera saw everything.

5. The Lawyer and the Pattern

By 5:30 p.m., Attorney Nadine Cole had watched the body camera footage twice.

She sat in a cramped interview room at the Easton City Police Department, tablet propped in front of her, wireless earbuds in, expression tightening slightly every time Officer Boyd raised his voice.

Nadine was forty, with sharp cheekbones and a sharper legal mind. She’d spent her career suing employers and government agencies for civil rights violations. Four years earlier, the city library workers’ union had put her firm on retainer “just in case.”

No one had expected “just in case” to look like this.

When the call came from Director Thomas—“They arrested Camille while she was on the desk”—Nadine hadn’t believed it.

Then she saw it with her own eyes.

Camille, calm, composed, asking “Am I detained?” in a level tone. Boyd avoiding the question. Camille offering witnesses and security footage. Boyd working himself up, then abruptly announcing the arrest.

It was textbook bad policing.

After the second viewing, Nadine took her earbuds out, pushed her chair back, and cracked her knuckles.

“This is going to cost them,” she said.

An hour later, the Commonwealth Attorney refused to file charges. “No crime here,” she said bluntly after watching the footage. “Release her.”

By 7 p.m., Camille was walking out of the station, wrists still marked from the cuffs but head high, flanked by Director Thomas and Nadine.

“I’m so sorry,” Thomas said. “We’ll issue a statement. We’ll—”

Camille held up a hand. “Don’t,” she said. “Not yet. Let’s do this right.”

She turned to Nadine. “What now?”

“Now,” Nadine said, “I start digging.”

She requested Boyd’s personnel file, dispatch logs, arrest reports from the last three years, body camera archives for every complaint-based call he’d taken.

The city dragged its feet. She filed formal discovery motions anyway. Two months later, a drive with over 400 hours of footage arrived at her office, along with thousands of pages of reports and records.

Nadine hired a data analyst.

Patterns emerged.

In an eighteen-month period:

Boyd had responded to 53 “employee being aggressive” calls.

39 involved Black employees or business owners.

In 28 of those 39, Boyd had detained, handcuffed, or arrested the employee.

In all 28 cases, witness statements and/or security footage contradicted the caller’s claim of “aggression” or “threatening behavior.”

The employees were store managers, restaurant supervisors, gym staff, a school secretary, a bus driver.

And now, a head librarian.

In almost every case, the employee had simply enforced a rule: no returns without a receipt, no service without ID, no entry to the pool after hours, no food in the computer lab.

In almost every case, the caller was white.

“Jesus,” Nadine muttered when she saw the chart the analyst compiled, red and blue bars starkly uneven.

“Is this one guy,” she asked, “or a culture?”

The analyst shrugged. “You only asked for his numbers.”

“Right,” she said. “For now.”

She also pulled the tapes for a subset of the calls—twelve in all. She watched them one after another late into the night.

Same pattern each time: Boyd arriving, speaking courteously to the white caller, then turning clipped, impatient, or adversarial with the Black employee when they explained their side, especially if they invoked policy or rights.

He’d threatened obstruction, disorderly conduct, “creating a disturbance.”

He’d used the threat of his authority to move them, silence them, punish them for not being deferential enough.

He treated complaints as gospel. He treated Black professionalism as defiance.

It was ugly. But it was solid gold in court.

Nadine drafted a complaint: Hart v. City of Easton, et al.

Defendants: Officer Ethan Boyd (individually and in his official capacity), Sergeant David Shaw (his supervisor), the Easton Police Department, and the City of Easton.

She alleged:

False arrest and unlawful seizure in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Equal protection violations under the Fourteenth Amendment.

State-law claims of false imprisonment and emotional distress.

Systemic failure to train and supervise, resulting in a pattern of racially discriminatory enforcement.

She attached exhibits: body cam transcripts, statistics, declarations from other employees Boyd had detained, a declaration from Director Thomas about Camille’s spotless 26-year record.

The complaint was 60 pages.

The exhibits were over 300.

When the City Attorney’s Office received it, one senior lawyer read through the first quarter, then pushed it away and rubbed his temples.

“We’re not taking this to trial,” he said.

“Settling?” a junior asked.

“Absolutely. And we’re rehabbing our complaint response policies whether we like it or not.”

6. The Lawsuit and the Settlement

Camille didn’t attend the initial mediation sessions. Nadine went with Director Thomas and a representative from the union.

The city’s lawyers came in looking tired, guarded, already on the back foot.

“Let’s be realistic,” one of them said. “There’s no appetite from the council to drag this through the press for two years.”

“Good,” Nadine said. “Because there’s no appetite from my side to accept ‘We’re sorry’ and a token check.”

They negotiated for eight months.

Money was rarely the hard part. The city’s insurance pool had set aside reserves for civil rights litigation. What Nadine wanted more than a dollar amount were changes:

Mandatory pattern analysis for officers with high complaint-based detentions involving employees.

New dispatch protocols, flagging repeat callers who reported multiple Black employees as “threatening.”

Body camera review by a supervisor before any obstruction or disorderly conduct charge filed against an employee in a complaint-only call.

Training on recognizing “weaponized complaints” and on how racial bias manifests when the caller is white and the employee is Black.

Public reporting every quarter of complaint-based arrests broken down by race and resolved outcomes.

The city balked.

“Do you want to pay Camille a lot more when we win at trial and get injunctive relief from a federal judge?” Nadine asked one afternoon, folding her hands.

They consulted with outside counsel.

In the end, the settlement, signed fourteen months after Camille’s arrest, contained:

$320,000 in damages to Dr. Hart.

Formal written apologies from the Mayor and the Chief of Police.

Implementation of the policies Nadine had demanded, with some modifications on timelines.

Agreement to use Camille’s arrest footage as a training case in the academy and in in‑service bias training.

The press release was careful, full of phrases like “learning opportunity” and “commitment to equity.”

Local media were less gentle.

“HEAD LIBRARIAN WRONGFULLY ARRESTED – CITY PAYS $320K, PROMISES REFORMS,” ran one headline.

Clips from the body cam footage—Camille calmly asking, “Am I being detained?”; Boyd declaring “You’re under arrest for obstruction” when she refused to step outside—ran on the evening news and bounced around social media.

The comments were predictable.

Some cheered Camille. Some vilified Boyd. A few insisted, “If she’d just done what he said, none of this would have happened,” missing the point entirely.

Camille didn’t read most of it.

She did watch the footage once, alone, in her living room. Watching herself in the grainy, slightly warped body cam perspective—her own face composed, eyes sharp, voice steady—felt like watching a stranger and a friend at once.

“Good,” she said quietly to the screen when her on-camera self said, “Then I am not leaving my post unless I’m detained.”

Nadine texted her a screenshot of the settlement’s last page with the judge’s signature.

You did that, she wrote.

Camille texted back:

WE did that.

7. Officer Boyd’s Fall

Officer Boyd was placed on administrative leave within a week of Camille’s arrest, pending the internal investigation.

By the time the settlement was approved, that investigation was over.

“We’ve concluded you engaged in a pattern of discriminatory enforcement and conducted an unlawful arrest lacking probable cause,” the letter from the chief read. “Your employment is terminated.”

His union filed a grievance.

At arbitration, his lawyer argued that Boyd had simply been “following his training” and that the city was using him as a scapegoat for systemic failures.

The arbitrator watched the body cam footage. He read the statistician’s report. He listened to testimony from a Black store manager Boyd had handcuffed after she refused a customer’s attempt to return worn clothing without a receipt. He listened to a Black assistant principal describe Boyd threatening her with arrest when she refused to let an angry parent skip security protocols.

“This is not a single lapse in judgment,” the arbitrator wrote. “This is a consistent misapplication of authority in situations where Black employees enforce legitimate rules and white complainants object.”

He upheld the termination.

Boyd applied to smaller agencies in neighboring counties. Each background check turned up the termination details. No one hired him.

He did one bitter interview with a talk-radio host, railing against “witch hunts” and “impossible expectations” and insisting he’d just been “trying to keep the peace.”

He never said Camille’s name.

Camille never said his again after the arbitration.

“He’s part of the story,” she told Nadine. “He’s not the whole story.”

8. Life After

The morning after the settlement was announced, Camille walked into the Jefferson Avenue Branch at 8:45 a.m., fifteen minutes before opening.

Ralph held the door for her.

“Morning, Dr. Hart,” he said.

“Morning, Ralph,” she replied.

The staff gathered in the break room: six librarians, four assistants, three part-time pages, and a clerk from circulation who’d arrived early.

Camille set a box of donuts on the table.

“We’re not celebrating what happened to me,” she said when someone started to clap. “We’re recognizing that it led to changes that make you safer when you do your jobs. That matters.”

One of the younger librarians, Marta, swallowed hard.

“I think about that girl in programming two years ago,” she said. “The mother who called the cops because she wouldn’t let her kid climb on the circulation desk. That could’ve been… this.”

“It won’t be,” Camille said. “Not anymore. Not in the same way. That’s why we did this.”

She didn’t say: Because I couldn’t stand the idea of any of you being cuffed in front of your patrons for doing what we pay you to do.

Later that day, a local TV crew came by to film B‑roll for a segment. They wanted a shot of Camille at the desk.

She agreed on one condition: that they also interview other staff and patrons, not just center her.

“I don’t want this story to be ‘hero librarian saves the day,’” she told the reporter. “This is about how easily authority can be abused when people trust one side of a story more than the other based on race and role.”

Her five-minute interview aired that night. In it, she explained in calm, measured language how “weaponized complaints” worked: how people who didn’t like being told “no” by a Black professional could outsource their anger to police, and how eager officers could act as enforcers without doing the work of verifying facts.

She ended with:

“I’ve worked in libraries for twenty-six years. We teach people how to find information, not how to jump to conclusions. I simply expect the same from our institutions.”

The clip traveled far beyond Easton.

A week later, Camille received an email from a librarian in Seattle. Then one from a school counselor in Texas. Then one from a Black nurse in Ohio who’d been reported to security three times by white patients when she enforced COVID rules.

“Your story made me feel less crazy,” the nurse wrote. “It’s not just me. It’s a thing. Thank you for naming it.”

Camille forwarded that one to Nadine with a note: This is why.

9. The Quietest People

Camille kept working.

She still shelved books when they backed up. She still helped patrons figure out why the printer refused to see their flash drives. She still ran her Saturday morning “History and Memory” book club.

Some days, when a patron raised their voice over a late fee or computer time, she felt a flash of something sharp under her breastbone. A memory of cold metal, of walking past the children’s area in cuffs.

Then she breathed, counted to four, and responded the way she always had: clear, firm, polite.

She donated $100,000 of her settlement to a local civil rights legal fund. She set aside $50,000 to start a scholarship for Black students pursuing degrees in library science.

With part of the rest, she fixed the leaky roof on her rowhouse and finally bought the piano she’d always wanted.

One evening, as she practiced halting, rusty chords in her living room, her phone buzzed.

A text from Nadine: Guess what’s in the new academy curriculum.

Attached: a photo of a slide projected on a classroom wall. On it, a still from Boyd’s body cam footage.

Caption: Case Study: Complaint-Based Responses, Bias, and Discretionary Arrests.

Under it, bullet points:

What did the officer do wrong?

How could this have been handled differently?

How do we recognize “weaponized complaints”?

Camille stared at the image for a long time.

She thought of the phrase in the narration at the start of Nadine’s legal brief, the one the lawyer had used when they’d first met:

“Sometimes the quietest people fight back the loudest.”

She hadn’t felt loud. She’d felt tired. But maybe she understood what Nadine meant now.

It wasn’t volume.

It was impact.

10. What It Meant

Six months after the settlement, Easton’s new policies started to show up in numbers.

The Public Safety Oversight Board’s first quarterly report noted:

Complaint-based arrests of employees had dropped by 46% compared to the same period a year earlier.

In the remaining arrests, supervisors reviewing body cam footage had reversed charges before arraignment in two cases, citing “insufficient cause.”

Eight repeat callers flagged by dispatch had been referred to the city’s conflict resolution office instead of automatically generating police response.

At the Jefferson Avenue Branch, nothing dramatic changed.

Which, Camille thought, was exactly how it should be.

Kids still sprawled on beanbag chairs reading graphic novels. Seniors still slept upright in armchairs. Writers still tapped away on laptops. Teens still talked too loudly sometimes and had to be shushed.

Life went on.

One afternoon, as Camille was re-shelving a cart of returns, she heard a familiar voice behind her.

“Dr. Hart?”

She turned.

It was Malik, now fourteen, at least six inches taller and a little shy about it. He held a school-issued Chromebook under his arm.

“Hi, Malik,” she said. “You’re getting tall.”

He grinned, self-conscious. “Yeah. My mom says I eat our grocery budget.”

“What can I do for you?” she asked.

He hesitated, then said, “We watched a video in our civics class. At Edison. It was you.”

“Oh?” she said carefully.

“Yeah.” He shifted from foot to foot. “Our teacher showed the part where you were like, ‘Am I being detained?’ and ‘What crime do you suspect me of?’ And she paused it and was like, ‘That’s knowing your rights.’”

Camille smiled despite herself. “Civics teachers are my favorite people.”

“She said we shouldn’t be disrespectful,” Malik added quickly. “Just… know what questions we can ask. I…I didn’t know you could do that. Ask, I mean.”

“You can,” Camille said. “You always can. Politely. Calmly. Even when you’re scared.”

He nodded slowly. “I was really scared that day,” he said quietly. “When they took you. I thought… if they can take you for no reason, what about me?”

“I know,” she said.

He looked up at her. “I’m less scared now,” he said. “Not like… not scared. But less.”

Camille swallowed past a lump in her throat.

“I’m glad,” she said.

He shrugged, suddenly bashful. “Anyway. I gotta go. My essay’s due tomorrow. I just wanted to say…thanks.”

“Anytime, Malik,” she said. “And good luck with that essay.”

He walked away.

She watched him weave between shelves, tall and thin and still a little boy around the shoulders, and thought, This is the real settlement.

Not the check.

Not the headlines.

A Black teenager feeling “less scared” because he’d seen an adult stand her ground and force a powerful system to admit it was wrong.

Camille returned the last book to the shelf. It slid into place with a soft, satisfying thump.

On her break, she stepped into her office, closed the door, and allowed herself, just for a moment, to sit back, close her eyes, and breathe.

Quietly.

Like in a library.

Where even the smallest sound can carry, if you listen hard enough.

End