The Night an Orphan Baby Bigfoot Snuck Into My Cabin – And Changed My Life Forever

I never thought I would put this down on paper. For three years I kept it to myself, convincing my rational mind that it had been stress, grief, isolation – anything but what it really was.

But last winter, standing in the snow with a fully grown Sasquatch cradling its own baby and placing a carved stone in my hand, I realized this story no longer belonged only to me.

This is the story of the night an orphaned baby Bigfoot stumbled into my mountain cabin in the middle of the worst blizzard in Montana’s recent history – and how that tiny, shivering creature tore open everything I thought I knew about the world.

Life at the Edge of the Wild

I live alone in a small cabin about fifteen miles outside of Whitefish, Montana, tucked into the dark, endless pines of Flathead National Forest. It’s a modest place: two small bedrooms, a kitchen, a living room with a wood‑burning stove, and a wraparound porch that looks out over an ocean of trees.

My nearest neighbor is seven miles down a dirt road that becomes useless as soon as winter really sinks its teeth into the land. I’m a remote software developer, so as long as I have a satellite internet link, I can work from just about anywhere. And after what happened to my wife, “anywhere” became “as far from town as I can reasonably survive.”

Three years ago, my wife disappeared in these same mountains.

We were weekend hikers, not experts but experienced enough to know better than to take stupid risks. We knew the trails, the weather patterns, the way the forest sounded when something was wrong. Or we thought we did.

One October afternoon she went out alone on a short hike – a loop she’d done dozens of times. A storm rolled in faster than forecast. She never came back.

Search teams combed the mountains for weeks. Helicopters, dogs, drones, volunteers. They found nothing. No pack, no jacket, no torn clothing, no body. It was like the forest had swallowed her whole and refused to give anything back.

After six months, the search was officially called off. After a year, people stopped asking how I was doing. Their lives moved forward. Mine didn’t.

I moved to the cabin to be closer to where she vanished. It was the only way I knew how to be near her – near the trails she loved, the ridgelines where she’d stop and close her eyes to feel the wind. Out here, the silence suited me. Or maybe I thought I deserved it.

My days fell into a simple rhythm. I coded from morning until late afternoon. In the evenings I read by the fire, listened to the wind scrape over the roof, and hiked familiar trails on weekends, tracing her steps through the wilderness she had adored.

The locals had their own stories about this forest. They talked about strange howls echoing at night, enormous footprints melting in the snow, glimpses of massive, upright figures moving between the trees. Bigfoot. Sasquatch.

I smiled politely when they spoke, but I didn’t believe. I chalked it up to folklore, campfire fuel, and the human tendency to invent monsters just beyond the tree line.

I was sure of one thing: whatever took my wife, it wasn’t a myth. It was just nature and bad luck.

I thought I had the forest figured out.

I was wrong.

The Once‑in‑a‑Generation Storm

The blizzard the meteorologists promised arrived in mid‑January.

They had been tracking it for days, calling it a “once‑in‑a‑generation” storm system sweeping in from the northwest. The maps on the television looked apocalyptic: swirling bands of deep blue and purple swallowing half the state.

I prepared the way any seasoned Montanan would. I stacked firewood under the porch roof until it resembled a small wall. I filled the pantry with canned goods, dried food, and bottled water. I checked the fuel levels for the generator twice and then checked them again. I knew from experience that when the power went down out here, it stayed down.

By Thursday evening, the sky had turned the color of old steel. The wind picked up, threading through the trees with a sound like a distant, wounded animal. Snow started falling in thick, heavy flakes that stuck to every surface they touched.

By Friday morning, three feet of snow lay on the ground. Visibility beyond the porch was down to ten feet at best; an endless white curtain erased the world beyond my front steps. The trees bent under the weight, creaking and groaning. Every so often I’d hear the sharp crack of a branch giving way, followed by the muffled thud of it disappearing into the snow.

The power lines went down around midnight. I switched to the generator and decided to conserve fuel as much as possible, using candles for light and the wood stove for heat. The cabin complained under the new weight on the roof, but it held.

The storm was terrifying and beautiful at the same time – nature flexing muscles humans like to pretend we’ve tamed.

By Saturday, things had gone from bad to surreal.

The snow was past four feet deep in open areas. Drifts had piled so high against the north wall of the cabin they reached above the windows. I was, for all practical purposes, sealed in. No vehicle was going anywhere. No one was coming up the road.

I wasn’t afraid. I had food, water, heat, and fuel. I’d planned for this.

What I hadn’t planned for was the sound.

The Cry on the Porch

It began as a faint, high‑pitched noise, barely audible over the constant roar of the wind.

At first, I dismissed it as the house settling or snow shifting off the roof. But then it came again – clearer this time. A sharp, thin cry that sliced through the howl of the storm.

It sounded like a baby.

I sat upright in my chair by the fire, every sense suddenly alert. The cry rose again, closer now. Desperate. Frightened.

Logic kicked in. No human infant could be out there and still be alive. Not in this cold, not in that wind. But my heart didn’t care about logic.

The sound seemed to be coming from the porch.

I grabbed my heaviest coat, pulled a wool hat over my ears, wrapped a scarf over my mouth and nose, and took my largest flashlight from the hook by the door.

When I cracked the door open, the storm hit me like a wall.

The wind tried to rip the door out of my hands. Snow blasted inside, stinging my face and swirling across the wooden floor. The cold was not just temperature; it was physical, a thing with weight and malice.

I forced the door wide enough to step out onto the porch and swung the flashlight beam across the boards.

At first, I saw nothing but snow – drifts piled against the railing, eddies swirling in the air, white chaos.

Then the beam caught something huddled in the far corner, pressed tight against the cabin wall where the wind had carved a shallow pocket of shelter.

A small shape. Curled. Shivering.

It was about the size of a medium dog, but the proportions were wrong. Its body was covered in dark, matted fur clumped with ice. It was curled into itself, arms wrapped around its knees.

The tiny creature was shaking violently, emitting those awful, thin cries that had pulled me to the door in the first place.

A thousand explanations flashed through my mind.

A wounded animal. A lost pet. Some kind of malformed bear cub?

Bear cubs aren’t out in January, I reminded myself. And bears don’t cry like that.

I moved closer, boots crunching in the blown snow. When my flashlight beam hit its face full on, my breath caught in my throat.

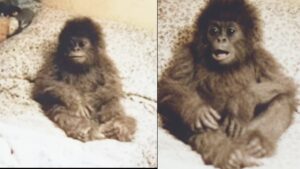

It was a face I had seen in sketches, in grainy photos, in “eyewitness reports” I’d always dismissed.

Almost human. Wide‑set dark eyes. A flat, broad nose. A short muzzle framed with fur, but clearly expressive. Intelligent.

A baby Bigfoot.

The little creature blinked up at me, eyes huge with terror and exhaustion. One small, fur‑covered hand lifted toward me, fingers trembling.

Whatever fear I should have felt – fear of the unknown, fear of something that shouldn’t exist – vanished beneath something else: the raw, undeniable need in that tiny face.

I didn’t think. I acted.

I scooped the baby up in my arms.

A Creature in the Firelight

The baby was shockingly light. Under all that fur, bone and skin. Severe malnourishment, I realized later.

The creature whimpered, but did not fight me. As I turned and stumbled back into the cabin, it clung to my coat with surprising strength for something so weak.

I kicked the door shut with my heel and lowered the wooden bar across it with my free hand.

The difference between outside and inside hit me like a scene change. Outside, howling white chaos. Inside, dim candlelight and the orange glow of the wood stove, the air thick with the smell of smoke and pine resin.

I knelt by the fire and gently set the baby down on the rug.

Up close, in the flickering light, there was no room left for denial.

The creature was not a bear. Not a monkey. Not any animal I had ever seen in the wild or in a book.

It was a juvenile Sasquatch.

Dark brown fur, almost black in places, covered most of its body. The fur was tangled and heavy with snow and ice, especially on its legs and back. Beneath the fur, patches of skin showed along thin arms and at the throat, grayish and chilled.

The face was eerily human in its expressiveness. Large, liquid brown eyes watched me warily. The nose was flat and wide. The mouth – when it opened to cry softly – revealed small, white teeth set in gums not unlike a human toddler’s.

Its hands and feet were like a child’s, but larger and broader, covered in fur up to the fingers and toes, which ended in short, blunt nails. The proportions were slightly off: arms a bit too long, feet broader, shoulders more developed.

But the emotions flickering across that little face were instantly recognizable.

Fear. Pain. Exhaustion. And beneath all of it, a fragile, desperate hope.

I moved slowly, murmuring nonsense in a calm tone, the way one might approach a frightened dog or a crying child. The baby flinched at first when I reached out, but did not pull away when my hand touched its arm.

The cold radiating off its body was shocking. Even through the thick fur, it felt like holding a bag of ice.

Hypothermia, I thought. And shock. Whatever had happened to it out there in the storm had nearly killed it.

Its breathing was shallow and rapid. Its small chest hitched with each sighing cry.

If I didn’t do something, this creature would die right here on my floor.

I didn’t know if there were other Bigfoot nearby. I didn’t know if taking it in would bring danger to my doorstep.

I only knew that something helpless had landed on my porch during the worst storm I’d ever seen, and I was the only one who could help.

I carried the baby closer to the wood stove and set it gently on a folded blanket I dragged from the back of the couch.

Then I went to work.

Saving a Life I Didn’t Understand

Years of backcountry hiking had taught me basic field first aid. None of that training mentioned “infant Bigfoot,” but some principles are universal.

Warm slowly. Don’t shock the system. Address injuries. Provide water and food, but not too much at once.

I grabbed every towel I owned and filled a basin with warm – not hot – water from the pot on the stove. Sitting cross‑legged beside the creature, I began carefully working the ice out of its fur, towel by towel, section by section.

The baby shivered violently at first, teeth chattering audibly, but as the minutes passed and the fur dried, the shaking eased. Every now and then it made small, questioning sounds, its ears – small, partially hidden under the fur – twitching when I spoke.

I talked constantly, though I have no idea what I said.

“You’re okay. You’re safe. We’re going to get you warm. I’ve got you. You’re okay.”

Whether it understood the words or just the tone, I don’t know. But it never tried to bite or scratch. It simply lay there, occasionally reaching out to grip my sleeve or my wrist with those tiny, chilled hands.

It had a gash on one leg, not deep but angry‑looking, the fur around it matted with dried blood. There were scratches on its arms and face. Something had happened out there – a fall, a fight, separation from its family – that left it alone in the teeth of a once‑in‑a‑generation blizzard.

When the fur was free of ice and mostly dry, I cleaned the wounds with warm water and a mild antiseptic. The baby flinched, but made no sound of protest.

Either it was too weak to resist, or it had already learned that showing pain didn’t help.

As the heat from the stove seeped into the room, the baby’s breathing deepened. The tremors faded to occasional shivers. Its eyes, which had been half‑closed with exhaustion, began to open wider, tracking my movements, the firelight, the shadows on the ceiling.

When I brought over a small bowl of warm chicken broth and held a spoon toward its mouth, it sniffed the air, then leaned forward and lapped at the liquid.

The sound it made – a sort of low rumbling, almost like a purr – was the first sign of contentment I had seen. It drank greedily, so quickly I had to stop it every few spoonfuls for fear it would make itself sick.

After half the bowl, its eyelids drooped. It curled into a tighter ball near the stove, head resting on its arms, and slipped into a restless sleep.

I sat there on the floor for a long time, watching this impossible creature breathe, the firelight painting its fur in shades of copper and gold.

The storm raged on outside. The roof groaned. The wind battered the walls.

Inside, something far stranger and more fragile was happening – a human and a Sasquatch sharing warmth and shelter in a tiny cabin no one would ever think to search.

A New Routine – And a New Language

I didn’t sleep much that night.

Every whimper from the small body by the fire had me out of bed and kneeling beside it, checking its breathing, adjusting blankets, offering water. The baby thrashed occasionally, letting out sharp cries that sounded eerily like nightmares.

I had never had children of my own. My wife and I had talked about it, but life and careers and then the accident had intervened. Yet everything in me responded to this tiny being with a protective instinct I hadn’t known I possessed.

By morning, the storm was still a white wall outside. But inside the cabin, the little Bigfoot – because that’s what it undeniably was – seemed stronger.

When I awoke fully, rubbing the sleep from my eyes, I found it sitting up near the stove, staring at me with open curiosity.

The moment I moved, it made a soft sound and crawled toward me. Not walking yet – whether from age or lingering weakness, I couldn’t tell – but moving with surprising coordination.

I made oatmeal with honey and mashed banana and offered a small portion. It sniffed the bowl, then dug in with both hands, shoveling food into its mouth with gusto.

I couldn’t help but smile. There was something indescribably endearing about the way its whole face lit up at the taste of something warm and sweet.

Over the next few days, as the blizzard slowly spent itself, we fell into a rhythm.

At night, the baby – I started calling it “Little One” – slept near the fire on a nest of blankets I arranged. During the day, it shadowed me.

If I went into the kitchen, Little One crawled after me, pulling itself up to peer over chair rungs and cupboard doors. If I sat down to work at my laptop, it settled at my feet, occasionally reaching up to touch the cables or the keys with gentle, curious fingers.

It never let me out of its sight.

The cabin, which had felt so cavernous and hollow after my wife’s disappearance, suddenly felt full. Alive.

I began to recognize patterns in Little One’s sounds.

A soft, rapid chirping when it was content. A louder, insistent chirp when it wanted my attention. A low whining note when it was uncomfortable or frightened. A rapid, excited chattering when I brought food or when something new caught its interest.

I realized I was learning a language – not of words, but of tones and context.

Little One was endlessly curious. Everything became an object of study. Spoons, books, pieces of firewood, my boots, the iron poker by the stove – it would pick each item up, turn it over, sniff it, tap it against the floor or another object to see what sound it made.

One afternoon, while I was reading in my favorite chair, Little One did something that made my heart skip.

It crawled over to a book I had left on the floor, picked it up carefully in both hands, opened it, and began slowly turning the pages.

Not tearing. Not chewing. Looking.

When I moved closer, it ran one small finger under the lines of text, then looked up at me and made a questioning sound, as if asking: What is this? What do these marks mean?

The intelligence in that simple gesture was staggering.

That evening I began reading aloud.

In the firelight, with the storm fading outside and the world reduced to the circle of warmth around us, I read to a baby Bigfoot. Sometimes novels, sometimes natural history, sometimes poetry. Little One would curl against my leg and listen, eyes fixed on my face, occasionally making soft, commentary‑like noises at moments of particular emphasis.

Did it understand the stories? I doubt it, at least in the way we do. But it understood tone, rhythm, emotion.

It fed on connection.

Learning Each Other

As the days turned into a week, the storm finally broke.

I woke one morning to a silence so complete it startled me awake. No wind. No pellets of ice striking the glass.

I rolled out of bed, padded to the window, and pulled aside the curtain.

The sky above the pines was impossibly blue. Sunlight glared off an unbroken expanse of white. Everything was buried. My truck was a rounded mound barely distinguishable from the surrounding drifts. The woodshed looked like a snow dune. The forest was transformed into a fairy tale, every branch outlined in glittering ice.

Little One toddled over and tugged at my pant leg, making a questioning chirp. I lifted the baby – heavier now, warm and solid – and held it up to the glass.

It pressed both hands against the cold windowpane and made an excited sound. Its eyes widened at the brightness, at the changed shape of the world.

I wondered what it remembered of the forest. Of its family. Of whatever disaster had separated it from them in the first place.

I had a new problem now.

The roads would eventually be plowed. Life would resume. I could get to town again, check in, buy supplies.

But what was I going to do about the small, impossible being sharing my cabin?

I couldn’t call animal control. “Hi, I’ve got a baby Sasquatch in my living room” was not a sentence that ended in anything but disbelief, a psych evaluation, or men in unmarked trucks.

If anyone believed me – if I somehow produced proof – the best‑case scenario for Little One would be a lab, a cage, and a lifetime of being probed and measured. The worst‑case scenario involved guns and mounted heads.

I could keep it, I thought. Raise it. Hide it.

Then I imagined what Little One would look like one year from now. Five years. Ten. The power in those small hands, the width of those shoulders, hinted at the adult it would become.

Could I help it grow up healthy trapped in a cabin, cut off from its own kind? Could I live with myself if I tried?

The answer was obvious, and it hurt more than I expected.

But nature made the next move before I could.

The Calls from the Trees

We spent two full days digging the cabin out from six feet of dense, compacted snow. I shoveled paths to the truck and the woodshed, cleared the roof edges, knocked ice from the eaves.

Little One watched from various windows, pressing its face to the glass and making encouraging sounds whenever I glanced up.

Inside, our routine continued. Little One gained strength rapidly. By day three after the storm, it was standing on two legs and taking wobbly steps. By day five, it was toddling around the cabin with the clumsy confidence of a human toddler, exploring every hidden corner.

It seemed omnivorous, eating just about everything I offered: vegetables, fruit, eggs, meat, bread. It developed a special love for anything sweet – honey, jam, dried fruit – its eyes lighting up with pure joy whenever those treats appeared.

It was clear now that Little One wasn’t just surviving; it was thriving.

And then, on the third day after the sky cleared, I heard the sound.

I was carrying in an armful of firewood when a deep, resonant call rolled through the forest. Not a wolf. Not an elk. Not any animal I knew.

The sound vibrated in my chest.

Little One froze. Its ears perked forward, eyes wide. It scrambled to the nearest window, pressing its face against the glass, answering with a high‑pitched chirp I hadn’t heard before – frantic, insistent.

Another call came, closer this time.

If the first had been a question, this one was an answer: I am here. Where are you?

Little One began to cry. Not with fear, but with overwhelming excitement. It ran to the door, pawing at it, looking back at me, making desperate, pleading sounds.

My heart started hammering.

I grabbed my binoculars and scanned the tree line beyond the clearing, sweeping slowly from left to right. For a moment I saw nothing but shadows and snow.

Then movement.

Two massive figures stepped out from between the trees.

They moved with fluid ease through snow that reached my thigh. They were huge – at least seven or eight feet tall – covered head to toe in thick fur the same dark brown as Little One’s.

Adult Bigfoot.

They stopped at the edge of the clearing, shoulders squared, heads high, scanning my cabin with unnervingly intelligent eyes.

Beside me, Little One was a blur of motion, jumping up and down, crying and chirping, scratching at the door.

Family, I thought. It has to be family.

Relief and dread crashed into each other in my chest. Relief that Little One would not be alone anymore. Dread at the thought of letting it go.

The larger of the two – broader shoulders, darker fur, scarred arms – stood slightly in front of the other. Male, I guessed. The protector. His fur was so dark it was almost black in places, streaked with silver around the muzzle. Old wounds crisscrossed his chest and forearms, scars of battles with predators or rivals.

The smaller one – still enormous by human standards – stood half a step behind him. Her features were softer, her fur a rich chestnut. Her eyes never left the cabin windows.

She raised her head and let out a long, warbling call, laden with emotion.

It was the same pattern Little One had been making – but older, deeper, more powerful.

A mother’s voice calling her lost child.

Little One nearly flew at the door, crying back with such force that my eyes stung.

That was all the answer I needed.

Reunion in the Snow

Fear of what those towering creatures could do to me if they chose to never left my mind. But in that moment, it felt smaller than everything else.

I put on my coat with shaking hands.

Little One bounced at my feet, nearly tripping me in its eagerness to be outside. I picked it up one last time. It wrapped its arms around my neck, pressing its face into my collar, making soft, excited sounds that vibrated against my skin.

I opened the door.

Cold air cut into the cabin, swirling around us. Snow squeaked under my boots as I stepped onto the porch.

The two adults moved closer, stopping about twenty feet away. The male positioned himself slightly in front of the female, his body language unmistakably protective.

Up close, their presence was overwhelming. They were not just big; they were there in a way most humans rarely are. Every movement was measured, purposeful. Every line of their bodies radiated strength.

I held Little One up so they could see the baby clearly.

The female made a sound that broke something in me. Half sob, half laugh. Pure relief.

She took a step forward and would have taken another if the male hadn’t lifted one hand to her chest, stopping her.

His eyes were on me.

Not on my hands, not on my feet, not on the gun I wasn’t carrying.

On my face.

I don’t know how long we stood there, staring at each other. The wind whispered through the trees. Little One wriggled in my arms.

I saw caution there. Wariness. But I also saw something else: comprehension.

He knew. Somehow, at some level beyond words, he understood that this strange, fragile creature in front of him – me – had kept his baby alive through the storm.

He made a low, rumbling sound. Not a threat. A statement.

I took a slow step forward.

Then another.

Snow crunched. The distance between us shrank.

At about ten feet away, I knelt and set Little One down on the snow.

For an instant, to my surprise, the baby didn’t run to them. Instead, it turned and threw its arms around my leg, hugging as tight as it could.

I put a hand on its small, furred head.

“Go on,” I whispered, though it didn’t need the words.

Little One looked up at me one last time, reached up to touch my face – the same gesture it had used so many times by the fire – and then turned and ran.

I will carry the sight of that run with me to my last breath.

The female broke into a lumbering rush to meet the baby halfway, scooping it up in arms that could have snapped a tree in half. She held Little One against her chest, rocking, vocalizing a stream of sounds that were clearly the Sasquatch equivalent of sobbing laughter.

The male stepped forward, wrapping his arms around both of them. The three of them stood there, locked together, a tight knot of fur and muscle and relief.

A family, whole again.

I watched from the porch, tears freezing on my cheeks.

The mother checked Little One all over, running massive fingers over its limbs and face, inspecting the wound on its leg, sniffing at the blankets of my scent still clinging to its fur. Little One chattered back, pointing at the cabin, at me.

The female’s eyes met mine over her child’s shoulder.

In that gaze, there was no hatred. No mindless ferocity.

There was gratitude.

After a long moment, I began backing toward the cabin, not wanting to intrude on their reunion.

But the male had one more move to make.

He gently took Little One from the female’s arms again, murmured a low sound I couldn’t interpret, and walked toward me.

My heart hammered. Every instinct screamed at me to get inside, bar the door, grab a gun I didn’t own.

I forced myself to stay.

He stopped a few feet away. Little One reached for me, giving my leg one last hug.

Then the male did something I never expected.

He extended one enormous hand and placed it, very gently, on my shoulder.

The weight was firm, but not painful. Deliberate, but not aggressive.

It was a gesture every human recognizes, regardless of culture.

Thank you.

He held my gaze for one long, suspended moment. I saw intelligence there. Emotion. The same messy, complicated mix of fear and love and gratitude I’d seen in human parents in hospital corridors and school parking lots.

Then he turned, lifted Little One effortlessly into his arms, and walked back toward the tree line.

Little One twisted in his grip to look back at me. The baby raised one small hand and waved.

I waved back, my throat too tight for words.

The family of three moved across the snow and disappeared into the forest.

I stood on the porch until the wind erased their tracks.

Living With a Secret

The cabin felt cavernous that night.

The nest of blankets by the fire sat empty. The small bowl I had used for Little One’s meals sat washed and drying on the counter. Every creak of the settling wood sounded like tiny footsteps that never came.

Snowplows eventually reached the road. My internet sputtered back to life. Emails and deadlines flooded in as if nothing in the world had changed.

But everything had.

I went back to my job. I joined video calls. I fixed bugs in code. Colleagues commented that I seemed distracted.

“Cabin fever?” one of them joked. “You need to get into town more, man. You’re starting to look like a mountain hermit.”

I laughed it off.

How do you tell someone that their reality is too small? How do you say, “A week ago, I held a baby Sasquatch in my arms and handed it back to its parents in a snowfield”?

You don’t.

Not if you care about your freedom. Not if you care about the creatures in question.

I dove into research instead.

Late at night, lit only by the glow of my monitor and the embers of the stove, I read everything I could find about Bigfoot: first‑hand accounts from hunters and hikers, Native stories that went back centuries, grainy photos, shaky videos, skeptical debunkings.

Most of it, I dismissed as hoax or misidentification. But some accounts – especially those from the local Salish and Kootenai people – resonated with what I had seen. Stories of tall, furred beings in the deep woods, family groups, creatures who avoided humans but were not inherently hostile. A people, not a monster.

I recognized their descriptions. I had seen their eyes.

I decided two things.

First: I would never try to prove what had happened. Not with photos, not with video, not with “evidence.” I would not invite the world into their forest. They deserved their anonymity more than we deserved proof.

Second: I would watch. And I would wait.

I began leaving small offerings at the edge of the clearing – apples, dried fruit, nuts, jars of honey – placed on a flat stone near the tree line. Sometimes they disappeared overnight. Sometimes they sat untouched for days. I never saw who – or what – took them.

The absence of Little One was an ache that didn’t fully fade. I found myself still pouring two mugs of coffee in the morning by mistake, or turning to comment on something only to find an empty space where a small, furred shadow had once been.

Then, two weeks after the reunion, the forest gave something back.

Gifts From the Trees

I was bringing in an armload of firewood one evening when a familiar sound cut through the quiet.

A high, trilling chirp.

My heart nearly stopped. I dropped the logs and spun toward the tree line.

There, standing at the edge of the clearing in the fading light, was Little One.

Not so little anymore. In just two weeks, the baby had grown, its fur filled in, its posture stronger. Beside it stood the female – its mother – watching me with that same calm, assessing gaze.

Little One waved both arms in the air, making excited, bubbling sounds.

I walked slowly toward them, hands open at my sides. The female watched every step, her body slightly tensed but not retreating.

When I was close enough, Little One bounded forward and wrapped its arms around my legs in a familiar, crushing hug. I laughed aloud, feeling tears sting my eyes.

I had assumed I would never see it again. That the forest would simply swallow that chapter of my life and move on.

But here it was.

After a moment, Little One stepped back, reached into the thick fur on its chest, and pulled something out.

A smooth, round stone. River‑worn. It held the stone out to me with both hands, making soft, insistent sounds.

A gift.

My throat tightened as I took it. The stone was warm from being nestled against its body. I closed my fingers around it, feeling the weight.

Behind Little One, the female made a gentle sound. Little One looked up at her, then back at me. The baby hugged me one more time, patted my hand, and returned to its mother’s side.

They stayed only a short while. Long enough for me to see that Little One was healthy, thriving. Long enough to know that I had not imagined this entire thing.

As they turned to go, the female looked back at me and – I swear – nodded. Just once.

Then they were gone.

Over the following months, the visits continued.

Sometimes Little One appeared alone, bounding out of the trees to sit on my porch, play in the snow, or simply watch me repair a fence or stack wood. Sometimes the mother stood at the tree line while Little One ventured closer. Once, the entire family came – father, mother, and juvenile – standing at a respectful distance while Little One made excited sounds and encouraged them to take the food I’d laid out.

The gifts went both ways.

I left apples, oranges, dried meat, bread I’d baked that morning. They disappeared quickly on some nights, not at all on others.

In return, I found things on my porch: a perfect golden eagle feather, laid carefully in the center of the boards. A bouquet of wildflowers – columbine and Indian paintbrush – bound together clumsily with grass stems. And one morning, a spiral of river stones arranged on the porch with clear deliberation.

It was not random. It was art. Or language. Or both.

I took photos of the spiral before moving it to a sheltered corner of my small garden.

The forest around me changed, too – or maybe I just learned to see more.

I began to notice tree trunks with parallel scratches at different heights, like height measurements. I found footprints near the creek – huge, human‑like prints in the soft mud that started and ended at the waterline. Once I discovered a small lean‑to structure woven of branches, just large enough for a young Sasquatch to crawl into. Practice shelter, I thought. Training.

The more I watched, the more it became impossible to think of them as animals.

They were a people.

A Bridge Between Worlds

Seasons turned. Snow melted. Wildflowers painted the meadows. Summer thunderheads rolled over the peaks.

The visits became a dance. We maintained distance but built trust.

In late summer, Little One arrived at the clearing with two smaller figures darting at its heels – tiny, wide‑eyed baby Bigfoot, probably siblings or cousins born that spring.

Little One moved with a grace and confidence that made my chest ache with pride. The child I’d held in my arms was now nearly as tall as my chest, muscles filling out, face sharpening from round infant softness into the features of an adolescent.

The two babies peeked from behind its legs, eyes huge, bodies tense with curiosity and fear.

Little One chirped at them in a soothing tone, then gestured toward me.

I sat down in the grass, making myself as small and unthreatening as possible.

After a moment of hesitation, one of the little ones toddled forward and reached out a tiny hand to poke my boot. I didn’t move. The second followed, sniffing my hand when I offered it, then patting my fingers with a delighted chirp.

I realized what was happening.

Little One was teaching them. Teaching that this particular human, in this particular clearing, was safe.

Passing on the knowledge we had built together.

The thought nearly undid me.

We spent perhaps twenty minutes together. The babies explored my hair, my sleeves, the fabric of my shirt, giggling in their strange, chattering way. Little One remained close, eyes flicking between them and the tree line, the protective instinct I’d seen in its father now blossoming in it.

When a distant call echoed from the forest – the mother’s voice, summoning – Little One gently herded the babies back toward the trees.

Before leaving, it turned back and placed one hand over its chest, then extended the hand toward me.

I mirrored the gesture.

A symbol, unspoken but understood. Heart. Friend. Family.

That fall, I made changes.

I reinforced a three‑sided shelter near the trees and kept it stocked with non‑perishable food, blankets, and basic medical supplies. If another storm came, if another young one was caught out… there would be options.

I never told anyone what the shelter was really for. When asked, I shrugged and said it was a hunting blind. Out here, no one questions a man for building one of those.

I became more careful with my noise, my lights, my trash. This was their home more than mine, I realized. I was the guest.

Full Circle

Years passed faster than I expected.

Little One grew.

By the time another deep winter settled over the mountains, the young Sasquatch was nearly my height, then taller. It visited less frequently. When it did, I saw more of the forest in its posture, in the way it moved. It was becoming what it was always meant to be: a creature of the wild, perfectly at home among the shadows and snow.

I didn’t begrudge that. That’s what I had wanted for it all along.

And yet each visit felt more precious.

One gentle snowfall night, I heard a soft, unmistakable chirp on the porch. I opened the door to find Little One standing there, fully grown now – nearly seven feet of muscle and fur, snow dusting its shoulders.

It held out another stone.

This one was different. Still smooth and river‑worn, but carved now with deliberate markings: lines and shapes that might have been symbols, or a map, or something else entirely beyond my understanding.

I took it with reverence.

Little One reached out and touched my face gently with the back of its fingers, the way it had as a frightened baby in my cabin years before.

Then it turned and walked back into the falling snow, leaving footprints that the storm quickly blurred.

I took that as what it was: a closing of a chapter. A marker of maturity. A thank‑you, carved in stone.

I placed that stone on my desk beside the first smooth one and the eagle feather. A small, private shrine to a reality the wider world still scoffs at.

Life continued.

I worked. I hiked. I left offerings at the forest edge and occasionally found gifts in return. The forest became less a backdrop and more a community I shared space with.

Three years after the night of the blizzard, on a bright spring morning, I was finishing my coffee when I heard that sound again.

The chirping trill that had once pulled me out into a deadly storm.

I set the mug down and went to the door.

At the edge of the clearing stood Little One.

Fully adult now. Broader through the shoulders, posture settled into the effortless balance I’d seen in its parents. Beside it stood another adult – slightly smaller, with lighter fur. Its mate.

And cradled in Little One’s arms was the tiniest baby Sasquatch I had ever seen.

Dark fur still soft and tufted, eyes barely open, tiny fingers gripping at its parent’s chest.

My vision blurred. For a moment I couldn’t move.

They had come to introduce me to their child.

I walked slowly out into the clearing. The other adult watched me closely, wary but not aggressive.

When I was close enough, Little One shifted the baby, tilting it so I could see better. The infant blinked at me, unfocused, then nuzzled back into the fur.

Little One made soft sounds to its mate, then gently took one of the baby’s hands and guided it toward my outstretched finger.

The tiny fingers curled around mine with surprising strength.

We stood there in the sun for a long, quiet moment – two adult Bigfoot, one human, one newborn – sharing a connection that needed no words.

Finally, Little One reached into its fur again and brought out a third stone.

This one was the most elaborate yet, covered in carved patterns that flowed together in ways I couldn’t decipher but that were clearly meaningful to the one who had made them.

Little One placed the stone in my palm and closed my fingers around it.

I knew what it meant.

Goodbye. Thank you. Remember.

I placed my hand over my heart and extended it toward them. Little One mirrored the gesture, then touched the baby’s tiny hand to its own chest and then briefly toward me.

Teaching. Passing on the story.

Then, with one last look – full of gratitude, love, and a kind of quiet pride that needed no translation – Little One turned and walked back into the trees, its mate at its side, their child safe in their arms.

The forest swallowed them.

Keeper of the Bridge

People sometimes notice the stones on the shelf behind me during video calls.

“Nice rocks,” they say. “River stones?”

I nod and say yes.

It’s not a lie. Just not the whole truth.

I have learned something in these years.

Legends exist for a reason.

Stories of wild, furred giants in the woods, passed down through generations, aren’t just entertainment for tourists or cautionary tales for kids. They’re the echo of real encounters, dimly remembered and distorted by time, but tied to something solid and breathing.

Bigfoot are not monsters. They are not supernatural. They are not figments of stressed minds.

They are living, breathing beings – intelligent, emotional, social. They raise children. They grieve. They give gifts. They remember kindness.

And sometimes, when the world is howling and the snow is three feet deep on your porch, one of their smallest will stumble into your circle of light and need you.

That winter night, I thought I was saving a baby Bigfoot.

I have come to understand that Little One saved me, too.

Saved me from drowning in grief. Saved me from believing the world was small and empty and fully mapped. Saved me from the kind of numbness that looks a lot like being alive but isn’t.

I live now with the knowledge that just beyond the tree line, lives are unfolding that we know almost nothing about. And I live with the responsibility of being a bridge – however small – between our world and theirs.

I will likely never have proof that convinces anyone who needs proof. And I am glad of that.

Some secrets deserve to be kept. Some doors, once opened, must be guarded.

So I keep the shelter stocked. I keep the porch light on in bad weather. I listen, on still winter nights, for a faint chirping trill in the storm.

I don’t know if Little One will ever bring that baby to see me again. I don’t know if I will ever lay eyes on another Bigfoot.

But I will be here, at the edge of the wild, ready.

Because once you have held a baby Sasquatch in your arms and looked into the eyes of its parents, you can never go back to believing the forest is empty.

The wilderness is bigger than we think. And if you are very lucky, one night, in the middle of a blizzard, something extraordinary will find its way to your door and remind you what being alive really means.