The Man Who Raised the “Twins” in the Cascades: A Confession About Mercy, Betrayal, and the Footage He Never Released

By [Your Name]

Milbrook, Washington —

1) The Crying by the Creek

He remembers the exact week the forest changed its color.

Late September 2014, just after the first cold snap that darkens Douglas firs and makes every sound carry farther. He was 42, living alone in a cabin his grandfather left him, three miles from the nearest gravel road, hemmed in by old growth on three sides. No neighbors within shouting distance. After a divorce, isolation had felt like freedom.

That morning he was splitting wood behind the shed when he heard what he first took for a wounded animal—thin, high-pitched crying, frantic in a way that didn’t match any coyote or cougar call he knew.

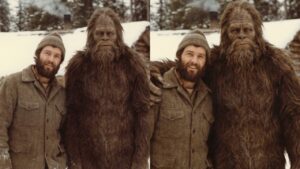

He followed the sound to a creek bed and found them near a rotted hemlock log: two infants curled together, barely alive, eyes only partly open, covered in matted black hair. No mother. No obvious den. No tracks he recognized, at least not then.

“I know what people think when they hear about raising wild things,” he would later write, “but I wasn’t thinking clearly. They were dying.”

He brought them inside.

That is the first decision in his story—the one he insists was mercy, not curiosity. The one he insists he made with shaking hands and a mind already too lonely for its own safety.

He didn’t call wildlife authorities. He didn’t call a university. He didn’t call a friend.

He did what people do when they find something helpless and they are alone enough to believe they can become its whole world.

He tried to keep them alive.

2) The First Week: Goat’s Milk and a Secret He Wouldn’t Name

He fed them goat’s milk from a bottle every four hours. He built a pen from chicken wire and 2x4s and lined it with blankets. He didn’t know what else to do. A person can be a software contractor and still be powerless in the face of two starving beings.

They grew fast. Doubling in size within a month.

By October, they were walking—clumsy, determined—gripping his fingers with hands that already felt too strong. In his telling, the strength wasn’t animal strength, not the mindless force of a bear cub. It was directed, as if the muscles were learning their own purpose sooner than they should.

He named them quietly in his head, though he claims he never said the names out loud. The male was larger and more curious. The female watched everything with dark, intelligent eyes, the kind of still attention that makes you feel examined.

In those early months he was still calling them temporary.

Temporary care. Temporary shelter. Temporary secrecy.

“I told myself it was temporary,” he wrote. “That I’d figure out what to do with them when they got bigger.”

But the cabin was isolated, and isolation turns short-term plans into habits. Habits become life.

Outside, he kept a small chicken coop—six hens for eggs—and two goats for milk. Self-sufficiency, he called it.

Then the twins arrived and self-sufficiency became something else: a closed ecosystem. A hidden household. A private universe where the rules belonged to him, until they didn’t.

3) The Cabin Routine: When “Animal” Stops Fitting

By November, they’d learned to open the cabin door if he forgot to latch it. He’d catch them sitting on the porch in morning fog, silent, watching the treeline as if they were listening to a frequency he couldn’t hear.

He kept them hidden.

He calls that mistake number one.

He knew how absurd it sounded: a middle-aged man raising something that wasn’t supposed to exist—something he wouldn’t yet name even to himself. So he stayed quiet. He paid cash. He lied.

He told himself he was protecting them from the world.

Looking back, he admits the other truth: he was protecting himself from the world’s judgment and from the consequences of admitting what he’d done.

They weren’t “just animals,” he says. They understood routines. When he sat down at his laptop for work, they’d settle near the wood stove without making a sound. When he cooked, they watched him measure and stir with an attention that felt uncomfortably human.

He began keeping a journal: dates, times, what they ate, how they reacted to sounds. By December, he’d spent over $1,000 on raw meat from a butcher two towns over. He told the butcher he was feeding sled dogs. The butcher never asked why he paid in cash.

Winter came hard. Snow piled three feet deep by January. The road became impassable except by snowmobile. He didn’t mind. The twins thrived in the cold. They rolled in drifts, making sounds he describes as somewhere between laughter and howling.

He watched from the window with coffee going cold in his hand and felt something that scared him more than their strength:

He felt proud.

4) The Visitors: The Lies That Became a Way of Life

He says the first year could have ended differently if not for the visits.

Only two engines came near the cabin that winter. Once, a lost hunter. Once, a county road crew checking on residents after a storm.

He lied through his teeth both times.

Said he was fine. Said he was alone. Said he didn’t need anything.

The twins learned to read him. If he was stressed about work, they stayed in the back room. If he was relaxed, they brought him offerings: bark, stones, objects found in the woods.

The female once brought him a dead mouse and placed it carefully at his feet, as if presenting tribute. He praised her because he didn’t know what else to do—and because praise, he was learning, shaped behavior.

This is the quiet horror of his story: how easily affection can become training.

5) The Sound Like Language

By March, the twins were “speaking” to each other—not words, but low vocalizations that carried meaning he couldn’t parse.

They sat facing each other for long stretches, making sounds back and forth, a rhythm that felt less like animal call-and-response and more like conversation. He recorded it on his phone.

“That’s when I first realized,” he wrote, “that whatever they were, they weren’t just some unknown primate species. They were thinking, planning, remembering.”

His journal entries grew longer. He documented height, weight, patterns, social behaviors. Part of him knew he was sitting on something extraordinary, something that could rewrite textbooks and destroy reputations.

And still he stayed quiet.

Because by then, he admits, he was no longer simply “keeping them safe.”

He needed them.

“It felt like family,” he wrote. “I know how that sounds.”

It sounds like love. It also sounds like possession. In the wild, those two often live in the same body.

6) Tom Bridger and the Beginning of Suspicion

The first pressure from the outside world came in April, in the form of a man named Tom Bridger—someone he rarely saw, passing by on his way back from setting trap lines.

Tom leaned against his truck and squinted at the cabin.

“Heard some strange sounds coming from your direction last month,” Tom said. “Thought maybe you got dogs.”

He shrugged, tried to keep his voice casual. “Probably coyotes.”

Tom nodded slowly, not convinced.

“Also found some weird tracks down by the creek,” Tom added. “Big, not bear, not elk. Almost looked like…”

He trailed off.

“Like what?” the narrator asked, already feeling his stomach tighten.

Tom hesitated. “Nothing. Just odd as all.”

Tom drove away, but glanced back in the rearview mirror.

That conversation stayed like grit under the skin. The narrator became more careful: no more letting the twins outside during daylight. No more relaxed evenings on the porch.

The twins noticed the change and grew restless. The male paced at night with a low rumble in his chest. The female stood at the door pressing her palm to wood as if feeling the grain, as if measuring distance through matter.

This is when the story starts to tilt: the cabin is no longer a sanctuary. It becomes a containment facility.

And containment, he learns, changes the contained.

7) The Bigfoot Rumors—And Why He Says They’re Wrong

A week later, in town, he heard two men at the hardware store laughing about Bigfoot sightings near Mirror Lake.

“My cousin swears he saw something moving through the trees.”

“It walked on two legs but wasn’t human.”

They laughed, but the laughter had an edge.

People wanted to believe.

He bought extra padlocks for the shed.

He started keeping the twins inside at night, even though they hated it. The male destroyed a chair in protest—ripped it apart with his hands. The narrator didn’t yell. He cleaned it up and reinforced the door latch.

His journal from that period fills with a kind of dread that reads like the onset of inevitability: they were getting too big, too strong, too smart.

By May, he writes, the male was nearly six feet tall. The female smaller but faster, more agile.

When they moved through the cabin, floorboards creaked.

When they breathed, you could hear it across the room.

He thought about options: wildlife rehabilitation centers, research facilities, universities. But every scenario ended in cages or worse.

So he did nothing.

He kept feeding them.

He kept hiding them.

He kept lying.

“People talk about Bigfoot like it’s a joke,” he wrote. “But that’s not what they are. I never believed the stories. Still don’t. Not really. They’re something else entirely.”

If this reads like rationalization, that’s because it is. He needed “something else” because “Bigfoot” carried a cultural machinery—hunters, fame, money, obsession—that would consume them the moment he admitted their existence.

And yet the machinery was coming anyway.

8) Livestock, Blood, and the Moment the House Stopped Being His

June arrived with a wake-up call.

He found his chicken coop torn apart. All six hens dead and mutilated. The door ripped off hinges and thrown twenty feet into the woods.

Then one goat vanished. He found her three days later half-eaten, dragged into a ravine a quarter mile from the cabin.

The second goat disappeared a week after that.

Tom stopped by when he heard, said he’d lost chickens too. The sheriff’s office sent a deputy around to ask if anyone had seen anything unusual.

The narrator told him no.

Kept his face neutral.

The deputy left a card anyway.

He knew it was the twins. The male had been getting out at night somehow, and he suspected the female went with him. He’d wake to find them gone, then returning before dawn smelling of blood and forest.

When he confronted them—pointing, raising his voice in a way he now calls “clumsy”—they stared back. The male made a sound he’d never heard before, almost like speech. It made his skin crawl.

This is the turning point where affection collapses into fear: the moment the caretaker realizes the beings in his home have their own agenda.

9) The Knocks

Then came the knocking.

Three knocks on the cabin wall around midnight, always the same rhythm. At first, he tells himself it’s coincidence—branches, animals, wind.

But the pattern holds. Midnight or 3:00 a.m.

Three precise hits.

Soon the knocks are violent thuds that shake walls. Scratches appear near the handle. He reinforces the door with a 2×4.

Food disappears in quantities that no human—let alone one man—could explain away. His pantry is systematically raided. A twenty-pound bag of rice vanishes overnight. Canned goods. Dried meat. Frozen venison. Even emergency supplies.

He restocks; it disappears again.

He finds some cans stacked in the woods, lids peeled back with disturbing precision.

“They were stealing everything,” he wrote. “Preparing for something.”

He starts drinking more. Bourbon in coffee, whiskey before bed. It doesn’t help.

One night he forces himself outside. He finds them sitting on the porch side by side, watching darkness as if it were a screen.

The female looks at him and he swears he sees pity in her eyes.

Or warning.

He goes back inside without speaking.

10) The Footprint That Made Denial Impossible

In September, just before the seventh anniversary of finding them, he finds the first footprint by his water system.

Seventeen inches long. Humanoid. Five toes. Clear arch. Heel strike that shows weight distribution.

He kneels in mud with his hand shaking.

“This wasn’t some ambiguous track that could be explained away,” he wrote. “This was undeniable.”

More prints appear around the cabin, to the shed, into the forest and back. He tries to erase them with a rake.

They keep reappearing.

Like they want him to see them.

Like they want him to understand the locks and rules mean nothing now.

Then he sees the male fully in daylight—fifty yards away, standing between two cedars, upright, broad-shouldered, hair catching afternoon light.

Not hiding.

Not moving.

Watching.

He drops the bucket. Water soaks into ground. They look at each other for thirty seconds that feels like an hour. Then the male steps back into shadow and is gone.

That night he hears them “talking”—the rhythm and cadence of language. He presses his ear to the bedroom door.

It sounds like negotiation.

Planning.

Then three knocks from the female—on her side of the door.

He knocks back out of old routine.

She makes a sound that could be acknowledgment—or something else entirely.

A shadow passes his window, too tall to be her.

The male is outside again.

And this is where his confession becomes darker: he opens his photo gallery and sees seven years of documentation—infants, toddlers, juveniles, adolescents, adults—proof of what they are and what he did.

He finally lets the forbidden word form fully in his head:

Bigfoot.

The myth people spend lifetimes hunting.

He raised two of them from infancy.

And the moment he admits that to himself is the moment he begins the next betrayal.

He starts making phone calls.