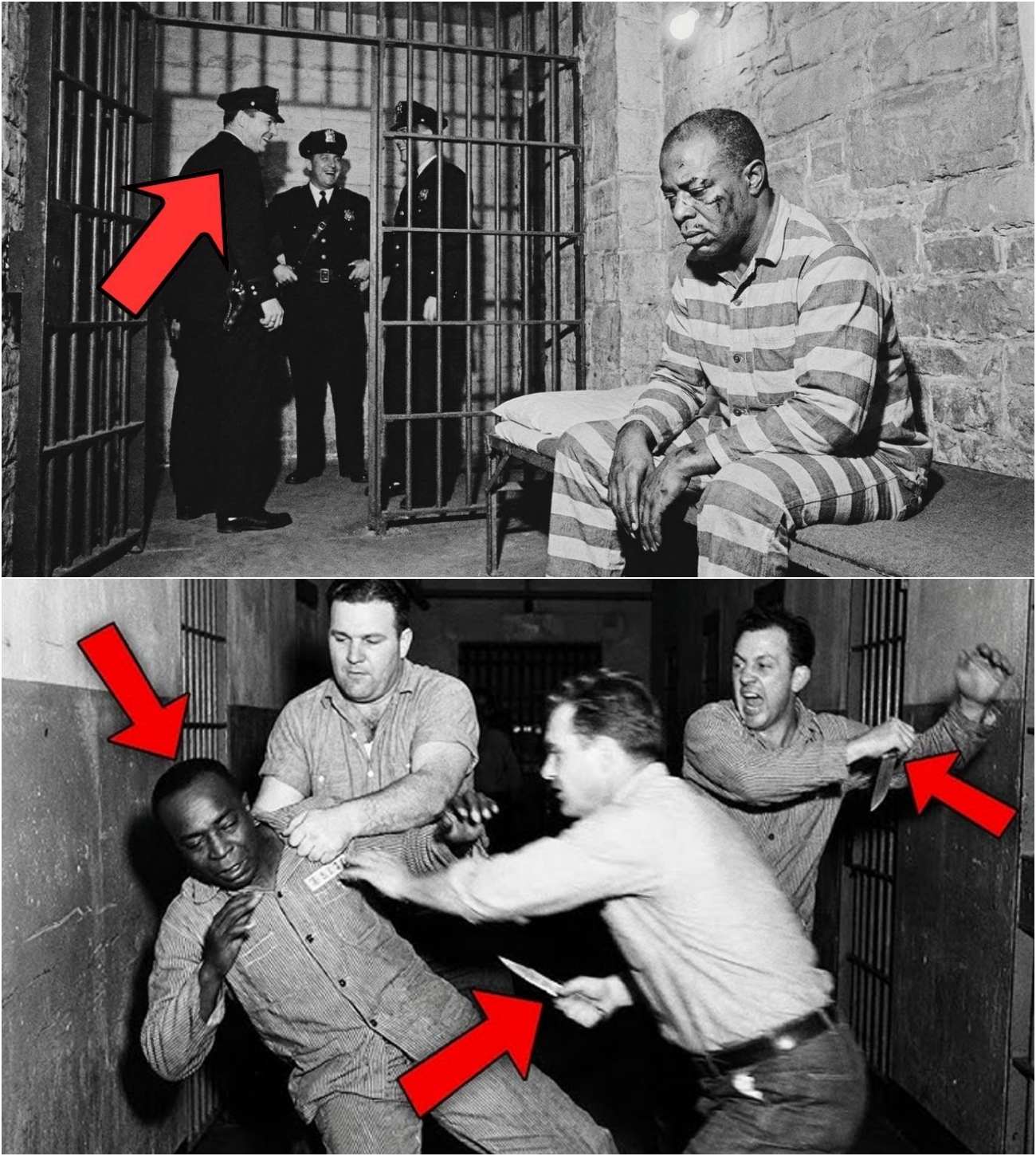

Bumpy Johnson Was Beaten Unconscious by 7 Cops in Prison — All 7 Disappeared Before He Woke Up

On Thursday afternoon, November 12, 1952, the walls of Sing Sing Correctional Facility swallowed a secret that has never fully surfaced again.

At 2:17 p.m., Bumpy Johnson—already eight months into a fifteen-year sentence many believed was politically engineered—was led away from the prison workshop under false pretenses. Minutes later, seven corrections officers cornered him out of sight and beat him with nightsticks until his skull fractured and his body collapsed. He was left unconscious, bleeding, and presumed finished.

By dawn, Bumpy Johnson was alive.

The seven men who beat him were gone.

What followed has been whispered for decades in Harlem barbershops, prison tiers, and police hallways—not as a court-proven fact, but as a legend so persistent it changed behavior. The story’s power lies less in what can be proved than in what it convinced people to believe.

A PRISON BUILT ON FEAR

Sing Sing in the early 1950s was not a place for restraint. Guards ruled by intimidation; complaints vanished with paperwork. Racial abuse was common, and violence was tolerated so long as it stayed quiet. Johnson, forty-eight, knew the rules. He kept his head down, planning an appeal and avoiding confrontations that could bury him deeper.

The men who confronted him that afternoon reportedly had reputations inside the walls. They chose a storage corridor where no inmates worked, no cameras existed, and sound didn’t carry. The beating was swift and merciless. When an inmate discovered Johnson minutes later, his face was unrecognizable. The prison doctor recorded severe head trauma and broken ribs. Transfer to a civilian hospital was requested—and denied.

Johnson remained in the infirmary, unconscious.

THE CLOCK THAT STARTED TICKING

Whether by rumor or reality, word traveled beyond Sing Sing with astonishing speed. Harlem had long understood Johnson’s power as redundant—a structure designed to function without him. Lieutenants managed day-to-day business. Couriers carried messages. And a rule existed that everyone knew but no one wrote down: an attack on Bumpy was an attack on the whole organization.

That evening, while Johnson lay comatose, the legend says his people moved.

They didn’t threaten. They didn’t negotiate. They removed.

THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED

Between 11:00 p.m. and 1:00 a.m., all seven guards ended their shifts and headed home—to Yonkers, White Plains, Peekskill, Mount Vernon, New Rochelle. According to the story, each was intercepted separately: a roadside stop, a bar’s back door, a tow-truck ruse, a driveway ambush. No witnesses. No noise.

By midnight, the tale claims, seven men were gone.

Cars were later found abandoned near transit hubs. Families filed missing-person reports. Investigators noticed the coincidence—seven disappearances in one night—but found nothing that held in court. No bodies. No suspects. No proof that connected the vanishings to a single unconscious inmate.

WHEN BUMPY WOKE UP

At 8:23 a.m. Friday, Johnson regained consciousness. He recognized the doctor, answered basic questions, and grimaced through pain. An attorney visited later that morning and delivered the news that would ripple through Sing Sing: none of the seven guards had reported for duty. All were missing.

Johnson didn’t celebrate. He didn’t speak. He simply closed his eyes.

From that day forward, the culture inside Sing Sing shifted. Guards avoided him. Harassment stopped. Whatever the truth, the belief hardened: touching Bumpy Johnson carried consequences that did not require his orders—or even his awareness.

FACT, FABLE, OR FEAR?

Historians and journalists have chased this story for years and reached the same impasse. Records confirm the beating. Records confirm seven guards disappeared the same night. Records do not confirm murder, nor do they place responsibility. The case files went cold. The river yielded nothing.

What can be said with confidence is this: the legend worked. Violence against Johnson ended. The prison learned a lesson—whether taught by reality or rumor—that power doesn’t always need proof to be effective.

THE MESSAGE THAT OUTLIVED THE TRUTH

In Harlem, the story settled into folklore with a simple moral: beat the man into a coma and his shadow will answer. It wasn’t about vengeance; it was about deterrence. Not spectacle, but certainty.

Johnson served years more without incident. Appeals followed. So did releases and returns. Through it all, guards remembered November 1952—not for what they saw, but for what they didn’t.

Seven men walked out after a shift and never came back.

And before Bumpy Johnson opened his eyes, Sing Sing learned the cost of believing a man powerless.