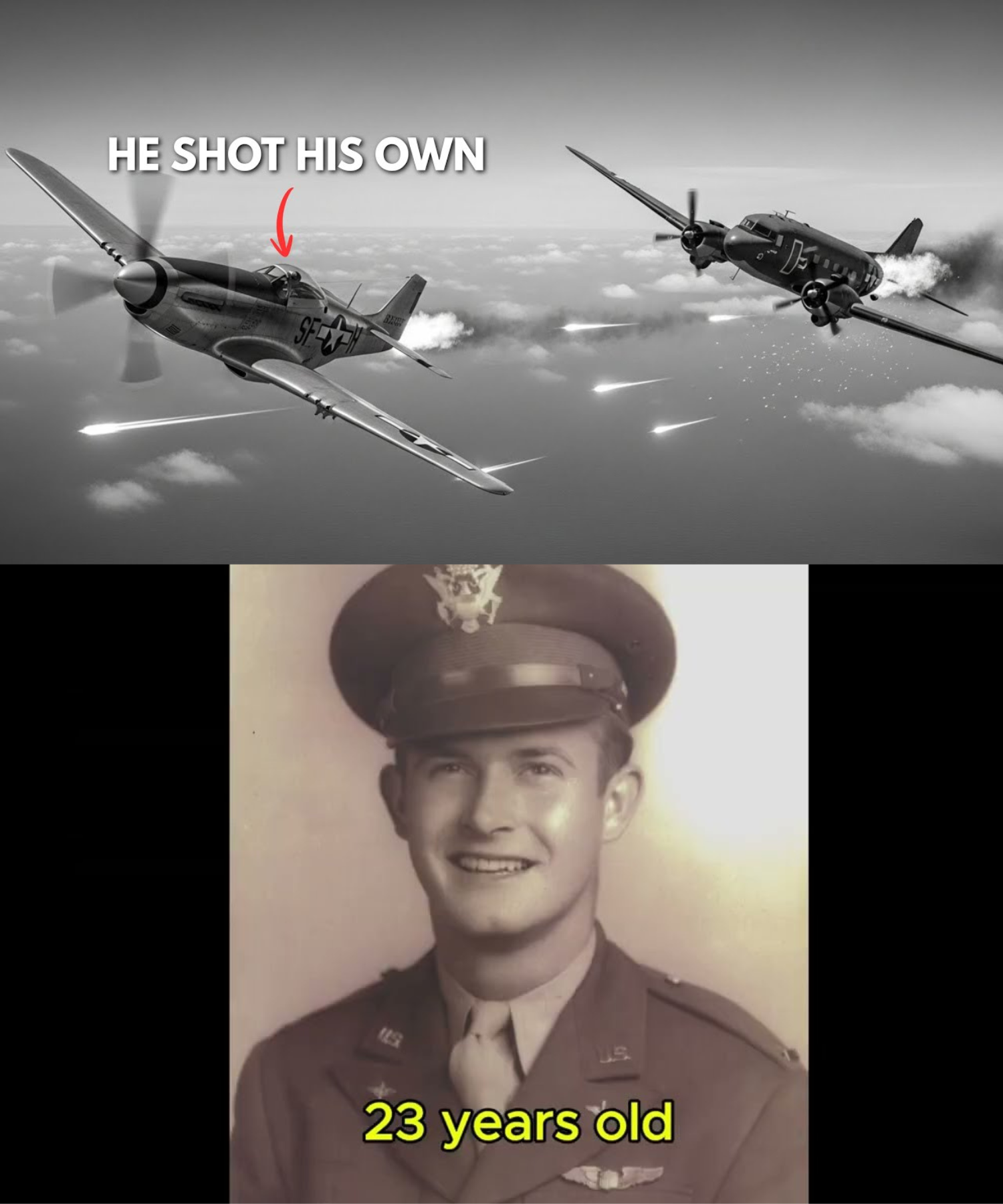

How a US Pilot Shot Down an American Plane — And Got a Medal for It ✈️🎖️

On most days, the rules of war feel brutally simple:

You don’t kill your own.

But war has a way of bending even the clearest lines until they twist into something unrecognizable.

That’s what made Captain Daniel “Hawk” Harlow’s story so unsettling. He was the U.S. fighter pilot who, on a hot, cloudless afternoon over the Persian Gulf, shot down an American aircraft—and walked away from the inquiry with not a court-martial, but a medal.

Depending on whom you asked, he was either:

A hero who made an impossible call that saved hundreds of lives, or

A dangerous symbol of how war lets the system excuse the inexcusable.

The truth, as usual, sat somewhere in the turbulence between.

The Routine Patrol That Wasn’t

It started like dozens of other missions.

Harlow’s F/A‑18 Hornet launched from the deck of the carrier USS Columbia just after sunrise. His assignment was straightforward:

Fly combat air patrol over a designated corridor.

Monitor an American convoy flying troops and supplies inland.

Intercept and identify any unknown aircraft approaching the air route.

The war in the region had dragged on long enough that routine felt dangerous in its own way. Complacency got people killed. Harlow had seen that up close: a missile that should’ve been intercepted, a helicopter that never made it back.

He wasn’t about to add his name to that kind of story.

The sky that morning was a sharp, unforgiving blue. The air‑to‑air radar on his console swept in slow, confident arcs. Voices crackled through his headset:

“Hawk, this is Guardian. You’re cleared to patrol sector Delta‑Three. Convoy Victor‑Seven is inbound on schedule. ROE as briefed.”

Rules of engagement: strict. Identification: positive. Tensions in the region: sky‑high.

Harlow rolled his shoulders, checked his instruments again, and settled in for what he assumed would be a long, slightly boring, deeply necessary watch.

He was wrong.

The Blip on the Radar

He saw it first as a faint flicker on his scope. A contact blinking into existence just outside the designated corridor.

He glanced at the data block:

Altitude: climbing.

Speed: increasing.

Identification: none. No IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) signal.

His brows knit together.

“Guardian, Hawk,” he radioed. “I’ve got an uncorrelated contact at angels two‑zero, heading inbound toward Victor‑Seven’s corridor. No transponder, no IFF. Confirm any flights in that sector?”

Static, then:

“Negative, Hawk. No friendly traffic filed in that area. Stand by.”

Harlow’s thumb hovered near the sensor controls. He nudged his jet slightly toward the contact, narrowing the angle. The blip firmed up. The unknown aircraft was definitely climbing—and angling toward the American transport corridor.

On his tactical display, a ghostly line projected where it was headed.

Right toward the convoy.

“Guardian, that contact’s on an intercept course,” Harlow said. “Request vector to ID.”

“Hawk, you are cleared to investigate. Maintain ROE. Do not engage without positive ID and hostile intent confirmed.”

Positive ID. Hostile intent.

In training, those phrases came with neat diagrams and clear examples. In the real sky, they came with fog.

The First Warning

As Harlow closed the distance, his onboard systems tried to make sense of the approaching aircraft. The computer started pulling in data:

Size: roughly medium jet size.

Heat signature: hot—full power.

Shape: not yet clear.

He squinted at the growing speck ahead.

“Unknown aircraft, this is U.S. Navy fighter on guard frequency,” he broadcast on the emergency channel. “You are approaching a restricted corridor. Identify yourself immediately.”

Silence.

The speck grew.

He waited, then sent the warning again, this time with more edge:

“Unknown aircraft, you are approaching a U.S. military flight path. Turn away now and identify. Failure to comply may result in engagement.”

Still nothing.

The distance ticked down on his heads‑up display.

40 miles.

35.

30.

The contact continued to climb and lean toward the American corridor, like a knife angling toward an exposed seam.

Behind him, somewhere he couldn’t see, a string of transport aircraft—C‑17s and C‑130s stuffed with troops and supplies—drifted through the sky along their designated track. Big, slow, and painfully vulnerable.

Harlow’s jaw tightened. He’d seen what a determined hostile jet or suicide bomber could do to aircraft like that. You didn’t gamble with an unknown speeding toward them with transponder off and radio silent.

“Guardian, Hawk. Unknown is not responding on guard. No IFF. Heading continues toward Victor‑Seven. Time to intercept the convoy: under ten minutes.”

“Copy, Hawk. Attempt visual ID. ROE still in effect. We don’t know what that is yet.”

He nudged his jet into a shallow descent, trading altitude for speed, closing the gap. His radar painted the contact, and his targeting system whispered that it was ready to do more.

But this wasn’t a video game, and he was not eager to pull the trigger.

The Mistake No One Saw Coming

At 20 miles, his tactical display began to gather enough data to give him something else: a silhouette.

What appeared on his systems made his stomach twist.

It looked… familiar.

“Guardian, I have a tentative silhouette,” he said slowly. “Profile resembles a—”

He stopped himself. Couldn’t be.

His mind pushed back against what his eyes and instruments suggested.

“Say again, Hawk?”

He zoomed in, tightening his focus, watching the ghostly outline wobble into more detail.

High-wing. Four engines. Broad tail.

Transport profile.

His heart dropped.

“Guardian…” He swallowed. “Profile matches a U.S. transport. Possibly C‑130 class.”

There was a brief burst of static. When the controller came back, his voice had lost its casual edge.

“Hawk, say again. You’re telling me the unknown matches a friendly transport profile?”

“Affirm. But it’s dark on IFF. No response on guard. Wrong altitude, wrong route, and it’s heading right toward Victor‑Seven.”

The air in his cockpit seemed to thin.

If it was friendly, why wasn’t it squawking? Why wasn’t it talking? Why was it moving like a threat?

There was a short, tense silence on the radio. Harlow knew what was happening: controllers scrambling, checking every flight plan, every manifest, every piece of data that might explain this ghost in the sky.

“Hawk, Guardian. We show no friendly C‑130s in that sector. None. Are you sure about the silhouette?”

He stared at the symbol.

“As sure as I can be at this range.”

“Copy. Continue approach. Obtain visual. ROE unchanged.”

Harlow’s mind ran through possibilities:

A hijacked plane.

A rogue pilot ignoring orders.

A captured aircraft being used as a flying bomb.

Or… a catastrophic comms and transponder failure on a friendly flight that just happened to be in the worst possible place at the worst possible time.

He pushed the throttle forward.

Visual Contact

At 10 miles, the aircraft ahead of him resolved into something more than a symbol. He could see it now: a hulking shape carving through the air, engines bright, wings steady.

He eased slightly above and behind it, the way he’d done a hundred times in training when intercepting unknowns. The sun glinted off its fuselage.

His breath caught.

The paint scheme. The markings.

It was American.

No doubt.

“Guardian, Hawk. Visual confirms: U.S. C‑130 variant. Repeat: American aircraft.”

He half‑expected someone on the radio to shout, to scrub everything, to yell at him to stand down and go home.

Instead:

“Copy, Hawk. We still have no filed flight for that tail. No response to calls on any channel. IFF is cold. And the aircraft is still on vector to intersect Victor‑Seven’s corridor at close range. ROE in effect. You are directive to establish communication and determine intent.”

He set his jaw and slid closer.

From his position, he could see individual windows now. But nothing moved inside that he could make out. No lights flashed a recognition signal. No wing waggle. No course correction.

He tried again, switching to a directed frequency.

“Unidentified U.S. C‑130, this is U.S. Navy fighter on your six. You are heading toward a restricted military convoy. Acknowledge immediately and alter course.”

Nothing.

He inched closer, close enough that if someone peered out a side window, they could have seen him. He rocked his wings—an international signal: you, respond to me.

The C‑130 flew on, indifferent, like a sleepwalker approaching an open balcony.

The Countdown

“Guardian, Hawk. No joy on comms. No visual acknowledgment. Aircraft remains on collision vector with Victor‑Seven corridor.”

His display showed a convergence point approaching like a closing fist. If the C‑130 continued on its current heading, it wouldn’t just “pass near” the convoy; it would cut straight through the same airspace, close enough that any sudden maneuver or hostile act could be catastrophic.

“Estimate time to corridor entry?” Guardian asked.

He checked his numbers.

“Under four minutes.”

“Time for convoy to clear?”

“Longer.”

Static crackled.

He knew what they were thinking. Hundreds of troops and aircrew aboard those transports. One unknown aircraft, unresponsive, at full power, on a path that made no operational sense.

“Hawk,” Guardian said, slower now. “We are still unable to identify or contact that aircraft. Possibility of compromise or hostile control cannot be ruled out. ROE authorizes engagement if hostile intent is determined.”

Only Harlow could see what “hostile intent” looked like up here.

He studied the big plane’s behavior. No evasive moves. No distress signals. Just a steady, relentless line into the path of the convoy.

“You still see no course change?” Guardian asked.

“Negative.” He forced his voice to stay level. “I have repeated warnings and signals. No response.”

He imagined what might be happening inside the C‑130:

A hijacker holding a gun to the pilots’ heads.

A suicide team that had killed the crew and locked the controls.

Or a cockpit full of unconscious Americans, overcome by some silent failure, the plane now nothing more than a heavy missile guided by inertia and momentum.

There was no way to know. Not in the time he had left.

“Two minutes to corridor entry,” he reported.

The silence on the radio now felt like a pressure on his ribs.

Then:

“Hawk.” Guardian’s voice had changed. It carried the weight of decision now. “You are weapons free if you assess continued flight path as hostile toward Victor‑Seven. This is a lethal engagement decision. Confirm understanding.”

He felt the words like a physical blow.

Weapons free.

He could shoot.

He could also be about to shoot down a plane full of his own people.

“I… copy,” he said quietly. “Weapons free based on my hostile intent determination.”

No manual, no matrix, no lawyer was with him up here. Just his training, his fear, his responsibility—and a ticking clock.

The Choice

He flew closer, lining up slightly off to the left of the C‑130, his Hornet a small, sharp shadow next to the lumbering giant.

His targeting system was ready. One thumb movement, a squeeze of the trigger, and the missile would do what it had been engineered to do: find heat, then tear metal and lives into fragments.

His mind split in two.

One half whispered:

You don’t have enough. You don’t know it’s hostile. You might be killing 60 Americans because of a transponder glitch and a busted radio.

The other half answered:

If you are wrong the other way, you’re condemning possibly hundreds more. Those transports cannot dodge a bomb or a ramming.

He stared at the tail of the C‑130, at the American flag painted near the serial number.

His finger floated near the trigger, trembling.

He tried one last time:

“Unidentified U.S. C‑130, this is your final warning. You are about to enter a restricted convoy corridor. Turn away now or you will be fired upon.”

The engines roared. The plane did not.

“One minute to corridor,” he said.

Something inside him snapped into focus. There was no time left for hope, only for choice.

“Guardian,” he said, voice steady now. “Based on failure to respond, no IFF, no filed flight, and continued intercept course to Victor‑Seven, I am declaring this aircraft hostile by behavior. I am engaging.”

There was a pause.

“Copy, Hawk,” Guardian said quietly. “Engage.”

He breathed in. Out.

Then he pressed the trigger.

Impact

The missile left his wing with a sharp shove and a brief, violent flash. For a second, it looked almost slow, like a toy drifting through a calm sky.

Then it streaked ahead, corrected its path, and slammed into the left wing root of the C‑130.

The explosion was brutally bright. Flame tore from the wing like a sudden flower. The engine shredded, a storm of jagged metal spinning out into the blue. For a moment, the aircraft lurched but stayed together.

Harlow felt his gut lurch with it.

“Come on,” he whispered, not sure what he was hoping for anymore.

The C‑130 began to roll, slowly at first, then more violently. Smoke streamed behind it. Debris peeled away. Eventually, the big aircraft could no longer pretend to be a plane; it became a falling object.

He watched it spiral toward the distant haze of the desert below, a slow, tragic tumble. No parachutes appeared.

His throat tightened.

“Guardian, Hawk. Splash one…” He swallowed. “Friendly profile.”

The radio was quiet longer than it should have been.

“Copy splash,” Guardian said finally. “Convoy Victor‑Seven is altering course. You are to return to base. Stand by for debrief.”

Harlow stared at the empty patch of sky where the aircraft had been moments before.

The flag on its tail seemed burned into the back of his eyes.

The Inquiry

Back on the carrier, the air that filled the briefing room was colder than the outside air.

Senior officers sat at a long table, their faces carefully neutral. Behind them, a screen showed radar tracks, timelines, and annotated maps. At one end sat a lawyer from the Judge Advocate General’s office, lips pressed into a thin line.

Harlow sat alone in a chair facing them. He’d been here before in other contexts, offering testimony after engagements, explaining what he’d seen. But nothing like this.

“Captain Harlow,” the lead officer began. “Walk us through your decision from first contact to engagement. Speak clearly. Everything is being recorded.”

He did.

He described:

The first radar blip.

The lack of IFF.

The silence on guard frequency.

His visual confirmation of an American aircraft.

The unchanging heading toward the convoy.

The repeated warnings.

The authorization of “weapons free.”

The final call.

Occasionally, one of the officers stopped him to ask:

“At that point, did any new information arise that should have altered your assessment?”

“Did you consider the possibility of equipment failure?”

“Explain why you interpreted course maintenance as potential hostile intent.”

He answered as best he could, his voice flat, his mind replaying the sight of the tumbling aircraft over and over.

Later, they showed him what they had pieced together from other data.

The downed plane had been:

A U.S. C‑130 requisitioned for a last‑minute medical transport.

Loaded with wounded personnel being moved to a different surgical facility.

Not properly registered in the primary air tasking order due to a cascade of clerical and communications failures.

Flying with a malfunctioning transponder and partial comms outage.

It was, in other words, exactly the kind of nightmare scenario that no one plans for until it’s too late.

“Was there any way for that aircraft to have known about the convoy corridor?” Harlow asked quietly.

“Unclear,” one of the officers said. “But its flight path was in fact going to intersect the corridor at close range.”

“So I was right,” he said hollowly. “About the hazard. Just not about the intent.”

No one answered.

The inquiry lasted days. They dissected his radio calls, his flight path, his tone of voice. They pulled simulator logs to compare his decision-making under pressure. They ran “what if” scenarios, though everyone knew the real “what if” could never be resolved:

What if he hadn’t fired?

Would the C‑130 have drifted through harmlessly, a tragic but survivable oversight? Or would it have collided, been used, or reacted in some way that turned a near‑miss into a mass casualty event?

No one could say. The only thing certain was this:

He had killed Americans.

And yet, the more they probed, the more a brutal logic asserted itself: given the information he had at the time, his decision had not been irrational. It had followed the rules they themselves had written.

Finally, the lead officer cleared his throat.

“Captain Harlow. The panel has reviewed your actions. We find that you complied with the rules of engagement as they were presented and understood. We find no criminal negligence in your decision to engage.”

Harlow stared at him.

“So that’s it?” he asked. “It was… fine?”

“‘Fine’ wouldn’t be the word I’d use,” the officer said quietly. “But from a legal and operational standpoint: you did your duty as you understood it in a compressed, high‑risk scenario. The failures here were systemic, not individual.”

Someone slid a folder across the table.

“You’ll be redeployed after a period of stand-down and evaluation,” another officer added. “There is also…”

He hesitated, as if the next words tasted wrong.

“There is also a recommendation for formal commendation—a medal—for your decisiveness under extraordinary circumstances.”

Harlow blinked.

“A medal,” he repeated.

“For what, exactly?”

The Medal

The ceremony was small. No families, no speeches about glory. Just a scattering of uniforms on the carrier deck under a sky that had the decency to be overcast that day.

A citation was read:

“For exceptional judgment and decisive action in defense of U.S. forces under imminent threat, Captain Daniel Harlow did…”

The words blurred in his ears: imminent threat… difficult decision… protected the convoy… likely prevented greater loss of life…

He stood at attention while a small, heavy piece of metal was pinned to his chest.

The applause that followed was subdued. His squadron mates clapped, some with genuine admiration, some with eyes that slid away from his.

Later, in the relative privacy of the ready room, his closest friend, Lieutenant Marcus Chu, sat across from him.

“You know why they did it, right?” Chu said.

“Because they think I’m a hero?” Harlow’s voice was dry.

“Because they’re terrified of the alternative narrative,” Chu replied. “If they punish you, they admit the system left you hanging with impossible rules and bad information. This medal says: the system works. Even when it clearly doesn’t.”

Harlow looked down at the ribbon and metal.

“Tell that to the families,” he said softly.

The Families

They did.

Eventually, he met some of them.

Not because the system insisted on it—if anything, the system would have preferred to keep all parties buffered by layers of bureaucracy—but because one of the families demanded it, and someone up the chain decided it might be “cathartic.”

He met them in a quiet room stateside: a mother and father, their faces drawn tight; a young woman with the posture of someone who hadn’t yet decided whether she was allowed to collapse.

Their son, husband, brother had been on the C‑130. A medic. He’d survived two roadside bombs, a base mortar attack, and a helicopter with an engine fire.

He hadn’t survived his own flag’s missile.

Harlow walked in with his dress uniform on and his medal starkly visible on his chest. He almost took it off at the door. Almost.

The mother stared at it for a long time.

“You shot him down,” she said eventually, her voice remarkably steady.

“Yes, ma’am,” Harlow said. “I did.”

“You got a medal,” she added, eyes never leaving his.

“Yes, ma’am,” he repeated.

Silence hung between them like a loaded weapon.

Finally, the father spoke, his voice rusted from disuse.

“Tell us why,” he said. Not angrily. Just as a request from someone trying to assemble a shattered picture.

So Harlow did.

He described the radar contact, the lack of response, the unknowns, the converging flight paths.

“I believed,” he said, “that if I didn’t act, the aircraft your son was on might be used—intentionally or not—in a way that would kill many more people. I believed I was sacrificing a smaller number to prevent a larger catastrophe. I can’t know if that belief was correct. I only know that I had seconds to decide, and I made the call I thought would save the most lives based on what I had.”

The room was so quiet he could hear the clock.

The young woman—sister or wife, he wasn’t sure—finally spoke.

“Do you sleep?” she asked.

He met her eyes.

“Not as much as I used to,” he said.

She nodded, a small, bitter acceptance.

“My brother used to say the same thing,” she murmured. “Before he ever got on that plane.”

The mother’s eyes had filled with tears at some point without her noticing.

“I don’t know if I forgive you,” she whispered. “I don’t know if I can. But I’m… starting to understand that you were not the only one who failed him.”

Harlow felt something in his chest loosen and then twist tighter than before.

“For whatever it’s worth,” he said quietly, “I’ve never thought of that day as a success. I think of it as the day the system forced me to choose which Americans died.”

What the Medal Means

Years later, journalists would discover the incident through leaked documents and anonymous sources.

The headline practically wrote itself:

HOW A US PILOT SHOT DOWN AN AMERICAN PLANE — AND GOT A MEDAL FOR IT

Outrage followed. Some commentators demanded his head. Others praised him as a tragic hero. Politicians used the story as a cudgel against their opponents:

“This shows how broken our military bureaucracy is.”

“This proves our rules of engagement are either too strict or not strict enough.”

“This is why we need better technology / stricter oversight / more training / fewer wars.”

Almost no one seemed interested in the strange, awful nuance: that sometimes, war pins medals on people for decisions that feel like moral injuries rather than triumphs.

By then, Harlow had left active duty. The medal sat in a drawer, not on a wall. He worked as a flight instructor, teaching young pilots the same split‑second judgment the world had once demanded of him.

Every so often, one of them would ask:

“Sir, would you do it again? If you were back in that cockpit with the same information?”

He would pause, then answer with painful honesty.

“I don’t know,” he’d say. “I know what I did, and I know why. I also know I live every day with the possibility that I killed people I didn’t have to kill. That’s the part the citations don’t talk about.”

Then he’d add, more quietly:

“But I do know this: the real failure wasn’t in the cockpit. It was everywhere that allowed me to face a choice where every option was wrong.”

The Story Behind the Headline

On paper, the story is simple:

A U.S. pilot shot down an American plane.

The military gave him a medal.

In reality, it’s a mess of:

Bad data and late paperwork.

Faulty transponders and dead radios.

Strict rules written for clarity and applied in chaos.

Human judgment squeezed into seconds that will haunt someone for decades.

The medal pinned to Harlow’s chest didn’t mean, “You did something good.”

It meant, “We’re officially calling what you did necessary.”

Whether it truly was—or whether it was just the least terrible choice in an impossible moment—is a question that can’t be answered by inquiries, citations, or headlines.

Somewhere, a folded flag sits on a mantle because of his decision. Somewhere else, hundreds of other families never got that flag because of the same decision.

That’s how a U.S. pilot shot down an American plane—and got a medal for it.

Not because it was right.

Because in war, sometimes “right” disappears, and all that’s left is who bears the weight of the least wrong choice.