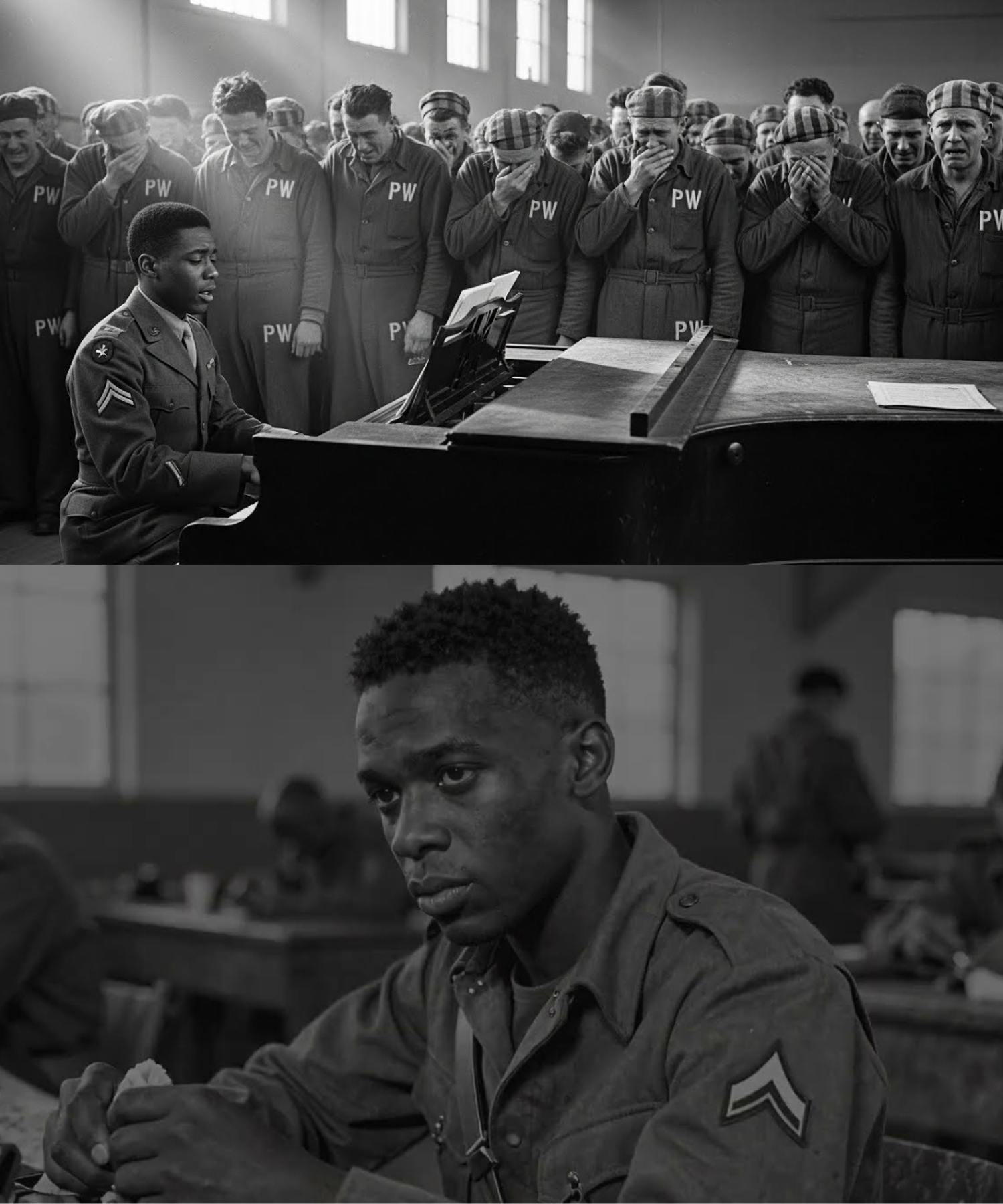

🎹 When a Black Soldier Sat at the Piano — What He Played Made the German Prisoners Weep

The piano wasn’t supposed to be there.

Camp Hartsfield had been assembled from whatever the Army could claim and convert: a former boarding school on a hill, a few long barracks buildings, a mess hall that smelled like boiled coffee, and fencing that made the wind sound like a constant warning. The piano sat in the assembly room of the old schoolhouse—upright, dark wood, scuffed corners—left behind when the students fled and the world changed hands.

It survived the transition the way certain objects do: by being too heavy to move and too familiar to destroy.

Most days, it was silent.

The German prisoners of war were marched past it during headcounts and medical checks. They were fed, counted, returned. No one in authority cared whether a piano existed in the corner of a war’s paperwork. If anything, it felt like a joke—an instrument meant for recitals now trapped inside a camp where men learned not to hope too loudly.

But sometimes, at dusk, when the air cooled and the guards grew tired of their own voices, the silence inside that room felt like it had a pulse.

The Soldier Who Kept His Hands to Himself

Private First Class Isaiah Reed didn’t talk about music.

The other soldiers knew him as steady and sharp-eyed, the kind of man who cleaned his rifle as if it were a ritual and folded his spare socks with the precision of someone who couldn’t control much else. He was assigned to camp support—security rotations, supply runs, paperwork deliveries—jobs that made you invisible until you made a mistake.

He was also Black, which meant invisibility came with extra rules.

Reed had learned early that attention was a currency. In some rooms, he couldn’t afford it. In others, he couldn’t escape it. He moved through the camp with a calm that was not the absence of feeling, but the careful management of it. He spoke when necessary, smiled rarely, and kept his hands—especially his hands—busy with tasks that didn’t invite questions.

Those hands, however, carried a secret.

He had grown up with a battered upright piano in a church basement in Georgia, where the keys stuck in summer and the pedal groaned like an old man standing up. He learned to play because the pastor noticed the way he listened—head tilted, eyes narrowed—like he was trying to locate something in the air. Music, it turned out, was that “something.”

Later, when he enlisted, he told no one.

A soldier with soft skills could be treated as soft. A soldier who revealed joy could have it taken.

So Reed kept his gift quiet, tucked away like a letter you don’t open until you’re safe.

The German Prisoners and the Weight of Quiet

The German POWs at Hartsfield were not the snarling caricatures Reed had imagined in propaganda reels. Some were young, barely men, their bravado melted into fatigue. Some were older, the sort who carried themselves with a strictness that looked like pride but felt more like refusal to collapse.

They were guarded, but they were also watched by their own shame.

Prisoners learn quickly what not to show. Regret could be mistaken for weakness. Weakness could invite ridicule. Ridicule could become a fight. A fight could become punishment. So most of the men kept their faces neutral and their voices low.

They developed habits: the same routes across the yard, the same quiet trades of cigarettes for buttons, the same careful avoidance of the assembly room where the piano sat like an accusation.

And then, one evening, something changed.

Not with an announcement. Not with an order.

With a sound.

The First Notes

It began on a Sunday, after a long rain that left everything smelling of wet wood and rust. Reed was delivering a stack of forms to the administrative office when a door down the hall stood open. The assembly room was empty. The piano was there, waiting in the corner.

He paused.

He didn’t know why, exactly. Maybe it was the quiet. Maybe it was the way the rain made the world feel like it had been rinsed. Maybe he was simply tired of being only what the war demanded.

He walked in and sat on the bench. It creaked under his weight, an old sound in a new war.

For a moment he did nothing.

Then he placed his fingers on the keys—not dramatically, not with flourish—and pressed down gently, as if asking permission.

The first chord was imperfect. The piano was out of tune in places; one key had a slight rattle. Reed adjusted without thinking, compensating the way experienced players do, bending his touch around the instrument’s flaws as if they were part of its personality.

He began to play.

It wasn’t a marching song. It wasn’t a patriotic anthem. It wasn’t the kind of music that demanded applause.

It was something quieter: a slow, layered progression that felt like walking through memory—simple on the surface, but carrying an ache underneath. Notes rose, fell, and rose again, each phrase answering the last like a conversation between the man he was and the boy he used to be.

Outside the room, boots paused.

A guard stopped mid-step, confused.

Down the corridor, a German prisoner waiting for roll call turned his head sharply, as if the sound had grabbed him by the collar.

An Audience That Didn’t Mean to Listen

Word moved through the camp the way wind moves through wire: fast, invisible, impossible to stop.

Within minutes, a handful of guards were clustered near the doorway, pretending they were there for security. A few German prisoners, lined up for a work detail, shifted their stance so they could hear better. They didn’t look directly into the room. They listened like thieves.

Reed kept playing.

He didn’t glance up. He didn’t acknowledge them. He let the music be the only thing speaking.

The melody grew more intricate—not showy, just honest. It wandered into minor tones that sounded like dusk. Then it lifted into something brighter, a brief window of warmth, before returning to that steady, aching center.

The guards, who had been trained to project authority, fell into an unfamiliar stillness.

One of them muttered, “Where’d he learn that?”

No one answered.

The prisoners stood with their hands clasped behind their backs, faces fixed forward, as if they were not listening at all. But their eyes—some narrowed, some unfocused—betrayed them. They were elsewhere. Somewhere not fenced.

The Man Who Couldn’t Hold It In

Among the prisoners was a man named Otto Keller.

He had been an artillery radio operator. That fact was written on his intake form in neat English letters, as if the name of a role could capture the shape of a life. Keller was in his late thirties, with a careful moustache he trimmed even in captivity, and hands that never stopped moving—tapping, rubbing, folding—like they were searching for work that didn’t exist.

He had not cried when he was captured. He had not cried when he was marched into camp. He had not cried when he received news—delivered without cruelty, just fact—that his home city had been shelled.

He had cried exactly once in the war, alone, behind a shed, where no one could see.

When Reed’s music reached a certain sequence—an unresolved line that hung in the air like a question—Keller’s posture shifted. His shoulders, usually rigid, dropped a fraction.

Then his face tightened.

Not with anger. With effort.

The music did something the camp could not: it made space for feeling without asking permission.

Keller stared at the floorboards. His jaw worked as if he were chewing something bitter. His eyes watered, and he blinked hard—too hard.

A tear escaped anyway.

Then another.

He pressed the heel of his hand to his face, ashamed, as if tears were contraband.

But the sound kept coming—patient, steady, unafraid of him.

Keller’s breathing stuttered. His lips trembled. And then, in a way that surprised even him, he began to cry openly, shoulders shaking in small, contained waves.

The prisoners nearest him noticed first. One looked away quickly, as if to respect privacy. Another glanced at him and then—after a hesitation that lasted a lifetime—placed a hand lightly on Keller’s elbow.

Not to stop him.

To steady him.

The Room That Changed Without Permission

A German prisoner crying in front of American guards should have been humiliating. It should have been dangerous.

Instead, the moment hung there, fragile and strange, and no one smashed it.

The guards didn’t laugh. They didn’t bark orders. They didn’t rush in to restore “discipline.”

They simply listened.

Because the sound coming from the piano did not belong to victory or defeat. It belonged to something older than uniforms: the human need to mourn what you cannot fix.

Reed, still not looking up, shifted into a different piece—not a new tune so much as a new mood. He played chords that sounded like a lullaby remembered from far away. The melody softened. The rhythm slowed as if it were trying to comfort the room without embarrassing it.

Keller’s tears became quieter. He wiped his face with the cuff of his sleeve and stared toward the doorway, eyes red, expression raw.

Another prisoner swallowed hard, blinking rapidly.

Then another.

Not all of them cried. But the room changed. The way men stood. The way they breathed. The way they stopped pretending.

A Guard’s Problem

Sergeant Callahan, the senior guard on duty, finally stepped into the assembly room.

He had a problem. Not because a soldier was playing music—morale programs existed, after all—but because the camp ran on separation. Us and them. Keeper and kept. Winner and captured. Those lines made a system feel stable.

The piano blurred the lines.

Callahan stood behind Reed and watched his hands.

Reed’s fingers moved with quiet authority, not rushing, not hesitating. There was no theatrical bouncing, no “look at me.” Only a man speaking in the language he trusted most.

Callahan cleared his throat, a sound that would normally end any conversation.

Reed did not stop playing.

Callahan waited, then said more softly than he intended, “Private Reed.”

Reed’s hands kept moving. He nodded once, acknowledging the name without surrendering the music.

Callahan hesitated again, then—like a man stepping onto thin ice—asked, “How long you been playing?”

Reed’s voice was low, almost swallowed by the notes.

“Since I was a kid.”

Callahan looked at the watching prisoners. The rawness on their faces made him uncomfortable in a way threats never did.

He could end it with a command.

Instead, he said, “Finish the piece.”

Reed nodded again.

And the camp, without anyone filing a request, gained an unspoken rule: the piano could speak, sometimes, when words would only make things worse.

The Request Nobody Wanted to Make

The next evening, Reed returned.

Not because he had been ordered. Because he had slept poorly and woke with the music still in his fingers, like a message he hadn’t finished delivering.

He walked into the assembly room at dusk, sat down, and began to play.

This time, the audience was larger.

German prisoners stood at the back, spaced apart, trying to look uninterested. Guards hovered near the doorway, arms crossed, pretending their presence was purely professional.

Reed played with more confidence. The piano’s flaws didn’t bother him anymore; he was used to imperfect instruments. He shaped the sound so it carried.

Near the end of the set, he let the final chord linger—soft, sustained, fading like a candle.

The room stayed silent for a long moment.

Then a voice from the back spoke in careful English.

“Please,” the prisoner said. “Again.”

It was Keller.

He did not sound proud. He sounded human.

Reed didn’t answer with words. He just began another piece—slightly brighter, still tender.

And behind Keller, a younger prisoner—thin, restless—whispered something in German that sounded like disbelief.

A guard who understood enough German translated quietly for himself, face tightening:

“He said… he didn’t think Americans had music like that.”

Callahan glanced sideways, irritated by the ignorance and unsettled by the truth that the war had taught everyone to believe stupid things about the people they were sent to fight.

The Night Reed Played for Both Sides

The third night was the one people remembered.

The camp had been tense all day. A fight had broken out in the yard over a stolen blanket. One prisoner had been sent to isolation. Guards were short-tempered. Prisoners were quieter than usual.

When Reed sat at the piano that evening, he did not start with softness.

He began with a pattern that sounded like work—steady, percussive, insistent. His left hand laid down a pulse like footsteps. His right hand built a melody on top, climbing, twisting, and returning, as if searching for a door in a locked house.

The music had force, but not aggression.

It was the sound of endurance.

As it went on, something in Reed’s face shifted—his brow furrowing slightly, his mouth set, not angry but focused. He played as if he were telling the truth in a room where truth was hard to hold.

Guards stopped fidgeting. Prisoners stopped whispering.

The piece moved through darkness into a refrain that felt like light breaking through cloud—not triumphant, not naive, but earned.

By the time Reed reached the final minutes, several prisoners were crying—not loudly, not theatrically, but with the kind of controlled grief grown men use when they can’t afford to fall apart.

A guard at the door wiped his eyes quickly and pretended it was the smoke from someone’s cigarette outside.

Callahan stared at the floor, jaw clenched, as if angry that a song could undo the hardness he’d been proud of.

Reed ended with a chord that resolved gently—like a hand placed on a shoulder.

No one clapped.

Applause would have turned it into entertainment. No one wanted that. They wanted it to stay what it was: a brief ceasefire inside the ribs.

After the Music

Later that night, Keller approached the doorway as the prisoners were being guided back to barracks.

He didn’t step inside. Rules were rules.

He looked at Reed and spoke with effort, his English rough but sincere.

“You play like…” Keller searched for the word, then settled on something simpler. “You play like home.”

Reed held Keller’s gaze. He didn’t smile, but his face softened.

“I never been to your home,” Reed said quietly.

Keller shook his head. “Not my home. Home. The idea.”

Reed nodded once. He understood. The war had made “home” into a wound for everyone, just in different places.

Keller swallowed. “I am sorry,” he said, and the words came out as if they cost him real money. “For what was done. For what we did. I don’t know how to say it correctly.”

Reed watched him for a long moment, then answered with a truth that didn’t pretend to solve anything.

“Don’t say it to me like it fixes it,” he said. “Say it like you mean it. Then live like you mean it.”

Keller bowed his head slightly—more respect than submission—and walked away.

What the Camp Learned (And What It Didn’t)

The piano didn’t end the war. It didn’t erase racism. It didn’t turn enemies into friends in a neat, cinematic arc.

Some guards still carried prejudice like a second weapon. Some prisoners still believed lies they had been raised on. Some men listened to Reed’s music and felt nothing but irritation that it made them feel anything at all.

But something had shifted in the camp’s atmosphere.

After the nights Reed played, the German prisoners were quieter—not with fear, but with thought. Guards were less eager to provoke. Small cruelties—unnecessary humiliations—became less common, not because anyone was suddenly virtuous, but because the music had reminded them what a human voice sounded like when it wasn’t shouting.

For Reed himself, the change was subtler.

He slept a little better.

He spoke a little more.

And when he passed the piano during his rounds, he no longer felt like it was a relic trapped behind fences. He felt like it was a door—one he could open, briefly, when the world inside the camp grew too tight.

The Last Evening

Weeks later, orders came down: the prisoners would be transferred to another facility. The camp would be reorganized. The piano would stay.

On the final evening before the transfer, the assembly room filled more than it ever had. Guards crowded the doorway. Prisoners lined the back wall. No one had to be told to be quiet.

Reed played for nearly an hour.

He played slow pieces that felt like goodbye. He played faster passages that sounded like trains moving through night. He played something that began in sorrow and ended in a kind of steady acceptance, as if saying: you can survive what you cannot forgive yet.

When he finished, he lifted his hands and let them rest in his lap.

The room stayed silent.

Then Keller, standing near the back, did something that would have once felt unthinkable. He stepped forward just enough to be seen, placed his hand over his heart, and bowed—not to the uniform, not to the camp, not to America.

To the man at the piano.

A few other prisoners followed, small bows, awkward but sincere.

Reed stood and nodded once in return—no speech, no performance. Just acknowledgment.

The guards began moving people out.

The assembly room emptied.

The piano remained, silent again, as if it had dreamed the whole thing.

But the sound—what it had opened—traveled with the men who heard it. Not as propaganda. Not as a victory song.

As a reminder that even in a place designed to reduce people to categories—guard, prisoner, enemy, Black, German—music could briefly return them to the complicated truth underneath:

They were human first.

And sometimes, that was enough to make a room weep.