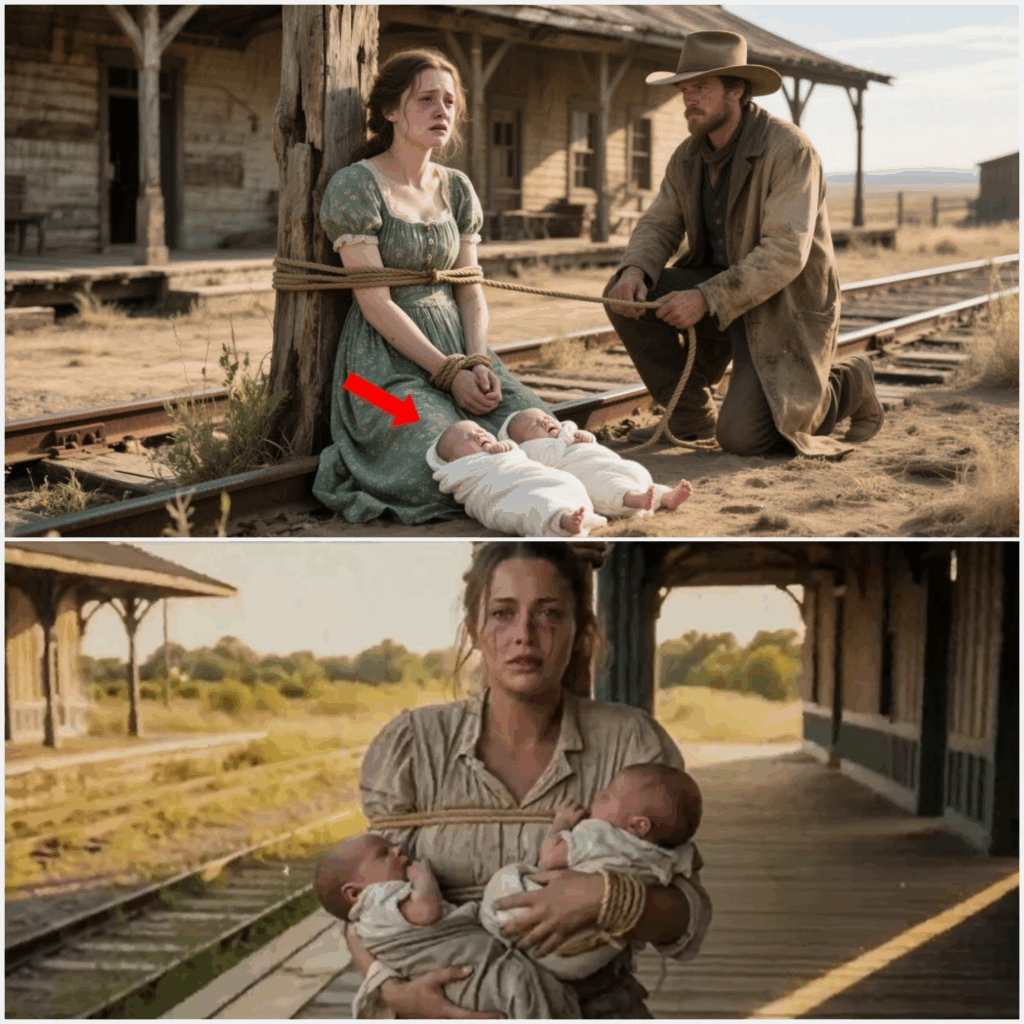

“My Twins Hasn’t Cried In Hours They’re Dying From Thirst”Struggling Rancher Found Tied At Abandoned

.

.

The rails had long since surrendered to weeds, their iron lines eaten by rust, their ties cracked like the bones of an old beast that no one mourned. The station itself stood hollow and gray, its boards warped by forty years of weather, the paint peeled back to bare timber. No train had breathed smoke here in a generation, but still the place held echoes—the ghost whistle of departure, the shuffle of boots waiting for someone who never came.

On that bench beneath the sunburned awning, she lay bound, wrists raw against rope, her body sagging as though every ounce of her had been poured out into the dust. Two small bundles clung to her chest, silent and still, their tiny mouths searching at her skin, only to find nothing. Silence, where there should have been the cry of life. That silence was heavier than the ropes.

He came riding slow, a lean figure astride a gelding with a coat dulled by dust. A man no one would have marked in a crowd, but whose quiet steadiness seemed to draw the horizon toward him. His eyes had the weary knowing of a man who had buried too many hopes under dirt. He had not come looking for salvation, nor even company. He had ridden this way to avoid the road most traveled, seeking a shortcut home across land no one claimed anymore.

The sight of her stopped him the way a bullet does—sudden, absolute, leaving the heart to pound in the stunned silence afterward. At first, he thought her dead, the angle of her head, the stillness of her limbs, the way the air around her seemed already to belong to grief. But then one of the bundles stirred, lips parting, a dry whimper no louder than the buzz of a fly.

He dismounted without a word, boots sinking into the soft drift of dirt that had gathered where men once queued for tickets. The woman’s eyes fluttered open, and in them was not fear, but resignation—the look of someone who had expected the world to pass her by and now believed even rescue would be cruel. He said nothing. Words would have been too heavy in that moment. Instead, he crouched, drew his knife, and cut the rope that had bitten her wrists. The fibers frayed, giving way with a whisper.

She sagged forward, her whole frame trembling. Yet her arms clung instinctively to her infants, though they barely moved against her. He reached into his saddlebag, pulled forth his canteen, and pressed it gently to her lips. She swallowed once, twice, choking on the water as though her throat had forgotten what mercy tasted like. He tilted it then toward one of the babies, letting the smallest drop fall onto cracked lips. The child stirred weakly, and that faint sound, barely more than air, was a miracle in the dying station.

Her mouth moved, forming words without voice, until finally she whispered, “Don’t let them take me back.” The plea carried the weight of a noose, and though he did not know her story, the tone told him enough. The station seemed to hold its breath as he considered her—this stranger with eyes too young to be so hollow. Twenty years, perhaps less, but her skin was roughened by hunger, her hair tangled with dust and shame. She had been left as one leaves trash, cast off where no one would bother to look.

Anger stirred low in his chest—not the kind that burns hot, but the colder kind that hardens into resolve. He lifted her as though she weighed no more than the coat he would have set over a fence. The twins between them pressed close, fragile warmth beneath layers of dust. He carried her to his horse, setting her carefully in the wagon he had trailed behind. She winced, but made no sound, only clutched the infants tighter. He adjusted the reins, slow and deliberate, as though haste might break the thin thread that still held them to life.

The sun dipped, laying long shadows across the forgotten tracks, and as he climbed onto the wagon seat, the air shifted. He could feel her gaze on him—not trusting, not grateful, only desperate, as though she were measuring whether this man too would abandon her once the burden grew heavy. He did not meet her eyes. Some vows are not spoken, but carried in silence, and his silence was steady.

They jolted forward, wheels creaking like old bones, the station shrinking behind them until it was only another ghost on the prairie. He knew little of her yet, neither her name nor the sins the town had written upon her skin. But he knew enough that no one else had come, that she had begged not to be returned, that three lives now leaned into him, fragile as fireflies in a jar.

Night spread itself across the plains, stars pricking through the velvet dark. The baby stirred again, one giving a faint, broken cry that faded back into silence. Her head fell against the wagon’s frame, exhaustion deeper than sleep tugging her down. And though the wind whispered, though the grass shivered, it was her words that clung to him, sinking into his marrow like a brand. Don’t let them take me back. He gripped the reins tighter, jaw set against whatever shadows might be waiting on the horizon. He had not sought this burden, but as the wheels rolled away from the forsaken station, he knew with the certainty of a man who had buried too many dreams that he would not set her down again.

The road slid under the wagon like a slow river of dust, the wheels giving a tired groan each time a rut lifted them and set them back again. Night kept its distance at first, a blue bruise spreading along the horizon while the air held steady and plain—in that ordinary weather, a mercy of calm.

He felt the weight of four lives draw tight on the reins. He had balanced men through stampedes and droughts, but never this quiet burden—a girl hardly grown, two speechless newborns, and the promise he had made with no words at all.

She watched him with the weary stillness of a deer that has learned running only breaks you sooner. Her arms ached from holding the twins, her wrists, mottled and raw, bore the quiet map of what had been done to her. When the wagon lurched, one infant gave a thin squeak that wasn’t yet a cry, and his hand moved by instinct, steadying the smallest bundle as though it were the world’s last coal of heat.

He loosened his coat and padded the boards to soften the ride, then tipped the canteen’s mouth against a clean corner of cloth and touched the damp to each baby’s lips. They rooted weakly, closing their eyes at the taste. The smallest relief—a held breath let go.

He kept the team to a patient walk, feeling every hitch of the wheels translate into her body. She did not speak at first. The night drew out, and the sound of insects turned the darkness into a soft net around them. Only when the road forked did she find a voice, a ragged thread that seemed to fray as it crossed the air.

“Left,” she said, barely more than breath. He turned the wagon without question, trusting the compass that lives in a frightened person’s bones. The plain opened to a scatter of cottonwoods, their leaves clattering like coins, and beyond them the faint line of a creek made a dark seam through the grass.

He drew up beside it and hopped down, the ground cool on his palms as he cupped water for the cloth, then for her. She drank slow, as though she might be punished for wanting, then pressed the damp to each tiny mouth, her hands shaking with the stubbornness of someone learning hope again. He built a little wall of saddle bags to cradle the babies against her, and from an old shirt tore two narrow bands to bind their swaddles snug. His hands were careful the way a carpenter touches the last piece he’ll fit before a house stands.

The girl watched, jaw tight, as if kindness might yet reveal its price. He did not look up, only said, “We’re near my road,” and glanced at the sky where a sigh of moon had lifted, pale as a nail pairing.

She spoke again, a little stronger. Each word found like a coin in dust. “They tied me at the station because I wouldn’t—because I said no.” No names, no places, just the shape of refusal and the bruise of punishment where law had been a mask for hunger.

He listened like a field does, taking what falls without argument. The road lifted toward low hills. Sage brushed the wagon spokes and gave up its clean, bitter scent. Somewhere to the south, a coyote yipped, thin as a hinge, and went quiet again.

He told her what could be told without pride—a lean spread, a few head, fences that needed mending, a roof his hands kept chasing after every wind. “I don’t have much,” he said. “But I have a door that shuts, and a floor that’s clean.”

She nodded once, a movement so small it might have been a flinch, and looked back at the twins, as if measuring whether a simple room could hold a life.

He felt then not heroism, not pity, but the plainest duty—the kind that doesn’t shine, only stands and doesn’t step aside.

The creek ran out and the land turned open again, road truing itself toward a distant rise where cotton spread like a small cloud above his place. He kept talking—a few directions he would take tomorrow, where the water barrel stood, how the stove sometimes smoked if you pushed it too fast. Little practical promises that let a person breathe. She listened, and some rope inside her seemed to loosen, though the marks still ringed her skin.

A metal arc sang from a fence post as if it had opinions about dawn. She smiled, small and sideways, and for a moment her youth came back to her face.

They reached the crossroads by a split rail fence, the kind where news gets hammered in with a nail for whoever wanders past. A tattered paper curled against the wood, flapping once, twice. He hopped down again, tugged it free, and saw the ink. Reward for one young woman, age unmarked, described only by hair, the scar on her wrist, and the twin infants she had borne. A badge drawn in crude strokes stared up like a cheap star.

He didn’t show her right away. He folded the paper small and tucked it inside his coat, then climbed to the seat and gathered the reins as if the leather itself had asked for a firmer hand. Behind them, the fence creaked. Ahead, the road remembered.

The cabin rose out of the land as though the earth had half forgotten it, its walls patched with mismatched boards, its chimney leaning like a tired man. Dust lay thick on the window sills, sifted in by wind that never asked permission. He drew the wagon to a halt, and for a long breath she stared at the place, clutching the twins as if the sight of those sagging beams were another trick, another station that meant abandonment. But he moved with the calm rhythm of a man who knew every fault of the place and had long since chosen to live with them.

Inside, the air smelled of wood smoke and dry earth. The floor was swept clean, though the boards gaped, the table bore the scars of tools, the stove squatted like a black iron heart. He lit a lantern, and the sudden warmth of its glow painted her face soft despite the grime clinging there. She sank onto a stool, too weak to protest when he pressed bread into her hands, thick and stale, but enough to make her eyes water. He set a cup of milk beside her, the last of what his cow had given. She lifted it, trembling, and drank in small swallows. Each one fought for as if shame had to be swallowed, too.

The babies whimpered faintly, lips rooting. He fetched a cloth, soaked it in the milk, and guided her hand to press the damp to their mouths. They fed in tiny, desperate nibbles, and the sound was so fragile he found himself holding his breath as if the world might interrupt if it heard.

Her gaze lifted once toward him, searching, uncertain, but he did not look back. He was hammering silence into the walls, making sure no word would break what was mending in her arms. When she finished, she leaned her head against the table and closed her eyes, crumbs still clinging to her lips.

He studied her then, not as a man studies a woman, but as a farmer studies a crop beaten by hail, measuring if there was still life to coax from the ruin. In her jaw, in the stubborn grip she kept on those children, even while half asleep, he saw the answer.

The next morning, light fell through the cracks like thin spears, catching dust in golden ropes. He stepped outside to fetch boards and nails, and by the time he returned, she was awake, rocking the twins in her lap, her hair falling in knotted strands around their faces. He set the boards down and began working with steady strikes, shaping a crude cradle from scraps once meant for a fence. She watched, silent, as each nail drove in. The sound filled the cabin, sharp against the hush of dawn. When at last he lifted the finished piece toward her, she traced the rough edges with her fingers, her face unreadable until a single tear slipped free. She set the babies inside, their limbs twitching against the wood, and the cabin seemed for the first time to breathe.

Later, he saddled up and rode toward town, needing flour, salt, a strip of cloth. The general store smelled of kerosene and dust, shelves lined with jars of beans and pickled beets. The widow who kept the place peered at him over her spectacles. “You’ve taken company, I hear,” she said, sliding the bag of flour across. Her tone made company sound like sin. Two men near the stove chuckled, trading looks that crawled like flies.

“A woman with twins left at the station,” one muttered. “A man will pick up anything if he’s desperate enough.”

He said nothing, only laid coins on the counter. Silence had always been his weapon, and he wielded it now, steady and unflinching. But the words clung like burrs. When he stepped back into the daylight, he felt them sticking to his skin, waiting for her ears.

The ride home was long, the sun leaning hard against his back. When he pushed the door open, the twins stirred in their new cradle, and she was humming low, a tune without shape, as if she were trying to remember what comfort sounded like. She stopped when she saw him, shame flickering in her eyes as if she’d been caught stealing peace. He set the sack on the table and began to put things away. She touched the babies’ cheeks, whispering something he could not hear. The sound was thin, but it was more alive than any sermon he had ever endured.

That evening, he sat by the stove mending a harness while she tore small pieces of bread to soak in warm milk. The twins’ lips, once cracked and silent, now smacked faintly in the glow of the lantern. He looked up once and saw her staring at the cradle with such fierce longing that it seemed to pierce through every scar that bound her. The cabin’s walls, dust and all, had taken on the shape of safety. But when she lifted her head and met his eyes, her mouth trembled.

“They’ll come,” she whispered, voice brittle as glass.

For a moment he thought she meant hunger or sickness. Then he remembered the paper folded in his coat, its inked badge staring like a curse. He laid down the harness and let the silence fall heavy because promises given too soon break like cheap nails. She turned back to the cradle, shoulders drawn tight as though bracing for a knock on the door that had not yet come.

Sunday dawned clear. The sky rinsed pale as if the night had been scoured of every star. The rancher hitched his team while the cabin still held the faint smell of ashes, and she, holding the twins close against her, stepped into the sunlight with a weary tilt of her chin. The little ones had found their voices at last. Faint cries stirred in their throats, living proof that thirst had not carried them into silence forever. Yet for every sound of life, she seemed to draw tighter, as if the world would punish her for making it.

The wagon rolled toward town at a steady pace, its wheels tracing grooves through the dust that had been carved by generations before them. The rancher did not speak much, only offered his arm when the road jostled too hard. She sat with the children nestled in her lap, eyes darting over the horizon, wary of every rise and shadow. He saw the tension in her, the way her shoulders lifted each time another rider appeared in the distance. He wanted to tell her no one would take her from that bench again, but his words had always been poor tools. So he gave her silence, and the silence was steady.

The town met them with the same sharpness it always gave strangers. Sunday meant church bells and the wooden steeple leaned above the rooftops, its single bell calling out with a tone both holy and hollow. Families filed along the boardwalk, men in clean shirts, women smoothing their dresses, children tugging at hems. When the rancher helped her down, she felt every eye lean toward her, then toward the swaddled infants. A hush followed them like dust in the air, broken by the hiss of whispers.

“She’s the one from the station,” someone muttered near the livery. “Already shacked up at his place,” another voice added. “Low, but not low enough.” “Bought more like,” came the sharper whisper, carrying the sting of laughter.

Her cheeks burned, though the day was cool. She clutched the twins closer, wishing she could fold herself around them until no gaze could pierce. The rancher heard it all, too, but his stride never faltered. He walked beside her with one hand steady at her back, guiding her up the steps into the dim church where the air smelled of pine boards and old hymnals.

Inside, judgment still followed, but here it had softer shoes. Women glanced at her hair, tangled and uneven. Men shifted in their seats, eyes quick and cruel, before snapping back to the pulpit. The preacher spoke of mercy, but the weight in the room made the word ring hollow.

She sat stiff, listening not to the sermon, but to the faint breaths of the babies. Each sigh a fragile anchor. And then, unexpected, something broke the hush. A child, no more than five, slid from his mother’s lap and toddled down the aisle. He reached her pew without hesitation, his small hand brushing the cradle cloth to touch the tiny fist of one twin. The baby’s fingers curled, weak but certain, around that hand. For a moment, the judgment cracked and a soft murmur rose—half scandal, half wonder.

She felt her throat tighten, eyes stinging. The boy’s mother hurried forward, pulling him back, but the moment lingered in the air like a bell’s last toll.

When service ended, she waited until most had left before slipping outside. The rancher stayed close, but he did not crowd her. She walked past the murmurs, past the narrowed eyes, her jaw clenched. The air smelled of bread cooling on window sills and horses sweating in the sun. Yet beneath it all lay the sour tang of gossip heavier than any dust.

By the river that edged the town, she finally stopped. The water ran shallow, broken by stones that flashed in the light. She knelt, setting the twins in the grass, and dipped her hands in. The chill made her gasp. She splashed her face, then let the current slide over her wrists, washing the angry marks until they seemed fainter. Her reflection wavered in the water, blurred, unrecognizable.

“They said I wasn’t wanted,” she whispered, not looking at him. “Not by my father. Not by the man who claimed me. Not by the town that tied me there. Not even by the children’s cries when they went silent. I wasn’t enough for anyone.”

The words came halting like stones dragged from the riverbed, heavy with silt. He crouched beside her, his boots pressing into wet soil. He didn’t answer quickly. Words had to be chosen the way nails are driven—careful, deliberate, or else the whole beam splits. At last, he said, “You’re here. That’s enough.” His voice carried no sermon, no polish, just the steady grain of truth.

She turned, meeting his eyes for the first time without flinching. Something in his gaze held her—not possession, not pity, but recognition, as though he had seen that same kind of emptiness once in his own mirror. She felt her chest ache with something like the first breath after near drowning.

The babies stirred, one giving a sharp, healthy cry. She scooped them up, pressing them close, the sound cutting through her like light breaking cloud. He stood, offering his hand. She hesitated, then placed her palm against his. His grip was strong, but not binding. For the first time, her heart did not race in fear.

They walked back together, the river trailing behind them with its endless voice. The town still loomed, the judgment still waiting, but her shoulders no longer bowed so low. She felt the warmth of the twins, the solid presence of the man at her side, and knew she was not as invisible as she had believed.

As the wagon carried them home, dusk draped itself across the sky, staining the horizon in golden rose. The babies slept soundly, their breaths weaving into the rhythm of the wheels. She let her eyes drift toward the man beside her, saw the lines of wear, the silence carved deep into him, and wondered what had broken him before he found her. She almost asked, but his hand shifted slightly on the reins, the leather creaking, and the question died in her throat.

At the edge of his land, where the cottonwoods whispered in the evening breeze, he drew the team to a halt. From his coat, he pulled the folded paper he had carried since the crossroads. He looked at it a long moment before holding it out to her. In the fading light, the inked badge and the words beneath seemed to darken, heavy as stone.

Reward for a young woman with twin infants, wanted for return.

Her breath caught. The twilight wrapped them in silence, and the baby stirred as though sensing the weight of it. She stared at the paper—at proof that the world’s judgment was not finished with her yet—and her grip tightened on the children as though the river might rise again to take them.

He did not let the paper speak the last word. He folded it once more, fed it to the stove’s small fire, and watched ink blacken, then curl to ash. Her shoulders loosened a fraction, then tightened again, as if hope were a door that swung and stuck.

Outside, clouds massed over the cottonwoods. He checked the roof line with his eyes, measuring every weak board, already bracing for a weather the earth had not asked for. He set water to warm and tore rags into clean strips. She bathed the twins with careful hands, as if the river still watched and might withdraw its blessing. Their cries were stronger now, thin cords tuning themselves to the room.

The wind came early, fingering the eaves. A spoon windchime he had fashioned from bent handles rang a timid note, then a braver one. He closed the shutters and laid his coat near the cradle like a vow. By afternoon the sky bruised purple-green. He brought in the barrel, lashed the door, and set a pot to boil. From a tin he had bought on a whim months back, thin noodles slid like straw. He stirred them with a wooden spoon until the water turned cloudy and forgiving.

She watched the steam rise, eyes wary, shoulders squared against the knock she felt coming. The twins slept, open-mouthed, dreaming milk.

The knock found them at dusk. It was not loud. It did not need to be. He wiped his hands, crossed the room, and opened the door to men wearing Sunday anger on weekday faces. The sheriff stood a half step ahead, coat dark with road dust, badge dull as a spent coin. Behind him, two townsmen shifted their weight as if a fight could be shaken free from the porch like mud from a boot.

“Evening,” the sheriff said, the word trimmed of courtesy. “We’ve business—the girl with the infants. We’re returning what ain’t rightly yours.” His gaze slid past the rancher to where she stood by the cradle, the lamp laying a soft circle around her. She did not step back. The windchime rang once as a warning, then fell still.

The rancher put one hand to the doorframe as if feeling the grain for strength. “No,” he said, plain as water. He did not raise his voice. The word filled the room anyway.

The sheriff’s mouth twitched, not quite a smile. “You’ll make it easy,” he said, “or you’ll make it mess.” One townsman smirked. The other studied his boots as if the planks held more law than any badge.

She lifted one twin to her shoulder and stepped forward until the lamplight wrote a line across her cheek. “I won’t go,” she said, and though her voice trembled, it carried.

The sheriff looked past her, surveying the poor room, seeing not a home, but a claim he thought he could erase. He set his boot on the threshold. The wind pushed at his coat as if the night itself had an opinion.

The rancher stepped between them—not a lunge, only placing his body where the law had planted its boot. “She’s under my roof,” he said. “The children, too.” He reached back, palm open, and she set the second twin into his arms. The baby’s breath warmed his wrist—a small furnace of proof. He nodded toward the family Bible on the shelf, the blank leaves kept for names. “Write it down,” he said softly. “Tonight.”

The sheriff barked a laugh. “Ink ain’t marriage. This is return of property.”

The word scraped her like a knife. The rancher did not flinch. “Then return me,” he said. “Take me in her place, and the babies stay.”

The sheriff hesitated. The townsmen traded quick looks. Thunder rolled low, a wagon of iron crossing the sky. The windchime rang again, steadier, as if the spoons had decided which song they’d sing.

From the yard came a small voice. The church boy stood by the fence, a crust of bread in his hand, his mother behind him, pale but steady. The boy pressed his palm to his chest and looked up at the sheriff without a word. The mother lifted her chin. “Mercy keeps better order than chains,” she said. It was not loud, but it carried like a bell.

Neighbors had gathered behind the sheriff, drawn by weather and rumor. The widow from the store stood among them, spectacles glinting with a thought she had not finished. No one stepped forward to help the law.

The rancher shifted the baby higher and felt the small weight settle as if choosing a side. “This house is mine,” he said quietly. “What’s inside it is under its peace.”

The sheriff glanced at the sky, then at the faces that would remember this hour longer than any statute. He spat into the dust, the gesture small and mean, and stepped back from the threshold. “Keep your roof,” he said. “But if she shows in town, she shows to me.” He turned on his heel. The townsmen followed, their bravado already softening under the first cold drops that spotted the yard.

Rain found the roof fast, drumming the tin until the seams sang. He shut the door and held it with his palm, feeling the wood’s thrum—the way a body feels a horse calm after a spook. She slid down the wall, the twin on her shoulder hiccuping into sleep.

“You offered yourself,” she said.

He set the baby in the cradle and nodded like a man accepting weather. He ladled noodles into two bowls and set them on the table. Steam curled up like something forgiven. They ate without hurry, sharing the last heel of bread, the twins breathing softly in their wooden boat.

After, he brought out the family Bible, opened to the clean leaves, and waited. She wrote first—not her history, not the town’s names, only the shape of herself as she chose it now, and the children’s under the roof’s quiet mercy.

Outside, the wind rattled the windows, but inside, a new silence took root—a silence that held, for once, the weight of hope.

You can copy and paste this story into any word processor or website, and it will display in the default basic font.

.

play video: