When the Taliban Punished Women in Public *WARNING Disturbing Historical Content

When the Taliban Punished Women in Public: The Legacy of Fear in Afghanistan

The rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan marked the beginning of a new era of fear, especially for women. Their strict rules and brutal public punishments became a defining feature of Afghan society, leaving scars that persist to this day. The Taliban’s system of control, enforced in full view of the public, not only shaped an entire generation of Afghan women but also continues to haunt the country’s collective memory.

Afghanistan Before the Taliban

Afghanistan in the 1970s was far from perfect, but it offered women opportunities that would later vanish. In cities like Kabul, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif, women attended universities, worked in offices, and moved freely. Kabul University was home to thousands of female students, especially in medicine, literature, and law. Hospitals depended on female nurses and doctors, and women were a common sight in banks and government offices. Girls walked to school carrying books, some wearing headscarves and others not. Families enjoyed weekends in public gardens or lakes, Afghan radio played music, and cinemas screened movies. Bookstores sold novels from across the region. While Afghan society was conservative, urban life had a sense of hope and possibility. Women felt they could dream and grow.

This relative calm was shattered in 1979 when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. The conflict destroyed infrastructure, homes, and entire neighborhoods. Rockets struck cities that had once been peaceful, and many families fled to Pakistan or Iran. The war took the lives of around one million Afghans over ten years and left the country deeply wounded. During this period, local militias formed, each with its own leader and methods. While some tried to help locals, others were violent and predatory.

When the Soviets withdrew in 1989, Afghans hoped for peace. However, the militias began fighting each other for power. From 1992 to 1994, Kabul became extremely dangerous, with rockets landing on markets, buses, and homes almost daily. Women’s freedom slowly shrank as violence increased. Exhausted by endless battles, people longed for stability, order, and someone who could stop the chaos.

.

.

The Rise of the Taliban

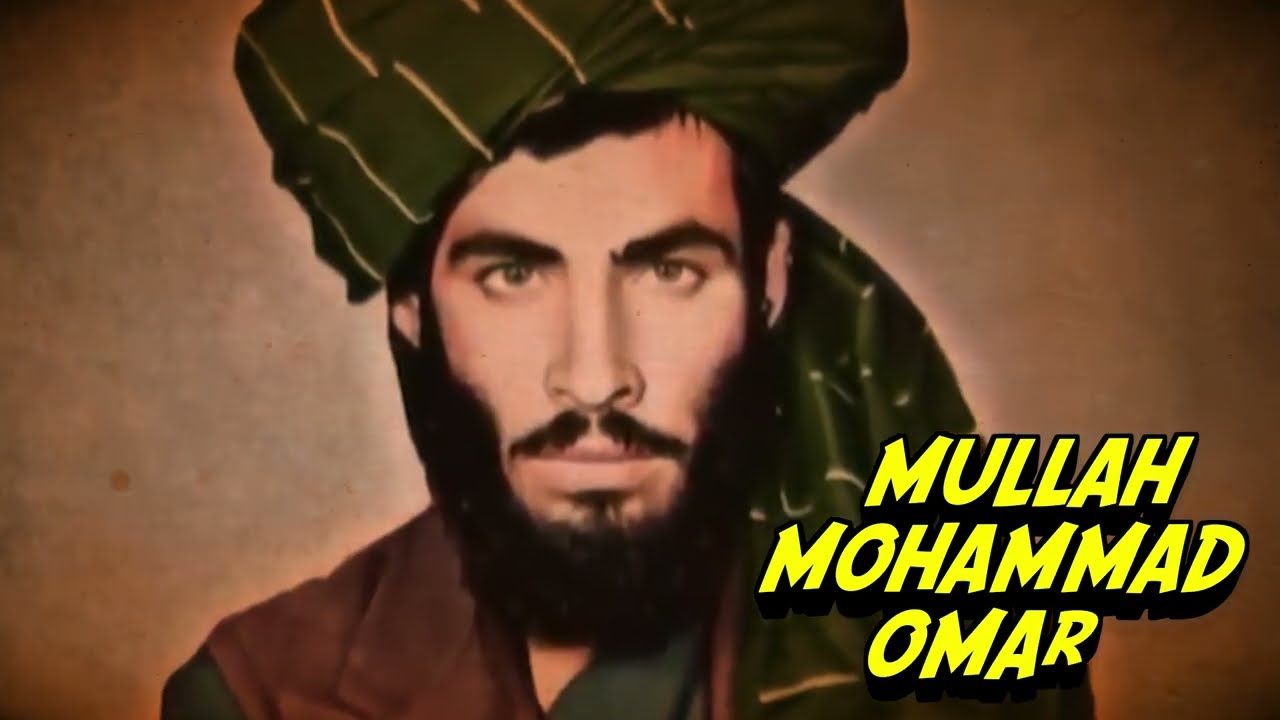

In this atmosphere of desperation, the Taliban emerged. They promised to end corruption and restore order. The group first appeared in 1994 near Kandahar, led by Mullah Mohammad Omar, a former fighter who lost an eye during the Soviet war. Many early Taliban members were young men raised in refugee camps and educated in religious schools, where studies focused almost entirely on religious texts. They were strict, disciplined, and determined to impose their version of Islamic law.

Southern Afghans, fed up with theft, kidnappings, and militia corruption, initially welcomed the Taliban. When the group punished local criminals in 1994, villagers saw them as a solution. Support spread quickly, and within a year, the Taliban controlled much of Kandahar province. By early 1995, they advanced north and east, capturing Ghazni, Zabul, and parts of Helmand with little resistance. Warlord groups were weakened and unpopular. The Taliban replaced local courts with their own judges and, by mid-1996, controlled large areas in the south and west.

The turning point came in September 1996, when the Taliban entered Kabul after two days of fighting. Government leaders fled, and the Taliban announced the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Life changed overnight. Women were banned from working in offices, hospitals, and schools. Girls’ schools closed within weeks, and strict clothing rules were imposed. Leaving home without a male relative became dangerous. Music, movies, and other forms of entertainment disappeared. At first, these rules were warnings, but as the Taliban consolidated power, they enforced them publicly and brutally.

Public Punishments: A System of Fear

The Taliban chose public places like Ghazi Stadium and later the larger Kabul Sports Stadium to carry out punishments. Thousands were forced to witness these events, reinforcing the regime’s control through fear. Women accused of violating Taliban rules—walking outside without a male guardian, wearing shoes deemed too loud, or attempting to return to work—were brought before crowds. Punishments were swift and severe, often involving lashes administered with sticks, cables, or whips. The number of lashes depended on the accusation, sometimes ten, sometimes more than thirty. Kabul residents had never seen such public brutality.

The impact was immediate and devastating. Women who once moved confidently now stayed home for days. Families feared letting daughters leave the house, even for basic needs. Hospitals struggled as experienced female workers were removed. The Taliban realized that public fear was an effective tool of control, and they tightened their grip, creating an increasingly severe system.

By 1997, Taliban control extended across most of Afghanistan. Cities like Herat, Farah, Nimruz, Uruzgan, and Helmand fell under their rule. Each city was placed under the authority of a Taliban commander, who enforced rules with varying degrees of severity. Herat became one of the harshest places for women, with Mullah Abdul Manan Niazi imposing some of the most severe restrictions. Nurses and female hospital workers were beaten for working without permission. In Kabul, accusations and punishments became routine. Women were punished for wearing socks deemed too thin or walking “too boldly.” Many sought medical treatment secretly at night, fearing punishment for both themselves and the doctors who helped them.

The Taliban’s Department for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice patrolled markets and streets, questioning women about their behavior. Fear spread so deeply that families covered windows with heavy curtains, and daughters avoided sunlight. Normal life disappeared.

The Expansion of Brutality

In 1998, the Taliban captured Mazar-i-Sharif, a major city. The battle was bloody, and the aftermath saw women removed from their jobs as professors, lawyers, and government employees. Girls’ schools shut overnight, and house searches targeted women found outside, even near their own doors. Public squares became sites of regular punishment, and markets were places of fear.

Stadium punishments in Kabul grew in scale, with thousands forced to attend. One case involved a woman accused of adultery, punished so severely that even some Taliban supporters were disturbed. But discomfort changed nothing; the system remained.

Herat saw women punished for sewing “unacceptable” clothes or studying in secret groups. By 1999, the Taliban controlled almost the entire country, except for a few northern areas. Their rule became even stricter, with warnings replaced by immediate enforcement. Jalalabad enforced particularly harsh dress codes, and the Department for the Promotion of Virtue grew more aggressive, entering homes without notice and targeting women who represented the “old ways.”

The Turn of the Millennium: Drought and Desperation

By 2000, Afghanistan faced a severe drought. Over three million people struggled to find food. Women, already excluded from public life, suffered most. With no income and restricted movement, even basic survival became risky. Some tried to take on small jobs or sell homemade goods, but Taliban patrols cracked down harder during the crisis. Women caught outside without permission were punished on the spot, even if only trying to feed their children.

In Kandahar, women working as tailors from home were punished. In Herat, secret literacy lessons ended in public beatings. In Kabul, a former doctor was punished for treating a sick child without permission. Internal disagreements emerged within the Taliban, but hardliners prevailed, pushing for stricter discipline.

Collapse and Aftermath

September 2001 brought the attacks in the United States, shifting global focus to Afghanistan. International pressure mounted, and military operations began. By November, the Taliban lost control of major cities. Their system, built over five harsh years, collapsed in weeks. In the chaos, records were destroyed, and many punishments went undocumented. Survivors described a final round of public punishments before the Taliban fled. Women trying to escape were beaten in public squares.

With the Taliban’s fall, women stepped outside without permission for the first time in years. Girls returned to classrooms, and female workers rejoined hospitals, universities, and government offices. From 2002 to 2020, Afghanistan experienced two realities: urban progress and rural conflict. In cities, life improved, but in rural areas, the Taliban slowly returned, establishing shadow courts and reimposing strict rules. Women continued to suffer, with incidents of punishment reported throughout the 2010s.

The Return of the Taliban

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban retook Kabul, and the government collapsed. The progress of the previous twenty years vanished almost instantly. Women were told to stay home, girls’ high schools closed, and female workers were dismissed. The Taliban promised things would be different, but within weeks, patrols questioned women and enforced strict dress codes. Public punishments resumed quietly at first, then more openly. In December 2021, women in Ghor province were punished for “moral crimes,” often vague accusations with no chance for defense. Families who tried to help were warned to stay silent.

By early 2022, punishments were carried out in mosques and public spaces. The Taliban’s supreme leader ordered traditional punishments to be fully enforced again, and cases spread fast. Public punishments, including lashes, were carried out in front of crowds, including children. The most shocking event occurred in December 2022 in Farah province, where over 1,000 people witnessed men and women punished in a stadium.

The System of Control

By 2023, Afghanistan had become one of the most restrictive countries for women. Public punishments continued in provinces like Bamyan, Kandahar, Nuristan, and Badghis. Women who once studied engineering, journalism, medicine, or law now stayed home, their futures uncertain. The Taliban’s system of punishment follows a strict structure: the Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue, district commanders, religious judges, and local enforcers. Cases are reported, judged quickly, and women have no lawyers or defense. Families remain silent out of fear.

This system, barely changed from the 1990s to the 2020s, continues to shape every part of women’s lives. The world watches, realizing that for Afghan women, the darkest chapters are not history—they are lived reality.