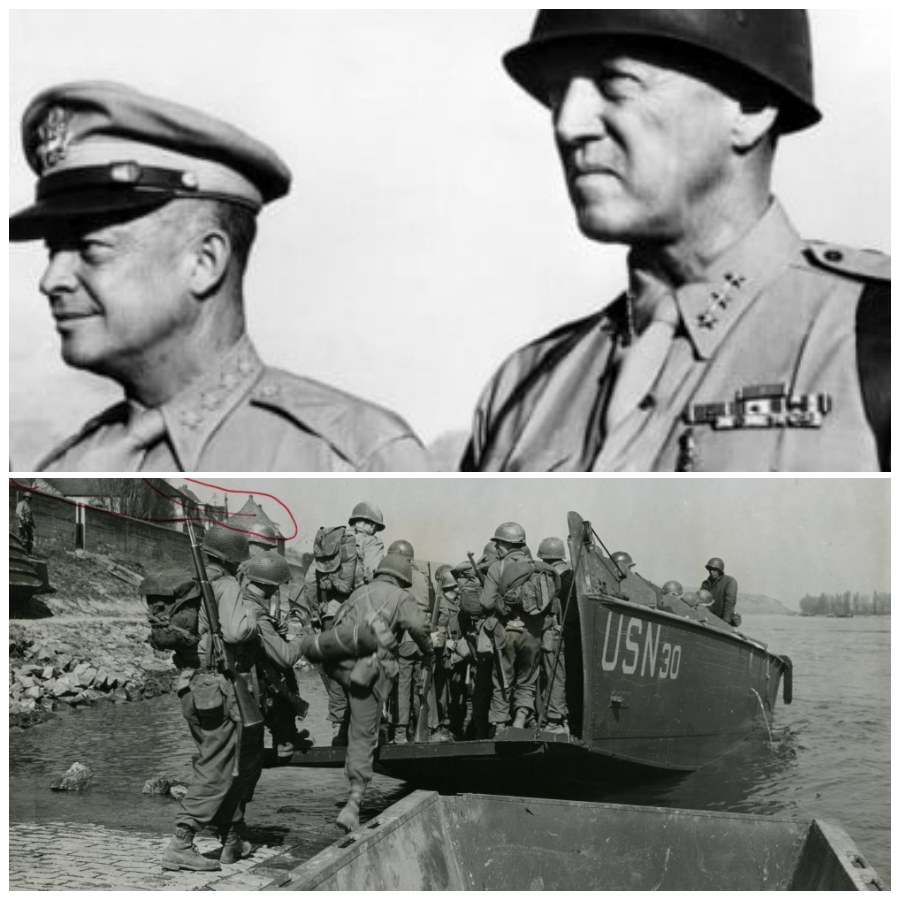

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Stole Montgomery’s Glory at the Rhine

March 22nd, 1945. The Rine River. One word echoed through every Allied command post from Paris to the front lines. Impossible. The Rine was Hitler’s last natural barrier. Military engineers had calculated it would take weeks to build pontoon bridges under enemy fire. British Field Marshall Montgomery was methodically planning a massive setpiece crossing with thousands of troops, artillery barges, and airborne drops.

Even American commanders estimated any crossing would require extensive preparation, air superiority, and overwhelming force. George S. Patton had other ideas. At 1000 p.m. the night before, he’d called Eisenhower with news that seemed too audacious to be real. His lead elements had already crossed the Rine.

Not next week, not with elaborate preparations that night. Using assault boats and sheer aggression, Patton’s third army had forced a crossing at Oenheim before the Germans even knew what was happening. When Eisenhower hung up that phone, when he stood alone in his office processing what Patton had just accomplished, he whispered something to himself that revealed everything about genius, rivalry, and the burden of commanding men who refuse to accept limitations.

This is the story of that crossing, those whispered words, and what happens when impossible becomes inevitable. If this untold story has already grabbed you, hit that subscribe button now. We’re diving into the private moments that shaped history, the whispered truths that textbooks ignore, and the human drama behind legendary decisions.

Drop a comment telling me what fascinates you most about World War II leadership. Now, let’s get back to March 1945 when everything was about to change. March 1945, the Allied armies had pushed German forces back across the Rine, but now they faced the most formidable obstacle in Western Europe.

March 23rd. It would be the most elaborately planned river crossing of the war.

Thousands of artillery pieces, massive aerial bombardment, airborne drops behind enemy lines. It was methodical, overwhelming, and very British. Patton hated it. Not because it wouldn’t work. Montgomery’s plan would almost certainly succeed. Patton hated it because it was slow. While Montgomery prepared his set peace operation, Patton saw opportunity slipping away.

German forces were reeling, disorganized, desperate. Every day of preparation gave them time to strengthen defenses. On March 21st, Patton’s forces captured the town of Oppenheim, a small river crossing south of Mines. And Patton noticed something that would change everything. The German defenses at Oppenheim were weak, undermanned.

The Vermacht had concentrated forces to defend against Montgomery’s obvious preparations further north. They’d left this section of the river virtually unguarded. Patton immediately saw what others might have missed. This wasn’t just a gap in German defenses. This was an opportunity to cross the Rine before Montgomery with minimal casualties and without the massive preparation everyone assumed was necessary.

But there was a problem. Eisenhower hadn’t authorized any crossing at Oppenheim. The plan was for Patton to support Montgomery’s operation, not launch his own. Crossing without authorization would be classic Patton. Brilliant, insubordinate, and potentially disastrous if it failed. What happened next reveals everything about Patton’s command philosophy and his complicated relationship with Eisenhower.

March 22nd, 1945, 10 p.m. Major General Manton Eddie, commanding 12th Corps, received a call from Patton himself. The conversation was brief and characteristically aggressive. Manton, how fast can you get boats across the Rine at Oppenheim? Eddie, who knew his commander well, understood immediately what Patton was asking.

Tonight, if we move now, then move now. I want a battalion across before midnight. I want a bridge head established by dawn. and Manton. Don’t ask for permission, just do it. At 10:30 p.m., assault boats carrying men from the fifth infantry division slipped into the Ry River. No artillery preparation, no air support, no elaborate planning, just infantry in boats crossing in darkness, hoping the German defenses were as weak as reconnaissance suggested.

They were. By midnight, American forces had established a foothold on the eastern bank. By 2:00 a.m. they’d expanded the bridge head. By dawn on March 23rd, engineers were already building pontoon bridges and tanks were preparing to cross. Patton had forced a crossing of the Rine before Montgomery with minimal casualties using speed and audacity instead of overwhelming force.

Now he just had to tell Eisenhower. March 23rd, 1945, 10:00 a.m. Eisenhower was at his headquarters in Reigns, reviewing plans for Montgomery’s crossing scheduled forlater that day when his phone rang. His aid announced General Patton calling from Luxembourg. Eisenhower picked up, expecting a routine update on Third Army’s positioning.

What he heard instead was pure patent. Good morning, Ike. I want to report that we crossed the Rine last night at Oppenheim. We’re expanding the bridge head now. Tanks should be across by this afternoon. Minimal casualties. Germans were completely surprised. Complete silence on Eisenhower’s end. Patton recognizing that silence continued.

Ike, I know this wasn’t in the plan, but the opportunity was there. Weak defenses, minimal risk, maximum reward. We’re across the Rine with a fraction of the casualties Montgomery’s operation will cost. Still silence. Then Eisenhower spoke, and witnesses in his office later said his voice was carefully controlled, revealing nothing. George, you crossed the rine without authorization.

Yes, sir. Last night, it was the right decision. The right decision would have been informing your superior officer before launching a major operation. If I had asked permission, you would have said to wait, and if we’d waited, the opportunity would have disappeared. This was the essential tension in their relationship crystallized in one conversation.

Patton was operationally brilliant but institutionally impossible. Eisenhower was right to be frustrated. Patton was also right that the crossing had worked perfectly. After what felt like an eternity, Eisenhower responded, “George, expand your bridge head. Get your armor across. Exploit success.” A pause.

And for God’s sake, don’t do this to me again. “Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.” After hanging up, Eisenhower sat motionless for several moments. His chief of staff, General Walter Bettles Smith, was in the office. He later recorded what happened next in his diary. Eisenhower stood, walked to the window, looked out at nothing in particular, and said quietly, “Bedell, George just crossed the Rine before Montgomery, without authorization, without preparation, with minimal casualties, and I can’t even be properly angry because it worked perfectly.”

Smith asked what Eisenhower planned to do. do nothing. George just handed us a bridge head across the Rine. What am I supposed to do? Order him back across the river to maintain proper protocol? Then Eisenhower said something that Smith underlined in his diary entry that night. This is George’s genius.

He sees opportunities others miss and acts before those opportunities disappear. He’s also maddeningly insubordinate. Those two things cannot be separated. I get both or I get neither. What most histories miss is what happened in Eisenhower’s office over the next hour. What he said to Smith, what he wrote in private notes, what he whispered to himself when he thought no one was listening.

Smith’s diary provides the only detailed record. After the initial conversation, he asked Smith to stay. They were alone. Eisenhower sat heavily in his chair, suddenly looking exhausted despite the successful news. Bedell, I need you to understand something. I’m furious with George right now. Not because the crossing failed. It succeeded brilliantly.

I’m furious because he put me in an impossible position. Smith asked what position that was. If the crossing had failed, if we’d lost men trying to force the rine without preparation, I would have had to relieve George from command. Court marshall, possibly end of career, certainly. But it succeeded. So now I have to praise operational brilliance while ignoring flagrant insubordination.

Eisenhower continued choosing his words carefully. George gambled with his career with American lives with our operational plans. And he won. The bridge head is secure. Casualties are minimal. were across Hitler’s last barrier ahead of schedule. By every operational measure, this is a triumph. But but George made this decision unilaterally without authorization, without even informing me until after it was done.

That’s not how military command works. That’s not how coalitions function. If every general operated like George, we’d have chaos. Then Eisenhower said something that reveals the true burden of his command. Smith recorded it word for word. The problem with George is that he’s proven his methods work. Baston proved it. Sicily proved it.

And now the rine proves it. He sees opportunities that more cautious commanders miss. He acts when others would hesitate and he wins. Smith noted that this was a good problem to have. Eisenhower’s response was bitter. Is it? Because right now I can’t discipline the most insubordinate general under my command because he’s also one of the most successful.

What message does that send to other commanders? Follow orders unless you think you know better. Obey the chain of command unless insubordination might work out. Eisenhower stood and walked to his desk. He pulled out a piece of paper and began writing. Smith watched silently. After a few minutes, Eisenhower lookedup. I’m drafting two messages.

One is a formal commendation for Third Army’s successful crossing of the Rine. Operational excellence, minimal casualties, strategic achievement. All true, all deserved. and the other a private message to George reminding him that success does not excuse insubordination, that he serves at my pleasure, that if he ever launches an unauthorized operation again, I will relieve him regardless of the outcome.

” Smith asked if Eisenhower actually planned to send both messages. Eisenhower’s answer was revealing. I’ll send the commenation immediately. The reprimand I’ll hold. Let George enjoy his victory for a day. He earned it, even if he earned it by ignoring every principle of military command. Then Eisenhower whispered something that Smith almost didn’t hear.

Smith wrote that he had to ask Eisenhower to repeat it. I said, “Thank God for difficult men who win battles because that’s what George is. Difficult, brilliant, impossible to manage and absolutely essential.” That afternoon, Eisenhower issued a statement to all Allied forces. Units of Lieutenant General George S.

Patton’s third army have successfully established a bridge head across the Rin River at Oppenheim. This rapid exploitation of enemy weakness demonstrates the aggressive spirit and operational excellence of American forces. No mention that the crossing was unauthorized, no mention of the risk Patton had taken, just public praise for a successful operation.

But in his private correspondence, Eisenhower was more honest. To General Marshall in Washington, he wrote, “Patton crossed the Rine last night without authorization. The operation succeeded brilliantly. I am simultaneously impressed and infuriated. George’s operational instincts are superb.

His respect for command authority is non-existent. I cannot praise him publicly while disciplining him privately without looking hypocritical. This is the impossible position George constantly puts me in to Montgomery who would launch his own massive crossing later that day. Eisenhower wrote diplomatically, “Third Army has established a bridge head at Oppenheim.

Your operation remains the primary effort. Patton’s crossing, while successful, does not diminish the importance of Operation Plunder. This was crucial. Montgomery was sensitive about American operations overshadowing his carefully planned efforts. Eisenhower had to manage Montgomery’s ego while praising Patton’s achievement.

But to Patton himself, Eisenhower sent a private telegram. George, congratulations on successful crossing. Bridge head secured. Casualties minimal strategic gain significant. However, future operations will be coordinated with this headquarters before execution. Your operational judgment is valued. Your disregard for command authority is not clear.

Patent’s response was characteristically brief. Crystal clear, Ike. Thanks for the confidence. We won’t let you down. Whether Patton actually learned anything from this exchange is debatable. What’s clear is that Eisenhower had found a way to manage the contradiction. Praise publicly, reprimand privately, and accept that Patton would always operate at the edge of acceptable behavior.

The Ry Crossing crystallized everything about Eisenhower’s command of Patton. In his personal diary that night, Eisenhower wrote his most honest assessment. George Patton crossed the Rine today without permission and succeeded brilliantly. This is George in a sentence. Brilliant, insubordinate, impossible, essential.

I cannot fire a general who wins battles. I cannot fully trust a general who ignores orders. So I manage the contradiction and hope that George’s brilliance outweighs his insubordination more often than not. What Eisenhower whispered in his office, what he confided to Smith, what he wrote in private letters all pointed to the same conclusion.

Patton was ungovernable, [music] irreplaceable, and absolutely necessary. The whispered truth was simple but profound. Thank God for difficult men who win battles. This wasn’t resignation. It was recognition. Eisenhower understood that Patton’s genius and his insubordination were inseparable. The same aggressive instinct that led Patton to cross the rine without permission was the same instinct that made him see opportunities others missed.

You couldn’t have one without the other. Years after the war, in his memoir, Eisenhower devoted an entire chapter to Patton. He wrote, “George Patton was the most gifted battlefield commander and the most difficult subordinate I ever commanded. He saw opportunities where others saw obstacles. He acted when others hesitated, and he won when others would have accepted stalemate.

” Managing George required patience, flexibility, and a willingness to accept that brilliance often comes with complications. But it was in a private letter in 1963, 2 years before his death, that Eisenhower was most revealing. Writing to a military historian, he reflected, “People ask me if I wouldhave kept Patton in command if I could do it again.” Yes, without hesitation.

George frustrated me constantly. But when I needed someone to do the impossible, George delivered. The rin crossing proved that. He saw an opportunity, acted immediately, and succeeded. Was he insubordinate? Absolutely. Was he right? Also, absolutely. That’s the burden of command. Managing people who refused to accept limitations.

What did Eisenhower whisper when Patton forced a breakthrough no one expected? He whispered gratitude for difficult men who deliver results. He whispered frustration at insubordination that works. He whispered recognition that genius cannot be managed by conventional rules. He whispered the essential truth of leadership.

Sometimes you don’t choose between the difficult and the effective. Sometimes they’re the same person and your job isn’t to change them, but to channel them. Patton’s unauthorized rine crossing wasn’t just a tactical victory. It was a defining moment in their relationship. It proved that Patton would always push boundaries, always take risks, always ignore protocol when he saw opportunity.

And it proved that Eisenhower would tolerate this because the results justified the frustration. The whispered words weren’t about tactics or strategy. They were about accepting that the best commanders are rarely the easiest to manage. that innovation requires insubordination, that winning sometimes means tolerating behavior you’d never accept in others.

Eisenhower’s whispers revealed the leader who understood the paradox of command. The people who deliver miracles are often the same people who cause the most problems.