A Bigfoot Begged a Man for Help in Perfect English. What Happened Next Will Shock You!

The Night Walker Knocked

.

.

.

When I heard the words, “Please, I need your help,” spoken in clear, articulate English from outside my cabin door, my first thought was that a lost hiker needed assistance. But when I opened the door and saw what was standing on my porch—a seven-and-a-half-foot Bigfoot covered in dark brown fur, with hands that looked almost human and eyes that held unmistakable intelligence—I realized that everything I thought I understood about the world had just become irrelevant.

My name is Glenn Rivera. I’m sixty-five years old, and I’ve lived in this isolated cabin in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southern Washington State for the past twelve years, ever since I retired from teaching high school biology in Portland. My wife passed away in 1982, and after thirty years of classroom noise and city traffic, I wanted silence, space—the kind of solitude you can only find forty miles from the nearest town, on a dirt road that’s impassable half the year.

It’s November 1995. Bill Clinton is president. The OJ Simpson trial dominated the news earlier this year. The internet is a novelty, accessed through screeching dial-up modems. I don’t have a computer or a cell phone. I have a landline that works when the weather cooperates, a 1988 Ford Bronco, and a shortwave radio for emergencies. My cabin sits on eighty acres of forest I bought with my retirement savings. The nearest neighbor is eight miles away—a hunting lodge only occupied during deer season.

My days are quiet. I read, maintain the property, and occasionally drive to the small town of Trout Lake for supplies. I’ve seen elk, black bears, cougars, and once a wolverine. I’ve heard strange sounds at night—vocalizations I couldn’t identify, which I always assumed were owls or coyotes. Twice, I found footprints near my creek that were too large to be bear and the wrong shape for any animal I knew. I dismissed them, convinced they were hoaxes or misidentified bear tracks. I never believed in Bigfoot.

Even when students brought up the Patterson-Gimlin film in my biology classes, I steered them toward scientific thinking. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Absence of bodies, lack of DNA, the statistical impossibility of a breeding population going undetected—I was wrong. Catastrophically, fundamentally wrong.

The evening of November 14th, 1995, started normally. I spent the day splitting firewood, made dinner, listened to the radio, read a biography of Darwin. Around 10:45 p.m., I was getting ready for bed when I heard footsteps—heavy, deliberate—coming up the path to my cabin. I grabbed my flashlight and Winchester rifle, just in case.

“Who’s there?” I called out.

Silence, then, “Please, I need your help.” The voice was male, deep, perfectly articulated English, spoken with desperation.

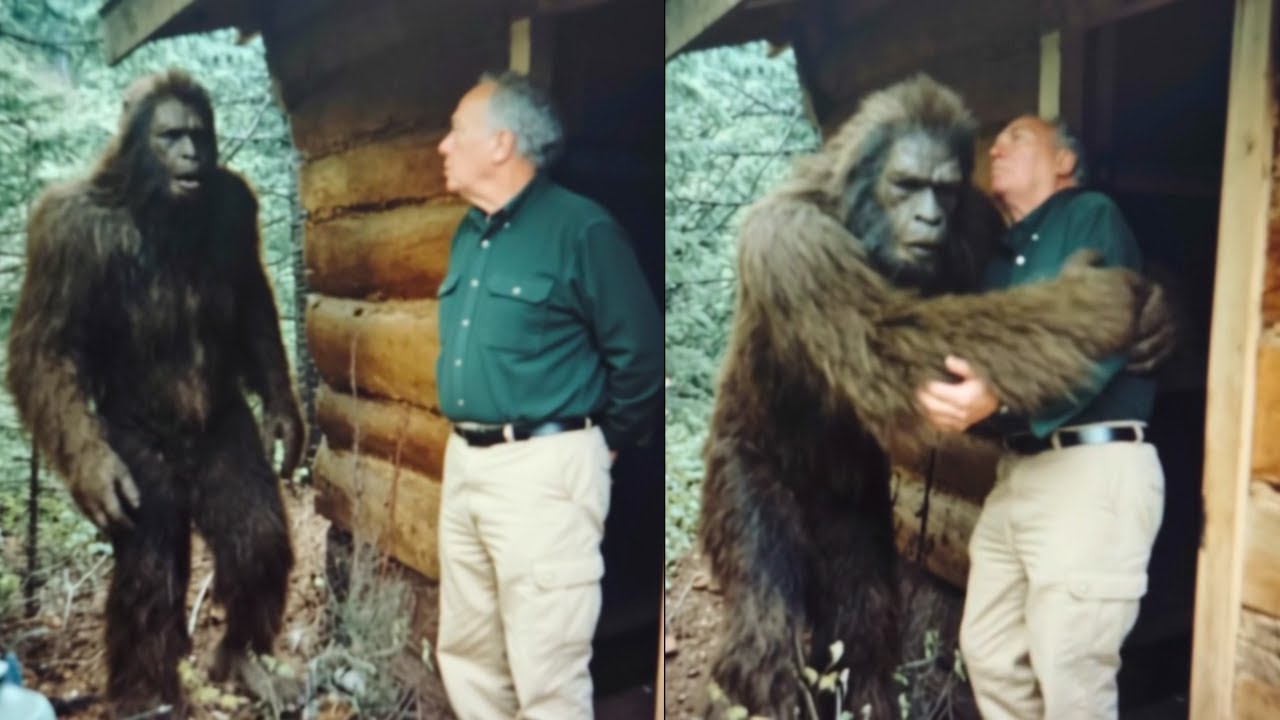

I unlatched the door and opened it, rifle held low but ready. My flashlight illuminated something that shouldn’t exist—seven and a half feet tall, covered in thick, dark brown fur, matted with pine needles and dried mud. Massively built, upright, humanlike posture. The face was what stopped my breath—not quite human, not quite ape, something in between. But the eyes—dark brown, deeply set—held awareness, understanding, and fear.

The creature raised its hands in a universal gesture of non-threat. “Please don’t shoot. I’m not here to hurt you. I need help.”

I stood frozen, trying to process what I was seeing and hearing. This violated everything—biology, zoology, linguistics, probability.

“You’re… you’re speaking English,” I managed.

“Yes. I learned by listening over many years. Please, I don’t have much time to explain. Something happened. I need help. Human help.”

The urgency was clear, but so was exhaustion. “What are you?” I asked.

“I don’t have a word for what I am in your language. You call my kind Sasquatch, Bigfoot, but those are your words, not mine. My name, the closest translation, would be Walker. I’ve lived in these mountains for seventy-three years.”

Walker was older than I was, had learned English by listening to humans from a distance, and now stood on my porch asking for help.

“Why me?”

“Because you live alone. Because I watched your cabin for three years—you never hunt, never harm the forest unnecessarily. Because you’re old enough to maybe, maybe listen instead of react with violence. Because what I need help with, I cannot do alone.”

Walker stepped closer, and I saw the injury—his left leg had a significant wound just above the knee, a gash six inches long, caused by something sharp. Not recent, maybe three or four days old.

“Three days ago, I was exploring a cave system I’d never entered before, fourteen miles northeast in the high country. I was careless, fell through a weak section of floor into a lower chamber. The fall damaged my leg, struck rock on the way down. But that’s not why I’m here. When I fell, I found something. Something humans need to know about. Something dangerous.”

“What kind of something?”

“Containers. Metal containers. Dozens, stacked in the deep chamber. They have symbols—warnings in your language. Radiation symbols. Hazard markings. They’re old, rusting. Some are leaking.”

My stomach dropped. “You’re saying there are radioactive materials stored in a cave in the national forest?”

“I don’t fully understand what radioactive means, but I’ve seen these symbols before, long ago when humans were doing something in these mountains. I’ve seen what happens to animals near these containers—they sicken, their fur falls out, they waste away. This is poison. Human poison, hidden in a place where no human would normally look.”

“Why not just report it?”

“Because I’m not supposed to exist. If I revealed myself to report this, I become the discovery. I become captured, studied, confined. No one pays attention to the poison because they’re too interested in me. But you, you can report it. Say you found it while hiking. No one questions a human finding something in the forest.”

He was right. If a Bigfoot revealed itself to report environmental contamination, the creature would overshadow the actual problem.

“Even if I believe you, why should I risk my credibility to report something I didn’t actually find?”

“Because if you don’t, that poison keeps leaking into groundwater, into the forest, into the animals, eventually into the humans who drink from the streams that start in these mountains. And because I’m asking one living being to another—please.”

His posture and tone suggested desperate honesty. “You can’t access the cave because of your leg?”

“Correct. The entrance is a vertical shaft. I can’t climb with this injury. And even if I could, I can’t mark the location in a way that would mean something to humans. I don’t know your coordinates, your map systems. But you could. You have knowledge I don’t.”

“You’re asking me to hike fourteen miles into rough terrain, find this cave, verify these containers exist, and then figure out how to report them without explaining how I knew where to look.”

“Yes. I know it’s dangerous. I know it asks too much. But I’ve watched humans for seven decades. If I could solve this myself, I would. But I can’t.”

I lowered the rifle and leaned it inside the door. “Come inside. Let me look at that leg.”

Walker hesitated. “I’ve never been inside a human structure.”

“You’re speaking English and asking for help with environmental contamination. Might as well add entering a cabin to your list of firsts.”

He ducked his head and stepped inside, hunching to fit under my seven-foot ceiling. I examined the wound. It was deep but clean, healing quickly. His immune system must have been remarkable.

“We heal quickly,” he said. “But this was deep enough that it’s taking longer than usual.”

“We?” I asked.

“I meant ‘we’ as in my kind. But I’m the only one in these mountains. The only one I know of anywhere. I’ve been alone for a very long time.”

I finished bandaging his leg. “All right, let’s discuss this cave situation.”

He described the route in detail—landmarks, terrain, the cave entrance concealed by deadfall. I sketched a map as he spoke.

“If you help me, your life changes. You’ll know I exist. You can never prove it to anyone without endangering me. Are you willing to accept that burden?”

I looked at this being who’d learned my language, lived alone for decades, asking for help not for himself but for the forest and people downstream. I made a decision.

“Yes, I’ll help you. But after we deal with the cave, you’re answering questions. A lot of questions.”

Walker’s expression shifted to relief. “Agreed. Now, let me describe the route to the cave. And Mr. Rivera, thank you for listening, for not shooting, for treating an impossible thing as if it deserves basic kindness.”

“Call me Glenn,” I said. “And you’re welcome. Though I reserve the right to decide I’ve had a psychotic break once this is all over.”

Walker made a sound that might have been laughter. “Fair enough.”

And so, at sixty-five years old, sitting in my cabin with a creature that shouldn’t exist, I began planning an expedition to find radioactive contamination in a cave fourteen miles into the wilderness. Just an ordinary Tuesday night in November 1995.

The next two hours were spent at my kitchen table, Walker describing the route, me sketching a map. His navigation was perfect, and his knowledge of the terrain intimate. I realized this was no casual day hike—it would require overnight gear and careful planning.

Walker described the containers—metal drums, three feet tall, marked with radiation symbols and “U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.” He’d seen what they did to animals. I told him I’d need radiation detection equipment and had a friend who could lend me a Geiger counter.

“Tom won’t know about you,” I said. “I’ll tell him I found something concerning while hiking.”

Walker nodded. “You’re already creating the lies you’ll need to maintain the layers of deception required to hide my existence while addressing the problem I brought to you.”

We talked late into the night. Walker told me about his life—born in Canada, his mother taught him to hide, avoid humans, survive by remaining invisible. He’d been alone since 1962, learned English by listening to hikers, rangers, and radios. He was the last of his kind in these mountains.

Around 2 a.m., I insisted he stay—he couldn’t hike back on his leg. He hesitated, but I convinced him. “Tonight seems to be a night of firsts,” I said. “I want to see if a Bigfoot snores.”

Walker settled onto my bed, and I took the couch. As I lay in the dark, I tried to process the magnitude of what had happened. A creature from folklore had knocked on my door, spoken perfect English, asked for help, and was now sleeping in my bedroom.

At dawn, Walker made coffee. We sat at the table, drinking in companionable silence. I told him I’d need two days to prepare for the journey. He said he’d return to his shelters, but would come back after the crisis was resolved.

“When you report what you find, they’ll ask questions,” Walker warned. “You’ll need a convincing story.”

I told him my cover—exploring for fishing spots, noticed a rock formation, saw disturbed ground, found the cave. Simple, plausible, no mention of mysterious informants.

“Call me Glenn. You’re the most interesting conversation I’ve had in twelve years,” I admitted.

Walker nodded. “After things have settled, I’ll return. We’ll talk more. You’ve earned that much.”

He left, vanishing into the forest. I had two days to prepare for the most important expedition of my retirement.

I borrowed the Geiger counter from Tom, gathered supplies, and set out following Walker’s directions. The journey was arduous, but every landmark matched his description. I found the cave, rappelled down, and discovered the drums—fifty-three containers, leaking radiation, marked with military warnings. I measured levels—dangerously high. I photographed everything, documented the site, and left quickly, passing sick raccoons on the way out.

Back at my cabin, I developed the film, organized the evidence, and called the EPA. The response was immediate—field investigators, hazmat teams, federal agents. The forest was swarmed. The contamination was real, significant, and was being cleaned up.

Walker’s territory was shattered by the cleanup. He visited me once, worried about his future. I assured him the cost was worth it—the forest was saved, the contamination stopped. He told me of two other sites, and I promised to investigate.

When the cleanup ended, the forest grew quiet again. Walker returned, thinner but relieved. We talked about friendship, purpose, and the burden of knowing something impossible. He asked if we could continue meeting, just once a month, so he wouldn’t be completely alone.

I agreed. Walker had given my retirement purpose, and I’d given him connection after decades of solitude.

It’s been months now. The forest is healing. The monitoring station operates quietly. Once a month, an impossible friend visits my cabin. We drink coffee, talk, and remind each other that existence is less about what’s possible and more about what’s meaningful.

And that’s enough. More than enough. That’s everything.