“A Park Ranger Took a Baby Bigfoot Home—But When Midnight Came, His Family Faced a Terrifying Regret in This Unforgettable Sasquatch Story”

The Midnight Visitor

.

.

.

When I found the infant creature crying beside the creek at dawn, covered in mud and clearly abandoned, my first instinct was to help. It was a decision that felt compassionate in the gentle morning sunlight—one I would later realize set in motion a chain of events that would turn our peaceful life into absolute terror.

Twelve hours later, something massive began circling our house at midnight, making sounds I’d never heard in forty-three years of working these mountains. Sounds that made my wife, Dorothy, grab my arm and whisper, “What did you bring into our home?”

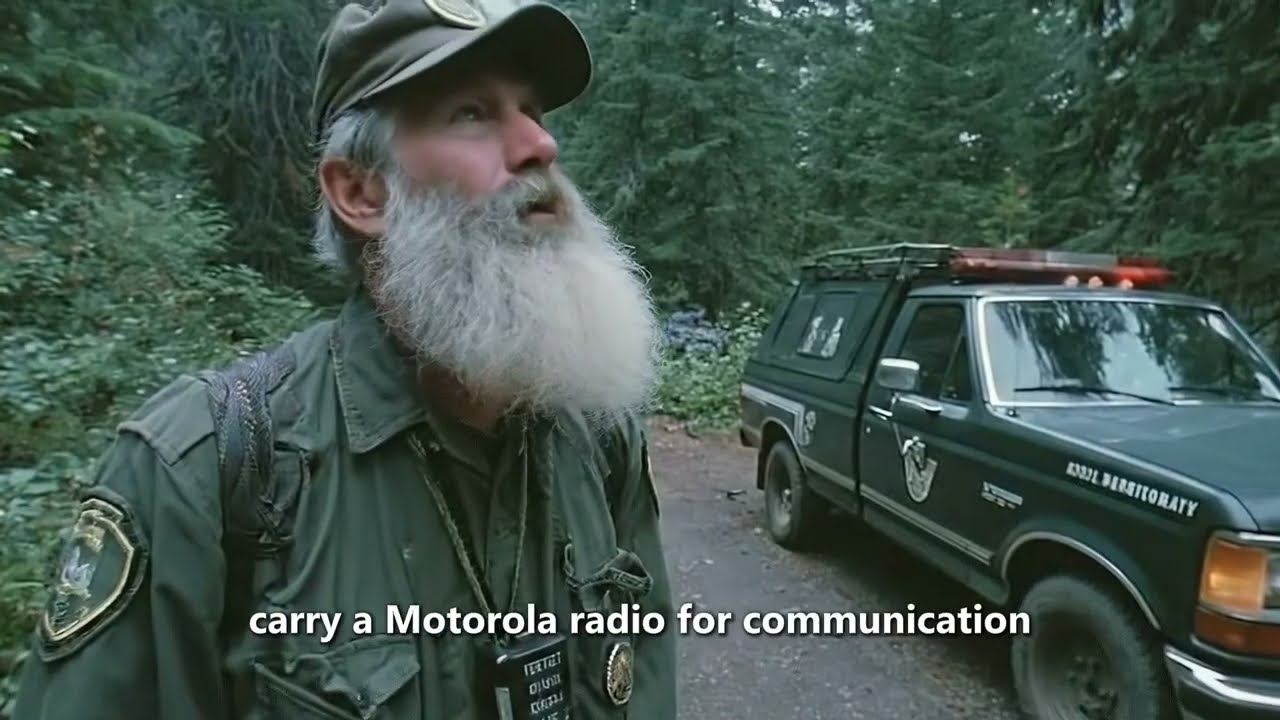

My name is Otis Barnes, and I’m sixty-six years old. I’ve been a park ranger at Mount Rainier National Park in Washington State for the past forty-three years, ever since I was twenty-three and fresh out of the Army. My life has been these mountains—enforcing regulations, conducting search and rescue, monitoring wildlife, and educating visitors. Dorothy and I live in government housing within the park, a modest two-bedroom cabin. Our two children are grown and gone, living their own lives in Seattle and Tacoma.

It was September 1995. The world was busy with its own troubles, but here, life was simple and peaceful. I was eligible to retire, but I kept working because I loved the job and the land. Our days were routine—patrols, gardening, volunteering, quiet evenings with cards and radio.

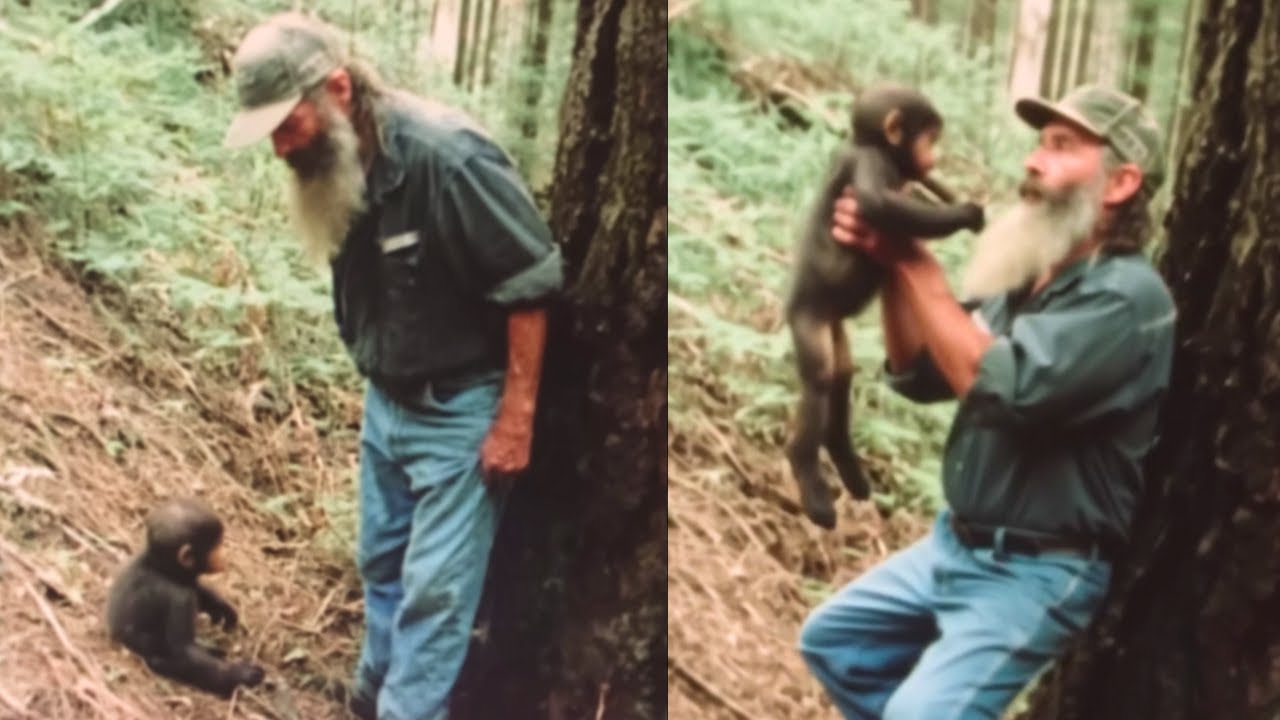

On the morning of September 12th, I was patrolling the Nisqually River drainage. Early autumn, mist in the valleys, the park shifting from summer crowds to the quieter fall. Near Cougar Creek, I heard a sound—something not quite human, not quite animal. A cry, young and frightened. I followed it to a clearing and found a creature huddled against a log, about the size of a medium dog, covered in dark brown fur, matted with mud.

At first, I thought it was a bear cub. But as I approached, I realized the proportions were wrong—the limbs too long, the hands not paws but hands, almost human-like. The face was different, too—young, but unmistakably not a bear. It looked at me with dark eyes, full of fear but also intelligence. The kind of recognition you see in primate eyes, not wildlife.

I spoke softly, keeping my distance. The creature whimpered, injured and alone, favoring its left arm. In forty-three years, I’d seen abandoned wildlife before, but this was different. The injury, the distress, the location near water, and the impossible nature of what I was seeing made me break protocol. I was looking at something that didn’t fit any known species—something young, helpless, and impossible.

I approached slowly, speaking gently. The creature didn’t run, watching me with those intelligent eyes. I stabilized its arm with a splint made of sticks and medical tape. It flinched but didn’t resist, almost as if it understood I was helping.

The bigger question was what to do next. Standard protocol would be to contact Park Wildlife Services, but this was no ordinary discovery. I decided to bring it home, radioing Dorothy: “Found something unusual on patrol. Need your help.”

When I arrived, Dorothy was waiting on the porch. She took one look at the creature and said, “Otis Barnes, what in God’s name did you bring home?” I explained, and she examined it carefully—her nurse’s eye noting the anatomy, the hands, the face.

“If this is a bear cub, it’s the strangest bear cub I’ve ever seen,” she said. “So, what do we do?”

We brought it inside, set it on the living room floor. The creature emerged from the backpack, looking around our cabin with curiosity and weariness. It was maybe two and a half feet tall, fur dark brown with lighter patches, hands with five fingers and opposable thumbs. The feet were broad and flat, adapted for walking upright, though it moved on all fours like a toddler.

“It’s a baby,” Dorothy said softly. “Look at the proportions. The motor control. Can’t be more than a few months old.”

Which raised the question—where was the mother?

The creature made a sound, not distressed but communicative, looking at us with obvious intelligence. “It’s hungry,” Dorothy said, and brought it a bowl of milk and sliced apples. It ate delicately, using its hands, drinking carefully.

We set up a makeshift bed in the spare bedroom, lined with blankets, and the creature curled up and slept. Dorothy and I stood in the doorway, watching the impossible thing sleep in our daughter’s old room. “What did we just get ourselves into?” she whispered.

“Dorothy, what if the mother comes looking?” I said. “What if there’s a full-grown version of this thing out there, searching for its baby?”

“Then we return it immediately, no questions asked.”

It seemed reasonable—until midnight, when something massive began circling our house, making sounds that sent primal fear down my spine.

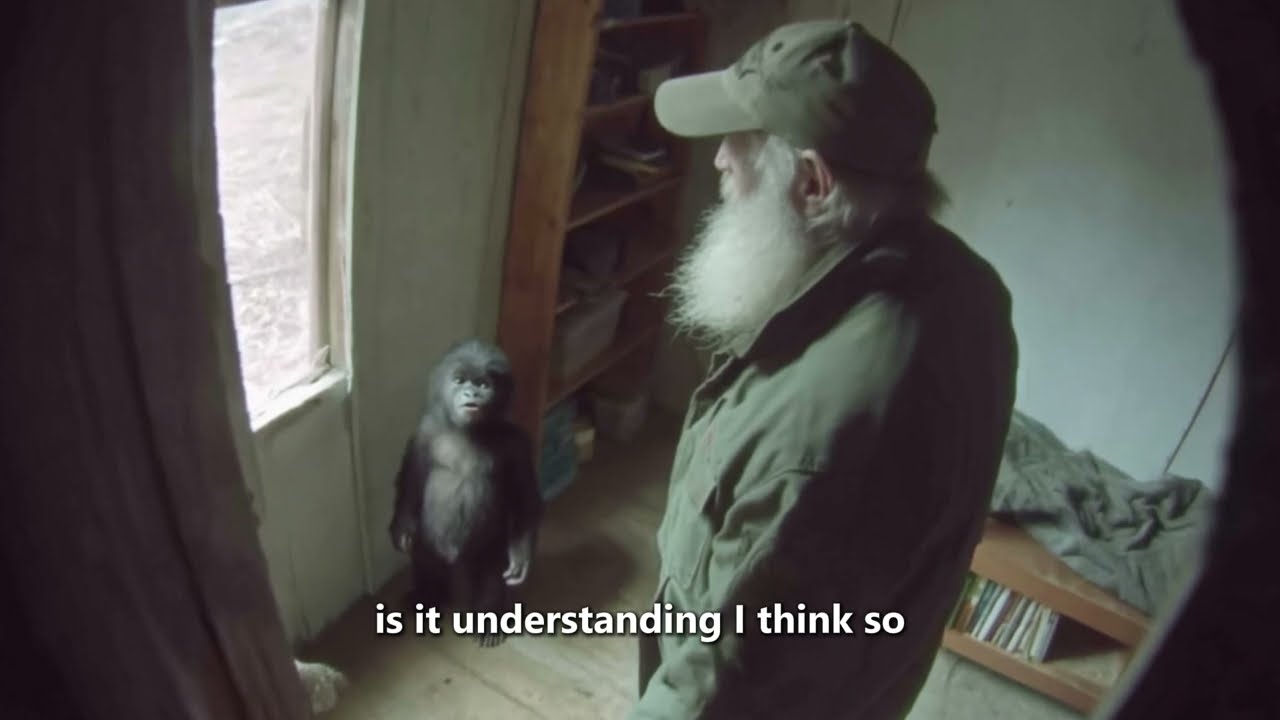

The creature slept through the afternoon, waking around four and exploring the bedroom. When I sat with it and showed it a children’s book, it responded with clear comprehension, pointing at pictures, making sounds of recognition. Dorothy watched in awe. “That’s not instinct. That’s comprehension.”

We named him Olly. He bonded with us, exploring the house, fascinated by music and routine. But as night fell, I worried about what might come looking for him.

At 11:30 p.m., I heard a rustling outside—deliberate, careful movement, circling the cabin. Not a bear, not an elk. Then a vocalization—deep, resonant, not a roar or scream, but something in between. Dorothy gripped my arm. “That’s not an elk.”

Massive hands touched the cabin walls, searching, feeling. Olly responded from the spare bedroom, chirping and calling back. The sounds outside changed, gentler, questioning.

“She’s calling to her baby,” Dorothy whispered. “It’s the mother.”

Then came a sound at the door—a scraping, then knocking. Not claws, knuckles. She was knocking, asking for entry.

I picked up Olly, who chirped uncertainly, caught between wanting his mother and feeling safe with us. I opened the door.

She was enormous—seven and a half feet tall, massively built, covered in dark fur lighter around the face and chest. Her eyes met mine, full of intelligence and weariness.

She made a gentle sound, a question. I held out Olly. He reached for her, and she took him with terrifying but gentle hands, cradling him, examining his splinted arm, making soft sounds of reassurance. Olly chirped back, touching her face.

Then she looked at me—recognition, gratitude in her eyes. She reached out and touched my shoulder, a gesture of thanks. Then she disappeared into the forest, leaving only enormous footprints in the soft earth.

Dorothy and I stood in the doorway, shaking. “We just returned a baby Bigfoot to its mother,” she said.

“Yes, we did.”

We sat in the living room until dawn, unable to sleep, processing what had happened. At sunrise, I went outside to examine the evidence. The footprints were real—eighteen inches long, five distinct toes, a flexible arch. Not bear, not elk. I photographed them, measured them, then faced a decision that would define the rest of my career.

I could report it—call headquarters, document the discovery. It would be the most significant biological find in history. But I remembered the mother’s gentle touch, the intelligence in her eyes, the consequences of exposing them. The park would be swarmed. Their lives would be destroyed.

Dorothy joined me. “What are you going to do?”

“I’m not reporting it. Not officially. My duty to living beings with intelligence supersedes my duty to protocols.”

We kept the secret. Over the next weeks, I found arrangements along the creek—stacked stones, berries, handprints. Signs of communication, of gratitude. I documented them privately, left them undisturbed.

As my retirement approached, I worried about who would come after me. The new ranger, Kevin Foster, was young, eager, scientific. He noticed the arrangements, wanted to document everything. I discouraged him, but knew he’d eventually find the truth.

When hikers reported strange sounds and Kevin found footprints, I made a choice. I showed him my evidence, told him everything. He listened, wrestled with the implications, then agreed to protect them.

On my last patrol, Kevin and I found a final arrangement—two handprints in the snow, mother and child, a farewell. I retired, knowing I’d done the right thing.

Now, as a civilian, I walk these mountains, knowing what’s out there, trusting that the secret is safe. Some truths are better protected than revealed. Some beings deserve to remain impossible. That’s my legacy—not forty-three years of documented service, but the few months of undocumented protection. The choice to value life over discovery.

And every time I walk in those mountains now, I feel like I’m walking on sacred ground—shared with intelligence that chose to reveal itself briefly, then retreat back into legend, where it belongs, where it’s safe, where it can raise its young and live its life without becoming humanity’s next conquest.

That’s enough. More than enough. That’s everything.