“Please Don’t Beat We Are Already Injured” Twins Whispered To Giant Rancher After Two Nights Of Fear

.

.

“Please Don’t Beat Us, We Are Already Injured,” the Twins Whispered

The morning air was thick with silence, the kind that settles before the sun has fully claimed the land. Out on the ranch, dewless grass clung to last night’s dust, and the earth smelled faintly of rain that had come and gone. Along the fence line, a giant of a man moved—his shadow stretching long across the field, boots pressing deep and steady marks into the soil. His hands, broad and scarred by years of labor, rested on the rails as if the fence itself deserved conversation.

It was in that hush, between the first bird’s call and the gentle stirring of breeze, that he heard it—a sound too small for such a wide land, a whimper barely more than breath. He stopped, turning his head, ears sharpening not from curiosity but from memory. He knew that sound; he had made it himself, long ago, when hunger and fear met in the dark corners of childhood.

The sound came again, from a hollow log half-rotted at the edge of a clearing, where moss and shadow made their home. He approached, each step heavy enough to stir dust but gentle enough not to scatter what might be hiding. His hand hovered at his belt—not for the gun, but for steadiness, because this was no animal’s cry.

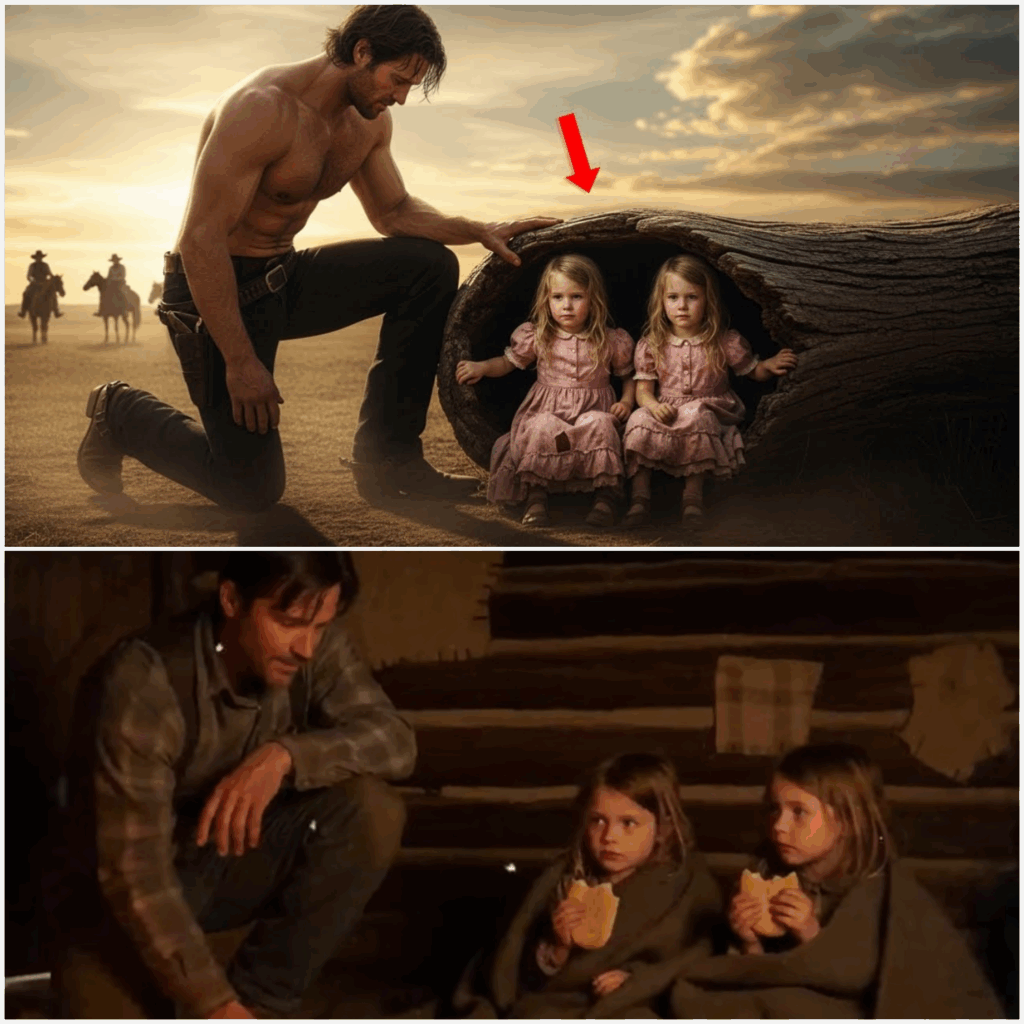

Two faces appeared, pale as ghosts, pressed close together in the hollow dark. Their eyes were too wide, too weary for children so small. Cheeks streaked with grime, hair tangled with leaves, and dresses that might have once been bright but now hung in tatters. They looked like sparrows blown from their nest, trembling in a fallen branch, and they did not move until his shadow swallowed the log’s opening.

He crouched, lowering himself so his size would not frighten them more. Silence stretched between them, heavy as judgment. Then, one child, no taller than his knee, lifted her chin, lips trembling as if words might cut her tongue. The whisper broke the air like a twig against stone.

“Please don’t beat us. We are already injured.”

The words struck him harder than any bullet. He saw in them the sting of belts, the burn of ropes, and the old taste of copper when blood runs from the mouth. His throat closed up, the giant of him undone by a sound smaller than a bird’s cry. For a long moment, he said nothing. Words had never been his trade—only the steady rhythm of work and the honesty of a back bent to earth.

He looked at their arms, thin and marked, knees scraped raw. In their stillness, he saw himself—a boy once pressed into corners, asking no one in particular to spare him. He extended his hand, slow as dusk slipping into night. The children flinched, pressing back into the hollow, but he left his hand open and unhurried, offering not command but choice.

They watched him as if the world might end with a wrong move. Then, with the smallest courage born of desperation, one reached out, laying her tiny palm against his rough skin. He did not close his hand over hers. He only lifted, careful as if carrying water in a cracked bowl. The second girl followed, clutching the fabric of his shirt with surprising strength.

He rose, carrying them both—one tucked against each arm, their bodies light as kindling, though far more fragile. The log behind them remained hollow, but it no longer held fear; it held only the echo of a night survived.

His cabin was not far, though to the children it must have seemed the whole world away. They did not speak as he walked, their heads pressed against his shoulders, but their eyes remained open, watching the sky as though to mark the path. He felt their breaths against his neck, shallow and uncertain, as though still bracing for pain.

When the cabin came into view—rough-hewn logs, a patched roof, smoke curling faintly from the chimney—they stirred but did not resist. He pushed the door open with his boot, the hinge sighing, and stepped inside. The room smelled of woodsmoke and coffee long cooled. A table stood scarred by years of use, a single chair pulled close, the hearth aglow with the faint embers of last night’s fire.

He set the children down near the warmth, watching as they folded into themselves, small backs bent, hands tucked against their knees. They did not look at him. He filled a tin cup with water from a jug and set it on the floor before them. They glanced at each other, uncertain, then one leaned forward, sipping quick as if the drink might be stolen. The other followed, wiping her mouth on the back of her hand.

He turned to the shelf, pulled down bread—hard, but still bread—and broke it into pieces, laying them out. The children snatched at it, stuffing their mouths, chewing fast. He did not stop them, though he knew the pain of eating too quickly. Hunger was its own teacher.

As they ate, he sat at the table, his eyes fixed not on them but on the window, where morning light began to pierce the glass. He thought of the talk that would come if he led them into town—a man alone with two children, no wife, no kin. He could already hear the whispers, questions heavy with suspicion, judgments sharper than blades. But he also thought of the words that had greeted him at the log. Please don’t beat us. Words too old for such young mouths.

When the bread was gone, the girls curled against each other, exhaustion pulling them down. He rose, gathered blankets from his bed, and laid them gently over the small forms. They did not stir. Only the rise and fall of their breaths assured him they lived. He stood over them, a mountain of a man whose heart beat unsteady in the quiet. He had not chosen this. The world had placed it before him, as it so often did—burdens, tests, mercies hidden as trials.

He could walk away. He could carry them into town, hand them to whoever claimed them. It would be easier, safer. But as he turned toward the door, the smaller of the two stirred in her sleep, a hand slipping free of the blanket. Without thought, it found his boot, tiny fingers curling against the leather as though anchoring themselves to something solid. He froze, breath caught, and for the first time in years, he felt the tremor of tears rise unbidden. He looked down at the fragile grip and knew, whether he wanted it or not, the hollow log had given him more than children. It had given him a choice he could not escape.

The next day, the girls moved quietly about the cabin, their fear not yet gone but softened by routine. He showed them how to sweep the hearth, how to scatter grain for the hens, how to brush the old horse’s mane. Their laughter came more often now, light and sudden, like sunlight breaking through cloud. It stitched small seams in the fabric of his days—seams he had not known were missing.

Yet even in their laughter, he saw the flinch whenever footsteps approached or a shadow passed the window. One evening, as dusk settled, the girls placed a broken doll in his hands, its stitched dress already fraying. He threaded the needle once more, his fingers clumsy but careful, and when he returned it, they held it as if he had handed them proof that something broken could still be made whole.

But the world outside did not forget. Gossip grew like tumbleweed, rolling into every corner. One night, a knock sounded at the door—firm, carrying the weight of certainty. A lean man stood there, his face carved from bitterness and whiskey, boots scuffed from wandering.

“They’re mine,” he said. “Blood calls for blood. Hand them over.”

The twins clung to each other, their bodies trembling with dread. The rancher filled the doorway, his body a wall between the intruder and the children.

“They’re safe here,” he said, his voice steady as stone.

The man sneered. “Safe with a stranger? The sheriff will hear of this. Blood’s mine. Doesn’t matter if I spill it or spare it. They’ll come back with me.”

“They’re not going anywhere with you.”

The man spat, rage brimming. “This ain’t done. Sheriff will be here by sundown tomorrow.”

When the sheriff arrived, his coat heavy with authority, he listened to both sides. The girls, trembling, told the truth. “He hurt us before we hid. We don’t want him, please.”

The sheriff’s eyes softened. “Blood ain’t claim enough to chain a child. The law won’t carry them back into harm.”

The lean man rode off, curses lost to the wind. The sheriff turned to the rancher. “You’ve taken on a heavy load. But it’s yours now, if you mean to keep it.”

The rancher nodded, his silence carrying the weight of a vow.

That night, the girls curled against him, their small fingers wrapped around his hand. The cabin, patched and weathered, breathed with new life. It was not a mansion, nor a promise shouted loud. It was a bowl of spaghetti on a wooden table, the soft laughter of children finding home, and the way trust grows not with speed, but with sincerity. And as the windchime sang low on the porch, the hollow log in his memory emptied of fear, filled instead with hope being born.

.

play video: