THEY TIED HER DOWN WHILE HER PUPPIES WERE HURLED INTO THE RIVER… BUT THE NIGHTMARE WASN’T OVER YET

.

.

They Tied Her Down While Her Puppies Were Hurled Into the River… But the Nightmare Wasn’t Over Yet

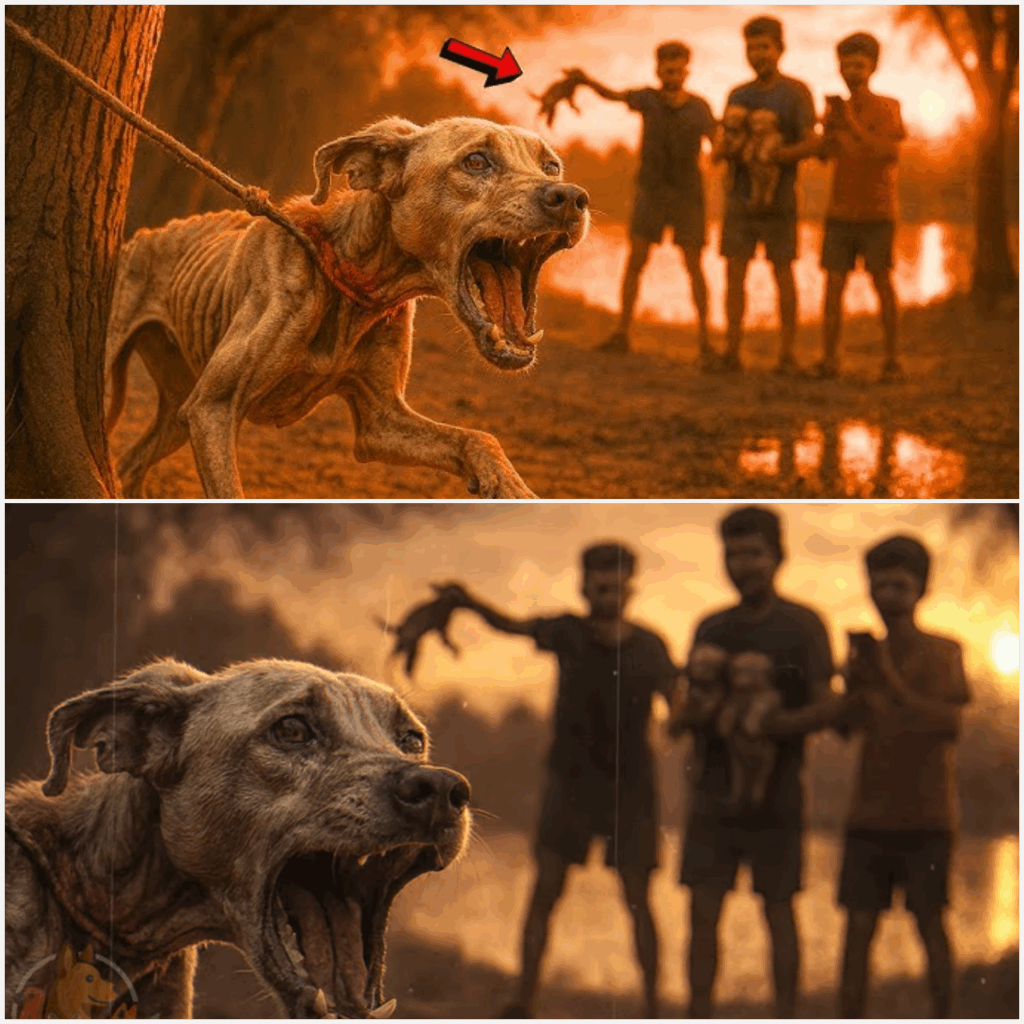

The rope cut deeper each time she lunged. Mud caked her paws. Nails scraped stone. Breath tore out of her like fabric. Across the shallow creek, three boys stood on a shelf of rock, a phone held high, laughter echoing in hard bursts. One boy grabbed a pup by the scruff and swung, as if skipping a stone. The splash was small. The current took it. The mother dog didn’t bark. She made a noise from somewhere older than language, eyes fixed on the water as if she could will it to spit her child back.

A man on the shoulder of the county road stopped mid-step. He wore work boots and a gray t-shirt with a hardware logo. Coffee dropped from his hand and burst in brown petals on the gravel. By the time the cup rolled into the weeds, he was already running.

“Hey!” he shouted, closing the last yards. “Stop!” One boy flinched. Another lifted the phone higher, framing the man like new content. The smallest boy, freckled, sock soaked, had the last pup in his grip, arm cocked like a pitcher.

“Put him down,” the man said, breath sharp but even. The kid hesitated. The pup trembled, stomach pasted to the boy’s dirty forearm. The mother hit the end of the rope so hard her front legs flew. She crashed, scrambled back up, hit it again, a raw groove ringing her neck where fibers had already eaten skin.

“Now,” the man said. The smallest kid crouched and set the pup in mud, hands shaking like he’d never used them before. The man slid in, scooped the tiny body to his chest, felt a heartbeat smack against his palm like a fish.

“You insane?” the oldest kid said, trying on a tone he’d heard somewhere. The man didn’t look at him. He nodded at the post that held the rope. “Untie it.” No one moved. He shifted the pup into the crook of his arm and went himself. The knot was old and mean. He dug with his house key, jaw set. The mother lunged again and almost choked herself.

“Easy, mama,” he said, not taking his eyes off the knot. “Hang on, you’re going to get bit,” the phone kid said, but there wasn’t confidence in it anymore. Metal bit twine. The knot gave. He yanked the rope free and let it hit the ground like a dead snake.

The dog surged, not at him, but past him toward the water. He dropped to block her, hand to her chest. “No, girl. No.” The creek ran brown and fast from last night’s rain. Two small ripples were already gone, where the current slid under sycamore roots. He set the rescued pup down, pressed along the ribs, head down. Three firm strokes to clear water, the way a nurse had shown him years ago. A cough, a pin-sized sound, another. The tiny chest fluttered.

He waded in anyway, jeans dragging at his legs, cold taking his breath, fingers sweeping a fan over the bottom, rocks a tangle of weeds, then a limp weight. He pulled it free, carried it to shore, worked it with careful pressure, counted breaths against time he couldn’t hold back. The pup didn’t return. He laid his own t-shirt over the small body as if covering it could change something.

The boys had gone silent. The oldest swallowed hard. The phone lowered like it weighed more than a hand could manage. The smallest kid stood with his arms dead at his sides, eyes on the shirt. The man took out his phone with mud-slick fingers and dialed.

“911. Animal cruelty. Miller Creek Bridge, County Road 12. Three male juveniles. One deceased animal, two living, mother injured. I need animal control and a unit.” He gave his name, Caleb Reed, and ended the call.

The mother pressed her nose to the breathing pup. The tremor in her body made her teeth click. She wasn’t wild. She was target-locked. She looked at the water again. Then she looked at Caleb and held. He saw more than pain there. Direction. The feeling you get when someone points without moving a hand.

Sirens stapled the distance into smaller pieces. The boys stared at the gravel like it could swallow them. “Sit,” Caleb said to them, voice flat. They sat. A county cruiser slid onto the shoulder, dust lifting around it. A deputy stepped out, hand near holster because training lives in muscle. He took in the scene in one sweep. Rope on mud, shirt on bank, boys, man barefoot in the creek, dog with raw neck, and his shoulders squared to the moment.

“You the caller?” he asked.

Caleb nodded. “Two alive, one gone. She was tied to that post.” The deputy radioed in, then separated the kids with practiced calm. An animal control van rolled up, white with a dent in the side door and a tech in a navy polo. Garcia, stitched above the pocket, knelt where the mother could see her hands.

“Hey, mama,” she said in a tone that made distance shorter. “You did good.” Garcia looped a soft lead over the dog’s head without pressure, just offering a circle. The dog let it settle. She didn’t strain now. She stood with every nerve open, eyes still cutting between creek and the tiny body against Caleb’s jacket.

The deputy bagged the phone the oldest kid handed over without being asked. He got names. Tyler, Jace, Brandon. He wrote them down, each letter a little heavier than the last. Caleb’s cold turned to shiver. He stared downriver. The dog did too. Not at the spot where the current had taken what she couldn’t get back, but farther past the bend where the creek narrowed into a seam between trees. She lifted a paw, lowered it, lifted it again.

Garcia noticed first. “You seeing that?” Caleb nodded. “She’s showing us something.” The deputy weighed it in a heartbeat. “Statements, scene, procedure, then what stood alive in front of him. We can follow along the public right of way,” he said. “No fences without consent. Mr. Reed, you stay in sight.”

They moved. Weeds slapped calves. The creek hissed under roots. The dog stepped, waited, looked back to make sure they were with her, then stepped again. When they reached the bend, she stiffened at a slumped chain-link fence. Beige fibers clung to the wire. Rope frayed just like the one on the bank.

Garcia took photos. The deputy keyed his shoulder mic. “Unit 12 tracking evidence down Miller Creek.” Caleb crouched. The fibers felt like they had a history. They slid through a gap where the fence had collapsed. On the left, scrub, a stack of plastic crates, a blue top hung off a patched lean-to. On the right, a field of weeds leading to a trailer that had seen too many summers. Bowls in the shade, a coil of rope on a nail, frayed.

The dog pulled, not frantic, guided toward the lean-to. The deputy lifted a hand. “Hold. Private property.” Garcia stopped. Lead loose. The dog leaned into it like a compass leaning north. A man in a ball cap stepped from behind the trailer. Mid-40s, thick through the middle, eyes that skipped.

“You folks lost?” he said.

“Afternoon,” the deputy answered. “You the owner?”

“On paper,” the man said. “What’s it to you?”

Garcia glanced at the bowls and the rope. “We had a cruelty call upstream,” she said. “Your fence abuts the creek. You keep dogs here?”

“I keep what I keep. You got a warrant?”

“Not yet,” the deputy said. “We’re not entering.”

The dog eased her muzzle to the lowest rail of the fence and let out a sound that carried straight through bone. The man didn’t look at her. Caleb did. He lay flat and peered under the lean-to through a shallow hole dug at the fence line. Inside, in shadow, he saw crates stacked two high, rust flaking. In the far crate, eyes like coins caught the light.

Garcia’s voice stayed even. “We’ll need to follow up.”

The man’s mouth went flat. “Name’s Lawson,” he said. “Be quick.”

The deputy answered his radio and said words that meant warrant. Garcia kept her camera up. Caleb kept his breath measured, mud drying on his skin like armor he hadn’t asked for. The dog stayed leaning on that invisible north.

When the deputy said, “I’ll be back with paper,” Lawson’s lips pulled to the side. Not a smile, a timeline. The dog never looked away from the gap. Caleb felt heat settle in his chest and cool at the same time, like someone had set a tool there he would have to learn to use.

“We’re not done,” he said, barely above a breath.

They didn’t move from the fence because the dog wouldn’t. She stood with her chest almost touching chain link, eyes fixed past the gap, ears pricked to small sounds moving behind wood and shade.

Garcia kept the soft lead loose, one hand comforting without claiming. Caleb filmed the red dot—a witness that didn’t interrupt. “Keep to the creek side,” the deputy said. “Document. No stepping over until I’m back with a signature.” Lawson stayed just inside his yard line, hands in pockets, hat brim low. His eyes tracked Garcia’s lens and skipped over the dog. He had the look of a man who’d already decided what reality he’d accept.

The creek licked at a small dam of trash where the fence dipped. The dog drifted two posts down and sniffed where a thin stream leaked under chain link. It smelled like hose water and bleach. A black plastic bag had snagged in weeds there, ballooning and collapsing with the tug of the current.

“In water? It’s public,” Garcia said, kneeling to snap a photo. “Don’t rip it.”

Caleb stepped into the shallows. He caught the bag at the knot and dragged it up the bank. It was heavy in a way that spoke of metal and time. Garcia gloved up, peeled plastic back an inch at a time. Inside, nylon straps tangled red, blue, tan. Collars, dozens, tags ground to blank ovals. In the mess, a chewed pink strap like a memory that refused to die.

Lawson’s jaw went still. He looked at the road as if traffic could erase this. Garcia didn’t look at him. “Multiple collars,” she said for the mic, “tags defaced, disposed adjacent to abutting property.” She eased out a small spiral notebook soaked but legible in places, columns marked with dates, letters S, L, and a third, DT. She bagged it separate, vents open so the pages could dry without molding into lies.

The dog dipped her muzzle into the pile and nudged the pink strap toward Caleb, then looked into his face. He didn’t need narration. He filmed the strap, the raw ring on her neck, the way she held herself steady and refused to be cheapened into panic.

The rest of the story unfolded in the slow, methodical way that healing does. Law enforcement returned with a warrant. The lean-to was searched. More dogs, more pups, crates, evidence. Lawson was charged. The boys faced consequences. The mother, named Miller at the shelter, curled herself around her pups, and Caleb, who had only meant to stop for coffee, found himself returning every day to sit on the floor, to be boring, to let trust grow.

Tyler, the boy who’d let the last pup go, came to the shelter too—at first as a sentence, then as a choice. He learned to fold towels, to scrub bowls, to apologize not with words but with attention and care. Garcia, the animal control tech, ran the shelter like an air traffic controller, routine as mercy, paperwork as promise.

Miller healed. The scar around her neck faded. Her pups grew, found homes. Caleb fostered her for a time, learning that stewardship is a kind of love that doesn’t own, only carries across rough water. When a kind couple came, with soft voices and boots that had known mud, Miller chose them. Caleb let her go, not with grief, but with the quiet satisfaction of someone who did not look away.

The nightmare was over, but the work continued—at the shelter, in the courtroom, in the daily acts of care that make repair possible. Caleb washed bowls, Tyler mopped floors, Garcia moved through the building with a clipboard and a nod. Miller slept in a real bed, her body stretched long and unafraid.

Some stories don’t end with rescue or revenge. They end with small, steady acts of repair, with a town that chose not to look away, with a dog who learned to sleep without fear, and with people who learned that sometimes, the most important thing you can do is simply to keep showing u

.

play video: