Japanese War Bride Married a U.S. Soldier in 1945 — Her Children Only Learned Why After Her Funeral

In the quiet aftermath of World War II, Fumiko Nakamura arrived in America with little more than a suitcase and a new name. To her husband, she was Francis Whitlock, a devoted wife from Iowa. But in the ruins of Hiroshima, she had been Fumiko, a young woman scarred by unimaginable horror. For decades, she carried her secrets like a silent burden, shielding her children from the truth of her past. It wasn’t until after her funeral that her family unlocked a hidden box, revealing the depth of her sacrifice. This is the poignant tale of a survivor who endured the atomic bomb, crossed oceans for love, and spent a lifetime concealing her pain from those she cherished most.

August 6, 1945, dawned like any other in Hiroshima. Fumiko, just 19, awoke in her family’s modest wooden home, a two-kilometer walk from the city center. The house, a three-generation legacy, offered simple comforts: sliding paper doors, tatami mats, and a garden where her mother Hana tended vegetables and flowers. Her father, Kenji, a respected schoolteacher, penned poetry by candlelight, his brush strokes elegant and deliberate. Her mother sold produce at the morning market, her kindness a neighborhood staple. Older brother Teeshi, 23, worked at the post office, secretly studying medicine in hopes of a postwar university. Wartime life had normalized fear; air raid sirens wailed nightly, but false alarms dulled the edge.

That Tuesday, Fumiko was slated to help at the market, honing her skills in negotiation and display. But her aunt Tomoko fell ill in a village 30 kilometers east, prompting Fumiko to board an early train with rice balls, medicine, a poetry book from her father, and calligraphy supplies. She had plans to meet friend Akiko for practice—calligraphy was her passion, a rare path for women, with Master Yamamoto praising her talent. Irritated by the detour, Fumiko gazed out the window at rice fields and birds, the train half-empty with elderly farmers. At 8:15, the world shattered.

A blinding flash turned the sky white, searing her eyes. Shockwaves rattled the train like a giant’s fist, shattering windows and hurling glass. Fumiko curled under her seat, bleeding from cuts, as screams filled the air. The train halted; passengers emerged to a mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima—black, red, orange, purple—impossibly vast, blotting the sun. Rumors swirled: a bomb, the Americans’ wrath. Fumiko’s stomach churned—her family was there. Legs numb, she leaped off and ran, collapsing after an hour, aided by Mr. Sato, a bicyclist who warned the city was gone. He ferried her closer, where the air reeked of burning metal and flesh, ash snowing like death. Survivors staggered, skin peeling, hair gone, eyes vacant. Fumiko pleaded for news of the Nakamuras—no answers, only moans.

For three days, she searched the obliterated city, sleeping amid corpses, drinking contaminated water, pulling bodies from rubble. No trace of her family remained; they had vanished in vapor. Exhausted, she sat in presumed ruins, praying for death, but her body endured. By August’s end, she resided in a refugee camp, amid the sick—hair falling, skin blackening, vomiting blood, bleeding inexplicably. Doctors dubbed it radiation sickness, helpless against the agony. Fumiko starved herself, silenced by grief.

September brought American forces under General MacArthur. Fumiko despised them—they had wrought this devastation—but survival demanded compromise. She worked in a military kitchen in Kure, scrubbing pots, peeling potatoes, avoiding soldiers’ gazes. There, she met Earl Whitlock, a 23-year-old private from Iowa, sandy-haired and boyish, handling supplies. Unlike others, he smiled politely, thanked her daily, his broken Japanese earnest. His kindness infuriated her at first—how dare he act normal? Yet he persisted, bringing chocolate, fruit, gloves for her cracked hands, an English phrase book. His gentle persistence chipped at her armor.

By spring 1946, conversations flowed. Earl shared Iowa’s cornfields and family farm; Fumiko revealed little, her story ending August 6. He didn’t press, offering solace in mundane talk. By summer, love blossomed, terrifying her—a betrayal of the dead. But Earl felt safe, his patience reviving her humanity. In July, by the harbor, he proposed in halting Japanese. Fumiko wept, citing impossibility, hatred, her emptiness. He countered: he wasn’t his country, just a man who loved her. For the first time, she glimpsed a future.

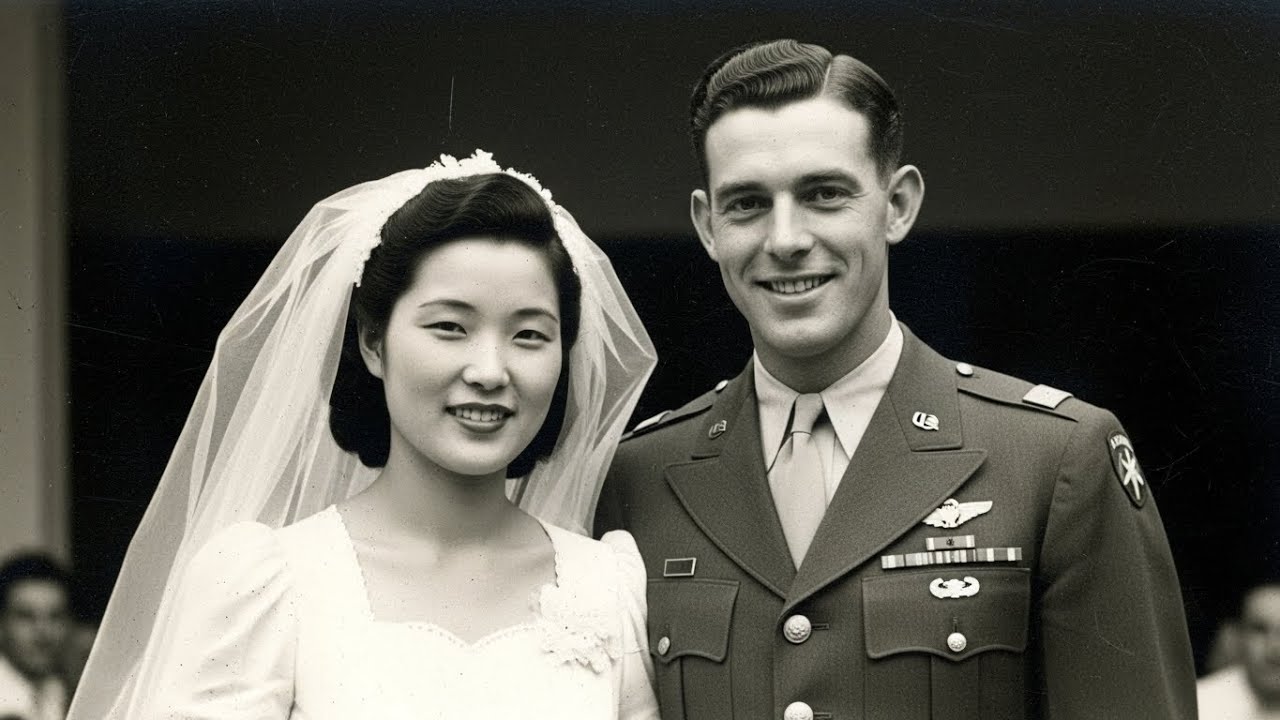

Marriage faced barriers; the military banned unions with Japanese women, deeming them traps. Earl fought tirelessly—letters, arguments, research. Fumiko watched his devotion, deepening her love. The 1947 Soldier Brides Act enabled it, though bureaucracy humiliated her with exams and affidavits. Earl navigated it all, bribing with cigarettes, calling favors. In November 1947, they wed in a Kure chapel—Fumiko in a borrowed dress, Earl’s buddies as witnesses. No family; her past erased. It was real, if foreign.

Early 1948, Fumiko boarded a ship to San Francisco, seasick amid war brides’ chatter and tears. America overwhelmed: towering buildings, wide streets, confident crowds. Earl held her hand; they lingered for his discharge, visiting the Golden Gate Bridge, savoring ice cream bittersweet with loss. A train carried them east through snowy mountains, deserts, plains—America vast, swallowing. Fumiko memorized her new identity: Francis Whitlock, Hiroshima’s Fumiko dead.

Fairview, Iowa, greeted them coldly. Population 1,800, farms and judgment. Earl’s parents—stern Ruth, silent Harold—offered frigid welcomes. The farmhouse felt alien; disapproval palpable. Their rental house, tiny but theirs, offered solitude. Fumiko erased herself: short hair, American clothes, louder speech, perfect English. She burned mementos—letters, photos, calligraphy—declaring the past gone. Earl mourned silently.

Pregnancy in 1950 terrified her; motherhood without guidance. Earl rejoiced, preparing the nursery. Dorothy Ruth Whitlock arrived June 14, blue-eyed, dark-haired—hope reborn. Fumiko vowed her American life, shielding her from hatred. The town softened post-birth, bringing gifts. Fumiko embraced homemaking: spotless home, elaborate meals, handmade clothes. Francis eclipsed Fumiko.

Warren Harold followed in 1953, quieter, observant. Life blurred with chores, school, church. Fumiko stayed busy, avoiding thought. By the 1950s, she perfected her role: fluent English, ribbon-winning pies, garden, polite children. But sadness lingered in her eyes; children noticed her flinches at Hiroshima mentions.

Doie graduated 1965, teaching like her unknown grandfather. Warren, 1971, studied WWII history, fascinated yet oblivious. Vietnam loomed; college deferred the draft. Thanksgiving 1971, a Hiroshima book triggered Fumiko’s panic—she fled, locking herself away. Warren sensed secrets.

Doie married Robert Chen in 1972, a Chinese-American understanding prejudice. Fumiko regretted her silence, perhaps robbing them of roots. Earl’s 1975 heart attack devastated her; 28 years of love, yet untold truths. Post-funeral, she withdrew, staring out windows, tending secret Japanese vegetables.

The 1980s isolated her; Berlin Wall fell, but she remained frozen in 1945. Grandchildren visited, but she distanced, fearing questions. 1989 cough worsened; lung cancer diagnosed, stage 4. Calmly, she refused treatment—tired, ready. Doie cared for her; Warren visited. They urged sharing; she smiled, loving them.

Final weeks, Fumiko pondered Chio, her Osaka sister, who searched post-war, writing 40 years. Fumiko read but never replied—cruel silence to survive. Regret now futile.

Fumiko died March 12, 1990, 63, whispering Japanese farewells. Funeral honored Francis; mourners unaware of Fumiko. Doie and Warren, grieving a stranger, found the box: kimono photo, Chio’s letters, calligraphy, origami, military ID. Tears flowed; they grasped her solitude.

Warren hunted Chio, finding her in Hiroshima. She wept, sending photos, stories. They visited 1991, meeting at the Peace Memorial. Chio showed the park where home stood, museum horrors. She gave a 1949 letter: Fumiko’s plea to forget for survival. Ashes scattered; Fumiko rested as herself.

Back home, Warren wrote about war brides; Doie funded scholarships. Children learned truth. Fumiko’s story echoes 50,000 Japanese brides’ sacrifices—discrimination, buried trauma. They crossed oceans for love, paid with silence. Survivors, mothers erasing selves for children’s futures—their legacy endures, a testament to resilience and the quiet heroism of those who rebuild from ashes.