18-Year-Old Girl Thrown Off Cliff for Refusing to Marry Sheriff, Until Comanche Man Shocks Everyone

.

.

Thrown from the Cliff for Refusing the Sheriff — Until the Comanche Man Shocked Everyone

The wind that morning didn’t howl. It whispered, like it knew what was about to happen and didn’t want to interfere. Five men led her up the cliff in silence, their boots sinking through knee-deep snow. The youngest among them kept glancing back, jaw tight with something close to guilt. The oldest never looked down at her, not once. They moved with the steadiness of men who had already made their choice, minds sealed off from second thoughts.

The girl was barely more than a child—eighteen, with auburn curls hidden beneath a burlap sack tied around her head. Her hands were bound in front, wrists red and raw from earlier struggle. Her blue calico dress was torn at the shoulder, bruises on her cheek, a gash above her eye where the sheriff’s ring had caught her bone. But it wasn’t the blood that struck the heart. It was the stillness. She no longer screamed. That part of her had gone quiet.

Sheriff Luther Cain rode behind, rifle across his lap, his horse breathing fog into the cold air. Cain’s face was unreadable beneath the brim of his hat, the gray in his beard powdered with snow. He hadn’t spoken since sunup, not since he declared before a room full of deputies and murmuring townsfolk that the girl had dishonored him and that no law would protect what law had already condemned.

Her name was Clara Rose McKinley, daughter of a carpenter, known once for her kindness, her humming voice as she hung laundry behind the church, for the pie she baked for widows who couldn’t rise from bed. That was before the sheriff took interest. Before he declared his intention to marry her. She had told him no softly at first, then firmly, and finally in front of others when he tried to put a hand on her waist at the town dance. The slap echoed—louder, perhaps, than her scream that morning when the sack was pulled over her head.

The trail narrowed near the top. A hawk flew overhead, its cry sharp and lonesome. The snow had turned to a fine powder, the kind that settles like ash. When they reached the edge, the cliff opened before them like a white wound in the world. Far below, rocks jutted through snow like broken teeth. There was no wind here, only silence, like the land was holding its breath.

The men did not look at her as they stopped. The youngest shifted his weight. One adjusted his gloves. One muttered a prayer. No one called her name. No one untied the sack. Sheriff Cain dismounted, walked forward, boots crunching. He did not touch her. He only leaned close and whispered something that made the youngest man flinch. Then he straightened, stepped back, and nodded.

And that was it. They pushed her. Not hard—just enough. As if she were a bundle of trash to be cleared, not a living thing with breath still in her chest, she stumbled, arms out, sack shifting as the world fell beneath her. And then gone.

The silence after was worse than a scream. Worse than gunfire. The men did not stay long. They turned back toward town without speaking. Cain rode in front this time.

But Clara didn’t die. The fall was steep, but not clean. There were gnarled branches, half-buried in snow, one of which caught her dress, ripping it but slowing her descent. Her body slammed against the rocks below, ribs bruised, leg twisted, but the snow cradled her in its cold arms. It wasn’t mercy—it was accident. But sometimes accident is all grace needs to enter the world.

She lay there as light faded, the sack still covering her face. Her breath came in short, panicked bursts, each one a cloud. She couldn’t move her leg, couldn’t scream. The pain in her ribs made breathing feel like drowning. But she was alive. That fact pulsed louder than the agony.

Far above, the town’s bonfire began to smoke. The day ended. They would return to their homes, eat stew, tuck children into bed. The sheriff would polish his badge.

A boy named Eli, sent into the woods for kindling, spotted something below the cliff as he searched for pine cones. He saw the red in the snow first, then the movement—a twitch, like a bird with a broken wing. His mouth dropped open. He dropped his basket and ran.

By nightfall, the cold crept deeper. Clara drifted in and out of waking, wondering each time if she’d gone under for good. Her fingers were going numb. Her thoughts became slow and watery. But even in that haze, one feeling stayed sharp—shame. Not for what she had done. She had done nothing. But for the way they had looked at her, like she was nothing, like she belonged to someone, and now she was ruined.

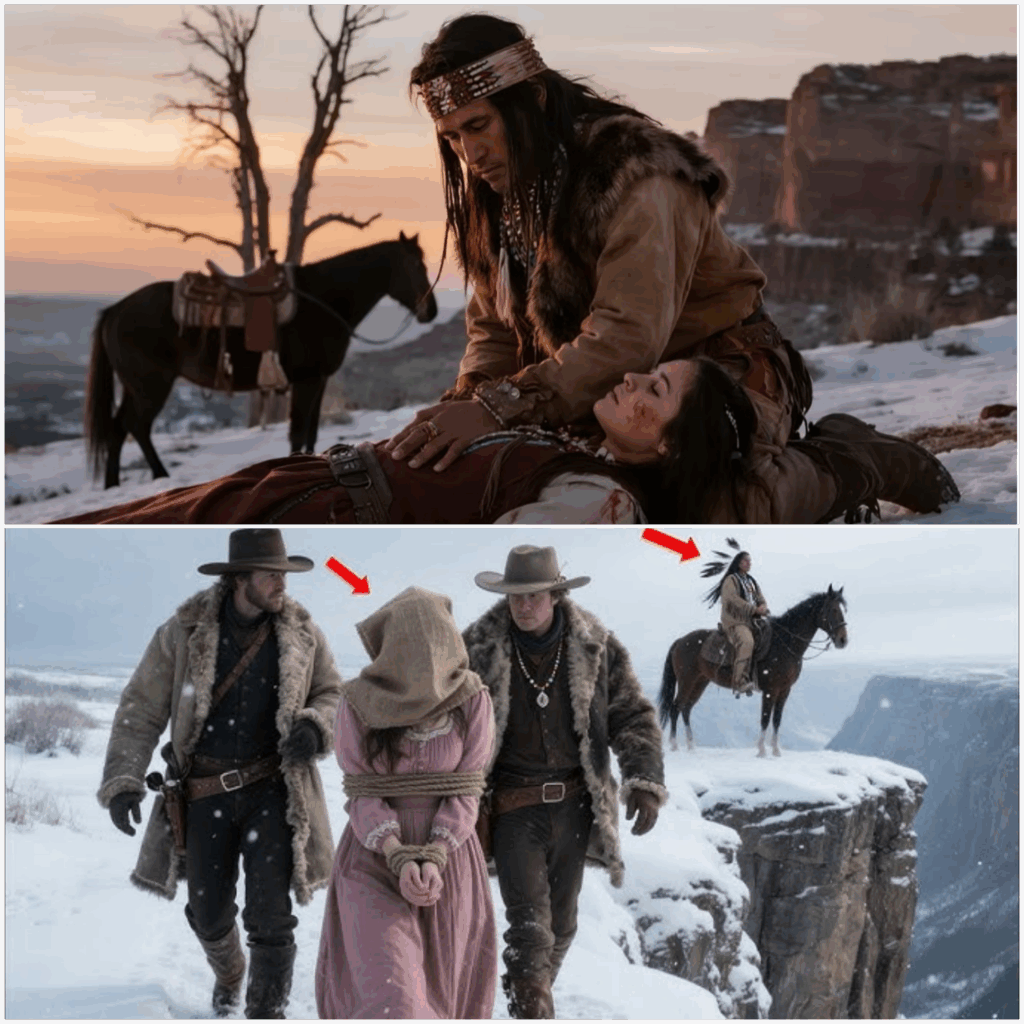

Snow began to fall again, gentle like forgiveness. A figure moved on the ridge—not one of the men from earlier, not anyone from town. A rider, tall, still, dark against the snow. He dismounted without hurry, tying his horse to a dead tree. His face was weathered, eyes deep and silent. He knelt beside her, lifted the edge of the sack carefully, like peeling back time. Their gaze met for a heartbeat. Then the world tipped again and she knew nothing more.

Somewhere someone lifted her. She felt warmth and fur and the scent of cedar. A voice not in English murmured something low. She wanted to ask who he was, but her throat would not obey. The rider placed her across his saddle, cradled like a child, and covered her with a blanket. Snow fell around them, not harsh, not cruel, just falling. He led the horse forward, not toward town, but away from it into the trees.

Behind them, the cliff remained quiet, still like it had never seen a thing. But the snow there would never quite look the same again. And the wind, when it passed through that place, sometimes carried the sound of a girl’s breath rising, defiant and alive.

She was not supposed to survive. But she did.

The snowfall thickened by morning, a silent siege upon the world. Trees bowed with its weight, their limbs stretched toward the ground like weary elders. The stream near the old Comanche trail had frozen to stillness, and not a single bird dared break the hush. Only hoofprints whispered across the landscape, deep, steady, unhurried.

Ronan Ghost Hawk rode through the snow without speaking to his horse. He didn’t need to. The stallion followed the path as if pulled by memory, not muscle. Ronan wore a buffalo hide coat stitched by his late wife’s hands, now weathered with years. Around his neck, a rawhide cord held an iron ring, too small for his finger, too sacred to bury.

He had not meant to return this way. The cabin he rode toward had been shuttered for three winters now, left behind when grief made even shelter unbearable. But something in the wind had turned his head, something beyond sight or reason. He trusted such instincts. They had kept him alive longer than bullets ever could.

It was the red that caught his eye—not bright, just a faint smear in the untouched snow. Like rust bleeding through white linen. He slowed the horse, dismounted, squatted low beside the mark. A torn thread of blue fabric clung to a broken branch. The snow here had been disturbed—unusual, too far from any trail. The cliff above loomed silent, pretending innocence.

And then he saw her, half-buried beneath frost and bone-colored drifts. Her body lay crooked, one leg twisted beneath her, one hand clawing into the snow as if she tried, even at the end, to rise. The sack still covered her face. Her chest barely moved.

Ronan’s breath escaped in one clouded sigh. He moved like a man handling sacred ground. First, he removed the sack. Her face was bruised, lashes iced, blood at her temple frozen into her hair. She was young, younger than his wife had been when she died. There was a line around her neck where the sack’s drawstring had rubbed raw. He touched her cheek—warmth, barely.

Ronan did not ask what happened. He had seen too much to need the full tale. The marks were plain—the sheriff’s rope, the townsmen’s silence, the kind of violence that wore law like a mask. He gathered her gently, one arm under her shoulders, the other beneath her knees. She moaned a soft animal sound but did not wake. Her weight was light—not the kind of light that meant youth, the kind that meant hunger.

Ronan laid her across the saddle, wrapped her in his coat, and mounted behind her. The horse turned east without instruction. The trail narrowed. Pines closed in. Snow clung to Ronan’s eyebrows and lashes, but his expression did not change. He kept one hand at the girl’s back, steadying her as they rode.

At dusk, they reached the cabin, tucked among trees like a secret kept too long. The door groaned when he pushed it open. Dust danced in the firelight from a single match. He laid her on a cot by the hearth, then lit the stove with trembling fingers. The cabin slowly inhaled warmth. He did not touch her again that night. Instead, he brewed a tincture from bitter root and pine. He stripped her boots carefully, noting the cracked skin, the blackening toes. She’d nearly lost her foot to the cold. He packed it in poultice, wrapped it in wool.

When she stirred, she whimpered, but her eyes did not open. He sat beside the fire and watched her. For two days, she slept, slipping between silence and fever. Ronan fed her broth through a carved spoon, whispered prayers in a language the town had long forgotten, and never once asked her name.

When she finally opened her eyes, it was evening. The cabin glowed golden orange with firelight. A stewpot bubbled quietly. Ronan sat in the far corner, whittling a piece of cedar. Clara’s voice cracked when she tried to speak. Nothing came out.

He looked up, set the carving aside, and approached. She flinched. He stopped midstep and lifted his hands, not in surrender, but in stillness. He offered a cup of water. She didn’t take it. Instead, her eyes searched the room—the wooden beams, the curtained window, a small collection of tools, a bow hanging over the door. Then she looked at him.

He was dark-haired, with features shaped by wind and fire and time. Not young, but not old. His eyes were the color of earth, steady and unreadable. A scar curved down one cheek, vanishing into his collar. His expression did not ask for trust but offered it quietly, as if to say, “You can leave it at the door if you want. No one will take it here.”

She reached for the water. When she drank, he nodded once and turned away. She watched him spoon stew into a bowl, leave it at the table, and return to his corner. Not once did he ask where she’d come from. The silence between them wasn’t empty. It was safe.

By the fifth day, Clara could speak. She whispered her name one night as he was stoking the fire. He didn’t respond, just added a log, waited, then said, “You’ll walk again.” It was the first time he’d spoken since bringing her there. She blinked fast, tears prickling.

“Why did you help me?”

He didn’t answer for a long time. When he finally did, he spoke without looking at her.

“Because someone didn’t.”

The pain in her chest bloomed again, not from the fall, but from memory. Her voice failed her, so she nodded. He saw it and nodded back.

The days grew into a rhythm. Clara learned to move with the crutch he carved for her. She helped peel potatoes, patch the curtains, sweep snow off the porch. He hunted, chopped wood, brought back herbs wrapped in cloth. They never spoke much. But they didn’t need to.

The silence softened. Once she asked, “What’s your name?”

He stirred the stew without looking up. “Ronan.”

It suited him. A name you couldn’t fold, couldn’t ruin.

Clara woke one morning to find a new pair of boots by her bed, lined with fur. Too big, but warm. She cried quietly into her pillow—not because of the gift, but because of how it was left without ceremony, without pride. She never said thank you. She didn’t need to.

That afternoon, she walked a few steps outside. The cold bit her lungs, but she stood there letting the snow fall onto her face, watching the horizon where the cliff still sat in silence. She didn’t ask Ronan to take her back to town. She didn’t want to.

He watched her from the doorway, arms crossed, a blanket around his shoulders. For a moment, she felt seen in a way that didn’t steal anything from her—as if she were not broken, not shamed, not owed, just alive. She looked back toward him, toward the warmth behind the door. She stepped forward. He stepped aside and that was how she came to stay—not because she was taken in, but because she chose to remain.

Smoke from the hearth curled gently upward, blurring the ceiling beams with the scent of pine and ash. Outside, snow slid against the cabin walls. Inside, the silence had changed. No longer a wall between strangers, but a quilt stretched across two souls learning how to breathe again.

Clara sat near the fire, stirring a pot of rabbit stew, one hand wrapped in linen from slicing herbs too clumsily the day before. Her crutch leaned against the table leg. Though her ankle still swelled at sundown, she had begun moving through the cabin without needing Ronan’s arm. He watched her from the doorway, arms folded, his expression unreadable yet softer than when she’d first seen him through swollen eyes.

In those quiet days, she learned more about him through absence than presence. He spoke rarely, but his silences had texture. Some meant he was thinking, others meant he was listening. His movements were exact, his tools always placed where they belonged. He repaired a broken hinge without being asked. Chopped firewood with a rhythm that matched his breath. When he passed her a blanket or spooned broth into her bowl, he never looked directly at her, but she felt the care threaded into every gesture.

She’d come to know his name, Ronan Ghost Hawk, by hearing it in a whisper once when he traded pelts for salt in town. The woman behind the counter had looked him over with a mix of reverence and fear, muttering the name under her breath as if it might burn her tongue. Clara hadn’t asked about it. He hadn’t offered. In return, he never asked for the full story of her fall. He never repeated the questions she heard in her own head each night. He simply gave her space and time. And in doing so, offered something no one else had—respect that did not demand.

Still, words eventually found their way in—over shared stew, over the sound of a lone coyote howling in the dark, over the clatter of snow sliding off the roof.

“I used to sing,” she said one night, voice small, “mostly in the mornings before things changed.”

Ronan had looked up from where he carved a slender wooden bird with a curved beak. “What changed?”

She hesitated. “Everything.”

He nodded once and that was the end of the question.

She began singing again two days later—not for him and not loudly, just to the kettle as she stirred. A hum at first, then the faint shape of a hymn her mother used to hum over rising bread. Her voice cracked at the high notes. She didn’t stop.

At night, she’d lie on the cot and watch shadows from the fire flicker across the log walls. Sometimes, Ronan sat by the fire past midnight, tending to something he wouldn’t name. Once she saw him hold a necklace—worn leather with a small piece of turquoise. He stared at it a long while before tucking it back into a pouch near his heart.

On the eighth night, she asked, “Was it your wife’s?”

He didn’t pretend not to understand. “Yes.”

Clara said nothing, but her fingers pressed against her chest where her own memory throbbed.

The town didn’t stay quiet long. Mrs. Beatrice Elwood, widow and seamstress, had a tongue sharp enough to peel paint. She’d seen Ronan stop by the general store for flour and flint and noted the second pair of boots strapped to his saddle. That was all she needed. By morning, she told half the town, “The cliff girl’s alive, and he’s got her hidden in that ghost cabin past the ridge.”

The whispers spread like snowmelt in spring—soft, inevitable, and cold beneath the surface.

“Why’s he keep her?” “Maybe she’s carrying his half-breed child already.” “Or maybe she bewitched him. Some girls do.”

Even the church folk spoke low and bitter. No one mentioned Sheriff Cain, but his silence fed the tension. He’d been seen drinking more, slapping a bottle off the bar, and muttering about ungrateful brats. No one asked what he meant.

Inside the cabin, the air remained warm, the quiet honest. Clara spent her mornings sitting by the window, watching crows circle the frozen trees. Her ankle healed slowly, her shame faster.

One afternoon, Ronan returned from hunting with a fresh rabbit. “They’re watching the ridge.”

Clara’s jaw tensed. “They think you kidnapped me.”

“They think many things.”

She didn’t ask what he planned to do. He didn’t ask what she wanted. But that night, as they ate by firelight, she said something she’d never dared voice aloud.

“I should have died on that cliff. That’s what they wanted.”

His spoon paused midway to his lips.

“I didn’t,” she continued, “because of snow. And you. But I’m not sure I was meant to come back.”

Ronan set the bowl down gently, his fingers steady. Then, after a long breath, he looked at her—not over her, not past her, directly.

“They threw you away. That doesn’t mean you’re waste.”

Her throat tightened, not from the words, but from how plainly they were spoken. A silence settled between them again. But this time, it wasn’t empty. It was waiting.

Clara reached for her shawl and stood, limping slightly toward the door. Ronan rose, too. Outside, the stars glistened above like frost trapped in black velvet. Snow reflected their light, casting a glow on the porch.

She stood there staring out toward the direction of town. Her voice came quietly.

“I can’t go back to being who I was, and I don’t want to be what they tried to make me.”

Behind her, she heard the soft sound of footsteps on wooden planks. Ronan stood beside her, arms folded against the cold.

“Then don’t.”

She looked up at him, unsure if he meant it so simply, but his eyes said he did.

The next morning, she rose early and cut her hair—not out of rage, not out of shame, but as a way of shedding something. She tied the long strands into a bundle and placed it in the fire. Ronan said nothing, only added another log.

Later that day, she stitched a new hem into her dress, making it shorter, more practical. Then, she walked outside with no cloak, letting the cold bite her arms. She didn’t flinch.

In town, Mrs. Elwood swore she saw smoke rise from the ridge and said it looked like something had been released into the sky, and Sheriff Cain began sharpening his knife.

The sky wore its heaviest gray that morning, low, brooding, full of promises it intended to keep. Smoke curled from the chimney of the cabin in the woods, not with cheer, but necessity. The cold was no longer a visitor. It had unpacked its bags.

Inside, Clara stirred a pot of beans slowly, her mind elsewhere. Her ankle no longer swelled, and her hands no longer trembled when she braided her hair. She had begun speaking more and even laughing once, though it surprised her as much as him. Still, some part of her stayed braced, like she knew the quiet could not last.

Ronan felt it, too. He said little, but he sharpened his knives longer each night, checked the door latch twice, and took to riding out farther when gathering wood, his eyes scanning the treeline instead of the trail. He didn’t say why. He didn’t have to.

It was late afternoon when the first bootprints were heard—not one pair, but several, crunching hard in the snow. Ronan stood at the window, hand resting on the windowsill, jaw tight.

“They’re here,” he said.

Clara put down the ladle and wiped her hands on her skirt. She didn’t ask who. She already knew.

When the knock came, it wasn’t a knock at all. It was a pounding, angry and entitled. Ronan didn’t open the door. He stepped outside instead.

There were six men, all mounted, all armed. At their center was Sheriff Luther Cain, still wearing his badge, though everyone could see it no longer shined. His face was ruddy with drink, his coat trimmed with fur as if to remind others of who he thought he was.

“Well, well,” Cain drawled, dismounting with a grunt. “Look at you, living like a savage king.”

Ronan said nothing. He simply stood, arms at his sides, steady.

Clara watched from behind the curtain. Her breath caught when Cain’s eyes drifted toward the door.

“Now, Ghost Hawk,” Cain continued, spitting the name like a burr in his teeth. “I’ve come out of decency. I could have sent the boys ahead, no talk. But I figured I’d ask nice first. That girl’s mine. She’s been taken.”

“You threw her,” Ronan replied, voice low.

Cain’s face twitched. One of his men shifted uncomfortably in the saddle.

“She ran,” Cain said louder. “And even if she hadn’t, this ain’t your fight. It’s town business.”

Ronan stepped forward once. “She’s not property.”

Cain smiled cold. “No, she’s a mistake. One I intend to correct.”

Clara opened the door then, stepping out with no coat, no fear. Her face was pale from winter but calm. The wind blew her hair back, and even from a distance, she looked taller than she had before.

“You don’t get to talk about me like I’m not here,” she said.

Cain’s head turned sharp and quick. His eyes narrowed.

“Girl,” he muttered, “you’re lucky I don’t bring you back in chains.”

“You already did that once,” she answered. “I still have the scars.”

There was a long silence—the kind that hangs between thunder and lightning.

Ronan stepped between them, not with violence, but with purpose.

Cain bristled. “You want blood?”

Ronan asked, “You’ll bleed first.”

Cain’s men looked at one another. Some of them had wives. Some had daughters. And Clara, standing there, proud and unbroken, was no ghost. She was human, more alive than Cain’s rage could shadow.

Still, Cain drew his revolver. It happened fast. One of his men reached for his own gun. Ronan stepped forward, arm lifted to shield Clara. The shot rang out—not from Cain, but from Ronan’s shoulder. Blood bloomed dark against the snow as the bullet ripped through flesh.

Clara cried out and reached for him, pulling him back, her fingers slipping on his coat. Cain raised his gun again until he heard the sound behind him. Click. The unmistakable sound of a deputy cocking his rifle, pointed not at the cabin, but at Cain. It was the youngest of them—the same who had looked away on the cliff.

“Enough,” the boy said.

Cain turned, eyes wide. “You turning on me?”

“I saw what you did,” the boy said. “I helped. I’m not helping again.”

Another deputy lowered his weapon. And then another. The silence returned, but this time it belonged to Clara. She stepped forward past Ronan, her hand shaking but her voice clear.

“You don’t get to finish what you started. Not today.”

Cain stared at her. And in that moment, the sheriff, who’d ruled with threats and smirks, looked suddenly small. His power didn’t crack—it vanished. He holstered his gun with shaking hands. Without a word, he mounted his horse. The others followed, the youngest nodding once to Clara before turning away.

Only the snow remained, falling gently over blood, over footprints, over the smoke that curled once again from the chimney.

Clara helped Ronan inside, tore strips of her apron to wrap his shoulder, her fingers moving with precision and grace. He didn’t cry out. He watched her instead as if seeing her anew.

“You didn’t have to step out,” he whispered.

“I did,” she said, “so I could walk back in.”

Night fell slow. Stars blinked through the gray, and inside the cabin, firelight danced again. Clara sat by Ronan’s side as he slept, his breath shallow but strong. She didn’t cry. Not yet. She held his hand and watched the flames. Behind her, the world had shifted. And somewhere in town, the sheriff’s name was being spoken, not with fear, but with a question. And the girl they thought broken now stood in memory like fire on snow.

The snow did not melt that spring—not all of it. Beneath the trees near the ridge, the drifts lingered, stubborn and quiet, holding perhaps the memory of blood and footfalls, the breath of a girl who had once been thrown, and the man who caught her without lifting a hand.

Inside the cabin, light filtered through the curtains like soft gold. Ronan’s wound had healed slowly, the scar a pale crescent beneath his collarbone. He moved with less ease now, but never once did he complain. Clara noticed he began writing small things in a notebook, short lines in a language she didn’t understand with careful brush strokes. He didn’t say what they meant. She didn’t ask. What mattered was that he’d started keeping record of the days.

She had changed, too. The tremble in her voice had vanished. Her hair was shorter, her step lighter. She no longer asked permission to do things—not because she’d grown defiant, but because she no longer believed she needed to apologize for existing.

When she walked into town with Ronan for the first time, no one spoke. But they saw. Mrs. Elwood dropped her spool of thread. Reverend Hart turned his gaze to the street lamps. The butcher’s wife nudged her son not to stare. Clara held her head high. They didn’t go for supplies. They went for truth.

Sheriff Cain had left town the week after the standoff. No badge, no goodbye. Some said he headed west. Others said he drank himself into dust. Clara didn’t care, which was true. What mattered was that the fear he’d planted no longer bloomed. Still, even weeds leave seeds.

At the town hall, Ronan stood quietly behind Clara while she stepped to the ledger and signed her name under a new column: residing beyond township boundary, under her own accord. No permission, no property listed, just her name—Clara Rose McKinley. And beside it, without ceremony, Ronan signed his. Not marriage, not ownership, just names together.

When they left, a few townsfolk watched from windows, eyes flickering between shame and awe. But no one stopped them. No one dared.

Back at the cabin, Ronan replaced the broken hinge on the door with a brass one Clara had chosen from the general store. She smiled as it clicked into place—a sound more permanent than vows.

In the evenings, they planted root vegetables behind the cabin. Clara dug while Ronan hoed rows, both moving slowly, steadily. Her laughter came easier now. His shoulders didn’t tense when she touched his arm. He carved her a new crutch, smaller and lighter, though she needed it less each day.

Once under a purple dusk sky, she said, “You never asked me what I wanted.”

He looked at her and replied, “You didn’t need to want. You needed to heal.”

She nodded then. “But now I do.”

He raised an eyebrow, silent.

She gestured to the ridge in the distance. “I want to go back.”

So they went. It took the better part of a day to reach the top. Clara’s limp slowed them, but she didn’t falter. Ronan walked beside her, saying nothing as the wind rose and the trees grew sparse. The path curved just as it had that day, though now the snow was softer, cleaner. No blood marked it. No men waited.

When they reached the cliff, she stood at its edge and looked down. The rocks below still crouched like teeth. The pine that caught her fall remained, bent but unbroken. For a long time, she said nothing, just breathed. Then she pulled from her satchel a small bundle of cloth tied with string—her old hair. She laid it gently at the edge of the cliff, weighing it down with a single stone.

“I leave her here,” she whispered—the girl who begged, the girl they tossed.

The wind took the ends of her words and carried them away.

Ronan stepped forward, offering her his hand. She didn’t take it at first. She stood steady, facing the place that had nearly ended her. Then she turned, took his hand, and walked away without looking back.

Later that night, they sat by the fire, a blanket around their shoulders. The cabin had become a home, not just shelter. It held the shape of their days, the rhythm of shared silences. He leaned in close.

“You still sing in the mornings.”

She smiled. “You still pretend not to listen.”

Outside, snow began falling again—not heavy, just enough to catch the moonlight. It dusted the porch, kissed the firewood, softened the scars in the trail.

They did not speak of marriage. They did not speak of what the town thought or would think. Their love was not made of grand promises or church bells. It lived in the way he refilled her tea before she asked, the way she laid her hand on his when dreams turned cruel in sleep.

Months passed. Then came the spring thunder, brief, warm, alive with color. The garden they’d planted began to sprout. Clara laughed when the carrots came up crooked. Ronan taught her to braid onions to hang from the rafters. Sometimes they walked the ridge again, not out of memory, but to measure how far they’d come.

The town forgot her name or rewrote it. Stories changed, twisted, grew gentler in the mouths of the afraid. She left town by choice, they said. Married an Indian, I think, lives out near the ridge. They never said the word thrown, never said tried to kill, but the snow remembered. Every spring, just before the thaw, one spot near the cliff stayed white longer than the rest. Travelers said it looked like the imprint of a woman’s body lying still. Others said they heard singing.

Clara never corrected them.

One evening, many years later, she sat by the fire with a child on her lap—hers or not, didn’t matter. The child looked up and asked, “Did it really happen? Did they really throw you?”

She smiled—not bitterly, not sadly, just softly, like someone who’d grown tall enough to see above the storm.

“They thought they buried me,” she said. “But I was seed.”

Then she tucked the child into bed, kissed their brow, and returned to the porch where Ronan waited—older now, but still steady. And together they watched the snow fall one last time, silent, soft, and holy, like it remembered every step they had taken, every step that had brought her back to herself.

.

play video: