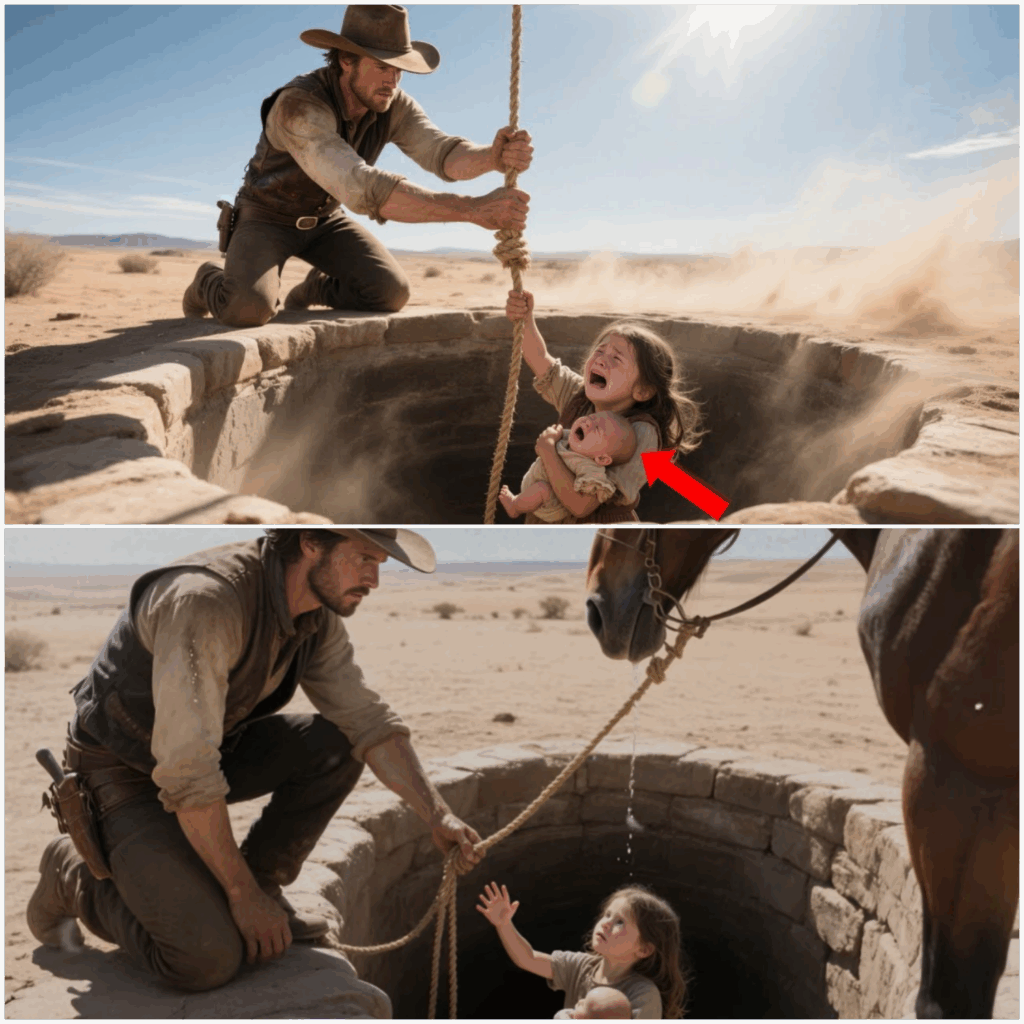

He Came For Water, But Found 2 Children In a Well, And Cowboy Who Pulled Them Out Was Never the Same

.

.

He Came For Water, But Found Two Children In a Well—And The Cowboy Who Pulled Them Out Was Never The Same

The desert wore its silence like a heavy shroud. At noon, the sun pressed down until the air itself shimmered and the wind carried dust in restless swirls across the barren flats. Boon Mallister tugged the reins of his weary horse and scanned the horizon. The animal’s ribs showed beneath its hide, and the canteen at Boon’s hip was little more than an empty rattle. He had been riding since dawn, chasing the faint memory of a well marked on an old trail map, his throat burning with the taste of dust.

When he saw the ring of stones rising from the earth ahead, he felt a small, sharp tug of hope. Water meant survival. The well lay sunken into the ground like a wound in the earth, its circle of stones weathered and broken. Boon dropped the reins and stepped closer, the ground dry and crumbling beneath his boots. He braced himself on the rim and leaned over. At first, he heard nothing but his own breath echoing in the hollow below. Then, faint and trembling, a sound drifted upward—not wind, not water—a cry, thin and frightened, human.

Boon’s hand tightened against the stones. He crouched low, squinting into the shadowed depths. Two shapes shifted in the dark—a child’s arms wrapped tight around something smaller. The older one lifted her face toward the rim, eyes wide, cheeks streaked with dirt, lips cracked and trembling. Boon drew back as if struck, his chest tightening. He had come for water. Instead, he had found two children waiting for death.

“Hold on,” he called down, his voice raw, more command than comfort. The girl flinched but did not loosen her grip on the baby in her arms. Boon searched the stones for a bucket, a rope, anything. Only a frayed length of hemp trailed down into the dark. He seized it, tested its strength with a hard tug. It held, though each fiber groaned as if weary of carrying weight. He looped the rope around his wrist, steadying himself.

“I’ll pull you up,” he said, more gently now. The girl stared, uncertain, her small shoulders trembling. Dust swirled between them, carried by the hot wind, and Boon felt the press of time, the urgency of thirst and heat. The girl’s lips parted. A rasp of a whisper reached him: “Don’t let go.” Boon swallowed hard. “I won’t.” Her arms shifted as she wrapped the rope around herself and the baby, who whimpered weakly against her chest.

Boon leaned back with all his weight and began to haul them upward, hand over hand, muscles burning. Stones bit into his knees as he braced against the well’s rim, sweat sliding down his temple. Each pull lifted them an inch closer to the light. The girl’s eyes never left his—wide, with a desperate trust she had no choice but to give. Boon’s breath came ragged, but he pulled again and again until at last her small hands gripped the edge of the stones. With a final heave, he caught her beneath the arms and lifted both children over the rim, collapsing back against the sand with their weight against him.

For a long moment, none of them moved. The baby whimpered, thin and frail, and the girl clutched him tighter, burying her face in his dust-matted hair. Boon steadied them with his hands, careful as though holding something that might break. His chest rose and fell, sweat and dust mingling on his skin, heart pounding with more than effort.

The girl pulled back just enough to study him. Her face was smudged, her dress torn and hanging loose from one shoulder. She could not have been more than six, yet her gaze held the fierce, suspicious fire of someone who had already learned too much of cruelty. Boon knew that look. He had worn it himself once, when the world had offered no safe place to rest.

“What’s your name?” he asked quietly. She pressed her lips together, eyes darting toward the empty horizon as though expecting someone else to come for her. Boon waited, his silence patient. At last, she whispered, “Lydia.” He nodded. “And him?” Her arms tightened around the infant. “Caleb.” The baby stirred weakly, too tired for a cry, his cheeks hollow, eyes glazed with thirst.

Boon reached for the canteen at his side, shook it, and grimaced at the hollow rattle. “I’ll find you water,” he said, more to himself than to them. The girl’s small chin lifted, suspicion flickering. “Why?” Boon hesitated, caught off guard by the bluntness of the question. Why, indeed? He was a man who had once turned away when others needed him most. A man whose shame lingered like a scar beneath the surface of every quiet night. Yet, as he looked at the children, one clinging, one too weak to resist, he felt something break loose inside him. A silence that had lived in him for years shifted like earth after rain.

“Because nobody else did,” he said finally. Her eyes lingered on him, testing the shape of his words, the truth in them. At last, she lowered her gaze, pressing her cheek against Caleb’s hair.

Boon eased himself upright, scanning the horizon. Not a soul in sight. Only the endless desert, the pale light of noon, the dust devils twisting in the distance. He lifted Lydia with one arm, the baby in the crook of the other. The weight of them was fragile but binding, as though the rope had tied more than their bodies to him. His horse snorted softly, shifting in the heat, as if uneasy with the silence that stretched over the flats.

Boon carried the children a few steps before setting them gently in the shade of the well’s crumbling stones. He tore a strip from his sleeve, dipped it into the last drops of water from his canteen, and pressed it against Caleb’s lips. The infant stirred, sucking weakly. Boon felt the smallest flicker of relief, though the dryness of the land mocked it. Lydia watched him, her gaze never wavering, equal parts fear and fragile hope.

Boon avoided her eyes, focusing on the horizon where the faint outline of Dry Creek shimmered in the distance. The town meant questions, judgments. Boon had not been welcomed there for some time, and he carried the weight of old mistakes like shadows at his back. Yet he could not leave the children here, waiting for death.

When he met Lydia’s eyes again, she spoke so softly he almost missed it. “They left us down there.” The words fell heavy between them, as if the desert itself had gone still to listen. Boon crouched low, his hands steadying her shoulder. “Who?” he asked. Her gaze flickered upward to the wide and merciless sky. Her lips trembled as she whispered, “Everyone.”

The silence after that was deeper than any well.

The town of Dry Creek shimmered in the heat like a mirage, its crooked buildings leaning into the wind as though they too longed for escape. Boon Mallister rode slowly through the dust with Lydia perched in front of him, Caleb cradled in one arm against his chest. The horse’s hooves struck hollow on the hard-packed road, each step sending up a small cloud that clung to sweat and skin. Heads turned as they entered, doors creaked open, curtains shifted. Dry Creek was a place where silence held judgment, and every man or woman had eyes sharp enough to cut.

Lydia shrank against him, her thin fingers clutching his vest, eyes darting from one face to the next. Caleb whimpered, too weak for more than a thin cry. Boon kept his jaw set, gaze steady ahead, though the weight of the stares pressed against his shoulders heavier than the children. He had known this town’s suspicion before. It had grown like weeds in the cracks of his mistakes. But today, with two fragile lives depending on him, every whisper felt sharper, more dangerous.

By the time Boon reined his horse near the trough outside the general store, a small knot of townsfolk had gathered. An old man with a tobacco-stained beard spat into the dust. “What’s he done now? Dragging in half-dead young’uns.” A woman fanned herself with a bonnet, lips pursed. “Found ’em or stole ’em—makes no difference. Trouble clings to him like flies.”

Boon swung down from the saddle, his movements deliberate, quiet. He lifted Lydia down, her feet touching the earth unsteady, then drew Caleb close against his chest. The crowd edged nearer, circling like buzzards drawn by curiosity and suspicion. Boon said nothing. He had learned long ago that words in Dry Creek were twisted faster than wire.

Lydia pressed into his side, her chin lifted in defiance, despite the tremble in her lips. Boon saw it, that stubborn flame. It reminded him of himself when he had still believed he could fight the world alone. He laid a steadying hand on her shoulder.

The sheriff arrived with the measured gait of a man who believed every street belonged to him. Broad-shouldered, gray-eyed, his star glinted in the unforgiving sun. He looked at Boon, then at the children, his jaw tightening with something between suspicion and weariness.

“Mallister,” he said, voice flat. “What have you got there?”

Boon’s voice came low. “Evenin’. Children. Found in the well out past Ridge Flats.” A murmur swept through the gathered crowd.

The sheriff’s brows furrowed. “That old well’s near caved in. Nobody rides that far without reason. What were you doing there?”

Boon met his gaze without flinching. “Looking for water.”

The sheriff’s eyes lingered on him, weighing the truth against Boon’s reputation. At last, he grunted. “Town needs answers. Whose brats are they? Can’t just drag in strays and expect it to sit quiet.”

The crowd pressed closer, their whispers now sharp as stones thrown. “He’s hiding something, probably his own. Poor things won’t last with him.”

Boon stood motionless, the weight of Caleb against his chest anchoring him. The warmth of Lydia’s small body pressed against his side, reminding him that silence would not shield them forever.

It was then that Evelyn Hart stepped forward, breaking the circle. A widow wrapped in a plain gray dress, her dark hair pinned back, eyes steady though shadowed with her own history of judgment. She carried a basket, its contents half forgotten, as she paused before Boon and the children. The crowd’s whispers shifted, some sharp with scorn, others softened with curiosity. Evelyn was a woman they pitied, gossiped about, but seldom approached.

Her gaze lingered on Caleb, then rose to Lydia’s weary eyes. Without a word, she drew a small flask from her basket, knelt, and offered it to the girl. Lydia hesitated, glancing at Boon. He gave the faintest nod. Lydia took the flask, tilting it carefully to Caleb’s lips. The baby sucked weakly, and Evelyn’s shoulders loosened as though she had been holding her breath.

The sheriff cleared his throat. “Mrs. Hart, this ain’t your concern.”

Her voice was quiet, but carried. “Children are everyone’s concern, sheriff. Or have we forgotten?”

A stillness followed, the kind that left men shifting uncomfortably in their boots. Boon felt something stir in his chest. Not gratitude spoken, but the recognition of courage where the town least expected it. Evelyn rose, her eyes meeting Boon’s briefly, and in that fleeting moment, something unspoken passed between them. Not trust, not yet, but the beginning of it.

The sheriff’s face hardened. “We can’t have him stay here without knowing where they come from. Might belong to someone, might not. Could send ’em on the orphan train when it passes next week.”

The words sliced through Boon. The thought of Lydia and Caleb swallowed by some far-off rail car, faces pressed to glass as they vanished into the world’s indifference, rooted him to the dust. Lydia’s small hand found his, gripping tight. She didn’t speak, but her eyes begged in silence.

Boon straightened, his voice low but firm. “They’re not leaving with that train.”

The sheriff’s eyes narrowed. “You saying they’re yours to keep?”

Boon met his stare, the sun burning down on the space between them. “I’m saying I pulled them out of that hole, and I won’t let anyone throw them back in.”

The crowd shifted uneasily, whispers rising like insects in summer heat. Some looked away, unwilling to meet the weight of Boon’s words. Others scowled, their doubt sharpening. Evelyn’s gaze lingered on Boon, steady as though measuring the cost of his defiance.

The sheriff gave a short, cold laugh. “Big words for a man who couldn’t keep his own life straight. You think rescuing strays will make this town forget?”

Boon said nothing. His silence was heavier than any answer. And in that silence, the children clung closer, the dust swirling around them like judgment made flesh.

The sheriff stepped back, spitting into the dirt. “We’ll see what the town decides. Until then, keep ’em out of trouble.”

The crowd dispersed slowly, whispers trailing behind them like shadows. Evelyn lingered only long enough to press a small loaf of bread into Lydia’s hands before she turned away, her figure swallowed by the shifting heat.

Boon lifted Caleb higher against his chest, reached for Lydia’s hand, and led them toward the edge of town. His horse trailed behind, tired and dust-caked. The stares followed them still, but Boon kept his gaze fixed on the open road. As they left the last building behind, Lydia looked up at him, her voice small but piercing. “They’ll take us, won’t they?”

Boon’s hand tightened around hers. He searched for words, but found only silence, the kind that weighed like an unspoken vow. The horizon shimmered ahead, endless and uncertain. Boon kept walking, his shadow stretching long beside the children, while behind them the town of Dry Creek whispered like a jury not yet finished with its verdict.

Don’s ranch lay at the edge of nowhere, a place half-built and half forgotten. The fences sagged, the barn leaned like an old drunk against the wind, and the house carried the smell of dust and wood that had not felt polish in years. Yet, as Boon pushed open the door with Caleb in his arms and Lydia trailing close behind, the air shifted. What had been silence became burdened with small breaths, soft footsteps, the sudden weight of fragile life beneath his roof.

Lydia stood just inside the doorway, her arms folded tightly around herself, her eyes scanning the barren room—a single table scarred by knives and weather, a hearth blackened from fire long gone cold. She seemed to measure the place as if deciding whether it could keep her safe. Boon watched her with a strange unease, aware of how empty the room had looked until she stepped into it.

He laid Caleb gently in a worn cradle he had once built with hands that had expected to fill it with his own bloodline. It had remained empty for years, tucked against the wall like a relic of failure. Now, with the infant curled inside, the wood seemed to breathe again. Boon looked away quickly as if ashamed of the stir in his chest.

Lydia noticed. She moved to the cradle, laying a protective hand on Caleb’s small chest. Her chin lifted in silent defiance, as if daring Boon to prove himself unworthy of the trust necessity had forced upon her. Boon crouched beside her, his voice low. “He’ll need milk. I’ll ask in town tomorrow.”

Her eyes narrowed. “They don’t want us there.”

Boon held her gaze. “They don’t get to decide what you need.”

Something in her expression shifted, faint, like a crack in a wall that had stood too long. She did not answer, but she stayed close, watching him as he stirred the cold hearth back to life with careful strikes of flint. Sparks caught, flames rose, and the shadows in the room softened.

The days that followed moved like wind over dry grass, subtle but never still. Lydia tested him with small rebellions, refusing food until hunger wore her down, watching him with eyes sharp as knives whenever he came near the cradle, whispering promises to Caleb in the dark that she would take him away if Boon proved cruel. Boon never argued, never raised his voice. Instead, he answered with quiet gestures—mending the tear in her dress with clumsy stitches, setting an extra blanket near her spot by the hearth without a word, carving a small wooden figure by lamplight and leaving it where her hand would find it come morning.

Slowly, almost unwillingly, Lydia began to watch him differently. Not with trust, not yet, but with a weary patience, as though testing whether his silence might be safer than the world’s noise. Caleb, weaker still, began to stir more, his cries thin but steady. Boon would lift him against his broad chest, swaying in slow, unpracticed rhythms until the baby quieted. More than once, Lydia awoke to find Boon asleep upright in the chair, Caleb draped across him like a fragile burden he dared not put down.

Evelyn Hart visited after three days, her figure carrying the hush of someone who had grown used to being unwelcome. She came with milk and bread, her eyes sweeping over the broken fences and roof patched with tin. She did not linger on the ranch’s failings, nor on Boon’s. Instead, she placed the jug on the table and met Lydia’s weary eyes with a softness that seemed to ease the girl’s breath. Caleb fed that day with more strength than before, his tiny hands curling around Evelyn’s fingers.

When Evelyn left, Boon walked her to the porch. The sun was falling low, setting the horizon in firelight. She paused, her hands folded at her waist. “The sheriff’s been asking questions,” she said quietly. “He thinks the children will bring trouble.”

Boon’s jaw tightened. “The trouble was leaving them down there.”

Her eyes searched his, weighing his words as though testing their strength. “And what of the trouble that comes after?”

He had no answer. Evelyn left him with that silence, her figure fading down the dirt road until dusk swallowed her whole.

That night, Boon sat outside the cabin, the desert stretching around him like an endless trial. Lydia stepped onto the porch, her bare feet light as dust. She carried Caleb, wrapped in the extra blanket Boon had set out. For a moment, she said nothing, only stood watching him as if trying to read what lived in the quiet of his face. Then, with a voice that quivered but did not break, she asked, “Are you going to throw us back when it gets hard?”

The question struck like a blade sliding between old scars. Boon looked at her, at the fierce set of her jaw, the way she clutched Caleb as if the whole world was trying to take him. Shame rose in him, thick and bitter, for all the times in his life he had walked away when things turned hard. He wanted to say no, wanted the word to fall from his lips with the certainty she craved. But the truth caught in his throat. He was not yet the man who could promise it.

Lydia studied him, and for a moment the fire in her eyes flickered toward despair. She turned as if to retreat into the cabin. Boon rose quickly, his hand brushing her shoulder, light but steady. “I don’t know what I am,” he said, voice rough. “But I won’t leave you in the dark.”

Her gaze lingered on him, searching for cracks in the promise. At last, she gave a short nod, small but binding, and returned inside. Boon stood on the porch long after, the stars spreading overhead like silent witnesses.

The next morning, whispers began to reach him from Dry Creek. A ranch hand passing by muttered of townsfolk, saying Boon had stolen the children, that no good could come of him keeping them. By week’s end, the sheriff himself rode out, reins tight in his fists, a look in his eye that spoke of unfinished judgment.

He dismounted at Boon’s fence, boots striking the dust with purpose. Lydia stood at the doorway, clutching Caleb, her eyes fixed on Boon. The sheriff’s shadow stretched long between them. Boon stepped forward, every muscle taut, his voice steady, though the air seemed to still around them. “If you’ve come to take them,” Boon said, “you’d best be ready to climb down that well yourself.”

The sheriff’s eyes narrowed, lips curving into a smile that held no warmth. “You always did mistake defiance for salvation, Mallister. But this time, the town’s watching.” And with that, the line between past failures and present defiance was drawn sharp in the dust, daring Boon to cross it.

The sheriff’s words lingered in the dust, bitter as iron. Boon stood firm at the edge of his worn fence, the sagging posts creaking in the hot wind. Behind him, Lydia clutched Caleb, her small body stiff with fear, but her chin lifted in stubborn defiance. Evelyn Hart had come too, carrying a basket she had not yet set down, her presence quiet, but unwavering. The three of them formed a fragile line, bound not by law, but by something older and more stubborn—need, and the thin thread of hope.

The sheriff let silence stretch, letting the weight of the town’s whispers do his work. Men had gathered behind him, townsfolk drawn like moths to the smoke of conflict. Their boots stamped the dust, their eyes sharp, some uncertain, others eager to see Boon brought low. Boon felt their judgment settle heavy on his shoulders, but he kept his gaze fixed on the sheriff. He would not bow to them. Not this time.

“You’ve no claim,” the sheriff said finally, his voice cut flat across the air. “The law won’t let strays be raised by a man who can’t even keep himself steady. Give them up. Let the town decide what’s proper.”

Boon’s jaw tightened. For years, he had carried silence like a shield, swallowing his shame, avoiding the eyes of those who had written him off as a failure. But now Lydia’s small hand gripped the back of his shirt, and Caleb’s thin cry rose against the wide sky, and something in Boon broke free. His voice, when it came, was rough, but steady.

“I’ve made mistakes,” he said loud enough for the crowd to hear. “I failed more than once, and I’ve turned away when I should have stood firm. But I won’t turn from them.” He gestured to the children, his hand trembling, not with fear, but with conviction. “I pulled them out of a hole no one else looked into. That makes me theirs, and them mine. You can write your law against me, sheriff, but you’ll have to carve it into my skin before I let go.”

Murmurs rippled through the crowd, shifting uneasily. Some frowned, some looked away. Evelyn’s eyes shone steady on Boon, though her hands gripped her basket until the wood creaked. Lydia pressed closer, her small face lifted toward Boon as if his words were the rope holding her above the dark again.

The sheriff’s smile was thin, mocking. “Big words, but words don’t feed bellies, Mallister. Words don’t make you a father.”

It was then Lydia’s voice rose, clear and sharp as a bell. “He pulled us out.” The crowd stilled. Her voice trembled, but she did not lower her chin. “Nobody else did. Everybody else left us down there. But he came.”

The words fell heavy, more powerful than any law because they rang with the raw truth only a child could speak. The sheriff shifted, his confidence faltering. The crowd’s whispers softened, some muttering in shame, others in reluctant agreement. A few turned away entirely, unable to meet the girl’s fierce, dirt-streaked gaze.

Boon felt the moment like a door swinging open in his chest. He had not asked for her defense, but hearing it, he realized it was not only him pulling Lydia out of darkness. She had done the same for him, dragging him into the light of his own resolve.

Evelyn stepped forward then, her voice quiet but cutting. “This town spends so much time judging what’s proper, it’s forgotten what’s human. Children don’t need a law. They need arms that will not drop them.” Her gaze swept the crowd, and one by one, eyes faltered.

The sheriff scowled, but the force had gone from him. He spat into the dust, muttered something Boon could not catch, and turned back toward his horse. The townsfolk scattered slowly, the heat dispersing them like shadows under the noon sun. Soon, only the sheriff’s retreating figure remained, his star glinting once before it vanished into the haze.

Boon stood motionless, chest rising with a slow, heavy breath. Lydia still clung to his shirt, her grip fierce. Caleb’s cries softened, soothed by the rhythm of Evelyn’s gentle hand patting his back. The silence that followed was different than before—not empty, but full, heavy with what had just been won.

At last, Boon turned, his eyes meeting Evelyn’s. No words passed between them, but something settled in the space between their gazes. Not a promise, not yet, but the beginning of one. He looked down at Lydia, who met his stare with eyes too old for her years. She did not ask again if he would throw them back. She seemed to know the answer now.

The sun began to fall, the desert horizon a wash in the glow of fire and blood. Boon lifted Caleb into the cradle of his arms, then reached for Lydia’s hand. Evelyn walked beside them as they turned toward the cabin. Their shadows stretched long across the dust, three threads bound together, fragile but unbroken.

When they reached the porch, Boon paused. The well’s rope still lay coiled on his saddle, frayed and rough—the very rope that had carried Lydia and Caleb back to the world of the living. He held it for a long moment, the fibers biting his skin before hanging it by the door. A reminder, a burden, a vow.

As night crept over the land, Boon sat by the fire with Caleb in his arms, Lydia curled against his side, and Evelyn quiet nearby. The flames painted their faces gold, shadows shifting like memories on the walls. Boon’s eyes burned not with shame, but with something steadier, something almost like peace. He had been a man lost, weighed down by the emptiness of his own failures. But the children had tied him to the living world again, pulling him out of the dark well he had built within himself.

He spoke only once, his voice low, more to the fire than to them. “Sometimes a man doesn’t choose who he belongs to. Sometimes the choosing’s done for him.”

Lydia’s hand found his, small fingers twining with calloused ones. Evelyn looked toward him then, her face soft in the firelight, and Boon felt the weight of the world shift ever so slightly toward grace.

Outside, the desert wind carried dust across the wide flats, erasing the tracks of men and horses alike. But inside the cabin, three lives stitched themselves together in silence, fragile and uncertain, yet unyielding. The sheriff’s threats, the town’s whispers—they would return. Trouble never failed to ride again. But Boon Mallister no longer carried his shame alone, and that truth would not be taken back.

The fire crackled, the baby sighed, the girl’s eyes drifted shut. Boon sat steady, his heart thudding with a quiet vow. He would not let them fall again. Not into the earth, not into the dark, not while he still had breath. And for the first time in years, Boon believed himself.

.

play video: