He lived (and died) through every Backpacker’s WORST Nightmare…

.

.

.

He Lived (and Died) Through Every Backpacker’s Worst Nightmare

1. Prologue: Snowbound

In May 2016, a young hiker named Ian Cromby trudged through deep snow in northern New Mexico, following the Continental Divide Trail (CDT). He was early in the season, his boots sinking into drifts left by a stubborn winter. But Ian was about to make a discovery that would chill him to the core—and finally solve a mystery that had haunted the region since the previous year.

He stumbled into a remote US Forest Service campground, seeking shelter and perhaps the small luxury of a vault toilet. But what he found scratched into the bathroom door sent a shiver up his spine:

Dead CDT hiker inside. Call cops. Not a joke.

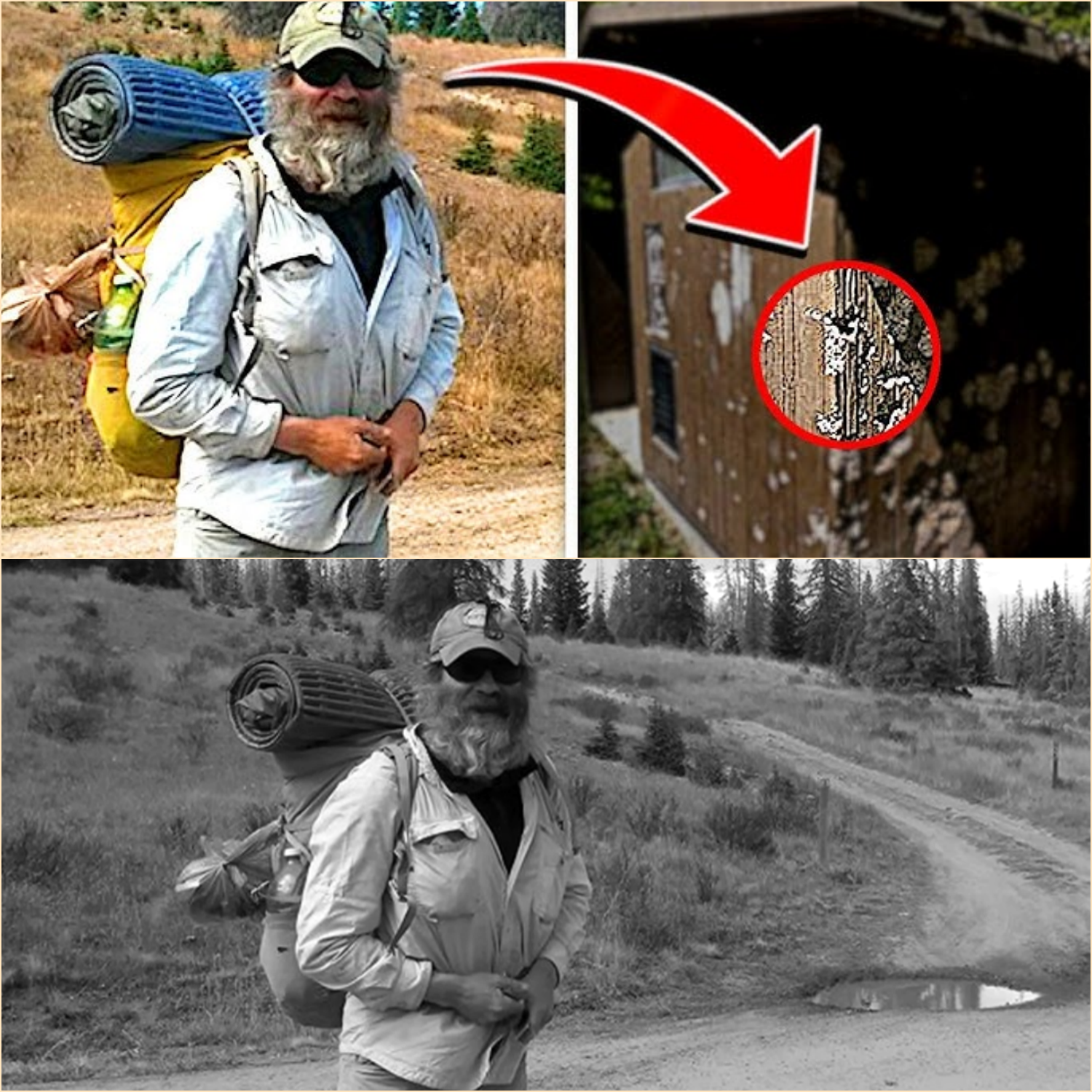

Inside lay the body of Steven Olshansky, known on the trail as “Otter.” This is the story of how one of the most accomplished backpackers in history lived—and died—through every hiker’s worst nightmare.

2. The Legend of Otter

Steven “Otter” Olshansky was no novice. At 59, he was a legend among hikers—a “Triple Crowner” who had completed the Appalachian Trail, Pacific Crest Trail, and the CDT, not just once, but multiple times. He was a fixture in the hiking community, known for his endurance, experience, and infectious spirit.

In the fall of 2015, Otter set out southbound on the CDT, a 3,000-mile trek from Canada to Mexico, traversing the spine of the Rocky Mountains. He knew the risks of hiking late in the season—by November, snowstorms could blanket the high country, turning familiar trails into lethal traps.

Otter spent a few days with trail angels Ben and Jill Widing in Chama, New Mexico, discussing the impending storms and testing his winter gear. He knew the weather could turn, but he was determined to finish.

On November 14, 2015, Otter was dropped off at Cumbres Pass, Colorado. It would be the last time anyone saw him alive.

3. Into the Storm

Otter kept a journal and recorded videos for YouTube, chronicling his journey. But as soon as he left Cumbres Pass, he realized he was in serious trouble.

The snow was deeper than expected—waist-high in places. His body was weak, and he felt faint whenever he stood. He found a patch of ground and pitched his tent, hoping to ride out the storm.

The snow piled up for days. When it finally stopped, Otter tried to backtrack to Cumbres Pass, but he was too weak to make it even a mile. He returned to his campsite, knowing he was stuck. He had no GPS device, no cell signal, and no way to call for help.

He used the last of his phone battery to record a message:

“I’m in big trouble. I’m snowbound. I tried to hike out yesterday. It’s about 10 to 12 miles back on the road and I can’t make it.”

Otter owned up to his mistake:

“I made a huge mistake. I should have turned back or never come out here this time of year. I really rolled the dice and I lost.”

He hoped that Ben Widing, who knew his itinerary, would sound the alarm if he didn’t check in within ten days. But ten days came and went before anyone realized Otter was missing.

4. The Wait

Otter spelled out “HELP” in the snow, hoping a plane would spot it. He fashioned homemade snowshoes from branches and huddled in his tent as another storm rolled in. He waited until December 1, then decided to try for Logan’s Campground, three miles down Forest Service Road 87—a place he’d slept before.

He wrote in his journal:

“Took a lot of courage to pack up that day. I hiked 200 yards, bent over from total exhaustion in the waist-deep snow. I looked back to the place where I had spent 17 days—safe, but a coffin. A few steps, bent over—it took all day. I could not go one step further and was about to just sleep in the snow. Then I looked to my left and saw the bathroom. I squeezed inside the ice box, shivering, got into my sleeping bag, cranked up the wood stove for a hot drink.”

Meanwhile, the search for Otter was finally beginning. His next planned stop was Ghost Ranch, where a resupply box waited. But he never arrived.

5. The Search and the Sighting

On December 10, aerial searches covered 300 square miles of Carson National Forest. The conditions were brutal—snow obscured everything. That same day, a ranger in Grants, New Mexico, thought he saw Otter at a forest service station. The man asked for directions to the post office, but Otter was familiar with Grants and wouldn’t have needed directions. The sighting was likely a case of mistaken identity.

Still, the report caused the official search to lose momentum, much to the horror of Otter’s friends and family.

On December 10, Otter tried to signal for help again. He burned down a wooden shed at the campground, hoping the smoke would attract attention. He used pieces of the metal roof to create makeshift skis and tried to ski away, but didn’t make it far.

He wrote:

“Just as I was at the end of the entrance road, along comes a search and rescue plane directly above me. I was out in the open. They flew over the campground and might have seen the building I burnt down after the storm, because it was not snow-covered. A couple of minutes later they turned around and flew back over. Wildly waving at them—they had a perfect view as I was out in the open. My only chance left is that they saw me.”

But the planes did not spot him. Otter returned to the campground, his hope dwindling.

6. The Last Days

At the campground, Otter found a stash of horse feed and made a rudimentary version of oatmeal. He waited in the bathroom, but no rescue came. By December 17, he had lost all hope.

He wrote:

“My intention is to bring the stove inside later and asphyxiate myself. Probably won’t work. Nothing else I’ve tried has. I intend to enjoy my last day, eat my remaining food, stay warm, and focus on the beauty and good things that were my life, especially my friends.”

The bathroom was not airtight. Otter waited a few more weeks. In January, he tried to end his life again, this time by cutting himself with a saw. But this, too, failed. He changed his mind and continued to wait.

In his final days, Otter wrote about his life, recalling pleasant memories from the trail. He expressed regret about consuming marijuana before setting out, but did not blame anyone else:

“This is a situation of my own doing from a life that I led.”

Sometime in mid to late January, Otter died from hypothermia, compounded by starvation and dehydration. He had spent four to six weeks at Logan’s Campground, and just over two weeks at his original campsite. For months, his fate remained unknown.

7. The Discovery

On May 10, 2016, Ian Cromby reached Logan’s Campground. He noticed a pair of homemade skis leaning against the bathroom. Scratched into the door was a warning about a dead CDT hiker. A note read:

“There is a dead human body inside bathroom locked in. It is that of Steven Olshansky aka the otter. Please notify authorities immediately. No joke. Thank you.”

Cromby recognized Otter from missing person flyers posted in every town along the CDT. He hiked out immediately and alerted police in Chama.

It took days for investigators to reach the campground, battling snowdrifts and rugged terrain. But finally, they recovered Otter’s body and journal, bringing closure to the hiking community and his loved ones.

8. The Lessons

Steven “Otter” Olshansky was one of the most experienced backpackers in history. Yet even he made a fatal mistake—hiking out late in the season, underestimating the power of nature.

His story is a harrowing reminder: No matter how skilled you are, the mountains demand respect. Comfort with your abilities can breed complacency, and the wilderness is unforgiving.

Otter’s final journal entries reflect both regret and gratitude. He owned his choices, cherished his memories, and tried to find peace in his last moments.

9. Epilogue: The Trail Remembers

Today, the story of Otter is told among hikers as a warning and a tribute. His name lives on in the annals of the CDT, a legend whose last days were marked by courage, vulnerability, and the haunting silence of snowbound wilderness.

For every backpacker, his story is a lesson: prepare for the worst, respect the wild, and never let pride outweigh caution. The trail does not care how many miles you’ve walked—it demands humility from everyone.