“Kill Me Fast,” Child Begged — But The Mountain Man Gave Her a Doll and a Future

.

.

“Kill Me Fast,” She Begged — But The Mountain Man Gave Her a Doll and a Future

Snow hissed like a whisper across the high country, sweeping over the pines until the world seemed carved from white silence. In these mountains, the wind did not howl; it sang low and mournful, as if the peaks themselves carried old grief in their frozen throats. Eli Harper leaned into that wind, boots crunching through drifts that swallowed the trail. His shoulders were bent beneath a bearskin coat, his breath pluming in gray bursts, his rifle slung across his back. Eli was a man who lived most of his days in solitude, and solitude had taught him there was never much point in running. What waited at the end of every run was always the same: snow, silence, and the echo of one’s own heart.

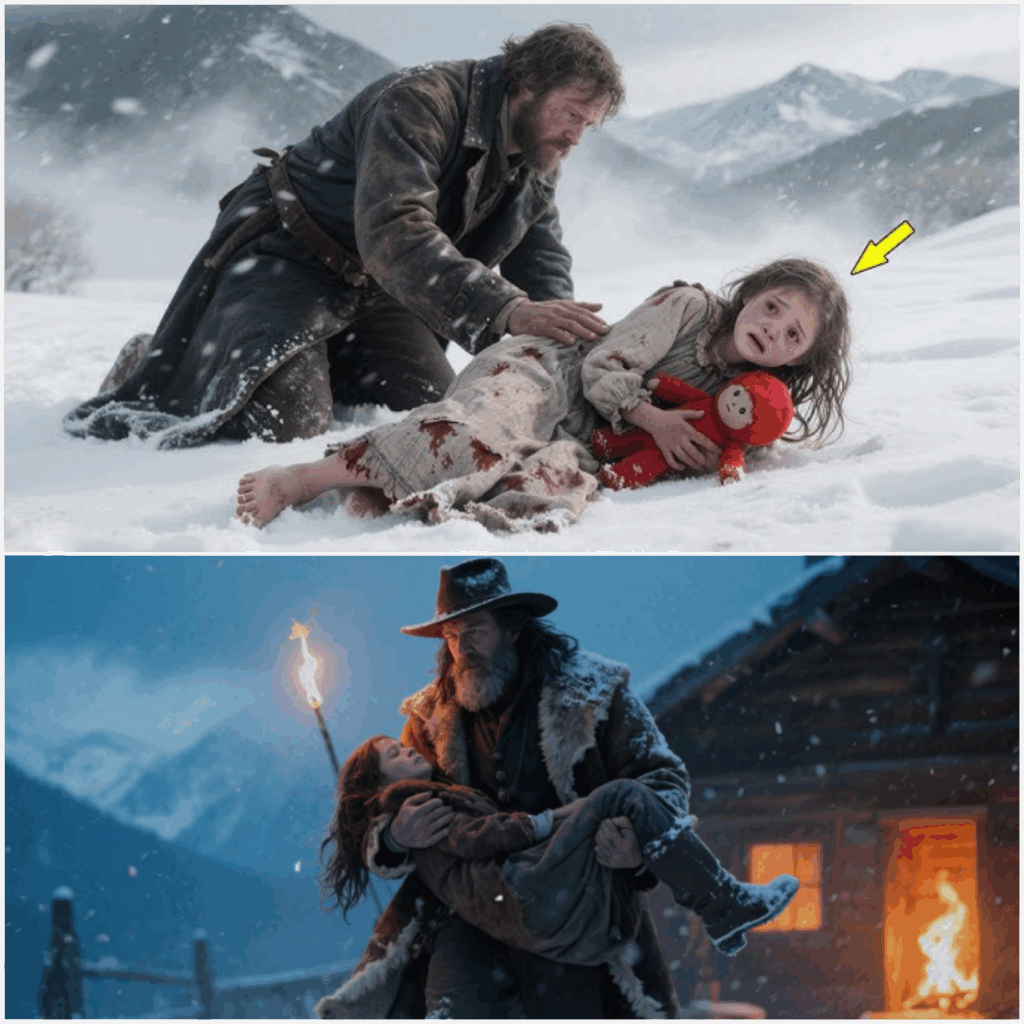

He was three miles from his cabin when he first saw the dark smudge against the endless white. At first, he thought it was a log fallen from some forgotten timber camp, half-buried in the drift. But as he drew closer, he saw it was no log. It was a child, small, curled on itself like a broken bird, a rag of dress frozen stiff against thin limbs. Eli stopped. The snow seemed to still around him as if the world, too, held its breath. He squatted low, knees cracking like old timbers, and reached a gloved hand toward the shape. When he brushed snow from her face, two eyes fluttered open—blue, glassy, and far too old for such a young face.

A whisper scraped past cracked lips. “Kill me fast.” The words were not a cry, but a request—the kind made when hunger has bitten so long that the body no longer trembles at the end. Eli did not answer. His jaw set hard, beard crusted with ice. Something in those eyes pulled at him—not the plea for death, but the weariness of having asked too many times already. He saw, if only for a breath, his brother’s eyes staring at him across years and grave dirt. Josiah, younger, gentler, had died with the same look, begging Eli not for life, but for peace. Eli had not been able to grant it then. He would not grant it now.

He slid his arms beneath the child. She weighed near nothing, a sack of bones wrapped in frost, her breath thin as smoke. She resisted at first, weak claws scratching at his coat, whispering again, “Don’t…don’t save me.” But her hand soon fell limp, and he pulled her tight against his chest, turning back toward the shadow of the trees. Each step broke the crusted snow with a sound like glass shattering. The sky pressed low, heavy with more white waiting to fall. He said nothing to her; he had no words for children anymore. He walked until his cabin rose from the ridgeline, a squat shape of logs weathered gray by years of storms, chimney smoke lifting in faint trails.

He should have left her in the snow, he thought. He should have kept walking, let the wind finish what hunger had started. That would have been easier. But Eli Harper had never chosen the easy thing, and it had cost him everything. Still, he bore her weight inside. The door creaked wide, the smell of smoke and iron filling the air. He laid her on the bedroll by the fire where she shivered violently, though heat licked against her cheeks. He pulled a buffalo hide blanket over her, set a pot of water near the coals, and knelt with stiff movements, every action deliberate, as if performed against some deep reluctance.

Her eyes flicked open again, and she stared not at the flames, not at him, but at the object resting on the shelf above her head—a doll carved of pine, painted long ago with crude strokes of ochre. Its face was simple, its arms stiff, but in a cabin of iron and ash, it was the only thing that carried a breath of gentleness. She reached a shaking hand upward, fingers brushing the wood. He watched her clutch it as though it were the last ember in a cold world. She did not weep, though her lips trembled. She only clung.

The night deepened. Eli fed the fire, spooned broth into a tin cup, and pressed it to her mouth. She tried to drink, choked, and he steadied her head with a hand calloused from years of ax and rifle. “Slow,” he muttered. His voice startled her—low, gravelly, and unused. She blinked at him as though she hadn’t expected he could speak at all. She sipped, then fell into shallow sleep, the doll still in her arms. Eli sat back, leaning against a log wall, staring into the flames.

He should have taken her to town, he thought. The preacher could deal with it, or the sheriff, or maybe the undertaker if the Lord had decided this was already too late. But some part of him, the part that remembered Josiah’s last rattling breath, kept him still. He listened to the fire crackle, to the storm pressing against his shutters, to the child’s faint breathing. Each sound carved a weight heavier into his chest.

Morning brought clearer skies, the snow gleaming under a weak sun. Eli saddled his horse, a gray with frost in its mane, and lifted the child into the saddle before him. She stirred, clutching the doll, whispering words he couldn’t catch. He rode down the ridge toward Ash Hollow, the nearest settlement—a town of fifty souls stitched together by gossip and fear. The townsfolk watched him enter from the boardwalks, eyes sharp. Eli Harper rarely came down from his mountain, and when he did, it was usually for powder, salt, or whiskey. Now he rode in with a child in his arms. Tongues clicked, whispers spread quicker than prairie fire.

He reined up outside Jonah Briggs’ store. Jonah, a thin man with shoulders bent from years of hauling sacks, looked up from sweeping snow from the porch. His eyes fell on the child, then darted away. “Harper,” he said softly, as though saying more might cause harm. Eli dismounted, lifting the girl gently. “She needs bread,” he said, voice flat. Jonah hesitated, then disappeared inside. When he returned, he set a loaf on the counter but did not meet Eli’s gaze. “Best take her to the preacher,” he murmured, glancing toward the crooked church steeple. Eli said nothing. He placed a coin on the counter, took the bread, and turned.

Sheriff Boon Callaway leaned against the hitch rail outside, his thumbs hooked in his gun belt, a wad of tobacco bulging in his cheek. He spat a stream into the snow where it hissed dark against white. “What’ve you dragged in, Harper?” His voice carried the smugness of a man who had never wanted for power. Eli met his stare but gave no answer. Boon tilted his hat back. “That one looks half-dead already. Best let Pike handle her. He’ll send her east with the rest of the strays. Can’t have her haunting our streets.” The child stirred against Eli’s chest, clutching the doll tighter. Eli’s hand tightened around her. His silence was his answer.

Boon smirked. “Suit yourself, but don’t expect Ash Hollow to stomach your charity. Folks say you’ve gone soft, Harper. A man living alone too long can lose his sense.” Eli stepped into the saddle. His voice was quiet, but it carried: “Ain’t your concern.” He rode out as the whispers trailed behind him like smoke.

Back in the cabin, the fire burned bright against the cold. Eli set the bread before the girl, tearing it into pieces small enough for her to chew. She ate slowly, like an animal unsure the food would be taken back. She spoke not a word, but when she finished, she placed the doll carefully on the table before him. It sat there, its carved face staring blankly, as though offering thanks in her silence.

Days stretched. She slept, woke, ate little, then slept again. Eli tended his traps, chopped wood, moved through the motions of survival as he always had. But now there was another rhythm: checking her breathing, placing broth at her side, watching her thin fingers move over the grain of the doll. He did not ask her name and she did not offer it. Words were scarce between them, but silence carried meaning.

One night as snow fell soft against the window, she whispered in her sleep, “Mama.” Eli turned his head sharply, but she did not wake. He stared at her face, at the sharpness of cheekbones on a child who should have been round with youth. He felt an ache he had buried years ago swell in his chest, an ache that whispered of losses never mended. He pressed a hand to his brow, breathed through his teeth, and let the fire’s light wash over them both. Something had shifted. She had asked him to kill her. Instead, he had given her bread, fire, and a doll. Perhaps that was enough. Perhaps it was the beginning of something neither of them yet understood.

As winter thawed and spring crept into the valley, the girl began to stir more often, no longer lost in half-sleep, her eyes watching the fire, then the door, then him. Her silence became one of listening, gathering, learning the shape of the man who had carried her out of snow when she had asked for death. She ate bread in small bites, sipped broth carefully, her hands no longer trembling so much. Each day she held the wooden doll, a kind of anchor against the world.

Three weeks after he found her, she spoke her first word to him. Not a name, not a story—just “fire.” She pointed at the logs, watching as he set them into the hearth. His movements practiced, deliberate, the rhythm of a man who lived by habit. He looked at her, beard bristling, eyes shadowed by years of solitude, and gave a short nod. “Fire.” He repeated it, his voice low, carrying gravel from years of disuse. She seemed satisfied, and though she said nothing else that day, something had cracked open.

From then on she said one word here, another there: water, bread, cold. He answered only when necessary, but he felt the weight of each word like a stone set carefully into a foundation. She was building something, and he was letting her.

When spring finally crept down the slopes, Eli took her with him into town. She had gained some strength, enough to walk beside him, though her steps were light and unsteady. She wore a coat he had stitched together from scraps of hide, the seams uneven but warm enough, the doll poking from her pocket. As they reached the dusty main street of Ash Hollow, people stopped to watch. Whispers rustled like dry grass. Eli felt them even if he didn’t listen. A woman leaned toward another, murmuring, “That Harper’s brought in a stray.” A man on the porch spat and muttered, “She’s half-dead still. Ought not be walking our streets.” Eli walked on, his stride even, his face unreadable. The girl clung tighter to his coat, her eyes darting.

They stopped at Jonah Briggs’ door. Jonah, kind in ways that rarely showed beyond his stooped shoulders, looked at them with a flicker of concern. “Morning,” he said, voice soft. His eyes shifted toward the girl, then back to Eli. “She’s walking now.” Eli gave the smallest nod. “Needs flour.” Jonah measured out the flour, slipping a little extra into the sack without a word. Eli saw it but didn’t comment. Jonah hesitated, then leaned closer, his voice dropping. “Best keep her close, Harper. Boon’s been saying things. Claims you got no business keeping her.” Eli’s jaw flexed, but he said nothing. He set down his coins, lifted the sack, and motioned for the girl.

As they left, Boon Callaway’s gaze followed them across the street, arms folded, a sneer curling his lip. He spat into the dirt and called out, “Ain’t no man’s duty to raise the cursed. Let her go to the preacher, Harper. Save yourself the shame.” The words cut through the crowd, sharp as a blade. Laughter followed from a few, uneasy murmurs from others. The girl shrank behind Eli, her hand clutching his coat with a grip born of desperation. Eli didn’t turn. His silence was harder than words.

Back at the cabin, the silence seemed a relief, but the girl’s shoulders remained tense. That night, she would not touch the bread he set before her. She turned her face to the wall, the doll pressed against her chest. Eli sat by the fire, staring into the flames, his hand wrapped around a tin cup. He knew the sound of words like Boon’s. They stuck like burrs, burrowed deep and festered. He let her be.

In the morning, he found her at the stream behind the cabin, her thin hands dipped into the cold water. She stared at her reflection, gaunt and pale. “They think I’m cursed,” she whispered. It was the first full sentence she had given him. He stood on the bank, boots sinking into mud, and after a long silence, answered, “Let ‘em think.” She turned, searching his face for more. He gave her none. But when she looked back at the water, her shoulders loosened just a little, as if his refusal to argue meant something stronger than comfort.

The weeks turned to months. Eli taught her to split kindling, her small hands steadying the hatchet as he guided her movements. She learned to stir beans over the fire, to mend a tear in a shirt with clumsy stitches. He set traps and showed her how to check them, how to reset the wires, how to be patient with silence in the woods. She watched birds on the windowsill, breaking crumbs from her bread to leave for them. Small gestures became her way of answering the world.

One day, she placed the doll carefully on the table before him, its crude face staring up. She didn’t explain, and he didn’t ask, but the offering settled between them like a vow. He left it there all night, and when she retrieved it in the morning, her expression was lighter.

In town, the whispers grew louder. Pastor Pike preached on Sundays about sin, about charity wasted on those who carried the mark of God’s judgment. He did not name her, but everyone knew. Mothers pulled their children away when she passed, and men spat in the dirt. Jonah Briggs alone gave small kindnesses, slipping sugar or beans into Eli’s sack, but even he kept his head down when others watched. The girl endured the stares with a chin tucked, her fingers white around the doll. Each trip into town carved a wound deeper, but she did not ask to stay home. Eli understood. She was testing herself against their cruelty, refusing to vanish into his cabin as though she were a ghost. He admired her for that, though he never said it. He only walked beside her, his presence a shield.

One evening, thunder rolled over the peaks, a storm shaking the earth with its weight. The girl sat by the window, watching lightning tear the sky. She whispered, “I was alone when the snow came. Alone too long.” Eli, sitting by the fire with his knife paused in his carving. He looked at her, his eyes heavy with things unsaid. “Not now,” he murmured. His voice carried no softness, but it carried truth. She nodded once, her lips pressing together, and turned back to the storm.

Later, when she slept, he placed a new carving on the table, a rough shape of a bird, wings spread. In the morning, she found it and smiled faintly, brushing her fingers over the wood as though it were alive. She placed it beside the doll—two figures now, two small anchors against a world that tried to strip her down to nothing.

By midsummer, she had grown stronger, though still thin, her face no longer hollow but carrying the faintest color. Eli caught her one morning standing in the stream, water lapping at her ankles, whispering, “I’m still here.” She did not know he heard. He stood at the edge of the trees, unseen, his chest tightening at the words. She no longer begged for death. She was fighting for life, and that fight was no longer hers alone. It was his, too.

He turned away before she could notice him. But that night, when he set bread before her, his hand brushed hers by accident. She looked up sharply, and for a moment, their eyes held. Nothing was spoken, but something passed between them, steady as a fire.

The rumors in Ash Hollow did not die. They grew, as all gossip does, feeding on fear. But with each trip into town, the girl walked straighter, her chin higher. Eli noticed, though he never said so.

One evening, as autumn painted the valley gold, she stood in the cabin’s lamplight, her doll cradled in her hands. She looked at him with steady eyes and said, “Lydia Mayfield. That’s my name.” It was the first time she had given it, and her voice carried not hesitation, but strength. Eli stared at her, the name ringing in his ears like a bell. He nodded once. “Lydia.” She smiled faintly, as though reclaiming her name had stitched something torn inside her back together.

That night, he found himself whispering the name to the fire, testing it in his mouth, as though saying it might keep it safe.

But Boon was not finished. His pride could not stomach Eli’s defiance, nor Lydia’s resilience. He began to whisper darker lies, stoking hatred into fire. By October’s end, the whispers had sharpened into plans. Boon gathered men in the back room of the saloon, their faces shadowed in lamplight. “We’ll ride to Harper’s place. Take the girl. Send her east where she belongs. Harper can stand aside, or he can be buried in his snow.”

Up on the mountain, Eli already felt it coming. The woods had their own language, and so did men. He sharpened his rifle, oiled his revolver, but more often he sat by the fire and watched Lydia. She moved with resilience that was its own kind of weapon. Every gesture a declaration that she was no longer the girl who had begged for death in the snow.

The night the mob came, frost already silvered the ground. The moon was sharp above the ridge, torches flickering like angry stars as a dozen riders climbed toward the cabin. Lydia heard them first, the distant thunder of hooves, the faint crack of voices carried on the cold wind. “They’re coming,” she whispered. Eli rose from his chair, the shadows of firelight stretching across his face. He took his rifle from the wall, checked the chamber, then set it aside. His eyes met hers, steady, grave. “Stay close,” he said. She nodded, her jaw tight with something fiercer than fear.

The mob drew up before the cabin, torches swaying, smoke curling into the night. Boon rode at their head, his chest puffed, his voice booming. “Harper, bring out the girl. This ends tonight. She don’t belong to you. She don’t belong here. Hand her over and maybe we’ll leave you standing.”

Eli stepped out onto the porch, the door creaking behind him. The firelight from within spilled around his frame, his rifle in hand, though its barrel pointed to the ground. He scanned the faces—men he’d known for years, men who had shared whiskey with him once, now turned to stone by fear and Boon’s lies. He let his gaze settle on Boon last. “You’ll not take her.” His voice was calm, quieter than Boon’s, but it carried with a weight that made the torches seem to flicker.

Boon sneered, spitting into the frost. “You think you can stand against all of us, Harper? You’re one man. She’s a curse, and you’re damned for keeping her.” Eli’s grip on the rifle tightened. “She’s no curse. She’s a child. You want to damn someone, damn yourself.”

The crowd shifted uneasily. Some lowered their eyes, the torches dipping. Boon’s face darkened. “You always were a fool, Harper, living alone in your hills, thinking you’re better than the rest. Tonight we’ll see what you really are.” He raised his hand to signal the men forward.

Before they could move, the cabin door creaked open. Lydia stepped out, small against the mass of men and horses, the wooden doll clutched tight in her arms. She stood beside Eli, her shoulders trembling but her chin lifted. Her voice, when it came, was thin but clear. “I begged for death once. He gave me life. Which of you would have done the same?” The words cut through the cold like a blade.

The men shifted, their torches wavering. No one answered. Jonah Briggs, standing at the edge, lowered his torch to the ground, shame flickering in his eyes. One by one, others followed, their courage for cruelty dissolving beneath the weight of her defiance. Only Boon remained unmoved, his face twisted with rage. He spurred his horse forward, drawing his revolver. In a blur, Eli’s rifle came up—not to fire, but to knock the revolver from Boon’s hand. The shot cracked into the air, harmless, and Boon tumbled from his saddle into the dirt. Eli stepped forward, towering above him, his rifle barrel pressing down against Boon’s chest. Boon’s bravado crumbled into fear as the mob watched in silence.

Eli’s voice came low, steady as the grind of stone. “You crawl in the dirt you made, Boon. This ends here.” Boon’s eyes darted, searching for allies, but found none. The men turned away, their shame heavier than any law. Boon lay in the frost, broken, his power stripped. The crowd dispersed slowly, torches fading one by one into the night, leaving only the hush of the pines and the hiss of the wind.

Eli lowered his rifle, turning to Lydia. She stood trembling, the doll clutched against her chest, but her eyes met his with a fierceness that steadied him. He placed a hand on her shoulder—not as command, but as acknowledgment. They turned together toward the cabin, the firelight welcoming them back inside.

Winter came soon after, burying the valley in snow. But inside, the cabin warmed and endured. Lydia no longer sat silent at the hearth. She hummed sometimes, soft tunes with no words, while her hands stitched dresses for her dolls. She walked taller now, her steps sure even when the wind howled outside. Eli found himself smiling at moments, faint and rare, when her laughter cracked the air like sunlight through storm clouds.

He was still a man of silence, but his silence had changed. It no longer echoed hollow. It carried the weight of belonging. One evening, as the snow fell thick against the windows, Lydia placed both dolls on the mantle—the old one carved by Josiah, the newer one shaped by Eli’s hand. She stood back, studying them, then whispered, “The past and the future.” Eli glanced at her, the firelight painting his scarred face. He gave a slow nod. “Both worth keeping.”

She smiled faintly, then sat beside the fire, her shoulders relaxed. That night, Eli sat long after she had gone to bed, the fire burning low. He thought of Josiah, of the storm that had taken him, of the charge he had failed. He thought of Lydia, who had begged for death but chosen life, who had stood before a mob and spoken truth into their silence. He realized then that he had not only saved her—she had saved him, too, pulling him back from the hollow where he had buried himself.

He leaned back, the knife resting on the table beside the dolls, and closed his eyes. The storm outside pressed against the cabin, but inside, the fire held. And for the first time in years, Eli Harper believed the future might hold more than endurance. It might hold hope.

.

play video: