“Our Mama Died We’ll Quiet If You Remove Our Sacks” Weeping Girl Promised, Giant Rancher Had No Idea

.

.

Our Mama Died, We’ll Be Quiet If You Remove Our Sacks: A Rancher’s Winter Promise

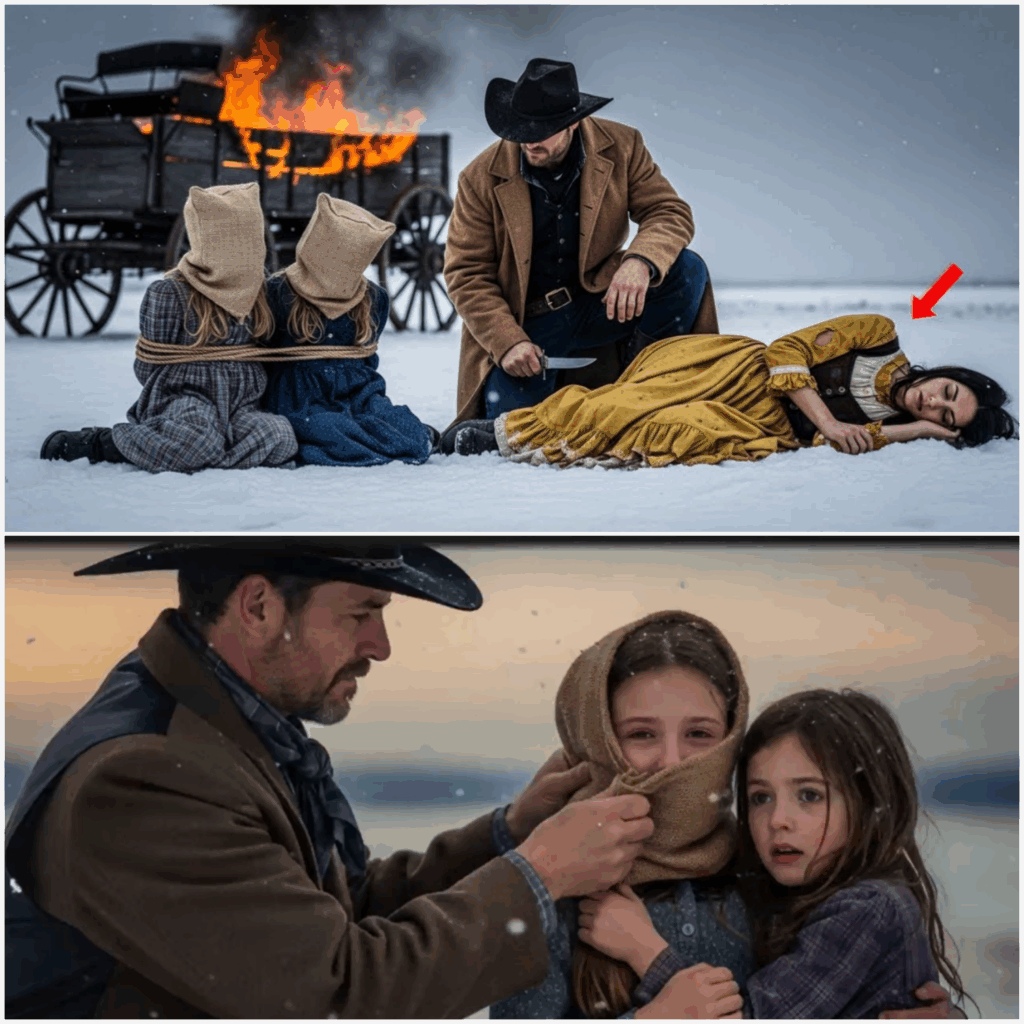

Snow fell like sifted ash from a broken sky, soft and soundless, veiling the prairie in pale grief. The land stretched wide, white and empty, broken only by the charred ribs of a wagon still smoldering where flames had chewed through its frame. Near it, slumped against the frozen ground, lay the still figure of a woman, her dress stiff with ice, hair tangled with frost—a mother who would not rise again. And beside her, two small girls sat in the snow, their hands bound and faces hidden beneath coarse burlap sacks. Their tears were muffled by cloth, but their trembling carried louder than screams in the desolate silence.

From the ridge came a lone rider, his horse’s hooves crunching in rhythm with the hush of falling flakes. He was a large man, shoulders broad beneath a weatherworn coat, his hat brim dusted white. He had the look of someone used to the long silence of winters, his gaze steady and his jaw set against the cold. Yet even for him, this scene pressed hard against the heart, for there is no sight more hollow than children left to the mercy of snow.

He dismounted without a word, boots sinking deep into frost. The horse snorted, uneasy near the burned wreck, but the man’s hand brushed its flank in quiet command. He stepped forward, his shadow falling across the two small figures. At the shift of light, the older child stiffened, her tiny shoulders tightening beneath her thin dress. The younger leaned against her, rope binding their wrists so tightly the skin beneath was raw. For a long moment, he did not move, only studied them, as though the world itself demanded silence before it could change.

The charred wagon creaked in the wind behind them, a skeletal witness to ruin. At last, from beneath one of the sacks, a muffled voice whispered, thin, hoarse, and full of desperate promise. “We’ll be quiet if you take it off,” the older girl said, her words breaking against the cloth like water against stone.

The rancher’s breath left him in a slow cloud. He crouched down, one knee pressing into the frozen crust of snow. His hand, large and calloused, reached for the rope, fingers brushing against the girl’s trembling wrist. She flinched, then went still, as though deciding whether trust was heavier than fear. With a small flick of his knife, the rope fell loose into the snow. The girls pulled their hands to their chests, rubbing their wrists with a tentative touch unused to freedom. He untied the sacks one at a time. When the first fell away, pale daylight struck the face of a child no older than six—cheeks wet, eyes red-rimmed but wide with a strength far beyond her years. Her hair clung in damp strands to her forehead, and she stared up at him, trying to gauge if he was danger or deliverance.

The younger, barely five, blinked rapidly when her sack was removed, squinting against the light. Her lips trembled, but no sound came forth. The rancher said nothing. Words felt too heavy for air already laden with loss. Instead, he reached to the ground, lifted the rope, and tossed it aside as though declaring it no longer had claim over them.

The older girl swallowed hard, glanced once toward her mother’s body lying stiff near the wagon, then back at the stranger. Her voice quavered, but did not break. “Is she asleep?” the younger finally asked, her voice a breath of innocence, struggling against truth. The man’s jaw clenched. He did not lie, yet he did not speak the cruelty outright. He only lowered his hat in quiet respect toward the woman in the snow. The oldest understood. Her eyes followed the gesture, and tears welled again, but she said nothing. She placed her small arm around her sister’s shoulders, the way a child should not have to.

The rancher looked at the girls, then at the burned wagon, and something inside him shifted like ice cracking on a river. He had meant only to pass through these plains, his life kept simple and solitary. Yet here was the choice the world had set before him—two children, a dead mother, and silence that could not be left to swallow them. He removed his coat and laid it gently over the mother’s body, a dignity she deserved even in death. The act drew a small gasp from the older girl, as though she had not expected such reverence from a stranger.

He straightened, snow clinging to his knees, and looked once more upon the girls. They sat huddled together, eyes wide, their breaths puffing small clouds into the freezing dusk. The wind carried a whistle through the charred beams of the wagon, a sound like mourning. The rancher held out his hand, rough and steady. The older child stared at it, torn between fear and a flicker of hope. She reached slowly, her fingers tiny against his palm, and when he helped her rise, the younger followed without question. He lifted them both, one on each arm, against his chest. Their small bodies were cold, rigid with tension, yet they clung to him instinctively, the way drowning souls cling to driftwood.

Snow swirled around them, covering tracks, burying memory. He turned toward his horse, carrying the weight of two fragile lives that had already seen too much of death. Behind him, the burned wagon groaned, then fell silent. Before him stretched only snow, horizon, and the uncertain mercy of what came next. As the girls’ heads rested against his shoulders, the older whispered again, barely audible against the storm’s hush, words meant not for him, but for herself. “He didn’t leave us.”

The rancher paused, boots rooted in the snow, the weight of her words pressing heavier than both children together. For the first time in many years, he let the faintest breath of warmth soften his face, though he kept his eyes fixed on the horizon. The firelight of his cabin far away seemed suddenly closer, as though waiting.

The cabin crouched against the wind like an old man with his back bent to weather. Its logs were darkened with years of storms. The shutters rattled softly, and the chimney gave only a thin coil of smoke to the gray evening sky. When the rancher pushed the door open, the warmth inside was faint but real, a fire low in the hearth casting its orange breath across the worn floorboards. He ducked slightly as he carried the two girls across the threshold, his boots knocking loose the crusted snow from their soles.

Inside, the silence was thick, broken only by the pop of embers and the faint rustle of dry pines stacked near the wall. He set the girls down gently, their faces pale and stiff, their eyes darting around the single-room home. It was not much—a table scarred with knife marks, two chairs, a shelf of tin dishes, a cot in the corner—but it was safe from the snow, and safe was something they had not known in too long.

The younger clutched the charred doll against her chest, staring at the flames as though uncertain whether fire was friend or foe. The older girl stood a little straighter, her small chin lifted in defiance of fear, though her hands trembled. She eyed the door as if weighing how quickly it might close again, leaving them outside.

The rancher noticed, but said nothing. Instead, he hung his coat on a peg and bent to stir the fire. Sparks leapt, flaring light across his face, carving the hard lines of someone who had lived with solitude too long. He moved about the room with quiet efficiency, pouring beans into a pot, laying cornbread on the hearthstone to warm. The smell filled the air, simple and earthy.

The girls sat side by side at the table, stiff and silent, their boots dangling above the floor. They did not reach for each other, but their shoulders touched, and that small contact was enough to keep them steady. When the food was ready, he set the pot down, slid two tin plates across the table. He did not serve them as one might serve children, but placed the spoon between them as though offering choice, not command.

For a moment they only stared. Then the younger dipped the spoon, her hand shaking, and filled her plate. She passed it wordlessly to her sister, who did the same. They ate in small bites, their eyes on the table, as if afraid a sudden sound might take it all away. The rancher ate little, watching without staring. His thoughts drifted unbidden to the empty nights he had spent at the same table, his only company the creak of the rafters and the sigh of wind through cracks in the logs.

The cabin had been built for one life, not three. Yet now the scrape of spoons and the sound of children breathing filled the air with something he had not heard in years: the shape of belonging.

On the shelf above the hearth sat the doll’s broken head, retrieved from the wagon, though ruined. He had placed it there absent-mindedly, unsure why he hadn’t left it behind. When the younger girl saw it, her spoon clattered against her plate. She slid from her chair, climbed onto the hearth’s edge, and reached for it with both hands. The rancher started forward, but stopped when he saw her expression—not fear, but reverence. She held the doll’s head close, pressing it to the body she had carried. The seam did not fit, yet she whispered, “Mama fixed her once. She can be fixed again.”

The rancher’s throat tightened. He did not tell her some breaks never mend. Instead, he picked up a small scrap of leather from the shelf and handed it to her. “For her dress,” he said, his voice low and rough. The child looked at him startled, then nodded solemnly. It was the first time she had looked directly into his eyes.

The night deepened. The wind howled, rattling the shutters. He laid extra wood on the fire and pulled a blanket from his cot. The girls curled together on the floor beside the hearth, the doll clutched between them. Their breathing softened, their bodies finally surrendering to sleep. The rancher watched, leaning against the table, his arms folded. He saw how the older girl, even in slumber, kept one hand on her sister’s shoulder, guarding her still. He saw how the younger sighed, her lips forming a faint smile as warmth touched her face.

Four years the cabin had been hollow, a shelter with no echo of laughter or voice. Now, with the girls curled before the fire, it seemed less like walls and more like a beginning.

Yet the weight of choice pressed heavy. He had brought them here, yes, but what then? Tomorrow the town would see them. Questions would be asked. Gossip would coil like smoke. He could almost hear the mutters: a single man with two strange girls—what’s his game? The fire cracked, scattering sparks up the chimney. The rancher pressed a hand to the table’s edge, steadying himself against the flood of old doubt. He had lived quiet for a reason, away from the judgments of others. Yet as he looked at the children wrapped in sleep, he knew silence would no longer keep him. Their presence was a vow already made.

Outside, the storm gathered, battering the roof with snow. Inside, the fire’s glow softened every corner. The rancher pulled the second chair close to the hearth, set it beside the first, and left it there—a quiet preparation, as though for two small occupants who did not yet know they had a place.

As he turned back, the older girl stirred, eyes half-opening, whispering in a voice worn with sleep, “Don’t leave us.” He did not answer, but his hand lingered on the chair he had set by the fire, as though the wood itself might speak the promise he could not yet give aloud.

The storm passed, leaving the world scoured clean, but the silence it left behind was sharper than the wind had been. The rancher rose before dawn, feeding the fire, his movements deliberate as the two girls stirred in their makeshift bed of blankets by the hearth. Their eyes blinked open, still red from sleep, their faces pale against the glow of the embers. They clung to each other, small hands wrapped tight, as if waking might scatter them into the snow again.

He set a tin plate of cornbread between them without a word. They ate slowly, glancing at him from time to time, as though waiting for the moment he might send them away.

By midmorning, he saddled his horse. Supplies were running thin. The cabin, sparse even for one man, had no room for extra mouths. He did not explain himself, but when he lifted the girls into the saddle and climbed up behind them, they seemed to understand that the journey into town was not a choice, but a necessity.

The older girl clutched the reins with stiff fingers, pretending it was her hands guiding the horse. The younger leaned against him, clutching the broken doll’s patched body close to her chest. Snow crunched beneath the hooves as they rode the long miles. The sky was pale, the horizon washed in white. He kept a silence, but the girls spoke in whispers too low for him to hear, their heads tilted together as if they shared secrets against the vastness of the land.

When the outline of the town rose ahead, the older girl stiffened, her jaw set. The younger buried her face in his coat, trembling before a place filled with strangers.

The town was alive with voices, doors swinging open, boots thudding on packed snow. Folks glanced up when they saw the rancher ride in with the two girls pressed close against him. Their stares followed him down the main street, suspicion whispered in the curl of smoke rising from chimneys.

He dismounted in front of the mercantile, lifted the girls down, and took them by the hand. His silence was not defiance, but steadiness, though the weight of eyes was heavy. Inside, the warmth smelled of leather and flour. Shelves lined with jars and folded cloth loomed high above the girls, who shrank beside him, wide-eyed.

The shopkeeper, a man with narrow shoulders and a sharp gaze, looked from the rancher to the children, his expression pinched. “You’re taking on strays now?” he asked, his voice edged with mockery.

The rancher said nothing. He set flour, beans, and candles on the counter, his broad hand steady. The shopkeeper leaned closer, lowering his voice, but not enough to keep it from carrying. “A man alone ought to explain himself. Folks are bound to ask questions.”

The rancher’s jaw tightened, but he did not answer. The older girl, standing rigid by his side, flushed crimson. She clutched her sister’s hands so tightly the younger whimpered. And then, with sudden courage that startled even herself, the girl stepped forward.

“Our mom is dead,” she said, her small voice cutting the silence sharper than a blade. “He didn’t take us. He found us.”

The store went quiet. Even the crackle of the stove seemed to hush. The shopkeeper blinked, thrown off balance, but before he could reply, the rancher placed a silver coin on the counter, gathered the parcels, and turned away. He guided the girls toward the door, his silence heavier than words.

Outside, the cold air rushed against their faces, and the older girl’s shoulders shook. She pressed her lips tight, but her eyes shimmered with tears she refused to shed. They walked down the street, the weight of gossip trailing behind them like a shadow. Men leaned against posts, whispering. Women glanced from doorways, their faces full of judgment disguised as pity. The younger girl clung tighter to his leg, hiding her face from the looks that followed.

The rancher kept his head high, boots steady in the snow, but each step carried the press of old memories, of whispers that had once driven him into silence, of accusations he had never answered. When they reached the edge of town, the girls climbed onto the horse again, their small figures huddled beneath his coat. The older girl looked back once at the row of buildings, her eyes narrowing as though memorizing the shape of their scorn. She did not speak until the town was a shadow behind them. “They think bad of you,” she whispered, her voice wavering.

The rancher gave no reply. Instead, he kept the horse steady, carrying them back across the white expanse toward the cabin. The wind rose, scattering their trail behind them until it was as though no one had passed at all.

When they returned, the fire still glowed faintly in the hearth. He set down the parcels, stacking wood against the wall. The girls watched him, silent and uncertain. Then, without a word, he fetched a block of pine, his knife flashing in the firelight as he carved.

The older girl crept closer, her eyes following each motion. Shavings curled onto the floor, pale ribbons against the dark wood. Slowly, a shape emerged—a small chair, rough but sturdy. When he set it by the hearth, the younger girl climbed onto it at once, her face brightening as though a place had been made for her at last. The older girl stood watching, her lips parted, torn between gratitude and disbelief.

As the flames crackled higher, he reached for another block of pine. His knife touched the wood, carving with quiet patience, as if the act itself was an answer to the questions left unspoken. The older girl’s voice trembled as she whispered almost to herself, “He’s building us something.” And for the first time since the snow had swallowed their world, she allowed herself to believe they might not be left again.

The storm came down from the mountains in the night, a wall of wind and snow that shook the shutters and pressed the cabin tight against the earth. The rancher rose from his cot and fed the fire until the flames licked tall, their glow reaching every corner of the small room. The two girls huddled together on the little chairs he had built, their blankets pulled up to their chins, eyes wide as thunder rolled faintly behind the roar of wind.

Outside, the world was erased, only whiteness and fury beyond the walls. Inside, their breaths mingled in quick clouds, fear thick in the silence. The older girl tried to keep her chin high, though her lips trembled. The younger pressed her face into the doll’s patched body, whispering as though the ruined toy could still keep watch.

The rancher knelt by the hearth, checking the wood pile, calculating how long it would last if the storm held. He had seen winters swallow weaker men, had buried neighbors whose doors had not held. His hand lingered on the axe handle, the weight of old battles against cold and hunger pressing on him. But when he looked back, it was not his own survival at stake anymore.

The fire cracked, throwing sparks. The cabin groaned as the wind battered the roof. The girls flinched, clutching at each other. The rancher stood, walked to the door, and braced his body against it as the gale shook the hinges. His frame filled the space like a wall of oak, shoulders squared, jaw locked, silent but unyielding. Snow slipped through the cracks, stinging cold against his face. Yet he did not move. He stood as if to tell the storm itself, “Not tonight.”

The younger girl finally rose from her chair, small feet padding across the floor, her blanket trailing behind her. She stopped beside him, staring up at the broad figure holding the door against the dark. “Papa wouldn’t have stayed,” she whispered, her voice thin but certain. “But you didn’t leave.”

Her words cut through the howl outside, sharp as truth laid bare. The rancher’s eyes closed for the briefest moment, as though the weight of them pressed into places no storm could reach. When he opened them, his gaze was steady—the silence of a man who had just been given a name he did not expect to carry.

The storm raged through the night, battering, clawing, but the cabin held. The fire burned down to embers, then flared again as he fed it, each log thrown on like a promise renewed. The girls drifted to sleep against him, their heads heavy on his chest, their small breaths warming his coat. He did not rest, but sat still, his arms around them, his body a shield.

His thoughts wandered to years of solitude, of nights spent listening only to the wind. That life seemed far away now, as though it belonged to another man.

Toward dawn, the storm broke. Snow still fell, but gently, a hush after fury. The horizon was washed in pale light, the world buried in white silence.

The rancher pushed the door open, stepping outside into the clean stillness. The girls followed, their eyes wide at the sight of drifts taller than fences, trees bowed under the weight. The air was sharp but alive. They stood in the snow, their small figures bundled in blankets, and for the first time in days, they smiled without fear.

He led them to the edge of the yard where the storm had heaped the snow high. Together they began digging a path, his shovel carving steady lines, their tiny hands scooping at the edges. Their laughter rose faintly, carried on the brittle morning air, awkward at first, then freer. It was a sound the cabin had not heard in years, and it clung to the frost like something determined to stay.

When the path was clear, he carried them back inside, their cheeks flushed with color, their breaths quick. He set them by the hearth again, fetched two bowls, and filled them with the last of the beans. As they ate, he pulled the second small chair closer to the fire, the one he had been carving the day before. It was rough, uneven, but when he set it beside the first, the two seemed a pair. The girls leaned against them, each taking a place as though they had belonged there all along.

The older girl set her spoon down and looked at him, her eyes clearer now, the shadows less deep. “Are we staying?” she asked. Her voice did not beg this time, only asked, steady and expectant.

The rancher felt the question settle heavy in his chest, heavier than the storm’s weight against the door. He looked at the two small chairs by the fire, at the doll patched and held close, at the faces waiting for an answer. He reached for a strip of leather he had left on the table, slid it across to the younger girl, who brightened instantly, seeing it as material for the doll’s dress. Then he placed his broad hand flat on the table between them, a quiet gesture firm as a vow.

“If you want to,” he said at last, voice low, carrying the weight of more than words.

The girls exchanged a look, silent agreement passing between them. The older girl’s lips trembled, but a smile broke through. She reached out, her small fingers brushing against his hand, then staying there. The younger followed, pressing hers on top, their fragile touch steadying his.

The fire roared higher, casting light across the cabin walls, filling every corner with warmth. Outside, the snow lay deep, erasing every trace of what had come before. Inside, something new had taken root, fragile, yet undeniable. The rancher sat back, watching them, his silence full now, not of emptiness, but of belonging.

As the girls leaned into him, the older whispered with certainty, “This feels like home.” The rancher closed his eyes, the storm’s echo fading, replaced by the sound of two small hearts beating against his own. Something worth keeping at last.

.

play video: