She Collapsed After the Lashes for a Native Girl—But Five Comanche Brothers Crowned Her With Honor

.

.

No Child Alone

In a sun-drenched town where the shadows of cruelty loomed large, a crowd gathered at noon, drawn by the spectacle of punishment. The whipping post stood in the center of Dust Haven, an ominous reminder of the harshness that governed their lives. A native girl, perhaps twelve years old, clung to the stake, her small body trembling as she breathed through a gag that should never have touched a child. Norah James, a weary woman who scrubbed floors at the local boarding house, felt something harden behind her ribs as the mayor droned on about charges: insolence, stealing biscuits, speaking to the wrong people.

As the mayor’s voice droned on, Norah’s heart raced with a mix of anger and fear. She had seen the girl before, her bright eyes dimmed by the weight of the world. The townsfolk snickered, their laughter a cruel echo in the oppressive heat. When the lash raised its shadow, Norah stepped forward, tearing off her own apron strings. “Leave the child. I’ll take it,” she said, her voice steady as a nail.

The crowd fell silent, disbelief hanging in the air. Someone muttered that orphans were made for such work, but Norah’s gaze was fixed on the girl. The child’s wide, unblinking eyes found Norah’s, and in that moment, a bond was forged—a connection that transcended their circumstances.

As the first stroke fell, a searing pain shot through Norah’s back, the whip biting into her skin. The second stroke buckled her breath, but she held firm, determined to shield the girl from the cruelty of the world. By the sixth lash, she bit down on her own blood, tasting the iron and dust that filled her mouth. Memories of kindness washed over her—of a bread bundle she had tied for strangers last winter, seamed with blue double thread she could always recognize.

Each stroke felt like a hammer driving nails into her resolve, but she refused to falter. The ninth lash brought forth a wave of dizziness, and by the tenth, her knees gave way. She collapsed, cheek pressed to splinters, her back raw and torn. The crowd remained silent, the spectacle of her sacrifice leaving them in a state of shock.

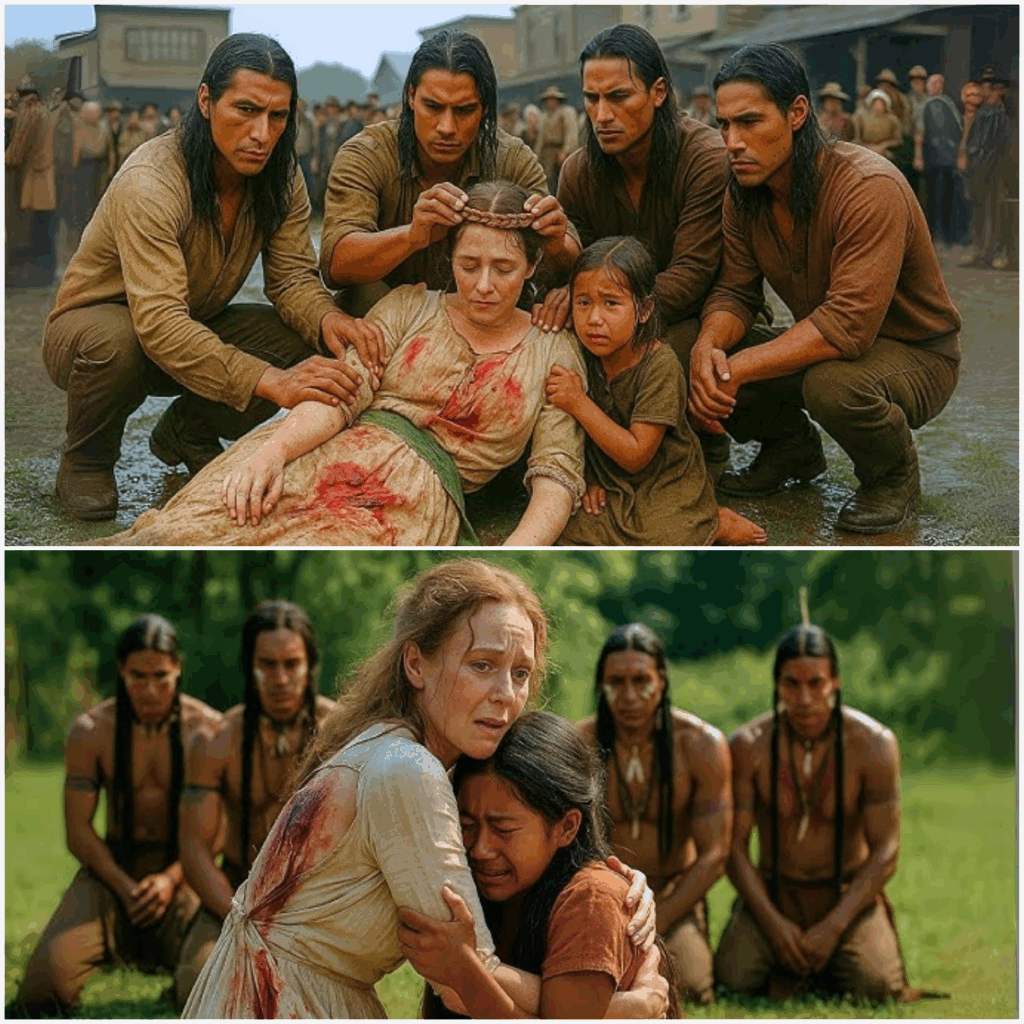

No one saw the five riders until sunlight turned to dust around their horses. They dismounted in unison, and the square learned another kind of silence. They were brothers—Comanche men whose presence drew breath from the crowd. The eldest raised an open hand, and the ropesmen froze, sensing the shift in the atmosphere.

The youngest knelt beside Norah, sliding an arm beneath her head. He stared at her torn hem with a shock that didn’t belong to this hour, as though the blue double thread there had spoken his name. Loosening a thin strip of the same thread tied at his wrist, he met his brother’s eyes. They did not threaten; instead, all five went to their knees at Norah’s side, forming a circle in the dust, heads bowed to the woman who had bled for a child not her own.

From their belts, they drew plain rawhide—reins cut short, boot laces—and the middle brother braided them with careful hands into a simple band, no richer than a shoelace and somehow heavier than iron. The eldest lifted Norah’s head gently while the youngest set the band above her brow, careful of her wounds, as the others kept their palms open to show no harm would come.

The eldest offered the only words they carried for such an hour to the girl and to the town that had come to watch pain like theater. “No child alone.” The fifth brother repeated it, and the words traveled through them, reaching the girl, who whispered them back.

The mayor, sensing his authority slipping, tried to speak but discovered it cost more than he had. The men at the rope found there was nothing to pull when the square refused to move. The youngest lifted Norah, and the middle brother poured water along her torn back, hands steady, the rawhide band catching the sun.

When Norah’s lashes fluttered open, she saw five strangers kneeling, the girl freed and clinging to a sleeve, and townspeople standing as though someone had opened a window inside their chests. A woman crossed with her shawl for Norah’s shoulders. A farmer stepped forward with his hat. A boy who had laughed pressed his lips white and stopped.

The brothers rose together, carrying Norah from the post through a lane the crowd made without being told. Behind them, the stake stood naked in the noon, its shadow smaller than the people who had built it. At the corner, the youngest glanced at the faint mark the blue thread had left on his wrist, then at the matching stitch on Norah’s torn hem. He saw her, not with pity, but with recognition.

They carried Norah into the shade of the livery, the five Comanche brothers moving like a single body, the youngest still cradling her head against his chest, while townsfolk trailed behind. Guilty silence pressed on every bootstep. The native girl who had been spared clung to Norah’s apron hem, refusing to let go, even when the eldest brother knelt to check Norah’s pulse.

Her breath came shallow, lips cracked, skin fevered from lash and heat, yet her eyes opened to slivers and found the girl first. “You’re safe now,” she whispered. The girl’s tears fell hot against her wrist. Elias, the eldest, tore linen from his own sleeve and pressed it to her wounds, while Mateo barked at the stable boy for clean water. In a place where Comanche presence usually drew spit and slurs, the boy obeyed without question, his hands trembling.

When the water came, it was the third brother, Raphael, who knelt and poured it slowly down Norah’s back, his voice low as he said in halting English, “You held pain that was not yours. No child alone. That is our vow.” Norah’s gaze fluttered to him, confusion threading with pain. She tried to speak but coughed, and the fourth brother, Thomas, pressed a cup to her lips, steadying her trembling hands.

Gabriel, the youngest, who had noticed the blue double thread at her apron hem, touched it gently now, his thumb brushing over the seam as though it were a relic. “You stitched with care,” he murmured, not to shame, but to acknowledge. When she met his eyes, she saw not pity, but recognition, a silent respect that steadied her more than the water.

Behind them, townsfolk lingered uneasily, watching five men who had come not with rifles, but with honor, kneeling for a stranger they had no blood tie to. Some muttered uneasily, “How could an orphan woman and Comanche warriors share anything?” Others looked away in shame, remembering the laughter they had loosed when the whip first cracked.

It was the mayor who broke first, pushing through with bluster, voice raised as though noise could undo what honor had stitched in silence. “This is disorder,” he barked. “She interfered in lawful punishment. You five have no claim here. Dust Haven’s justice belongs to Dust Haven.”

Elias rose to his full height, tall as the barn’s doorway, blood still wet on his torn sleeve. “Justice,” he said, the word ground like stone. “To whip a child until she breaks. Make a crowd of your neighbors laugh at her pain. That is not law. That is cowardice.”

The words struck like hammers, and the people shifted, some lowering their heads, a few nodding quietly. The mayor flushed, but before he could bark again, Norah lifted her head from Gabriel’s arm. Voice hoarse, but clear enough to carry, she said, “If you call it law, then let the same rope bind you too, because I saw no crime, only hunger and fear.”

She faltered, nearly collapsing again, but Gabriel steadied her, his hand firm at her shoulder. “You will not stand alone,” he said, and the brothers spoke the vow together, low and steady in their own tongue, ending in English. “No child alone.”

The words moved like wind through dry grass, catching ears that had never heard them before. Women exchanged looks, clutching children closer. A boy who had jeered earlier whispered the words back, ashamed. In that moment, the phrase stopped being Comanche alone and became human.

The mayor spat, but his voice no longer carried. The crowd was already shifting, no longer his. Clara Jenkins, who ran the bakery, stepped forward and laid a loaf in Norah’s lap, eyes wet. “She bled for a child,” Clara said, voice breaking. “I’ll bake for her as long as I flour.”

The words cracked the silence, and others began to stir. Small acts rising like embers while the brothers held their circle around Norah, not as warriors threatening war, but as men who had chosen honor over fear, showing Dust Haven what true justice looked like.

By evening, Dust Haven was split down its single dusty street, half the town whispering of shame, the other half whispering of honor, as though the square itself had been cut in two by the sight of one woman collapsing under lashes and five Comanche brothers kneeling at her side.

Inside the livery loft, Norah lay on a bed of hay softened with quilts townsfolk had slipped in when no one was looking. Her back raw and bandaged, each movement igniting fire under her skin. The Comanche girl she had saved curled near her feet, refusing to sleep anywhere else, while the brothers kept quiet vigil in turns, their presence both shield and signal.

Every knock on the stable door brought tension. Sometimes it was Clara from the bakery bringing broth, sometimes a ranch boy carrying water, and sometimes only silence outside, the sound of boots shifting. Watchers debating if mercy was weakness.

The mayor sat in his parlor, fuming, red-faced under the lamplight, his pride bruised deeper than any lash. To lose control of a crowd, worse, to lose it to an orphan and five natives, was a humiliation he could not swallow. He called for men who owed him debts, promising coin and favors if they would speak loudly in the saloon, turning the story on its head. Norah had dishonored the town. Norah had made them look weak. Norah consorted with savages.

The whispers spread like rot, and by nightfall some repeated them, eager to cling to the mayor’s shadow rather than face the light of their own conscience. In the loft, Norah woke gasping, sweat soaking her shift. Gabriel, the youngest, pressed a cloth to her brow, his voice calm as still water. “Pain makes lies sound louder,” he told her softly. “But truth waits, steady like stone. Don’t fear what they shout tonight.”

She tried to smile but winced instead. “I wasn’t brave,” she whispered. “I just couldn’t stand by.” Elias, the eldest, who leaned against the post with his arms crossed, said in a voice low but unshakable, “That is the only kind of bravery there is.”

His words steadied her more than the poultice. Outside, laughter rose from the saloon, sharp and jeering, the words clear enough to carry. “Savage lover, blood traitor, orphan trash.” Norah flinched, but the brothers did not move toward the sound. Instead, Raphael spread a blanket more firmly over her, saying, “Let them spend their breath. Tomorrow, they will need it for truth.”

But the mayor’s plan was not only words. At his table, he drafted a petition, writing in his heavy hand that Norah James endangered public order, that the Comanche brothers had trespassed into town with force, that law would collapse if honor were mistaken for justice. He sealed it with wax and pressed it into the hands of a writer bound for the county judge.

“We’ll see how far their honor carries,” he muttered. Back in the loft, Norah stirred again, and Thomas, the fourth brother, told her gently of how once, years ago, their sister had been accused unjustly. They had sworn among themselves a vow that no child, no woman would ever stand alone again if they had breath left.

Norah listened, tears sliding silently into her hair. And though the night outside seethed with whispers and plotting, something firmer took root inside the livery, something stronger than law or fear.

By dawn, the whole of Dust Haven seemed to breathe in two different directions. Half the town moving with quiet steps toward the livery where Norah lay, the other half crossing the street to avoid it, as though mercy itself were a contagion. The bakery woman came again, this time with biscuits wrapped in cloth, whispering that she had heard men in the saloon planning to drive Norah out by sundown.

A rancher’s boy slipped in behind her, leaving a tin of milk without a word before hurrying back to his father, who still cursed Norah’s name. Outside, men loyal to the mayor gathered in knots, pretending at casual talk, but carrying rifles across their shoulders in broad daylight. Inside the loft, Norah shifted restlessly, her back burning. The Comanche girl curled tightly against her side as though shielding her in return.

Elias, the eldest brother, leaned on the window frame, scanning the street below with an expression carved from stone, while Matteo sharpened a knife with slow, steady strokes, though his eyes kept sliding toward Norah, as if to reassure himself she still breathed. Gabriel, the youngest, sat at her bedside, threading strips of rawhide together into a crude crown, his brow furrowed in thought.

“This town wants to choose,” Raphael said quietly, his voice carrying across the loft like the rustle of dry grass. “They will not stand in silence much longer. Either they join us or they join him.”

Norah stirred, opening her eyes enough to catch their words. And though her throat was raw, she whispered, “I don’t want anyone hurt because of me.” Gabriel looked at her, his gaze steady. “You bled for someone who was not you. That choice already changed this town. Now it must decide what kind of people it wants to be.”

The words lingered heavy in the rafters.

By mid-morning, Clara Jenkins, the baker, stood outside arguing with the mayor himself. “She saved a child, George,” Clara snapped, her voice shaking but loud enough for neighbors to hear. “If you call that a crime, you’d better arrest every mother in town.”

The mayor’s face flushed crimson as he shouted back, “She shamed us before outsiders. She made a fool of Dust Haven.”

People paused at their chores to listen, some nodding with Clara, others muttering that George was right, that mercy would only weaken the town’s law. In the loft above, Norah heard the voices carry, and felt her heart seize with guilt. But Gabriel touched the crown of rawhide he had woven, placing it lightly in her palm. “Hold this,” he said softly, “until you believe you deserve it.”

She looked down at the rough braid, tears blurring her sight, and for the first time since the lash had fallen, she let herself imagine a life not defined by pain, but by honor, freely given.

By afternoon, the mayor had gathered his loyalists in the square, nearly two dozen men with rifles and hard faces, their boots planted wide, as if fear could be beaten back by stance alone. He stood at their front, puffed up like a rooster, voice carrying down Main Street. “This is the last day we let outsiders shame our law. That orphan is no savior. She is disorder, and those five Comanche only came to claim us weak. We’ll drive them all out before sundown.”

His words rippled through the town, drawing wives and children to doorways, some nodding grimly, others paling with shame. In the loft, Norah heard the crowd, her throat dry. “Let me go,” she whispered, pushing against the quilt. “If I leave, maybe they’ll stop.”

Gabriel pressed her back with a gentleness that brooked no refusal. “You gave your back for a child. We will give ours for you.”

Then a cry split the square, not from the mayor’s men, but from the bakery door. Clara Jenkins had marched forward, flour still dusting her hands, dragging behind her the very Comanche girl who had been spared the lash. The child’s small hand clutched Clara’s apron, her eyes wide but determined.

“You call this justice?” Clara shouted, her voice quivering with fury. “Then you call yourselves liars. That girl did nothing but live, and Norah James bled for her while you laughed.”

Murmurs rose. Some men shifted uneasily, rifles lowering a fraction. The mayor sneered. “You’d have us bow to a savage child?”

Clara turned to the crowd, her hand trembling as she lifted the girl’s wrist. “Bow to a child? No. Bow to decency. Bow to the truth you all saw with your own eyes.”

Then, in a moment no one expected, the girl herself pulled free and walked into the square, tiny and shaking, but unflinching. She lifted the hem of Norah’s torn apron Clara had brought with her, showing the blood stains still stiff in the fabric.

Gasps rippled. Women wept. Men swallowed hard. The image of that ragged cloth was louder than any speech. From the loft, Gabriel saw it and whispered, “Now they know.”

The brothers exchanged a glance, and in a single motion, all five descended into the square, not with weapons, but with open hands. They knelt together around the child, heads bowed, repeating in one voice, “No child alone.”

The words struck like a hammer against the mayor’s bluster. Farmers lowered their hats. A blacksmith stepped forward and laid down his hammer at the child’s feet. “She’s right,” he said. “Norah is the only one who showed us honor.”

The square cracked open, some still clinging to the mayor’s shadow, but others stepping across to stand near Clara and the girl. The line between law and decency had been drawn in the dust, and the town could no longer look away.

The square had barely settled into uneasy silence when the mayor stepped forward, his boots grinding over the dust as if to erase the trail Clara and the child had carved. His face was blotched red, eyes glittering with fury, and when he spoke, it was with the booming authority of a man who had ruled through fear too long to surrender it easily.

“You think kneeling tricks and children’s tears will hold this town together?” he thundered, sweeping his arm toward the five Comanche brothers still crouched around the girl. “They come here with no land, no law, and you cheer them while they shame you. You forget who feeds you, who lent you seed when your fields were dry, who kept your barns from the auction block. You cross me now, and I will see every debt collected, every crop seized, every roof torn down for timber. I will leave Dust Haven nothing but ashes and beggars if you turn against me.”

His words struck like a lash of their own, faces paling across the square as men and women remembered the ledgers signed in desperation, the coin they owed that bound them tighter than rope. Some lowered their eyes, the weight of his grip pulling them back into silence, fear curling around their spines like smoke.

Norah, hearing from the loft where Gabriel had half-carried her to the window, felt her chest ache worse than the lashes. She saw shoulders slump, hands drop, hope wither. The mayor smiled at that flicker of fear, feeding on it like kindling. “Do you want your children starving?” he pressed. “Do you want to see your farms stripped bare because you chose a bleeding orphan and five strangers over the man who built this town?”

Murmurs rippled. Some turned away, unwilling to meet Clara’s eyes, unwilling to meet the girl’s. Gabriel glanced at Norah, her lips white with pain, but her eyes steady. “This is how he wins,” she rasped. “Not with guns, not with whips, but with hunger.”

Elias stepped forward then, his voice low but carrying like thunder over the plains. “No man builds a town by chaining its children and bleeding its widows. If Dust Haven has survived, it is because its people worked, sweated, buried, and rose again. He only took.”

His words steadied some, but the mayor laughed sharp as a knife. “Bold words from a man whose kind raided cattle in the night.” The insult was meant to split them further, to poison the fragile unity blooming in the square.

Raphael, the third brother, rose slowly, dust streaking his trousers and spread his arms wide, showing his empty hands. “We carry no rifles. We came because she carried pain, not hers. If that is savagery, then perhaps savagery is the only honor left.”

The crowd stirred. Shame prickled some, anger at the mayor stirring others, but the threat of debt—of barns seized—still clung heavy. Norah pressed her hand to the window frame, her body trembling, and called down with the last strength in her throat, her voice breaking but fierce enough to cut through. “He says he built you, but you built yourselves. He says he owns your bread. But bread baked by your own hands fed me when I had nothing. He cannot starve what you refuse to surrender.”

The words cracked something small but real. A murmur swelling through the crowd as men and women looked at their own hands, at the earth beneath their boots, at the truth they had buried under fear.

The mayor saw it, and his smile faltered, rage twisting his features as he spat, “You’ll regret this. By sundown, Dust Haven will remember who owns it.” He turned sharply, signaling to a pair of riders lurking at the edge of town, and the square felt the air shift. The threat of violence drawing close like storm clouds on the horizon.

The mayor’s signal had barely flicked before two riders spurred their horses forward, dust boiling up behind them as they circled the square like wolves around sheep. Rifles slung low and eyes hard with the promise of violence. Townsfolk scattered from their path, skirts and hats snatched by the wind, while the mayor folded his arms smugly, certain fear would do what his words had not.

“See,” he crowed, his voice cutting through the commotion. “One shout from me, and you scatter like hens. You dare defy the man who keeps the riders fed?”

The horses clattered past the livery, rattling its doors. From the loft window, Norah pressed against the frame, her back a flame, her heart seizing as she saw mothers pull children from the street. Men who had moments ago stood tall now ducked behind barrels, every face bowing to fear again.

Elias motioned to his brothers, calm and steady. “Stay low,” he murmured, though his eyes never left the riders. Matteo’s knife gleamed at his belt. Raphael’s hand tightened on the beam. Thomas flexed his shoulders. Gabriel glanced once at Norah before stepping into the open, his rawhide crown still dangling from his hand.

“Fool!” one of the horsemen spat, yanking his rein so close the animal’s breath steamed over Gabriel’s face. “Move or you’ll be trampled.” But Gabriel stood still, his voice level. “If you want them to kneel, you’ll ride me down first.”

The words cracked over the square louder than a rifle. Elias and the other brothers joined him, forming a wall of flesh and will, unarmed but unflinching. The crowd held its breath as the riders reared their mounts, hooves striking sparks from the stones.

At the loft window, Norah felt despair claw her chest until the small Comanche girl, the one she had saved, slipped from Clara’s grasp and ran straight into the square. She darted between the brothers, planting her thin body before Gabriel, her voice ringing high and sharp. “No child alone.”

The vow leapt from her lips like fire, and in its echo, a murmur spread. Men whispering it to themselves, women clutching children and repeating it. Clara said it aloud, then the blacksmith, then three ranchers at once, until the whole square rolled with the words, a chant rising against the mayor’s roar. “No child alone! No child alone!”

The riders faltered, their mounts stamping uneasily at the sound. The brothers dropped to their knees as one, surrounding the girl, open palms raised, honoring her courage the same way they had honored Norah. The crowd gasped, the sight burning into their eyes—five warriors kneeling not in defeat, but in chosen humility, declaring before God and town alike that honor did not ride rifles; it knelt with the weak.

The chant swelled, rattling the windows, drowning the mayor’s fury. “No child alone!” Norah, trembling at the window, felt tears sting her lashes as she whispered it too, her voice raw but alive. For the first time, the fear that had ruled Dust Haven wavered, cracked open by one small voice echoed by a hundred more.

And the riders, men paid in threats and coin, looked at each other and found no command in their reins. The chant still shook the air when the mayor shoved through the crowd, his face twisted with the fury of a man watching his grip slip grain by grain through clenched fists.

“Enough!” he bellowed, his voice cracking, but the words, “No child alone,” rolled right over him like thunder across the plains. The riders pulled their horses back, uneasy, their eyes darting to the townsfolk who no longer cowered but shouted louder—fists pounding against wagon rails, women raising their children high as if to prove they had nothing left to fear.

The mayor’s jaw clenched. He needed a harder weapon than words. He thrust his hand into his coat and yanked out a folded ledger, the pages creased and heavy with ink. He held it high so the sun struck the wax seal, his voice dripping venom as he shouted, “You think honor feeds you? You think chance paid debts? Every name in this book owes me. Every one of you lives by my hand. Barns, cattle, seed, tools. It is all mine until your debts are cleared. And if you follow her, if you side with these savages, I will call them all due tonight. Every acre will be mine, every crib emptied, every roof torn down to repay what you owe.”

The chant faltered, voices thinning under the weight of old fear. In its ink lay the truth of how he’d bound the town for years, turning hunger into chains no knife could cut. He slammed it against his palm for emphasis, the sound sharp as the crack of the lash.

“This is your law. She shamed you. They mocked you. And now you’ll pay me every last grain or crawl on your bellies.”

At that, Norah’s voice cracked the air, hoarse but fierce. “You own nothing but fear.” She leaned hard against the frame, her wounds screaming, but her words carried. “This book is not law. It is a list of theft. If you bow to it, you bow forever. But if you burn it, he is nothing.”

The crowd gasped at the word burn. The mayor’s smile faltered, clutching the ledger tighter, his knuckles white. The brothers rose slowly, Elias’s voice rumbling like distant thunder. “Then let Dust Haven decide what it kneels to: ink or honor.”

The townsfolk shifted, breaths thick. And then slowly men and women began to kneel—not to the mayor, not to law, but in a circle around Norah, who leaned on the loft window, tears streaking her dust-stained face. They knelt for the orphan who had bled for a child that wasn’t hers, who had chosen humanity.

When silence was safer, the Comanche brothers rose as one, lifting Norah’s torn apron Clara had carried into the square. Elias held it high, still stiff with blood, then laid it across her shoulders with reverence, as though crowning her not with fabric, but with truth itself.

Gabriel stepped into the center, finally setting the braided crown upon her head, his words ringing steady: “She carried our pain. Now we carry her honor.”

The people murmured assent, some weeping, some holding their children close. A town unshackled, not by law or coin, but by a shared vow that had risen from one act of sacrifice.

The mayor sagged to the dust, bound and shaking, no voice left to wield. Dust Haven had chosen its verdict, and it was not written in his ink, but in the blood and courage of a woman they could no longer ignore.

The night after the ledger turned to ash, Dust Haven did not sleep. Lamps burned in windows, voices carried low but steady. Neighbors who had once eyed each other with suspicion now spoke of seed to share, fences to mend, bread to divide.

In the loft above the livery, Norah lay swaddled in quilts stitched by hands that once ignored her, her back raw but tended with poultices, her fever cooled by the Comanche brothers who kept watch in shifts. The young native girl she had saved nestled at her side, fingers curled around Norah’s bandaged hand, as if refusing to let her slip away.

When dawn’s first light cut across the plains, the brothers gathered with her. Gabriel, kneeling to set the simple rawhide crown gently on her brow again, while Elias spoke in his deep rumble: “You bled for one who was not yours. Today you belong to all of us.”

She tried to protest, whispering hoarsely, “I’m no leader, no saint. I was just an orphan who couldn’t stand still.”

But Raphael shook his head, laying a hand over hers. “That is why you belong. Only those who know hunger share bread freely.”

Below, the townsfolk had gathered in the square, not with jeers, but with baskets, apples, loaves, bolts of cloth, jars of milk. Each offering laid at the livery doors, small tokens of gratitude to a woman who had once been invisible to them.

Clara Jenkins wiped her eyes, whispering, “No child alone.” And the words spread, whispered back until it rose as softly as the morning wind, a vow remade in dozens of voices.

The mayor sat bound in the jailhouse, powerless. His reign ended not by bullet, but by conscience. His threats echoed no further than the iron bars that caged him.

By mid-morning, the brothers led Norah into the sunlight, slow and steady, the crowd parting without command. Mothers bowed their heads, children clutched their hands, men removed their hats. Gabriel carried the rawhide crown in both hands until he reached the center of the square.

Then he placed it back on Norah’s brow and stepped away. One by one, the brothers knelt, palms open, not as warriors demanding respect, but as men giving it. Then something no one expected happened. The crowd followed, men dropped to knees, women bowed low, children mirrored them—not to worship, but to honor a vow made flesh.

Norah, trembling under the weight of it, felt tears burn her eyes. She tried to speak, but her voice broke, and so she only whispered the words back to them, her lips quivering. “No child alone.”

A hush settled, thick and alive. The youngest child in the crowd repeated it, then another, until it became a chorus, a prayer not tied to church or law, but to humanity itself.

The brothers rose then, not with ceremony, but with the quiet dignity of men who had kept their vow. Elias clasped Norah’s hand once, his eyes steady. “You are their keeper now,” he said.

And with that, the five turned toward their horses, leaving the town to carry its own fire. As their silhouettes faded against the horizon, Norah stood crowned in rawhide, the Comanche child at her side, the townsfolk arrayed around her like a circle of guardians.

The sun rose higher, spilling gold across roofs and faces, and Dust Haven, for the first time in years, looked less like a place of fear and more like a home. And in that light, where scars burned but did not break her, Norah finally understood.

She had not been crowned with leather, but with the weight of honor itself—an honor built not on blood or tribe or law, but on the simple vow of humanity that would outlive them all.

Please like, share, and subscribe to support more truehearted stories left behind. If you had stood in Dust Haven that day, would you have knelt with the brothers, too?

.

play video: