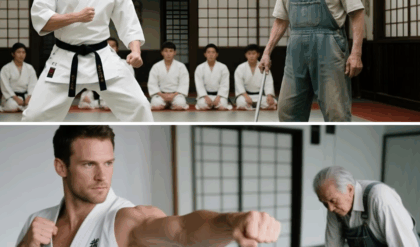

She Found a Lakota Warrior Dying in the Snow—Three Days Later, His Tribe Surrounded Her Cabin

.

.

.She Found a Lakota Warrior Dying in the Snow—Three Days Later, His Tribe Surrounded Her Cabin

The Dakota Territory, 1878. Winter had come with a vengeance, clawing at the land with icy teeth. The blizzards that swept through the Paha Sapa—the sacred Black Hills—were relentless, transforming the familiar contours of the wilderness into a monochrome world of white and gray. Elara Vance, a woman who had come seeking solitude, found herself more isolated than ever in her small cabin nestled deep in the folds of the hills. She had built this cabin with her late husband Daniel, its sturdy log walls a bulwark against the elements. Daniel had been gone three years now, claimed by lung fever, and the silence of the wild had become Elara’s closest companion.

Elara was an outsider—a white woman in a land that had belonged to the Lakota for countless generations. She respected the boundaries, never venturing too far, never taking more than she needed. Relations between settlers and the Lakota were tense, held together by fragile treaties and uneasy truces. Elara kept to herself, surviving on dried meats, preserved berries, and flour, always mindful that she was a guest in this ancient place.

When the blizzard raged for two days, Elara’s concern was not for herself but for the creatures caught in the storm’s grip. On the third morning, as the wind lessened to a mournful sigh and snow still fell thick and heavy, Elara scraped a patch of frost from her window and peered out. The world was silent, blanketed in white. It was then she saw it—a smudge of darkness near the edge of the clearing, where the forest began to reclaim the land. At first, she thought it was a fallen branch, but as the light shifted, the shape resolved itself with horrifying clarity. It was a man. Or what was left of one.

Fear pierced her. This was Lakota territory. A lone white woman and a dying Indian warrior at her doorstep was a recipe for disaster. Memories of recent conflicts, broken treaties, and bloodshed haunted both peoples. But Daniel’s voice echoed in her mind: “Every soul’s worth saving, Elara, if you’ve the means.” She hesitated, then pulled on her thickest mittens, wrapped a scarf around her head, and took down Daniel’s old hunting rifle—not for aggression, but for protection.

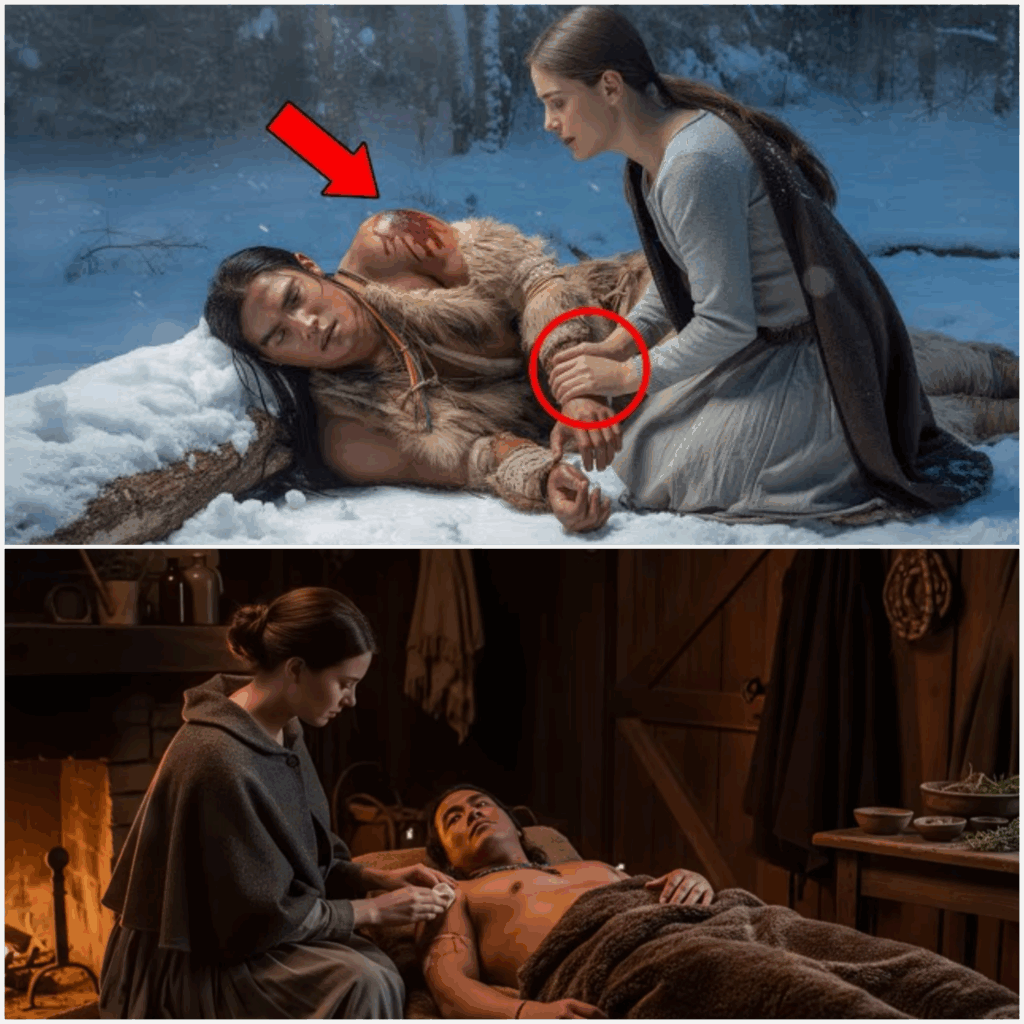

The snow was hip-deep, each step a lung-burning effort. As she drew closer, the details became clearer. The man was Lakota, his heritage proclaimed by beaded leggings and a buffalo hide tunic now soaked and frozen. His dark hair was matted with ice, fanned out around a face that was ashen, almost blue. He lay sprawled on his stomach, one arm outstretched, the other curled beneath him. A decorated bow lay splintered nearby, and a quiver of arrows was strapped to his back. There was no horse in sight.

Elara knelt, laying the rifle beside her. She touched his neck, searching for a pulse. It was there—thready and faint, a fragile flutter against the icy grip of death. His breathing was shallow, almost imperceptible. He was young, perhaps no more than twenty-five winters, a warrior in his prime struck down by the storm or something more sinister. She found no visible wound at first, but the way he was curled suggested pain beyond just the cold.

He was dying. If she left him, he would be dead before noon. Bringing him into her cabin was an enormous risk. What if he woke violent? What if his people found him there? Yet to leave him to the snow felt like a betrayal of her own humanity. With a grunt, Elara set about the herculean task of dragging him to her cabin, using her shawl as a makeshift sling. Inch by painstaking inch, she pulled him through the snow, her breath rasping in her chest, muscles screaming, cold seeping into her bones.

Inside, the relative warmth was a shock. She managed to drag him onto the rug before the hearth, collapsing beside him. The fire had dwindled to embers, and the room was chilling fast. Her first priority was to revive the flames. With trembling hands, she coaxed the fire back to life, then turned her attention to the Lakota warrior. As the heat built, chasing the deadly chill from his limbs, he remained terrifyingly still, his skin like frosted marble.

She had to get him out of his frozen clothes. It was a violation—touching an unknown man, a man from a people often portrayed as enemies. But his life depended on it. She carefully cut away the stiff, icy tunic and leggings, revealing shockingly cold skin. She covered him with her thickest blankets, heated water, and began to gently chafe his hands and feet, trying to restore circulation.

As she eased his position, she found the source of his incapacitation: the fletching of an arrow, its shaft broken off, leaving the arrowhead embedded deep in his right side below the ribs. The surrounding buckskin was stiff with frozen blood. He hadn’t just been caught in the storm—he’d been shot. Ambushed by whom? Rival warriors? White men? The possibilities were grim.

Her knowledge of medicine was rudimentary, learned from her mother and supplemented by necessity. She knew how to treat fevers, set simple fractures, and stitch wounds, but an arrow lodged near vital organs was beyond her experience. To leave it in invited infection and slow death; to remove it risked uncontrollable bleeding.

He groaned, a low guttural sound, and his eyelids fluttered. Dark eyes, unfocused and clouded with pain, stared at the ceiling. He muttered something in Lakota, words rough and strained. “Easy now,” she whispered. “You’re safe. For now.” She knew she had to try to remove the arrowhead. She sterilized Daniel’s knife in the flames, her heart hammering. She cut away the buckskin around the wound, the flesh torn and swollen. The broken shaft was buried deep.

He cried out, his body arching even in its weakened state. “I’m sorry,” she breathed, tears pricking her eyes. “I have to.” She needed him more aware, to know if the arrowhead was barbed. He lapsed back into unconsciousness. For the rest of the day and into the night, she focused on warming him, forcing sips of broth between his cracked lips, cleaning the wound as best she could, packing it with yarrow to staunch bleeding and fight infection.

The second day dawned with no break in the snow, though the wind had died. The silence was profound. He drifted in and out of consciousness, sometimes staring at her with confusion, perhaps a touch of fear. She spoke softly, telling him he was safe, hoping her tone would convey her intent. She found a small leather pouch tied to his belt—inside, dried meat, a flint, and a carved bone wolf. It felt deeply personal. She noted the fine beadwork on his moccasins and quiver. He was a man of standing, or from a family that cared deeply.

Late in the afternoon, his fever climbed. He thrashed weakly, muttering deliriously. She bathed his forehead, changed the poultice, dribbled more broth and water into his mouth. The arrow was a ticking clock. Infection was setting in. She had to decide: try to pull it, or ride for help? The nearest settlement was Deadwood, a two-day ride in good weather—impossible now.

That night, as she spooned deer broth between his lips, his eyes opened with a spark of recognition. He focused on her face, whispered “Thahaya. Enemy.” She put her hand on her chest. “Elara,” she said, then pointed to him. “Friend. Cola.” A flicker of surprise passed through his eyes. He tried to speak again but was wracked by pain. “The arrow,” she said, miming barbs. He shook his head, barely perceptible.

The morning of the third day arrived. The snow had stopped, the sky a hard bright blue. This was her last chance. She built up the fire, boiled water, laid out clean rags and the knife. “I am going to try and take it out now,” she told him. He watched her, lucid despite the fever. She knelt beside him, stomach churning, offered a silent prayer, and grasped the broken shaft.

A roar of pain tore through the cabin as she pulled. Blood welled instantly. Panic seized her, but she pressed the yarrow poultice against the wound, applying pressure. He went limp, mercifully unconscious. The bleeding subsided. She cleaned the wound, bound it tightly with strips of linen. The arrowhead was obsidian, finely crafted—not Army, not Crow. Another mystery.

As dusk fell, Elara heard hoofbeats outside—many. She scraped frost from the window. A semicircle of at least fifteen Lakota warriors surrounded her cabin, their faces grim, impassive. At their forefront was a man who radiated authority—older, scarred, his eyes sharp. He pointed to the cabin, then made a questioning gesture. Elara nodded. “He is here. Cola. Friend.” She tapped her chest. “Elara. Cola.”

He spoke, pointing to himself. “Matau,” then gestured to the cabin. “Wanacha. My younger brother.” Relief and dread mingled in Elara’s heart. The warriors entered, checking on Wanacha, speaking in low Lakota. The tension eased a fraction. Matau examined the arrowhead, recognized its craftsmanship, grunted approval. “Washday. Good.”

But the danger was not over. Suddenly, more figures appeared at the edge of the clearing—white men, four of them, rifles in hand. Prospectors, but with a hardness that chilled Elara. Matau issued rapid commands. The Lakota melted into the trees, readying for battle. He pointed to Daniel’s rifle, then to Elara—a question, an acknowledgment of her role. She picked up the rifle, hands steady.

The white men approached. “Hello the cabin! Anybody home?” Their voices were rough, greedy. Wanacha let out a sudden Lakota war cry—a warning. Gunfire erupted. The fight was short, brutal. Elara fired, wounding the red-bearded leader. The Lakota overwhelmed the ambushers. Silence descended, broken only by groans and victorious shouts.

Matau approached Elara, his eyes now filled with raw respect. “White woman. Her spirit is strong. Great.” He handed her a beaded leather pouch—a gift of thanks. Wanacha, propped against the wall, managed a weak smile. The Lakota prepared to depart, lifting Wanacha onto a travois.

Before leaving, Matau looked at Elara. “You would have done the same for your kin,” she said softly. He nodded, a profound acknowledgment. The Lakota melted into the forest, leaving Elara standing alone in the bloodstained snow.

The silence that returned was different now—not isolation, but aftermath. Elara looked at the pouch, then at the wilderness. She had found a dying Lakota warrior in the snow; three days later, his tribe had surrounded her cabin. In the heart of that confrontation, a bridge—however fragile—had been built between two worlds. The snows would melt, but the memory of Wanacha and his honorable brother Matau would remain etched in her soul. Elara Vance’s courage and compassion rewrote her story in the unforgiving landscape of the Wild West. She chose humanity over prejudice, forging an unexpected bond in a world defined by conflict. The Lakota left her with more than a gift—they left her with a testament to the strength of the human spirit, and the surprising paths to understanding that can be found even in the deepest snows of mistrust.

play video: